CULTURAL REVOLUTION CULTURE

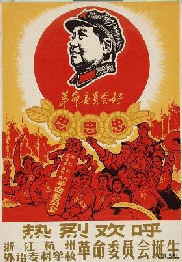

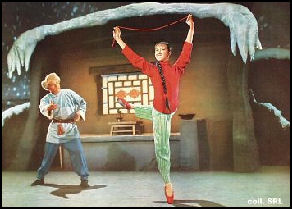

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Jiang Qing, Mao's wife, dominated cultural productions during the Cultural Revolution, The ideas she espoused through eight "Model Operas" were applied to all areas of the arts. These operas were performed continuously, and attendance was mandatory. Proletarian heroes and heroines were the main characters in each. The opera "The Red Women's Army" was a story about women from south China being organized to fight for a new and equal China. Ballet shoes and postures were used.

Jiang Qing emphasized "Three Stresses" as the guiding principle behind these operas.

[Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Jiang Qing, Mao's wife, dominated cultural productions during the Cultural Revolution, The ideas she espoused through eight "Model Operas" were applied to all areas of the arts. These operas were performed continuously, and attendance was mandatory. Proletarian heroes and heroines were the main characters in each. The opera "The Red Women's Army" was a story about women from south China being organized to fight for a new and equal China. Ballet shoes and postures were used.

Jiang Qing emphasized "Three Stresses" as the guiding principle behind these operas.

[Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

Denise Y. Ho told the Los Angeles Review of Books: “In the past, Cultural Revolution culture has been easy to dismiss. Despite Western fascination will objects that we might call “Mao kitsch” — buttons, statues, and posters — and Chinese nostalgia for Cultural Revolution music or plays, we have written off these cultural products as “just propaganda,” or not really culture at all. Recent scholarship has tried to change this view. One historian has suggested that the Communist Party created its own political culture, and that this was a key source of its legitimacy. Others have examined the art and music to show how Cultural Revolution culture was a modernization of both Chinese and Western traditions, part of a much longer project. Still others have focused on audience reception of these works, which could produce meanings beyond their propaganda messages. [Source: “Conversation with Denise Ho, Fabio Lanza, Yiching Wu, and Daniel Leese on the Cultural Revolution” by Alexander C. Cook,Los Angeles Review of Books, March 2, 2016 ~]

“My own research offers an illustration. I examine the use of exhibitions as part of political campaigns conducted before, during, and after the Cultural Revolution. I show that exhibits were a political and cultural practice that taught people how to make revolution. For example, during one campaign in the years before the Cultural Revolution, officials displayed individuals’ personal possessions along with posterboards explaining why they were political enemies. Then, when the Cultural Revolution broke out, Red Guards invaded people’s homes and confiscated their belongings, putting objects on display along with posters describing their crimes. So political culture provided ordinary people with a repertoire, with an idea of how to act and how to describe their actions. This kind of evidence helps us understand where the Cultural Revolution came from, and how such propaganda was deeply powerful — sometimes producing tragic consequences.” ~

Yiching Wu said: “This issue of how ordinary people were provided with political repertoires to be acted on helps account for the characteristically dispersed and explosive character of the Cultural Revolution. While the rebels looked to the Maoist leadership for political guidance, the relationships between Mao and those who responded to his call were tenuous and fragile. With the breakdown of the party hierarchy, political messages transmitted from above were interpreted in different ways by different agents. People responded to their own immediate circumstances, giving expression to a myriad of social grievances and antagonisms. The forces unleashed by Mao took on lives of their own.” ~

During the Cultural Revolution “vital and numerous love songs came under heavy fire” due to the suppression of folksongs devoid of overt politcal content. A major propaganda campaign was launched in 1973, which mobilized the masses against such widely ranging objects of attack as Lin Biao, the teachings of Confucius, and cultural exchanges with the West. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

During the Cultural Revolution “vital and numerous love songs came under heavy fire” due to the suppression of folksongs devoid of overt politcal content. A major propaganda campaign was launched in 1973, which mobilized the masses against such widely ranging objects of attack as Lin Biao, the teachings of Confucius, and cultural exchanges with the West. [Source: Columbia Encyclopedia, 6th ed., Columbia University Press]

Good Websites and Sources on the Cultural Revolution Virtual Museum of the Cultural Revolution cnd.org ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Morning Sun morningsun.org ; Red Guards and Cannibals New York Times ; The South China Morning Post 's multimedia report on the Cultural Revolution. multimedia.scmp.com. Cultural Revolution posters huntingtonarchive.org Great Leap Forward: University of Chicago Chronicle chronicle.uchicago.edu ; Mt. Holyoke China Essay Series mtholyoke.edu ; Wikipedia ; Industrial Planning Video You Tube ; Death Under Mao: Uncounted Millions, Washington Post article paulbogdanor.com ; Death Tolls erols.com ; Communist Party History Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Illustrated History of Communist Party china.org.cn ; Posters Landsberger Communist China Posters ; People’s Republic of China: Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; China Essay Series mtholyoke.edu ; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org; Mao Zedong Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; Mao Internet Library marx2mao.com ; Paul Noll Mao site paulnoll.com/China/Mao ; Mao Quotations art-bin.com; Marxist.org marxists.org ; New York Times topics.nytimes.com

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: CULTURAL REVOLUTION FILM AND BOOKS factsanddetails.com REPRESSION UNDER MAO, THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; REPUBLICAN CHINA, MAO AND THE EARLY COMMUNIST PERIOD factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: CAUSES, COSTS, BACKGROUND HISTORY AND FORCES BEHIND IT factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; RED GUARDS — ENFORCERS OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION — AND VIOLENCE ASSOCIATED WITH THEM factsanddetails.com; SURVIVING AND LIVING THROUGH THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION: DEATH TOLL, FIGHTING AND MASS KILLING factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com; BACK TO THE COUNTRYSIDE MOVEMENT OF THE CULTURAL REVOLUTION factsanddetails.com; CULTURAL REVOLUTION NOSTALGIA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Culture During the Cultural Revolution “Mao Cult: Rhetoric and Ritual in China's Cultural Revolution” Illustrated Edition by Daniel Leese Amazon.com; “Cultural Revolution and Revolutionary Culture” by Alessandro Russo Amazon.com; “Music as Mao's Weapon: Remembering the Cultural Revolution” by Lei X. Ouyang Amazon.com; “Listening to China’s Cultural Revolution: Music, Politics, and Cultural Continuities” by Laikwan Pang , Paul Clark, et al. Amazon.com; “Staging Revolution: Artistry and Aesthetics in Model Beijing Opera during the Cultural Revolution” by “Xing Fan Amazon.com; Revolutionary Bodies: Chinese Dance and the Socialist Legacy” by “Emily Wilcox Amazon.com; “A Continuous Revolution: Making Sense of Cultural Revolution Culture” by Barbara Mittler Amazon.com; “Maoist Model Theatre: The Semiotics of Gender and Sexuality in the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976)” by Rosemary A. Roberts Amazon.com; “Red Detachment of Women: A Modern Revolutionary Dance Drama” Amazon.com “Taking Tiger Mountain by strategy;: A modern revolutionary Peking opera” Amazon.com “The Little Red Book; Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung:” by Mao Tse-Tung Amazon.com About The Cultural Revolution “The World Turned Upside Down: a History of the Chinese Cultural Revolution” by Yang Jisheng (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2020 Amazon.com; "The Cultural Revolution: A People's History” by Frank Dikotter (Bloomsbury 2016) Amazon.com; “Red Color News Soldier: A Chinese Photographer’s Odyssey Through the Cultural Revolution,” by Li Zhensheng Amazon.com; “Enemies of the People” by Anne F. Thurston Amazon.com; Red Guards "My Name is Number 4: A True Story of the Cultural Revolution" by Ting-Xing Ye (Thomas Dunne, 2008) Amazon.com; “Confessions of a Red Guard: A Memoir” by Liang Xiaosheng and Howard Goldblatt Amazon.com; “Fractured Rebellion: The Beijing Red Guard Movement” by Andrew G. Walder Amazon.com

Education During he Cultural Revolution

According to the Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations: The Cultural Revolution affected education more than any other sector of society. Schools were shut down in mid-1966 to give the student Red Guards the opportunity to "make revolution" on and off campus. The Cultural Revolution touched off purges within the educational establishment. Upper- and middle level bureaucrats throughout the system were removed from office, and virtually entire university faculties and staffs dispersed. Although many lower schools had begun to reopen during 1969, several universities remained closed through the early 1970s, as an estimated 10 million urban students were removed to the countryside to take part in labor campaigns. During this period and its aftermath, revolutionary ideology, and local conditions became the principal determinants of curriculum. A nine-year program of compulsory education (compressed from 12 years) was established for youths 7–15 years of age. [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: ““The Cultural Revolution further broke the power of the existing educational bureaucracy, the professional academics, and any party leaders who supported them. This represented a final abolition of the obstacles the Chinese intellectual establishment had always imposed against radical reform of the educational system as a whole. It ended the authority of education professionals, which led to a general lowering of academic standards, particularly in higher education. As a result of the experimentation in that area, the content of college curricula on the average was reduced by half. The policy of sending city youth to rural areas to be "re-educated by peasants" also produced many millions of dissatisfied young people who failed to adapt to the rural lifestyle. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

See Separate Article HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Revolutionary Enthusiasm in the Cultural Revolution

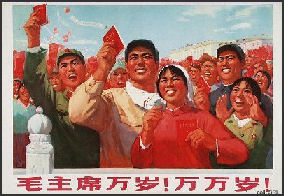

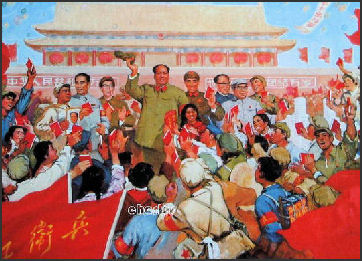

During the Cultural Revolution tens of millions of Chinese wore Mao badges churned out by an estimated 20,000 button-making factories. Men, women, boys and girls wore baggy Mao suits and ran around quoting sayings from "The Little Red Book". Chinese workers were regularly called upon to express their "boundless loyalty to Mao."

During the Cultural Revolution tens of millions of Chinese wore Mao badges churned out by an estimated 20,000 button-making factories. Men, women, boys and girls wore baggy Mao suits and ran around quoting sayings from "The Little Red Book". Chinese workers were regularly called upon to express their "boundless loyalty to Mao."

The photographer Li Zhensheng told the Los Angeles Times, “When Mao made his famous declaration to “destroy the old and establish the new” everyone was thrilled at the prospect of a revolution, including myself.” Born in in the old society but grown up under the Red Flag, “my generation was too young to have shared the excitement of the country’s founding in 1949. But now Chairman Mao said that we should have a revolution every seven or eight years, so I thought I could experience several of them during my lifetime.”

Zhensheng told the New York Times as time went on, “Things...were more and more foolish. Everyone was cold, and someone would shout, “Anybody cold? And we replied, “No, because we have a red sun in our hearts that is very warm.” Is the work difficult? Someone else would shout. “No, not at all,. It was far worse than this on the Long March.”

According to Chinese dissident Liu Binyan, "When Mao Zedong coined the slogan 'To rebel is justified,' everyone became a 'revolutionary' overnight...Mao ideology was pushed to such an extreme that chaos resulted. Both Mao's authority and ideology went bankrupt. The idealist illusions he had thrust upon the Chinese people turned to nihilism and cynicism." [Source: Newsweek, May 6, 1996]

During the Cultural Revolution, Mao ordered millions of urban people into the fields to help with the harvest; and millions more were conscripted to build railroads and dams. In Shanghai everyone was ordered to build bomb shelters in preparation "for the coming war." Today these shelters are used mainly as rendezvous for young lovers.

Consequences of Lack of Revolutionary Enthusiasm

The photographer Li Zhensheng told the Los Angeles Times, “Within several months...the true nature of the revolution revealed itself. Books were being burned, temples and churches sacked, and anyone not chanting with the crowd instantly became suspect. Despite the posters condemning 'counterrevolutionaries' and 'capitalists,' the main aim of the rallies was to humiliate and demean anyone with wealth, power or knowledge.”

Anyone perceived as not being sufficiently devoted to Mao and the revolution was persecuted. Club-wielding Red Guards beat to death thousands of people, including their friends, small children and babies for not being committed enough.

Slight offense against Mao or the revolution sometimes produced terrible consequences. In 1970, a 19-year-old student was sentenced to five years of prison and two more years of hard labor because he accidently used a picture of Chairman Mao to mop up some wine he accidently knocked over while he was drunk. He was arrested by a Communist official who trying to meet his quota of arresting class enemies. During his interrogation, handcuffs were clamped so tightly around his wrists that he still had scars 25 years later.

Cultural Revolution and the Arts

Mao’s wife Jiang was put in charge of the arts during the Cultural Revolution. She and her group of loyalist intellectuals and artists controlled everything: film studios, operas, theatrical companies and radio stations. They destroyed old movies and replaced them with new ones which were allowed to depict only eight revolution-related themes. Worker committees took over the studios and many administrators and actors were labeled as "devils and monsters" and dismissed and harangued. Even children's puppet theaters were closed down for being counter-revolutionary.

Mao’s wife Jiang was put in charge of the arts during the Cultural Revolution. She and her group of loyalist intellectuals and artists controlled everything: film studios, operas, theatrical companies and radio stations. They destroyed old movies and replaced them with new ones which were allowed to depict only eight revolution-related themes. Worker committees took over the studios and many administrators and actors were labeled as "devils and monsters" and dismissed and harangued. Even children's puppet theaters were closed down for being counter-revolutionary.

One of the objectives of the Cultural Revolution was to "socially purify" the arts.The popular play that many scholars say triggered the entire Cultural Revolution — "The Dismissal of Hai Rui from Office" — was a drama by historian Wu Han about an obscure Song dynasty official. The play was widely seen as as a traitorous critique of Mao's dismissal of Peng Dehuai, a military leader who criticized the Great Leap Forward.

Poets, artists and opera singers were imprisoned and exiled. Pop music was banned for being capitalist "poison" and Beijing Opera troupes were disbanded because they fit into the category of the "Four Olds." Among the banned writers were Aristotle, Plato, Shakespeare, Balzac, Jonathan Swift, Victor Hugo, Dickens and Mark Twain. Beethoven was banned until 1977.

Big Characters Posters (Dazibao) and Cultural Revolution Art

Big Characters Posters were used in the Cultural Revolution to publicize events, express views and carry out debates. It can be argued that the Cultural Revolution began with them. On May 25, 1966, according to Associated Press, "Big character" posters denouncing all those who would oppose Mao and his revolution begin appearing, opening the flood gates to mass political movements at college campuses throughout the country. Soon after, classes in schools nationwide are suspended indefinitely. \^

On an exhibition of such posters at Harvard, Michael Szonyi of Harvard’s Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies wrote: During the Cultural Revolution “big character posters” (dazibao ), were large, hand-written signs pasted on walls throughout China. Their content criticized local officials, colleagues, teachers, bosses, co-workers, former friends—virtually no one was exempt—for a wide-range of supposed political transgressions in what often became a cycle of high-stakes political attacks and counter-attacks.

“Despite the important role dazibao played in the visual and political landscape of the Cultural Revolution – as well as the subsequent Democracy Wall movement – they were never intended to be permanent, and so the vast majority were destroyed or simply decayed. Many China scholars, even experts on the period, have never had the chance to view dazibao up close. The creation of huge numbers of dazibao at this particular moment in China’s history can also be understood as an aesthetic or artistic phenomenon. Though only a scintilla of these works survive, dazibao occupy an important position in Chinese art history. Their reflection of the previous artistic tradition and their continuing inspiration for contemporary artists makes them perhaps as valuable to the art historian as to the student of politics.”

During the Cultural Revolution an attempt was made to replace Chinese characters with Latin alphabet because Cultural Revolution leaders believed that the old writing system "retards education and hampers communication." But many aspects of the Cultural Revolution simply defied logic. According to one saying, "a socialist train running late is better than a revisionist train running on time."

During the Cultural Revolution an attempt was made to replace Chinese characters with Latin alphabet because Cultural Revolution leaders believed that the old writing system "retards education and hampers communication." But many aspects of the Cultural Revolution simply defied logic. According to one saying, "a socialist train running late is better than a revisionist train running on time."

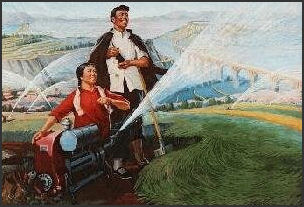

On 21 paintings dating from 1966 to 1976 at an exhibition in Chongqing called “100 Years of Chinese Art (1911-2011), The Art Newspaper reports: These depict officially sanctioned themes such as robust peasants and revolutionary figures portrayed in a stylised heroic style. The official requirements of the time were that art should be “hong, guang, liang” (red, bright, shiny) and “da, guang, qiang” (big, bright, powerful). “All artists were required to merge art and politics” while Mao was in power, says the exhibition’s curator Lu Peng, noting that before the Cultural Revolution there was still a degree of personal artistic expression within Mao’s restrictions. But the Cultural Revolution curtailed that diversity, he adds. [Source: The Art Newspaper, July 18, 2016]

“The decade was devastating for China; it did a lot of damage to Chinese art, and it had adverse impacts on the individual creations of artists,” writes Lu in the wall and catalogue texts accompanying the display. Although this may seem an understatement for the wholesale destruction of China’s historic sites, monuments and cultural artefacts by Mao’s student militias, the Red Guards, and the imprisonment, persecution and death of most of the country’s intellectuals, it is unusually rare to find such descriptions in public spaces and print publications in China. Often the Cultural Revolution is not even referred to by name and is described instead as “the decade”.

Cultural Revolution Literature

Man He of Williams College wrote: Liu Binyan’s “Between Man and Monster” (1979) is “a celebrated work of reportage that exposed corruption at a state-run coal-mining enterprise in Heilongjiang.” It “identifies misrule by monsters, not criminals, as the problem behind the Cultural Revolution. Wang Shouxin, the female official condemned in the work, is...emblematic of the “monsters” that ruled during the Cultural Revolution, [Source: Man He, Williams College, MCLC Resource Center Publication, July, 2017]

Dai Houying’s novel “Humanity, Ah Humanity!” (1980) is a literary testimony that “contested the conception of a rational, impersonal, and objectively existing force of justice”. He work has multiple narrators and prioritizes “psychological interiority over plot and emotions over hard facts. By reviving the genre of psychological realism, Dai probed her characters’ interiority, or more precisely their individual and emotional reactions to everyday alienation. Readers during the post-Mao transition were shown that “a truly just reckoning with the past must take full account of the complexity and individuality of human emotions”. The actualization of transitional justice did not merely rely on a story of requital; it was also rooted in the equation of “human circumstances” with “emotions”.

Yang Jiang’s 1981 memoir, “Six Records of a Cadre School” was a widely-read work and the “the first Cultural Revolution memoir by an established author.” It focuses on routine events that took place at a May Seventh Cadre School, a rural labor camp for sent-down urban intellectuals. Yang’s multiple, fragmented, and incomplete accounts reflect the complexities of the post-Mao transition.” Yang explores the :shame that exists among all who experienced the Cultural Revolution. She was assigned the job of guarding the collected feces of the cadre school from being stolen by local peasants.

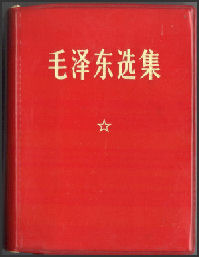

Little Red Book

The most widely read book in the Cultural Revolution and maybe the whole Mao period was "The Little Red Book" — actually titled "Mao's Selected Thoughts" — a collection of sayingsut together by Lin Biao in the Cultural Revolution. According to Time magazine, "No other book has had such a profound impact on so many people at the same time...If you read it enough it was supposed to change your brain.”

Some of the passages of the Little Red Book were set to music and slogans like "Reactionaries are Paper Tigers" and "We Should Support Whatever the Enemy Opposes"! were painted everywhere on billboards and walls.

The most widely read book in the Cultural Revolution and maybe the whole Mao period was "The Little Red Book" — actually titled "Mao's Selected Thoughts" — a collection of sayingsut together by Lin Biao in the Cultural Revolution. According to Time magazine, "No other book has had such a profound impact on so many people at the same time...If you read it enough it was supposed to change your brain.”

Some of the passages of the Little Red Book were set to music and slogans like "Reactionaries are Paper Tigers" and "We Should Support Whatever the Enemy Opposes"! were painted everywhere on billboards and walls.

John Gray of the New Statesman wrote: “Originally the book was conceived for internal use by the army. In 1961, the minister of defence Lin Biao – appointed by Mao after the previous holder of the post had been sacked for voicing criticism of the disastrous Great Leap Forward – instructed the army journal the PLA Daily to publish a daily quotation from Mao. Bringing together hundreds of excerpts from his published writings and speeches and presenting them under thematic rubrics, the first official edition was printed in 1964 by the general political department of the People’s Liberation Army in the water-resistant red vinyl design that would become iconic. [Source: John Gray, New Statesman, Cultural Capital Blog, May 24, 2014]

“By the time the Red Guard publication appeared, Mao’s Little Red Book had been published in numbers sufficient to supply a copy to every Chinese citizen in a population of more than 740 million. At the peak of its popularity from the mid-1960s to the mid-1970s, it was the most printed book in the world. In the years between 1966 and 1971, well over a billion copies of the official version were published and translations were issued in three dozen languages. There were many local reprints, illicit editions and unauthorised translations. Though exact figures are not possible, the text must count among the most widely distributed in all history.” In the view of historian Daniel Leese, the volume “ranks second only to the Bible” in terms of print circulation. \=\

Making Little Red Books

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, The book "was a keystone of Mao's personality cult. The population pored over it in daily study sessions; illiterate farmers memorised chunks by heart. In the west, translations were brandished by radicals. Many knew the text well enough to cite quotes by page number; they became ideological weapons to be wielded in any political struggle. Under siege by Red Guards, the then foreign minister reportedly retorted: "On page [X] it says Comrade Chen Yi is a good cadre …" But they also coloured even commonplace exchanges, as described by one historian: "Serve the people. Comrade, could I have two pounds of pork, please?" [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, September 27, 2013 ***]

“But the political frenzy ebbed, and production of the Little Red Book had mostly stopped long before Mao's death; afterwards, as China embarked on reform and opening up, officials began to pulp copies. Later, in a more relaxed age, commercial reprints and introductions to his thought appeared, but no new editions of his works: "This has been a very sensitive topic," said Daniel Leese, author of Mao Cult and an expert on the era at the University of Freiburg.” ***

Gray wrote: "It was not long before the Little Red Book and anyone connected with it fell out of favour with the Chinese authorities. In September 1971, Lin Biao – who had first promoted the use of Mao’s quotations in the army – died in a plane crash in circumstances that have never been properly explained. Condemned as distorting Mao’s ideas and exerting a “widespread and pernicious influence”, the book was withdrawn from circulation in February 1979 and a hundred million copies pulped.”

Little Red Book Sayings

The three main "Rules for Discipline" for soldiers and party workers in the Little Read Book were: "Obey orders in all your actions; Do not take a single needle or thread from the masses; and Turn in everything captured." Loyal Communists were also urged to "speak politely; return everything you borrow; don't swear at people; and do not take liberties with women."

On the topic of violence and revolution: 1) "Power grows out of the barrel of a gun." 2) "In order to get rid of the gun, it is necessary to take up the gun." 3) "Politics is war without bloodshed, while war is politics with bloodshed." 4) "When human society advances to the point where classes and states are eliminated, there will be no more wars." 5) “Fight no battle you are not sure of winning.”

Other famous sayings from the Little Red Book include, 1) "Modesty helps one go forward, whereas conceit makes one lag behind;" 2) "Investigation may be likened to the long months of pregnancy, and solving a problem to the day of birth. To investigate a problem is, indeed, to solve." And, 3) "People of the world, unite and defeat the U.S. aggressors and all the running dogs...Monsters of all kinds shall be destroyed."

Studying the Little Red Book

John Gray of the New Statesman wrote: “In 1968 a Red Guard publication instructed that scientists must follow Mao Zedong’s injunction: “Be resolute, fear no sacrifice and surmount every difficulty to win victory.” Expert knowledge was not valid, and might be dangerously misleading, without the great leader’s guidance. Examples of revolutionary science abounded at the time. In one account, a soldier training to be a veterinarian found it difficult to castrate pigs. Studying Mao’s words enabled him to overcome this selfish reaction and gave him courage to perform the task. In another inspirational tale, Mao’s thoughts inspired a new method of protecting their crops from bad weather: making rockets and shooting them into the sky, peasants were able to disperse the clouds and prevent hailstorms. [Source: John Gray, New Statesman, Cultural Capital Blog, May 24, 2014 \=]

“With its words intended to be recited in groups, the correct interpretation of Mao’s thoughts being determined by political commissars, the book became what Leese describes as “the only criterion of truth” during the Cultural Revolution. After a period of “anarchic quotation wars”, when it was deployed as a weapon in a variety of political conflicts, Mao put the lid on the book’s uncontrolled use. Beginning in late 1967, military rule was imposed and the PLA was designated “the great school” for Chinese society. Ritual citation from the book became common as a way of displaying ideological conformity; customers in shops interspersed their orders with citations as they made their purchases...Studying the book was believed to have enabled peasants to control the weather... Long terms of imprisonment were handed out to anyone convicted of damaging or destroying a copy of what had become a sacred text. \=\

“During the Cultural Revolution study sessions were an unavoidable part of everyday life for people in China. Involving “ritualistic confessions of one’s errant thoughts and nightly diary-writing aimed at self-criticism”, historian Ban Wang writes, “may be seen as a form of text-based indoctrination that resembles religious hermeneutics and catechism” – a “quasi-religious practice of canonical texts”. \=\

Television During and the Cultural Revolution

The Cultural Revolution brought China's TV service to halt. Beijing TV Station announced: In answer to Chairman Mao's call that "you people should be concerned about the important affairs of our country and should carry out the Great Cultural Revolution to its full extent," we have decided to launch a general, all-out offensive on a tiny handful of inner-Party power holders who have been taking the capitalist road. As a result, from January 3, 1967 on, this station will suspend normal broadcasting service except on important matters and occasions. [Source: Morning Sun (morningsun.org) , Long Bow Group]

According to Morning Sun: TV stations were under tight control: Between 1967 and 1976, the only so-called "entertainment programs" shown on Chinese television were eight revolutionary model operas. A British broadcaster, who happened to visit China in 1970, found, much to his surprise, that within a 26-minute principal evening news broadcast by the Beijing TV Station, 18 minutes were devoted to rolling captions of Chairman Mao's quotations against a background of music praising Mao.

TV broadcasts started at 7 p.m. with Mao's portrait on the screen and the sound of The East Is Red, China's unofficial national anthem. These were followed by newscasts of such topics as commemoration of heroes, the work of educated youth in a remote village, reception of foreign visitors by the Chinese leaders, and the heroic struggle of the North Vietnamese. Next came revolutionary ballet and films, usually old Chinese movies about the anti-Japanese war or the war waged by the Communist Party against the Nationalists. At 10:30 p.m., the station signed off.

Revolutionary Opera and Jiang Qing

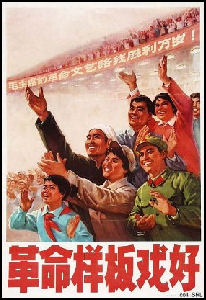

Revolutionary Opera created by Communists in the Cultural Revolution gloried farmers, workers and soldiers rather heroes from the feudal aristocracy. The plots revolved around class struggle and revolution and had titles like such as Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy.

The popular play that many scholars say triggered the entire Cultural Revolution was The Dismissal of Hai Rui from Office, a drama by historian Wu Han about an obscure Song dynasty official. The play was widely seen as as a traitorous critique of Mao's dismissal of Peng Dehuai, a military leader who criticized the Great Leap Forward.

Revolutionary opera

Mao’s wife Jiang Qing was put in charge of the arts during the Cultural Revolution. She and her group of loyalist intellectuals and artists controlled everything: film studios, operas, theatrical companies and radio stations. Jiang reviewed more than 1,000 operas and concluded that nearly all of them were unacceptable because they dealt with "emperors, officials, scholars and concubines." She commissioned a series of "revolutionary modern model operas” with heroic figured that displayed socialist virtues. These operas were based on Peking opera but featured Western devises that were deemed appropriate for furthering revolutionary goals.

Jiang Qing decided that eight operas were the only permitted forms of art in China, and they are heavily associated with the ideologically-charged violence of the period. Among the eight operas authorized by Jiang were The Girl with White Hair (about a woman who loses her natural coloring because of an evil landowner), Red Women's Detachment, and Songs of the Long March. The operas were adapted for symphony orchestras, dance troupes, piano music and even ethnic minority songs. In the 1960s, Chinese teenagers listened to songs form these operas while Americans were listening to the Beatles and the Supremes. Alex Ross wrote in The New Yorker, Red Detachment of Women has “a kitschily charming score in a light-classical vein, with an array of native-Chinese sounds.”

The Cultural Revolution also went abroad. In 1968, writer Paul Theroux observed a play in Africa by a group of Red Guard acrobats and actors about drilling for oil in Manchuria. "In the heat of the Ugandan night," he wrote, "they mimicked frostbite and hypothermia as they danced and drilled through layers of ice and rock. They dropped with exhaustion and were on the point of giving up altogether — no oil...Then after being inspired by some saying by Mao they went back to work and finally hit a gusher." [Source: Riding the Iron Rooster by Paul Theroux]

“Loyalty dances” were performed by grandmothers with bound feet. A typical Cultural Revolution song went something like this:

I love Beijing Tiananmen,

The sun rises on Tiananmen,

Our Great leader Chairman Mao"

See Separate Article: REVOLUTIONARY OPERA AND MAOIST AND COMMINIST THEATER IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Golden Mangoes

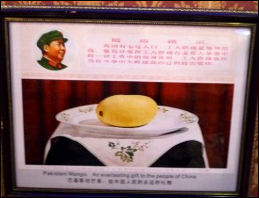

Mao and mangoes In the Mao era mangoes were greatly treasured. After Mao received a box of them as a gift from the foreign minister of Pakistan he had some distributed among groups of Communist Party workers. The fruit were received as proof of Mao’s godlike love of his subjects and were treated with religious awe. Some of the mangoes were boiled down and made into a precious elixir; others were pickled in formaldehyde and preserved on altars. Afterwards copies of mangoes were preserved in cases like the bones of saints. A multitude of objects with images of them were created.

At the height of the Cultural Revolution,Benjamin Ramm of BBC wrote, “To quell the forces that he had unleashed, Mao sent 30,000 workers to Qinghua University in Beijing, armed only with their talisman, the Little Red Book. The students attacked them with spears and sulphuric acid, killing five and injuring more than 700, before finally surrendering. Mao thanked the workers with a gift of approximately 40 mangoes, which he had been given the previous day by Pakistan's foreign minister."No-one in northern China at that point knew what mangoes were. So the workers stayed up all night looking at them, smelling them, caressing them, wondering what this magical fruit was," says art historian Freda Murck, who has chronicled this story in detail. "At the same time, they had received a 'high directive' from Chairman Mao - saying that henceforth, 'The Working Class Must Exercise Leadership In Everything'. It was very exciting to be given this kind of recognition." “This power shift — from the zealous students to the workers and peasants — offered respite from the anarchy. "Some people in Beijing told me that they perceived that Mao had finally intervened in the chaotic random violence, and that the mangoes symbolised the end of the Cultural Revolution," Murck says. == [Source: Benjamin Ramm, BBC, February 11, 2016 ==]

The mango craze began In 1968, when Mao decided to bring the Cultural Revolution movement back under the control of the Party. But officially he pronounced that from now on the working class should be leaders in everything. It was at precisely this time that Mao received a box of mangoes as a gift from the visiting foreign minister of Pakistan. The very same night Mao ordered that these exotic fruits should be presented to the workers. The mangoes were quickly seen as a symbol of Mao’s benevolence and devotion to the masses, and became the focus of cult admiration. The symbol soon entered popular culture, with mangoes decorating cups, bowls, cigarette packets, badges, blankets and other everyday objects. For more than a year China was gripped by mango fever. And then the mango vanished from the propaganda repertoire, as quickly as it had come.

Cult of the Mango During the Cultural Revolution

Benjamin Ramm of BBC wrote, “Zhang Kui, a worker who occupied Qinghua, says that the arrival of one of Mao's mangoes at his workplace prompted intense debate. "The military representative came into our factory with the mango raised in both hands. We discussed what to do with it: whether to split it among us and eat it, or preserve it. We finally decided to preserve it," he says. "We found a hospital that put it in formaldehyde. We made it a specimen. That was the first decision. The second decision was to make wax mangoes - wax mangoes each with a glass cover. After we made the wax replicas, we gave one to each of the Revolutionary Workers." [Source: Benjamin Ramm, BBC, February 11, 2016 ==]

“China has a long history of symbolic associations with food, which may have encouraged extravagant interpretations of Mao's gift. The mangoes were compared to Mushrooms of Immortality and the Longevity Peach of Chinese mythology. The workers surmised that Mao's gift was an act of selflessness, in which he sacrificed his longevity for theirs. Little did they know that he disliked fruit. Nor were they concerned to learn that Mao was simply passing on a gift he had already received. There is a tradition in China of zhuansong, or re-gifting. It may be regarded as vulgar in the West, but in China re-gifting is widely seen as a compliment, enhancing the status of both the giver and the recipient. ==

“The mangoes also proved to be a gift to the propaganda department of the Communist Party, which quickly manufactured mango-themed household items, such as bed sheets, vanity stands, enamel trays and washbasins, as well as mango-scented soap and mango-flavoured cigarettes. Massive papier-mache mangoes appeared on the central float during the National Day Parade in Beijing in October 1968. Far away in Guizhou province, thousands of armed peasants fought over a black and white photocopy of a mango.” ==

Mango Poems and Mango Tours

Benjamin Ramm of BBC wrote, “Workers were expected to hold the sacred fruit solemnly and reverently, and were admonished if they failed to do so. Wang Xiaoping, an employee at the Beijing No 1 Machine Tool Plant, received a wax replica. The fruit itself was destined for higher things. "The real mango was driven by a worker representative through a procession of beating drums and people lining the streets, from the factory to the airport," says Wang. The workers had chartered a plane to fly a single mango to a factory in Shanghai. When one of the mangoes began to rot, workers peeled it and boiled the flesh in a vat of water, which then became "holy" - each worker sipped a spoonful. (Mao is said to have chuckled on hearing this particular detail.) "From the very beginning, the mango gift took on a relic-like quality - to be revered and even worshipped," Cambridge University lecturer Adam Yuet Chau told the BBC. "Not only was the mango a gift from the Chairman, it was the Chairman."[Source: Benjamin Ramm, BBC, February 11, 2016 ==]

This association is reflected in a poem from the period.

Seeing that golden mango

Was as if seeing the Great Leader Chairman Mao!

Standing before that golden mango

Was just like standing beside Chairman Mao!

Again and again touching that golden mango:

the golden mango was so warm!

Again and again smelling the mango:

that golden mango was so fragrant! ==

“The mangoes toured the length and breadth of the country, and were hosted in a series of sacred processions. Red Guards had wrecked temples and shrines, but destroying artefacts is easier than erasing religious behaviour, and soon the mangoes became the object of intense devotion. Some of the rituals imitated centuries of Buddhist and Daoist traditions, and the mangoes were even placed on an altar to which factory workers would bow.” ==

Mango-Skeptics, Imelda Marcos and the End of Mangomania

Benjamin Ramm of BBC wrote, “But not everybody was so enthusiastic about the fruit. The artist Zhang Hongtu told me of his scepticism. "When the mango story was published in the newspaper, I thought it was funny, stupid, ridiculous! I'd never had a mango, but I knew it was a fruit, and any fruit will rot." Those who expressed their doubts, however, were severely punished. A village dentist was publicly humiliated and executed after comparing a "touring" mango to a sweet potato. The mango fever fizzled out after 18 months, and soon discarded wax replicas were being used as candles during electrical outages. [Source: Benjamin Ramm, BBC, February 11, 2016 ==]

“On a visit to Beijing in 1974, Imelda Marcos took a case of the Philippine national fruit - mangoes - as a gift for her hosts. Mao's wife, Jiang Qing, known as "Madame Mao" in the West, tried to replicate the earlier enthusiasm, sending the mangoes to workers. They dutifully held a ceremony and gave thanks, but Jiang Qing lacked her husband's sense of political timing. The following year, as Mao lay ill and with no clear successor in sight, she commissioned a new film, Song of the Mango, to enhance her credibility. But within a week of its release, Jiang was arrested and the film was taken out of circulation. It was the final chapter in the mango story. ==

“Now mangoes are a common fruit in Beijing, and Wang Xiaoping can buy "golden mango" juice whenever she likes. "The mystery of the mango is gone," she tells me. "It's no longer a sacred icon as before - it's become another consumer good. Young people don't know the history, but for those of us who lived through it, every time you think of mangoes your heart has a special feeling." ==

“Mao, like the mangoes he gave the workers, now lies preserved in wax in a crystal glass case. Historians have tended to regard the mango craze as a bizarre fad, but it is one of the few occasions when culture was created spontaneously from the bottom-up, initiated and interpreted by the workers. During a period of great cruelty, the mangoes represented for people an emblem of peace and generosity. They wanted to believe the promise written on the enamel trays: "With each mango, profound kindness." ==

Image Sources: Posters, Landsberger Posters http://www.iisg.nl/~landsberger/; photos, Ohio State University; Wiki Commons; History in Pictures blog; Everyday Life in Maoist China.org everydaylifeinmaoistchina.org

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2022