DEATH UNDER MAO

Great Leap Forward poster Scholars believe that Mao in some way was involved in the death of at least 40 million people and possibly as many as 80 million, more deaths during peace time than any other leader. Most of them perished during the Great Famine in the late 1950s, which followed the Great Leap Forward. Millions more may have died in the Cultural Revolution. In comparison, Hitler was responsible for 12 million concentration camps deaths and Stalin killed between 30 and 40 million during the purges and famines of the 1920s and 30s.

Responding to a comparison with him and China's brutal first emperor Qui Shi Huangdi Mao said in 1969, "What was so remarkable about Qin Shi Huangdi? He executed 460 scholars. We executed 46,000 of them!...You think you insult us by saying we are like Qin Shi Huangdi, but you make a mistake, we have passed him a hundred times!" [Sources: Simon Leys, Chinese Shadows]

“How many hard-working farmers died of starvation during the last 60 years? How many mistakes were made? How many good and honest people have died?” wrote Bao Tong, once a senior official and now a dissident. On the Chinese Communist Party destroying traditional values, Yang Jisheng, author an authoritative account of the Great Famine, told the New York Review of Books, “Traditional values involve valuing life, valuing others, not doing unto others what you don’t want done to yourself. All of these values were negated. From 1950 onward, the Communists criticized the passing down of traditional values. There was a moral vacuum.”

Some older Chinese say what they remember most about the Mao era was the pervasive feeling of fear. Harry Wu, a political prisoner for 19 years, estimates that 60 million people have been sentenced to "labor reform" since 1949. In the 1970s, U.S. government officials using satellite photographs and other information, estimated that between 2 million and 6 million Chinese were in prison at one time. Bases on an assumption that between 5 and 10 percent of all prisoners die while in prison, scholars conclude that perhaps 3 million to 6 million people died in Chinese prisons in the Mao era. [Source: Washington Post, July 17, 1994]

In the campaign to suppress counterrevolutionaries in the 1950s, 2.4 million people were executed according to official figures.How exactly to deal with China was a controversial topic in the 1950s and 60s. Nixon and Kennedy debated the issue during the 1960 presidential campaign.

Wang Shouxin Execution in 1980 Good Websites and Sources on the Great Leap Forward: University of Chicago Chronicle chronicle.uchicago.edu ; Wikipedia ; Industrial Planning Video You Tube ; Death Under Mao: Uncounted Millions, Washington Post article paulbogdanor.com ; Death Tolls erols.com ; Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao ; Mao Quotations art-bin.com; Marxist.org marxists.org ; New York Times topics.nytimes.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Tombstone" by Yang Jisheng, the first proper history of the Great Leap Forward and the famine of 1959 and 1961 Amazon.com;

"Mao's Great Famine: The History of China's Most Devastating Catastrophe, 1958-62" by Frank Dikotter (Walker & Co, 2010) Amazon.com; “Blood Letters: The Untold Story of Lin Zhao, a Martyr in Mao's China” by Lian Xi Amazon.com;

"Life and Death Are Wearing Me Out" by Mo Yan (Arcade,2008), s narrated by a series of animals that witnessed the Land Reform Movement and Great Leap Forward Amazon.com;

"The Tragedy of Liberation: A History of the Chinese Revolution, 1945-1957" by Frank Dikotter, describes the Anti-Rightist period. Amazon.com;

"China Witness, Voices from a Silent Generation" by Xinran (Pantheon Books, 2009) is collection of oral histories from Chinese who survived the Mao period Amazon.com

. "Fanshen" by William Hinton is the classic account of rural revolution during the communist-led civil war in the late 1940s Amazon.com;

"Mao; the Untold Story" by Jung Chang and Jon Halliday (Knopf. 2005) Amazon.com;

“Mao Zedong” by Jonathan Spence, Alexander Adams, et al. Amazon.com;

"The Private Life of Chairman Mao" by Dr. Li Zhisui (1994) Amazon.com;

“Mao Zedong: A Political and Intellectual Portrait” by Maurice Meisner Amazon.com;

"Mao's New World: Political Culture in the Early People's Republic" by Chang-tai Hung (Cornell University Press, 2011) Amazon.com;

“The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 14: The People's Republic, Part 1: The Emergence of Revolutionary China, 1949-1965" by Roderick MacFarquhar and John K. Fairbank Amazon.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION AND NIXON factsanddetails.com; REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; MAO'S PERSONALITY CULT, LEADERSHIP AND MAOIST PROPAGANDA factsanddetails.com MAO'S PRIVATE LIFE AND SEXUAL ACTIVITY factsanddetails.com; JIANG QING, LIN BIAO, ZHOU ENLAI factsanddetails.com; COMMUNISTS TAKE OVER CHINA factsanddetails.com; FAMOUS ESSAYS BY MAO ZEDONG AND OTHER CHINESE COMMUNISTS AS THEY TAKE POWER factsanddetails.com; EARLY COMMUNIST CHINA UNDER MAO factsanddetails.com; CHINA, THE KOREAN WAR, POWS, SPIES AND THE C.I.A. factsanddetails.com; CHINESE TAKEOVER OF TIBET IN THE 1950s factsanddetails.com; COMMUNES, LAND REFORM AND COLLECTIVISM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; DAILY LIFE IN MAOIST CHINA factsanddetails.com; BAREFOOT DOCTORS AND HEALTH CARE IN THE MAO ERA factsanddetails.com; HUNDRED FLOWERS CAMPAIGN AND THE ANTI-RIGHTIST MOVEMENT factsanddetails.com; GREAT LEAP FORWARD: MOBILIZING THE MASSES, BACKYARD FURNACES AND SUFFERING factsanddetails.com; GREAT FAMINE OF MAOIST-ERA CHINA: MASS STARVATION, GRAIN EXPORTS, MAYBE 45 MILLION DEAD factsanddetails.com; TOMBSTONE AND RESEARCH OF THE GREAT FAMINE factsanddetails.com; CHINESE REPRESSION IN TIBET IN THE LATE 1950s AND EARLY 1960s factsanddetails.com

Violence in the Early Years of the People's Republic

Wang Shouxin Execution

The first people to die after Mao came to power in 1949 were "landlords" killed by their fellow villagers during a land reform campaign in the 1950s. In an attempt to break down the power base of the landowners at least one landlord in every village was arrested by Communist security forces and tried in a "people's tribunal." Sinologists estimate that between 1 million and 4 million people were killed during the campaign.

“Zhang Meizhi is a widow of a former local official in southern China who was executed, along with Zhang's brother, in front of her during the 1952 Land Reform. She told Liao Yiwu in the book "The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up" that the the tongues of the two men were cut out for use in traditional medicine. Zhang was then locked up for forty days, during which time her 2-year-old daughter starved to death. As the persecution of these so-called rich peasants continued, Zhang's eldest son fled the village, taking refuge in an underground vegetable cellar next to a cultivated field, where he stayed in secret for two years. Eventually he was discovered, and a younger brother who fed him surreptitiously was shot dead by the police. The fugitive son was given a life sentence for antirevolutionary crimes, which was commuted only after thirty years in prison. “I grew up in a family with generations of educated people,” Zhang tells Liao. “We had a glorious family history. I used to keep a record of my family history. The Poor Peasants Revolutionary Committee dug it out and burned it. My house was so thoroughly searched that there was no place for a mouse to hide.” [Source: "The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up" by Liao Yiwu, from book review by Howard W. French in The Nation, August 4, 2008]

In 1953, Mao declared that "95 percent of the people are good," which lead to an attack against "counter-revolutionaries" and "bad elements" that made up the remaining 5 percent. Hundreds of thousands, and perhaps as many as a million, people were killed in a campaign against counter-revolutionaries, Kuomintang sympathizers, Christians and members of other religious groups.

Collectivism

In the early 1950s the Communists helped form mutual aid teams, the precursors to cooperatives. In 1955, Mao decreed that all farmers should "voluntarily" organize into large cooperatives. The cooperatives were overseen by party cadres and large portions of the output was turned over to the state.

Large centrally planned People’s Communes were established in the late 1950s. The Communists had hoped that collectivism would help the huge Chinese population feed itself, but collectivism did not increase agricultural production.

Within a short time it was clear this system wasn’t workable. Distribution was always a problem. Even during the Cultural Revolution when every able-bodied person in the country was put to the task of raising food, food rotted in the fields and people starved.

Scholar William McNeil once wrote: "The problem is the Chinese have never been able to organize collective effort with the sort of enthusiasm and efficiency of the Japanese. There is a kind of ruthless individualism in Chinese life, a competitiveness and acquisitiveness, that may make modern large-scale industrial organization difficult.”

Mao initially followed the Soviet model for collectivism but became impatient with the slow pace of development and turned to radical mass movements like the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Wang Shouxin Execution

Repression Under Mao

Jiabiangou was a notorious labor camp that operating in northwest China between 1957 and 1960 where people were sent simply for have a relative that once owned a business or served under Chaing Kai-shek. Some were turned in by their parents and siblings who wanted to save their own necks. Of the 3,000 prisoners that were sent there only 600 survived.

In her book "Woman from Shanghai", Yang Xianhuo tracked down 100 Jiabiangou survivors and recounted the stories of 13 of them in slightly fictionalized form to escape censorship by Chinese officials. The prisoners suffered extreme malnourishment and stole food and ate human and animal excrement to survive, “Hunger warped their brains,” Yang wrote, “When they woke up each morning, all they could think about was food.”

In her book "Life and Death in Shanghai" (1987), Nien Cheng described her six horrid years in prison, after being cast as a capitalist sympathizer because she worked for the oil company Shell, and the death of her daughter during the Cultural Revolution. In the book she describes how her interrogators forced her write a confession and then sign it with the words “signature of a criminal” printed along the bottom and how she infuriated them to the point they threatened to shoot her because she added the words “who did not commit any crime”. Nien told the Washington Post, “Maoists were essentially bullies. If I had allowed them to insult me at will, they would have been encouraged to go further.”

"Prisoner of Mao" by Bao Ruo-Wang is the story an innocent man trapped in a Chinese labor camp between 1957 and 1964.

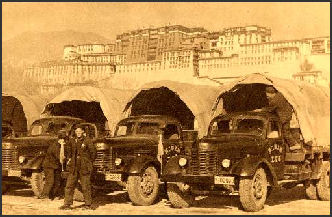

Two days after the Dalai Lama escaped from Lhasa, the Communists closed down the Tibetan government, seized land and bombed Potala palace, Sera Monastery and the medical college of Changp Ri. Chinese snipers picked off protestors, some with Molotov cocktails, in the streets. When more 10,000 protestor sought refuge in the Jokhang Temple, it too was bombed. By some estimated 10,000 to 15,000 Tibetans were killed in three days of violence.

Early Communist Persecution of Religion in China

Master Deng Kuan, abbot of the Gu Temple in Sichuan Province, was 103 when the writer Liao Yiwu met him in 2003. “Over the centuries, as olddynasties collapsed and new ones came into being, the temple remained relatively intact,” Deng told Lao, “This is because changes of dynasty or government were considered secular affairs. Monks like me didn't get involved. But the Communist revolution in 1949 was a turning point for me and the temple.”[Source: “ The Corpse Walker: Real-Life Stories, China From the Bottom Up “ by Liao Yiwu, from book review by Howard W. French in The Nation, August 4, 2008]

Wang Shouxin Execution

"Soon after Mao's victory, Deng was dragged out of his temple and stood up before a crowd, accused of accumulating wealth without engaging in physical labor, and spreading “feudalistic and religious ideas that poisoned people's minds.” People stepped forward to denounce him, and the crowd that gathered responded on cue, howling slogans like “Down with the evil landlord” and “Religion is spiritual poison.” Some spat on him. Others punched and kicked. “No matter which temple you go to, you will find the same rule: monks pass on the Buddhist treasures from one generation to the next,” Deng says. ‘since ancient times, no abbot, monk, or nun has ever claimed the properties of the temple as his or her own. Who would have thought that overnight all of us would be classified as rich landowners! None of us has ever lived the life of a rich landowner, but we certainly suffered the retribution accorded one.” [Ibid]

By Master Deng's reckoning, between 1952 and 1961 this meant he endured more than 300 ‘struggle sessions,” as these organized hazings were known in the revolution's euphemistic terminology. In his area of Sichuan Province, he tells Liao, by 1961 “half of the people labeled as members of the bad elements had starved to death.”

Enduring the Mao Era

Amy Qin wrote in the New York Times: Born in 1949, the year the People’s Republic was founded, Mr. Wang grew up in the eastern Chinese city of Hangzhou. The son of two high-ranking officials, he had, by his own account, a fortunate childhood. As a boy, he was selected to greet Premier Kim Il-sung of North Korea with flowers at the airport during an official visit. Soon after, the family’s fortunes took a turn. In 1959, when Mr. Wang was in elementary school, his father was sent to a labor camp as part of Mao’s campaign to purge counterrevolutionary intellectuals. [Source: Amy Qin, New York Times, August 19, 2017]

“That same year, Mr. Wang’s father was accused of being a “traitor of the Party” and killed himself. As the son of a traitor, Mr. Wang was blacklisted. In 1966, as Mao launched the campaign to destroy China’s “four olds” — ideas, customs, culture and habits — Mr. Wang was barred from his high school’s Red Guards, the paramilitary youth group that carried out the chairman’s purge. Because of his “bad family background,” Mr. Wang was denied jobs and, for years as a result, the opportunity to find a wife. “All the doors to love were completely closed to me, even my first crush,”

“By 1968, the Cultural Revolution was convulsing the country. Millions of young people were shipped from cities to the countryside to work on farms. In Hangzhou, Mr. Wang’s hometown, political struggles, demonstrations and house raids roiled the city. “To be honest, I really wanted to be part of it,” Mr. Wang wrote, but his family’s status kept him from participating in party activities. Instead, he and his peers became part of a lost generation, virtually written out of official histories that jump from the glories of independence to China’s ascension as an economic powerhouse. For me and my generational peers, this period of history is unforgettable, almost beyond belief,” Mr. Wang said in an interview. “Our entire youth was taken away. We didn’t fight a war, we didn’t learn anything, and when we came home, many of us couldn’t find jobs. We had nothing to show for ourselves.”

“When conflict broke out on the Soviet border in 1969, Mr. Wang saw an opportunity to pursue his dream of fighting for the People’s Liberation Army. He begged to join the military, and soon found himself in the northeastern province of Heilongjiang, leading a squad of men assigned to build tunnels. While the work was difficult, Mr. Wang’s platoon finished the tunnels, ahead of schedule, in the summer of 1970. By then, tensions with the Soviet Union had diminished and Mr. Wang’s company was dismissed.

“Unable to join the military as a regular soldier, Mr. Wang set his sights on becoming a photojournalist. He soon learned the blacklist extended to the nation’s newspapers as well. He was unable to find a job because of his father’s political history, and unable to find a girlfriend because he did not have a job. For fun, Mr. Wang and his friends — many of them also sons of purged officials — would drink baijiu, gamble and dress up for photos. As props, they used wine glasses and Western-style neckties, which Red Guards had confiscated during house raids of the bourgeoisie. Posing with the items was dangerous; even the slightest hint of capitalistic sympathies could invite trouble from the authorities. “We didn’t dare show them to anyone,” Mr. Wang said.

“In 1976, the last year of the Cultural Revolution, Mr. Wang finally found a job at the Zhejiang Provincial Museum, where his stepfather had worked. In 1981 he married, and in 1989 he made photography his full-time profession, becoming secretary general of the Hangzhou Photographers Association. For decades, he kept his photo collection in storage, hidden from public view. It was only when he retired in 2009 that he started thinking about publishing the photos. “I did it for the young Wang Qiuhang,” Mr. Wang said. “That Wang Qiuhang didn’t have a single penny in his pocket but he had film in his camera. And now his dream has finally been realized.”

Tibetan Revolt in 1959

On Tibetan New Year in 1959 a major Tibetan revolt occurred. To this day no one is sure how or why it began and how widespread it was. By most accounts, it started after the Dalai Lama was forced by the Chinese government to attend a performance of Chinese folk dance troupe during the holiday festivities. Rumors began spreading that the Tibetan leader was going to attend without his usual phalanx of 25 bodyguards and that the Chinese planned to kidnap him.

Large crowds that had assembled anyway for holidays gathered around Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s summer palace, and vowed to protect the Tibetan leader with their lives. The Dalai Lama had no choice but to cancel his appearance. The Chinese responded by declaring its 17-point agreement with Tibet was invalid. In an effort to head off violence, the Dalai Lama offered to turn himself over to the Chinese. The Chinese responded by firing two mortar shells into Norbulingka,.

The Dalai Lama decided it was time go. On the night of March 17, after mortar shells had exploded in the palace ground, the Dalai Lama disguised himself as a soldier, and flung a gun of his shoulder and fled Lhasa with 52 monks in similar disguises. His golden robe was left on a couch at Potala Palace awaiting his return.

The Dalai Lama fled to India. He traveled most of the distance on a brown horse with richly embroidered saddlebags. After crossing the Kyichi River in skin coracles, the Dalai Lama and his group traveled down the Tsangpo River (Brahmaputra) as far as it would take them and then traveled by horseback and on foot on trails through the Himalayas. The journey almost killed the Dalai Lama. He endured thunderstorms, long stretches without water and a dangerous blizzard at Lagoe Pass. "We had to cross high passes," the Dalai Lama wrote. "By the time we reached the border, we were exhausted and sick with fever and dysentery."

Hardships in the Early Mao Era

Liao Yiwu wrote in the NY Review of Books: “Before the Tiananmen massacre, my father told me: “Son, be good and stay at home, never provoke the Communist Party.” My father knew what he was talking about. His courage had been broken, by countless political campaigns. Right after the 1949 “liberation,” in his hometown Yanting [in Sichuan] they executed dozens of “despotic landowners” in a few minutes. That wasn’t enough fun for some people. They came with swords, severed those broken skulls, and kicked them down the river bank. And so the heads were floating away two or three at a time, just like time, or like the setting sun always waiting for fresh heads at the next ferry point. My father left my grandfather, who had made money through hard work, and fled in the night. [Source: Liao Yiwu, NY Review of Books, June 3, 2014, Translated by Martin Winter ***]

“Afterward he never said a bad word about the Communist Party. Even at the time of the Great Leap famine, when almost forty million people starved to death, and when I, his little son, almost died. He did not say anything. It was hell on earth. People ate grass and bark. They ate some kind of stinking clay; it was called Guanyin Soil [after the Buddhist Goddess of Mercy]. If they were very lucky, they would catch an earthworm; that was a rare delicacy. Many people died bloated from Guanyin Soil. ***

“My grandmother also died; she was just skin and bones. Grandfather carried her under his arm to the next slope, dug a small pit, and buried her. But Mao Zedong, the great deliverer of the Chinese people, would never admit a mistake. He just said it was the fault of the Soviet Union. And so the wretched people all hated the Soviet Union. Just because of their goddamned Revisionism [the label Chinese Communists used for Soviet ideology after the Sino-Soviet split in the early 1960s], the Soviets had called back their experts and their aid for China! Mao’s second-in-command Liu Shaoqi couldn’t stand it any longer and mumbled, “So many people have starved to death. History will record this.” For this slip he paid dearly. During the Cultural Revolution they let him starve to death in a secret prison. We have a saying: “Illness enters at the mouth, peril comes out at the mouth.”

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; Photpgraphs, Ohio State University except Tibet picture, Cosmic Unity; Wang Shouxin execution photos Northwestsouthwest.com ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2021