QING DYNASTY CULTURE

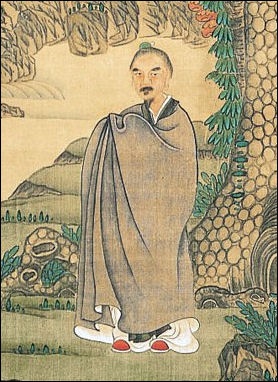

Chen Hongshu, self-portrait, 1635

Maxwell K. Hearn of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: The Manchus established their hegemony over Chinese cultural traditions as an important means of demonstrating their legitimacy as Confucian-style rulers. The court became a leading patron in the arts as China enjoyed an extended period of political stability and economic prosperity. The brilliant reigns of the Kangxi (r. 1662–1722) and Qianlong (r. 1736–95) emperors display a period when the Manchus embraced Chinese cultural traditions and the court became a leading patron in the arts as China enjoyed an extended period of political stability and economic prosperity. [Source: Maxwell K. Hearn, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

Wang Yimin, a specialist in ancient Chinese calligraphy at the Palace Museum, told the China Daily: . "Successive Manchu emperors, stigmatized by what they felt was their lack of cultural sophistication, went to great lengths to ensure their offspring would be raised in the most classic of the Han literary tradition. To submerge themselves in this tradition was to be able to communicate with society's elite and thus to gain legitimacy to rule. A vital part of that tradition is visual." [Source: Zhao Xu, China Daily, December 19, 2015]

Buddhism, particularly Tibetan Buddhism, made its presence felt. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “ In the Qing dynasty (1644-1911), many members of the imperial clan were devout followers of Buddhism. The courts in the Kangxi and Qianlong reigns witnessed the transcription and printing of the Kanjur Tripitaka in Tibetan and the Tripitaka in Manchu, while the Yongzheng Emperor (r. 1723-1735) selected and edited the contents of Record of Imperially Selected Lectures and Imperial Record of a Drop in an Ocean of Sutras. In the imperial palace, many buildings included lecture halls for Buddhist scriptures and places for offerings to Buddhist images, while numerous displays and collections of Buddhist paintings and sutra books were found at other locations. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei]

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In this Kangxi period culture began to flourish again. The emperor had attracted the gentry, and so the intelligentsia, to his court because his uneducated Manchus could not alone have administered the enormous empire; and he showed great interest in Chinese culture, himself delved deeply into it, and had many works compiled, especially works of an encyclopaedic character. The encyclopaedias enabled information to be rapidly gained on all sorts of subjects, and thus were just what an interested ruler needed, especially when, as a foreigner, he was not in a position to gain really thorough instruction in things Chinese. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

The Chinese encyclopaedias of the seventeenth and especially of the eighteenth century were thus the outcome of the initiative of the Manchurian emperor, and were compiled for his information; they were not due, like the French encyclopaedias of the eighteenth century, to a movement for the spread of knowledge among the people. For this latter purpose the gigantic encyclopaedias of the Manchus, each of which fills several bookcases, were much too expensive and were printed in much too limited editions. The compilations began with the great geographical encyclopaedia of Ku Yen-wu (1613-1682), and attained their climax in the gigantic eighteenth-century encyclopaedia T'u-shu chi-ch'eng, scientifically impeccable in the accuracy of its references to sources. Here were already the beginnings of the "Archaeological School", built up in the course of the eighteenth century. This school was usually called "Han school" because the adherents went back to the commentaries of the classical texts written in Han time and discarded the orthodox explanations of Zhu Xi's school of Song time. Later, its most prominent leader was Tai Chen (1723-1777). Tai was greatly interested in technology and science; he can be regarded as the first philosopher who exhibited an empirical, scientific way of thinking. Late nineteenth and early twentieth century Chinese scholarship is greatly obliged to him.

Website on the Qing Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Qing Dynasty Explained drben.net/ChinaReport ; Recording of Grandeur of Qing learn.columbia.edu Ming and Qing Tombs UNESCO World Heritage Site: UNESCO World Heritage Site Map ; Forbidden City: FORBIDDEN CITY factsanddetails.com/china; Wikipedia; UNESCO World Heritage Site Sites World Heritage Site ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Painting and Calligraphy: China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Painting, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Calligraphy, University of Washington depts.washington.edu ; Websites and Sources on Chinese Art: China -Art History Resources art-and-archaeology.com ; Art History Resources on the Web witcombe.sbc.edu ; ;Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Visual Arts/mclc.osu.edu ; Asian Art.com asianart.com ; China Online Museum chinaonlinemuseum.com ; Qing Art learn.columbia.edu Museums with First Rate Collections of Chinese Art National Palace Museum, Taipei npm.gov.tw ; Beijing Palace Museum dpm.org.cn ;Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org ; Sackler Museum in Washington asia.si.edu/collections ; Shanghai Museum shanghaimuseum.net

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: MING- AND QING-ERA CHINA AND FOREIGN INTRUSIONS factsanddetails.com; QING (MANCHU) DYNASTY (1644-1912) factsanddetails.com; MANCHUS — THE RULERS OF THE QING DYNASTY — AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; CHINESE PAINTING: THEMES, STYLES, AIMS AND IDEAS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE ART: IDEAS, APPROACHES AND SYMBOLS factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE PAINTING FORMATS AND MATERIALS: INK, SEALS, HANDSCROLLS, ALBUM LEAVES AND FANS factsanddetails.com ; SUBJECTS OF CHINESE PAINTING: INSECTS, FISH, MOUNTAINS AND WOMEN factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE LANDSCAPE PAINTING factsanddetails.com ; QIANLONG EMPEROR (ruled 1736–95) factsanddetails.com;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Qing Dynasty and Traditional Chinese Culture” by Richard J. Smith Amazon.com; “Splendors of China's Forbidden City: The Glorious Reign of Emperor Qianlong” by Chuimei Ho and Bennet Bronson Amazon.com; “Emperor Qianlong: Son of Heaven, Man of the World” by Mark Elliott and Peter N. Stearns Amazon.com; “Chinese paintings of the Ming and Qing Dynasties, 14th-20th century” by Edmund Capon and Mae Anna Pang Amazon.com; “Objectifying China: Ming and Qing Dynasty Ceramics and Their Stylistic Influences Abroad” by Ben Chiesa, Florian Knothe, et al. Amazon.com; “Raising the Dead and Returning Life: Emergency Medicine of the Qing Dynasty” by Lorraine Wilcox Amazon.com; "Forbidden City" by Frances Wood, a British Sinologist Amazon.com; “Chinese Dress: From the Qing Dynasty to the Present Day” by Valery Garrett Amazon.com; “Ruling from the Dragon Throne: Costume of the Qing Dynasty (1644-1911)” by John E. Vollmer Amazon.com; Painting: “Chinese Painting” by James Cahill (Rizzoli 1985) Amazon.com; “Three Thousand Years of Chinese Painting” by Richard M. Barnhart, et al. (Yale University Press, 1997); Amazon.com; “How to Read Chinese Paintings” by Maxwell K. Hearn (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2008) Amazon.com; “Chinese Brushwork in Calligraphy and Painting: Its History, Aesthetics, and Techniques” by Kwo Da-Wei Amazon.com; Art; “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Qing Dynasty Literati and Scholar-Artists

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In China, the literate elite were often referred to as the "literati." The literati were the gentry class, composed of individuals who passed the civil service exams (or those for whom this was the major goal in life) and who were both the scholarly and governmental elite of the society. The literati also prided themselves on their mastery of calligraphy. Often, as an adjunct to calligraphy, they were also able to paint. During the Qing dynasty, both the Individualists and the Orthodox school masters came from this elite scholar class. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu ]

Qianglong Emperor doing calligraphy

“The Scholar-Artists: The Individualist and Orthodox masters were proficient scholars who often embellished their paintings with poetry. These men were part of a long-standing tradition of the "scholar-artist" that had existed in China as far back as the 11th century. Members of the educated elite, also called the "literati," had already taken possession of calligraphy — the art of writing — as a form of self-expression. But by the 11th century, they began to apply the aesthetic principles of calligraphic brushwork to painting. They began by painting subjects that could be depicted easily with the brush techniques that they had mastered in the art of calligraphy, such as bamboo, rocks, and pine trees. This approach to subject matter set scholar-artists apart from commercial artists, who pursued a more representational manner.

“Wang Hui and the Orthodox School of Painting: It was a stroke of genius on the part of the Kangxi Emperor to enlist the foremost Orthodox school master, Wang Hui (1632-1717), to direct the painting of the monumental Southern Inspection Tour scrolls, the execution of which was sure to be an enormous challenge. Wang Hui was one of the leading artists of the time and an acknowledged master at creating long landscape compositions in the handscroll format. Furthermore, his selection immediately identified the Qing court with China's most revered artistic traditions.”

European Influences on Qing Culture

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “About the middle of the nineteenth century the influence of Europe became more and more marked. Translation began with Yen Fu (1853-1921), who translated the first philosophical and scientific books and books on social questions and made his compatriots acquainted with Western thought. At the same time Lin Shu (1852-1924) translated the first Western short stories and novels. With these two began the new style, which was soon elaborated by Liang Ch'i-Chao, a collaborator of Sun Yat-sen's, and by others, and which ultimately produced the "literary revolution" of 1917. Translation has continued to this day; almost every book of outstanding importance in world literature is translated within a few months of its appearance, and on the average these translations are of a fairly high level.

“A second group of Qing artists included those men who dedicated themselves to the preservation of Chinese traditional culture by returning to the careful study of a canon of earlier masters that had been defined in the 17th century. Their commitment to replicating and being inspired by this earlier canon of masterpieces led to the labeling of these artists as "the Orthodox school." The Orthodox masters made a point of first imitating these established earlier models and then trying to incorporate these stylistic traditions into their own work. They often created albums of paintings wherein each leaf would be devoted to the exposition of a specific earlier style. In this way, a particular album would demonstrate an individual's command over a whole range of earlier stylistic traditions. [Read more about traditionalists and "the Orthodox school" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History.].

“A third group of Qing artists included commercial and court artists who specialized in large-scale decorative works. Such artists were employed by the imperial court to produce documentary, commemorative, and decorative works for the imperial palaces. Masters of technique, these artists drew upon the representational styles of the Song dynasty, when meticulously descriptive painting techniques were highly revered. [Read more about professional and court artists at The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History.].

Chinese Approaches to the Work of Art

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Personal Expression Valued Over "Realism": Although "realistic" painting in the European style was very much in vogue at the Qing court, where it was appreciated for its documentary value in commemorating the Qianlong Emperor's exploits, it was not regarded as "high art." The Chinese and their Manchu rulers held to the belief that the highest form of pictorial expression was traditional Chinese painting, which privileged the personal expression of the individual artist over the representation of external appearances. Since the 14th century what mattered most in Chinese painting was the artist's ability to express his personal feelings — to create an image of his interior world — rather than to describe the external appearances of things. As a result, most Chinese painting connoisseurs regarded the European style as little more than a gimmick. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“The missionaries played an important part at court. The first Manchu emperors were as generous in this matter as the Mongols had been, and allowed the foreigners to work in peace. They showed special interest in the European science introduced by the missionaries; they had less sympathy for their religious message. The missionaries, for their part, sent to Europe enthusiastic accounts of the wonderful conditions in China, and so helped to popularize the idea that was being formed in Europe of an "enlightened", a constitutional, monarchy. The leaders of the Enlightenment read these reports with enthusiasm, with the result that they had an influence on the French Revolution. Confucius was found particularly attractive, and was regarded as a forerunner of the Enlightenment. The "Monadism" of the philosopher Leibniz was influenced by these reports.

“The missionaries gained a reputation at court as "scientists", and in this they were of service both to China and to Europe. The behaviour of the European merchants who followed the missions, spreading gradually in growing numbers along the coasts of China, was not by any means so irreproachable. The Chinese were certainly justified when they declared that European ships often made landings on the coast and simply looted, just as the Japanese had done before them. Reports of this came to the court, and as captured foreigners described themselves as "Christians" and also seemed to have some connection with the missionaries living at court, and as disputes had broken out among the missionaries themselves in connection with papal ecclesiastical policy, in the Yongzheng period (1723-1736; the name of the emperor was Shih Tsung) Christianity was placed under a general ban, being regarded as a secret political organization.

Qing-Era Literature

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The most famous literary works of the Manchu epoch belong once more to the field which Chinese do not regard as that of true literature—the novel, the short story, and the drama. Poetry did exist, but it kept to the old paths and had few fresh ideas. All the various forms of the Song period were made use of. The essayists, too, offered nothing new, though their number was legion. One of the best known is Yuan Mei (1716-1797), who was also the author of the collection of short stories Tse-pu-yu ("The Master did not tell"), which is regarded very highly by the Chinese. The volume of short stories entitled Liao-chai chich-i, by P'u Song-lin (1640-1715?), is world-famous and has been translated into every civilized language. Both collections are distinguished by their simple but elegant style. The short story was popular among the greater gentry; it abandoned the popular style it had in the Ming epoch, and adopted the polished language of scholars. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The Manchu epoch has left to us what is by general consent the finest novel in Chinese literature, Hung-lou-meng ("The Dream of the Red Chamber"), by Ts'ao Hsueh-ch'in, who died in 1763. It describes the downfall of a rich and powerful family from the highest rank of the gentry, and the decadent son's love of a young and emotional lady of the highest circles. The story is clothed in a mystical garb that does something to soften its tragic ending. The interesting novel Ju-lin wai-shih ("Private Reports from the Life of Scholars"), by Wu Ching-tzu (1701-1754), is a mordant criticism of Confucianism with its rigid formalism, of the social system, and of the examination system. Social criticism is the theme of many novels. The most modern in spirit of the works of this period is perhaps the treatment of feminism in the novel Ching-hua-yuan, by Li Yu-chên (d. 1830), which demanded equal rights for men and women.

“The drama developed quickly in the Manchu epoch, particularly in quantity, especially since the emperors greatly appreciated the theatre. A catalogue of plays compiled in 1781 contains 1,013 titles! Some of these dramas were of unprecedented length. One of them was played in 26 parts containing 240 acts; a performance took two years to complete! Probably the finest dramas of the Manchu epoch are those of Li Yu (born 1611), who also became the first of the Chinese dramatic critics. What he had to say about the art of the theatre, and about aesthetics in general, is still worth reading.

Qing Dynasty Art

In the Silence by Dong Qichang

Art produced during the Qing period was particularly ornate. Incorporating Tibetan, Middle Eastern, Indian and European influences, it included elaborately carved wood, baroque ceramics, heavily embroidered garments, and intricately worked gold and rhinoceros horn. Among the more extravagant pieces of Qing art are silk costumes made with applique embroidery; a royal hat made of sable, silk floss, gold, pearls and feathers; and a five-foot-high cloisonne elephant with a lamp on its back.

Holland Cotter wrote in the New York Times: “What the Qing wanted in court art was more: more ingenuity, more virtuosity, more bells and whistles, extra everything. When it came to scale, they went for extremes, the teensy and the colossal, cups the size of thimbles, jades the size of boulders. The Confucian middle way was not their way.”

Qing art included large-scale portraits, silk robes, painted screens, handscrolls, headdresses, fans, bracelets and furniture. Some of the best art works were small. A 19th century hair ornament with dragons was decorated with pearls, coral, kingfisher feathers and silver with gilding. On a larger, Buddhist stupa made from gold and silver, Sebastian Smee wrote in the Washington Post: The stupa, which is adorned with coral, turquoise, lapis lazuli and other semiprecious stones, was commissioned by the Qianlong Emperor in honor of his mother, the Empress Dowager Chongqing, after her death. Inside is a box with a lock of her hair. The Qianlong Emperor micromanaged its creation, continually issuing new instructions, so that it ended up being twice as tall and far more elaborate than the original design. [Source: Sebastian Smee, Art critic, Washington Post, April 12, 2019]

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In painting, European influence soon shows itself. The best-known example of this is Lang Shih-ning, an Italian missionary whose original name was Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766); he began to work in China in 1715. He learned the Chinese method of painting, but introduced a number of technical tricks of European painters, which were adopted in general practice in China, especially by the official court painters: the painting of the scholars who lived in seclusion remained uninfluenced. Dutch flower-painting also had some influence in China as early as the eighteenth century. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Schools of Art During the Qing Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Art during the Qing dynasty was dominated by three major groups of artists. The first, sometimes called "the Individualists," was a group of men largely made up of loyalists to the fallen Ming dynasty. The Individualists referred to themselves as "leftover subjects of the Ming" and practiced a very personal form of art that sought to express their reaction to the Manchu conquest — either a sense of resistance, reclusion, or sadness over the fall of the Ming dynasty. They often removed themselves not only from government circles but also from society, often by becoming Buddhist monks. The Individualists sought to express in their art their own feelings regarding the fall of the Ming dynasty and the conquest of China by a group of people whom they regarded as barbarians. These artists focused particularly on the expressive potential of painting and sought not to emulate past models so much as to use poetry, painting, and calligraphy in ways that would express their feelings of defiance and loss over the fall of the Ming dynasty. [Read more about "the Individualists" at The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History.] [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“The Importance of Poetry for Artists and Connoisseurs: Chinese literati artists often wrote poems directly on their paintings. This practice emphasized the importance of both poetry and calligraphy to the art of painting and also highlighted the notion that a painting should not try to represent or imitate the external world, but rather to express or reflect the inner state of the artist. The artist's practice of writing poetry directly on the painting also led to the custom of later appreciators of the work — perhaps the initial recipient of the painting or a later owner — adding their own reactions to the work, often also in the form of poetry. These inscriptions could be added either directly on the surface of the painting, or sometimes on a sheet of paper mounted adjacent to the painting. In this way some handscrolls accommodated numerous colophons by later owners and admirers. Thus in Chinese art the act of ownership entailed the responsibility of not only caring for the work properly, but to a certain extent also recording one's response to it. [Read about Li Gonglin, the Song dynasty painter who gave form to the ideal of painting as a reflection of the artist's mind and an expression of deeply held values, at The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History. Also learn about seals, inscriptions, and colophons at The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Explore and Learn website, A Look at Chinese Painting.].

“The Qianlong Emperor was an avid collector and connoisseur of Chinese art, and the number of paintings and artifacts collected during his reign was unprecedented. Many palace halls were used specifically for the Emperor to admire and study works of art. The Qianlong Emperor had a tendency to admire the works he collected and commissioned by adding a great number of seals and inscriptions — usually in the form of poems — to the works. In so doing, the emperor not only endowed these works of art with the imperial imprimatur but also, by leaving his mark on some of the most important works of Chinese art, asserted his control over Chinese culture and his legitimacy as the ultimate connoisseur of Chinese art. Often he must have had ghost writers helping him inscribe these poems, but he did write many of them himself. In fact, the Qianlong Emperor is said to have composed some 40,000 poems, and many of them are inscribed on the enormous collection of paintings amassed during his reign. As a result, the Qianlong Emperor's inscriptions and seals appear on hundreds of the most important Chinese paintings that exist today.

“The Work of Art as a Dialogue with the Past: The Role of Owners and Connoisseurs: One of the most extraordinary characteristics of Chinese painting is that, in a way, a painting is never quite finished. What does this mean? Just as the artists themselves used poetry as a medium of expression in painting, later appreciators of a painting felt free to add to it by writing a poem in response to the work, or sometimes just adding a personal seal, directly on the surface of the painting or to the silk mounting bordering the painting. In this way a painting remains "open-ended," and viewing a painting is like engaging in an ongoing conversation, not only with the artist, but with all the people who have in the past owned the work and have recorded their response to it. And through this visual record, a painting's provenance can be traced, so that literally written on the surface of the painting is the very history of who owned it, how people over time have appreciated it, and how different eras saw its merits in a different light. When a connoisseur looks at a painting today, he or she not only examines the work, but takes great delight in seeing which other collectors owned it, and what some of these owners and other commentators have had to say about it.”

Qing Dynasty Painting

Wang Shimin illustration of a Du Fu poem

According to the Shanghai Museum:“ Two prevailing trends represented by "Four Wangs"of old style and "Four Monks" of fresh style appeared in the early Qing dynasty. In the middle Qing, a group of painters in the Yangzhou area used novel style to express their charm and personality and formed the "Yangzhou School". By the late Qing, a more gentle and delicate style emerged. At the same time, some painters such as Wu Changshuo and Zhao Zhiqian initiated a Xieyi style for flower and bird painting. After the mid-19th century, many painters and artists gathered in some coastal cities with developed economy such as Shanghai and Guangzhou and formed new styles or schools such as "Shanghai School" and "Lingnan School", which influence Chinese painting even today. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

In the middle of the Qing dynasty, the Loudong and Yushan School dominated painting circles with styles derived from the ‘Four Wangs’. Their numerous followers gradually evolved a more conservative style of painting. The Qing dynasty rebuilt the Imperial Art Academy which flourished from Kangxi to Qianlong reigns. Landscape paintings in the Art Academy were greatly influenced by the style of the ‘Four Wangs’. Flower-and-bird paintings flourished depicting nature and adopting the ‘Boneless’ painting methods of the Yun School. The Imperial Art Academy also recruited some Western painters for the inner imperial court. The Western style of expression using light and perspective influenced Academy artists and produced a new style combining both Chinese and Western traditions. In the Yangzhou area, a group of scholars in disfavor made their living as painters. Their works, which used novel expressive composition and strong personality, were referred to as the ‘Yangzhou School’.

By the late Qing dynasty, the landscape paintings of the Four Wangs and flower-and-bird paintings of the Yun School were in decline. A more gentle and delicate style emerged. The increasing study of stone steles stimulated painters to evolve a new painting style. Wu Xizai, Zhao Zhiqian and Wu Changshuo were representatives of this painting style which ushered in a new bold and vigorous Xieyi style of flower-and-bird painting. After the mid 19th century, Shanghai and Guangzhou were opened as trading ports and soon became metropolitan and cosmopolitan cities attracting varieties of painters and artists. Embodying the spirit of the times, the works of these artists combined Western artistic elements with individual styles. Aside from the Art Academy style, these painters became known as the ‘Shanghai School’ and ‘Lingnan School’. Their works have an influence on Chinese painting even today.

Qing Dynasty Artists

Maxwell K. Hearn of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: Three principal groups of artists were working during the Qing: the traditionalists, who sought to revitalize painting through the creative reinterpretation of past models; the individualists, who practiced a deeply personal form of art that often carried a strong message of political protest; and the courtiers, the officials, and the professional artists who served at the Manchu court." [Source: Maxwell K. Hearn, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

During the Qing Period “Chinese court painters mastered the rudiments of Western linear perspective and chiaroscuro modeling, creating a new, hybrid form of painting that combined Western-style realism with traditional brushwork. Many Ming officials and loyal subjects withdrew from public service after the fall of the Ming dynasty and lived in enforced retirement, pursuing personal and artistic self-cultivation. While the early Manchu court favored a colorful figurative style, exemplified by the imposing image of Emperor Guan, a Chinese god whose martial prowess became a symbol of Manchu power, China's scholarly elite was deeply influenced by the theories and art of the late Ming artist, collector, and theorist Dong Qichang (1555–1636). Dong and his circle developed a revolutionary theory of literati painting based on a study of the old masters that became the foundation of a systematic stylistic reconstruction of landscape painting. Emphasizing the distinction between art and nature, Dong maintained: "If one considers the wonders of nature, then painting cannot rival landscape. But if one considers the wonders of brushwork, then landscape cannot equal painting." \^/

“During the early Qing period, this traditionalist theory became the foundation of a new orthodox style under the leadership of Dong's disciple, Wang Shimin (1592–1680). Wang was an accomplished amateur painter who built an important collection of old masters based on Dong's advice. It was this corpus of prime models that helped to define the orthodox lineage of scholar painting for Wang and his followers—later known collectively as the Orthodox School. Wang Shimin and his friend Wang Jian (1598–1677) were the senior members of this school, but they were outshown by their brilliant pupil Wang Hui (1632–1717). Wang Hui made it his objective to integrate the descriptive landscape styles of the Song dynasty (960–1279) with the calligraphic brushwork of the Yuan dynasty (1279–1368) to achieve a "great synthesis." Wang Shimin's other preeminent disciple was his grandson, Wang Yuanqi (1642–1715)—the youngest of the so-called Four Wangs. Wang Yuanqi pursued a rigorously abstract style in the manner of Dong Qichang that could accommodate learned references to the past without sacrificing his own artistic identity. Two other important disciples of Wang Shimin were Wu Li (1632–1718) and Yun Shouping (1633–1690). \^/

Representing Space and the External World

white rabbit making elixir of immortality

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The painters of the Qing dynasty were inheritors of a tradition that was already more than a thousand years old. By the 13th century, Chinese artists had mastered the illusion of recession in space. But after this time, the representation of space and the description of the external world gradually ceased to be the principal objective of artists. Working on a flat surface — such as a canvas or a scroll — an artist faces the challenge of creating the illusion of three-dimensional forms on a two-dimensional surface. This is a problem for which artists both in the East and the West found solutions, but their solutions were very different. European painting after the 15th century tended to treat a painting as though the canvas were a window through which an illusionistic three-dimensional scene could be viewed; Chinese painting created the experience of space by means of a moving perspective that allowed the viewer's eye to explore the pictorial space from a shifting vantage point, so that, in the case of a long handscroll such as those chronicling an emperor's journey, space is experienced through the continuous unrolling of the work. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“European Approaches to Representing Space: In the West, in Greco-Roman times and again in the Renaissance, artists created the illusion of spatial depth on a flat surface through the use of linear perspective, which meant that implied parallel lines were drawn to intersect at an imaginary point on the horizon called the "vanishing point," and all forms were rendered in scale and positioned to correspond to these guiding lines. As a result, there is a kind of geometric logic to the composition in Western painting, and the viewing frame (which can be seen all at once, unlike in a Chinese handscroll painting) was experienced as a kind of "window" onto another world. [See an etching that uses linear perspective, by the 18th-century Italian artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi, on The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History.].

“Pictorial space in Chinese painting is defined somewhat differently from the foreground, middle ground, and background typically found in traditional Western painting. In Scroll Three of the Kangxi Inspection Tour series, three distinct classifications of pictorial space, as defined by the 11th-century artist Guo Xi, can be seen in the artist's treatment of the mountains: "From the bottom of the mountain looking up toward the top, this is called 'high distance' (gaoyuan). From the front of the mountain peering into the back of the mountain, this is called 'deep distance' (shenyuan). From a nearby mountain looking past distant mountains, this is called 'level distance' (pingyuan)." — From Guo Xi and Guo Si, Lin quan gao zhi (Lofty Ambitions in Forests and Streams), in Yu Jianhua, ed., Zhongguo hualun leibian (Compendium of essays on Chinese paintings).

“Chinese Approaches to Representing Space: Chinese artists' approach to the problem of representing spatial depth on a flat surface is quite different from that of their Western counterparts. In fact, the very formats that are used in Chinese painting — particularly the long handscroll — have an impact on how pictorial space itself is conceptualized in the Chinese painting tradition. Imagine unrolling a scroll painting, for instance, from right to left as one would in viewing a Chinese painting. The scroll may be as long 60, 70, or even 80 feet, so it is impossible to see much more than a small section of the entire painting at once. And in fact, the work was not meant to be seen all at once. Unlike a traditional Western painting, which is contained within a distinct frame, a painting on a long scroll that has to be unrolled section by section would not make sense visually if it were composed with a technique such as linear perspective, which depends on the use of a single, fixed vanishing point. In a long scroll, the viewer controls the boundaries of the viewing frame at any single moment, and the pictorial space unfolds as the viewer unrolls the scroll. In this way, the handscroll format requires that the pictorial space remain fluid. As in traditional Western compositions, there is a foreground, a middle ground, and a far distance, but the artist continuously shifts the focus of the composition so that the viewer's apparent vantage point is constantly changing, enabling him or her to easily navigate the pictorial space unhindered by the constraints of a fixed vanishing point.”

Zhu Da (1626–1705) and Zhu Ruoji (1642–1707)

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Two of the most outstanding artists of the early Qing period were descendants of the Ming royal house :Zhu Da (1626–1705) and Zhu Ruoji (1642–1707), both of whom became better known by their assumed names, Bada Shanren and Shitao. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“A scion of the Ming imperial family from a branch enfeoffed in Nanchang, Jiangxi Province, Zhu Da became a "crazy" Buddhist monk, shamming deafness and madness in order to escape persecution after the fall of the Ming dynasty. Lodging his feelings of frustration and vulnerability in his art, he created a deeply personal expressionist style that reflects his ambivalence about his life in hiding and his failure to acknowledge his identity as a Ming prince. \^/

“Shitao was only two years old when the Ming dynasty fell. Saved by a loyal retainer, he was given sanctuary and anonymity in the Buddhist priesthood. In the late 1660s and 1670s, while living in seclusion in temples around Xuancheng, Anhui Province, he trained himself to paint. After many years of wandering from place to place in the south and spending nearly three years in Beijing, Shitao moved to the commercial center of Yangzhou around 1695, where he renounced his status as a Buddhist monk and supported himself through his painting. Drawing upon his love for natural scenery and his technical facility with brush and ink, Shitao created the most original landscape style of the seventeenth century. \^/

Qianlong Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour

Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour Scrolls

The Kangxi Emperor and The Qianlong Emperor employed some of China's best artists to record their Southern Inspection Tours on scrolls. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Qianlong Emperor's tour scrolls were begun in 1764 by the court artist Xu Yang (act. ca. 1750-after 1776), who was very much influenced by the European traditions of perspective and figural representation. Wang Hui, who began the Kangxi Emperor's tour scrolls in 1691, was one of the foremost painters of the Orthodox School, whose members dedicated themselves to the preservation of Chinese traditional culture by returning to the careful study of a canon of earlier Chinese masters. Thus, it is not surprising to compare the two sets of scrolls and find that they differ radically in their approach to the representation of space and the treatment of figures. A telling example is the comparison of two specific scrolls, the seventh scroll in the Kangxi Emperor's tour series and the sixth scroll in the Qianlong Emperor's tour series, which both feature the Grand Canal and the city of Suzhou. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“In the Kangxi scroll, Wang Hui's figures are painted in a stylized, almost cartoon-like style that gives them a tremendous amount of buoyancy and expressive energy. The figures in the Qianlong scroll, on the other hand, are handled in a more European style and are anatomically more accurate, but they look stiff and posed, as though they are frozen in space and time. Xu Yang's figures are more three-dimensional in their representation, and therefore more "realistic" than their counterparts by Wang Hui, but, paradoxically, they actually seem to have less animation and life than Wang Hui's figures.

“A comparison of the two artists' approaches to the representation of space in the tour scrolls reveals the limitations of translating the European style to the Chinese scroll format. Influenced by the Western technique of linear perspective, Xu Yang strives in the sixth Qianlong scroll to maintain a consistent vantage point in his representations of the Grand Canal and the route of the Qianlong Emperor into Suzhou. The Canal is presented as though the viewer were always looking from the east toward the west. But in order to maintain the consistency of this viewpoint, Xu Yang had to present Tiger Hill, one of the scenic highlights on this leg of the tour route, from the back rather than from the front, which would have been its characteristic and thus, more recognizable, view. In the seventh Kangxi scroll, on the other hand, Wang Hui had no problem reorienting the mountain to present it from its more characteristic frontal view, which is precisely the way a Chinese map maker would visualize a mountain. Xu Yang, in trying to maintain a consistent reference point based on linear perspective, could not reorient the mountain suddenly and show it from the other side. So again, as with the treatment of figures, the commitment to pictorial realism in fact became a limitation to the artist in significant ways. Though the European style added a certain kind of illusionary realism to the depiction of Qianlong's southern inspection tour, it could be argued that it also detracted from one of the most important functions of these scrolls as historical documents, which was to highlight the significance of the emperor's visit to important sites (such as Tiger Hill and the Grand Canal).”

Qing Dynasty Portraits

Kanxi Emperor portrait

Large wall-size portraits of ancestors were produced for the aristocracy and ruling class during the Qing dynasty. They feature realistic seated renderings of individual painted in bright colors. They were often placed over family altars.

The paintings were regarded as mediums for communications to deceased relatives. The Chinese have traditionally believed the dead didn't die they just went to a different world where they could be contacted by the living. The dead were believed to want to hear news and receive offerings and sacrifices from time to time by living relatives.

The Shanghai School was an influential painting movement founded in the mid-19th century that is credited with combining traditional Chinese ink paintings with modernist trends. Incorporating heavy black strokes to outline figure and bring attention to details, it influenced Japanese wood block printing and early manga art among other things. Important Shanghai School artists included Qin Zuyong (1825-1884) and Qian Huian (1833-1911).

Describing a work called Kingyo-zu by the artist named Xugu Christoph Mark wrote in the Daily Yomiuri: “Light touches diluted ink to create reflections on water as abstract goldfish swim beneath...The scant use of color — a reddish orange for the fish — is characteristic of...paintings that rely heavily on inking skills to convey what color would be used for in other styles."

Yangzhou Art and the Anhui and Nanjing Masters

Maxwell K. Hearn of The Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “The city of Yangzhou, located along the Grand Canal between the Huai salt fields and the Yangzi River, became a prosperous commercial hub during the Qing dynasty thanks to the salt monopoly centered there. During the eighteenth century, the city surpassed even Suzhou in the number of important artists active there, as the burgeoning fortunes of salt merchants and other entrepreneurs created opportunities for artistic experimentation as well as conspicuous consumption. [Source: Maxwell K. Hearn, Department of Asian Art, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Yangzhou's mercantile elite supported a diverse array of artists who worked in two distinct pictorial traditions. One group, exemplified by Yuan Jiang (active ca. 1690–ca. 1746) and members of his atelier, worked in the courtly tradition, producing large-scale, richly detailed works in mineral pigments on silk that epitomize the Yangzhou taste for ostentatious display. Another group of artists, later known as the "Eight Eccentrics of Yangzhou," drew inspiration from the highly individualistic works of Shitao. Practicing a self-expressive, calligraphic painting manner, these artists specialized in figural subjects or auspicious flower and bird images that appealed to the tastes of a broader public and were less demanding as well as more commercially viable than landscape painting. \^/

According to the dictates of Confucian tradition, a man may not serve under two dynasties. As a result, many Ming officials and loyal subjects withdrew from public service after the fall of the Ming dynasty and lived in enforced retirement, pursuing personal and artistic self-cultivation. Escaping the chaos of the Manchu conquest, many of these artists found sanctuary outside traditional centers of culture. Lacking access to important collections of old masters, they drew inspiration from the natural beauty of the local scenery. One group of Ming loyalists living in Anhui Province, a prosperous region known for its outstanding paper and ink, saw in the rugged cliffs and craggy pines of Mount Huang (Yellow Mountain) a world free from the taint of Manchu occupation. Inspired by the Yuan-dynasty recluse-painter Ni Zan (1306–1374), who was known for his lofty moral character, these artists emulated Ni's minimalist compositions and "dry-brush" painting style, features that became hallmarks of the so-called Anhui School.

Nanjing, the Ming dynasty's secondary capital, remained a haven for loyalists during the early Qing. A center of Jesuit missionary activity since the late sixteenth century—it was once the home of Matteo Ricci (1552–1610)—Nanjing was also one of the first places where Chinese painters began to incorporate Western ideas of shading and perspective in their depictions of local scenery. \^/

“The most innovative Nanjing master was Gong Xian (ca. 1618–1689), who practiced a densely textured, monumental landscape style in which he was able to suggest volume and mass by varying the density and darkness of his ink dots. This modeling technique is highly schematic, and there is no single light source as in Western painting, but Gong's interest in the effects of light and shade probably owes something to the influence of European engravings and paintings. Zhang Feng (active ca. 1636–62), whose father died in 1631 while defending the Ming against early incursions by the Manchus, withdrew from society after the fall of the Ming and became associated with the Buddhist church. Zhang's paintings present images of reclusion in the pale, dry style of Ni Zan. \^/

“Among the more conservative masters working in Nanjing were Ye Xin (active ca. 1640–73) and Fan Qi (1616–after 1694), both of whom worked in an unusually precise and realistic style. Both specialized in small-scale gemlike paintings depicting the rural scenery around their native city. Sensitive and lyrical recorders of the familiar, these artists were also innovative experimenters with light, atmosphere, and color whose art reflects a creative response to Western influences recently introduced to China by the Jesuits." \^/

Tibetan Art in the Qing Collection

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The early Qing emperors were very knowledgeable in the ways of ruling, so they knew how to use the power of religion to win over other peoples. Before the 17th century, Tibetan Buddhism had already become the religion of the Manchus and was transmitted among Mongolian tribes. The Qing court further promoted Tibetan Buddhism and, after the 17th century, made it the most common belief system among Tibetan, Mongolian, and Manchu tribes in order to hold them together and keep harmony.

The “Golden mandala inlaid with coral and turquoise” measures 38.6 x 27.4 centimeters. This splendid mandala is stored in a refined leather container made in the Qianlong reign (1736-1795). Inside the container cover is a label of white fine silk that records in four languages (Manchu, Chinese, Mongolian, and Tibetan) an important historical event of the Qing dynasty. The mandala was offered to the Hsi-huang Temple and had been brought to the court by the Fifth Dalai Lama via Hsi-ning and Inner Mongolia in 1652, during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor. This mandala, against this backdrop of interaction between religion and politics, therefore has particular significance. On one hand, the Qing court received the blessings of the Dalai Lama from Tibet, confirming the mutual friendship between these two regions, which also spilled over to Mongol tribes. On the other hand, the Dalai Lama was able to spread his Yellow Hat sect eastward and popularize it with the support of the Qing court, thereby stabilizing his religious and political status in Tibet.

“The mandala, known as a kilkhor in Tibetan, is a circular symbol of the Buddhist universe. The top of the cover of this mandala is composed of evenly cut and graded pieces of turquoise divided into tiers and shapes piled and inlaid. Mount Sumeru appears at the center of the universe and is symbolically represented here with a great continent in each of the four directions. Encircling the rim are pieces of large, round, colorfully red coral. The wall of the mandala is done in repousse low-relief sculpting from the reverse, creating decoration of fine stalks of lotus with Buddhist treasures. The rims are finely worked in a variety of manners. Regardless of technique or materials, this work represents a masterpiece of craftsmanship.

European Influences on Qing-Era Chinese Painting

White Falcon by Giuseppe Castiglione

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Beginning in the late 16th and early 17th centuries, European Jesuit missionaries began to enter China and serve at the imperial court. Many of these missionaries brought engravings, illustrated books, and paintings with them and it was through these visual materials that Chinese were first introduced to Western linear perspective and the use of shading to model forms as if they were illuminated by a single light source (called "chiaroscuro," an Italian word literally meaning "light-dark"). [See a charcoal drawing that uses chiaroscuro shading, by the 15th-century Italian artist Leonardo da Vinci, on The Metropolitan Museum of Art's Timeline of Art History.] [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Maxwell K. Hearn, Consultant learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu ]

“The Chinese were impressed with the Europeans' techniques for creating the illusion of recession on a flat pictorial surface. This was particularly true in court circles, where emperors quickly realized the extent to which this new style of painting could serve well to commemorate and document their activities in a way that would be all the more powerful and convincing because of its realism. It is important to note, however, that even as "realistic" painting in the European style was very much in vogue at the Qing court, where it was appreciated for its documentary value, it was never regarded as "high art." Chinese art had long moved away from a representational style to one that privileged the personal expression of the individual artist over the representation of external appearances of nature.

One Jesuit artist in particular, Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) — who served under three Qing emperors (including the Kangxi Emperor and his grandson, the Qianlong Emperor) and even had a Chinese name, Lang Shining — had a major impact on documentary painting at the Qing court. The Qianlong Emperor's Southern Inspection Tour scrolls were not painted by Castiglione, but the influence of his style is clearly evident and becomes especially salient when the Qianlong Emperor's tour scrolls are compared to the Kangxi Emperor's tour scrolls, which were painted about 70 years earlier.

Sebastian Smee wrote in the Washington Post:“The Qing excelled at assimilating different cultural traditions, including Western-style pictorial influences. The Qianlong Emperor, in particular, was fond of an attractive hybrid of Western and Chinese picture-making known as “scenic illusion painting.” A lovely example” of this “is a large painting of the emperor’s young, chubby-cheeked son, the future Jiaqing Emperor, waving out at the viewer, while his mother, believed to be the third-rank consort, Ling, stands solicitously beside him. As in Velazquez’s “Las Meninas,” the implied viewer is the child’s father — in this case the emperor himself.

“The painting doubles as a view through a window. Trompe l’oeil window frames and tricks of perspective make it seem as if mother and child are in a room between the emperor’s own (where we are) and a scenic exterior replete with bamboo grove, rocks and auspicious peonies. To reinforce the illusion and the dollhouse effect, the entire top half of the painting is given over to an empty room upstairs. [Source: Sebastian Smee, Art critic, Washington Post, April 12, 2019]

Giuseppe Castiglione

Giuseppe Castiglione (1688-1766) was an Italian Jesuit who went by the Chinese name of Lang Shining. He came to China as a Catholic missionary and stayed on in China, serving as court painter under the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong Emperors. Castiglione arrived in China in 1715 at the age of 27 to do missionary work and was summoned to the court, where he came to serve in the Painting Academy. Castiglione fused traditional Chinese painting methods with Western techniques of perspective. He brought the realistic techniques of European oil painting and one-point perspective with him to the court. Castiglione excelled at bird-and-flower subjects "sketched from life" and was especially renowned for his depictions of horses. [Source:

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Giuseppe Castiglione was born in Milan, Italy, and studied painting since youth, joining the Jesuit society in Genoa at the age of 19, taking up the study of painting and architecture. When the Qing court in China made a request for a Western painter, word reached the Vatican in Rome and Castiglione was chosen to go. In 1709 he first went to Lisbon, Portugal, and, after several years, finally left for China in 1714, arriving in Macao during the following year (the 54th of the Kangxi emperor's reign). By the end of 1715, Castiglione (and his reputation in painting) had reached Beijing, catching the attention of the court, where, under the Chinese name Lang Shining, he was assigned as an artist. All in all, Castiglione served the Qing imperial household under the Kangxi, Yongzheng, and Qianlong emperors for nearly 51 years. Following his death from illness in 1766, Qianlong decreed that, in addition to Castiglione's official rank as "Administrator of Imperial Parks," he be posthumously promoted to Vice Minister.

“One Hundred Horses” an ink and colors on silk handscroll, nearly eight meters in length and painted in 1728, is Castiglione most famous work. Marina Kochetkova wrote in DailyArt Magazine: He painted it largely in a European style. Nevertheless, here too Castiglione reduced the dramatic chiaroscuro shading. There are only traces of shadow under the hooves of the horses. You can also see some of the horses are in a ‘flying gallop’ pose that was not conventional in European paintings. Most of Castiglione’s works are painted in tempera on silk, and thus he had to adapt to the Chinese style of working. Painting on silk does not allow for corrections. Therefore, Castiglione had to work out every detail on paper before transferring the idea to silk. [Source: Marina Kochetkova, DailyArt Magazine, June 18, 2021]

Castiglione depicts horses swaying on the grass or frolicking near each other, just as in Li Gonglin’s painting. Figures are often shown foreshortened. Although he paints trees in the traditional Chinese style, the artist uses shading. But the contrast between light and dark is minimized.” In one scene “You can see three horses have already crossed the river while others follow behind them. Some horses are quenching their thirst by the river. More are resting quietly, frolicking with their young offspring. In Chinese art, horses represent speed, endurance, and victory. Certain trees also signify different ideas. For example, the oak is a symbol of masculine strength. You can see the willow tree which is a Buddhist symbol of humility. The pine tree signifies longevity and resilience. Finally, red maple leaves almost always convey the autumn season.”

“White Falcon, an ink and colors on silk hanging scroll, measuring 123.8 x 65.3 centimeters, is another beautiful Castiglione work. According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: He excelled at Western techniques to render subjects, his paintings featuring color washes and the effects of light and shadows. This work depicts a white falcon with Western painting techniques. The eyes and even the white feathers all emphasize the effect of light. The background of a pine tree and mountain spring was likely by a painter specializing in traditional Chinese techniques. This bird of prey was submitted as tribute by Fuheng in 1751, Castiglione being about 62 years old at the time.

Qing Dynasty Crafts

meat-shaped stone kept in a Curio cabinet

In Imperial times, luxury art and crafts were indications of status and there was a certain hierarchy among the individual crafts. Jade carvings and lacquerware were more highly esteemed than ceramics. Jade was especially prized because of it symbolic value and the fact it was difficult to carve. Much of the National Palace Museum in Tapei’'s collection of crafts belonged to the Qing dynasty (1644-1911) court. Pei-chin Yu wrote for the National Palace Museum, Taipei:“The emperors of the Qing dynasty had many treasures in their possession. Some of these prized possessions were finely crafted and richly decorated utensils used for imperial court life, and some were simply for the emperor's enjoyment. All items from the Qing imperial collection, from richly enameled ceramics to watches and snuff bottles, represent the imperial lifestyle of the Qing. They are also an important sign of the on-going trade between China and the West.

Tsai Mei-Fen wrote in the Taiwan Today: “ Buddhist implements reveal the court's religious leanings, clothing and jewelry provide a glimpse of the official Qing hierarchy, snuff bottles give an indication of royal habits and ru-yi scepters provide an example of the extravagant gift-giving within the court. The collection also includes tribute objects that reveal the intermingling of characteristics of Chinese, Japanese and Western art, as well as intricate curio boxes that display the ingenuity of the era's craftsmen. [Source: Tsai Mei-Fen,Taiwan Today, April 2009. Tsai Mei-fen is a curator at the National Palace Museum, Taipei]

Among the items the emperors kept in miniature curio cabinets were small combs, tea containers, censers, incense, small knifes, nail files, forks, tweezers, brushes, pens, books, ink slabs, ink, ink cases, paper, brushes, brushwashers, brush-racks, water containers, glue boxes, seals, seal ink, and carved decorative pieces made from bamboo, wood, enamel, bronze, porcelain, ivory, gold, silver, rock-crystal and jade. The tiny compartments, shelves, drawers and boxes were often connected in elaborate, cryptic ways.

See Separate Article TREASURES OF THE CHINESE EMPEROR: IVORY CARVINGS, RHINOCEROS HORN CUPS AND CURIO CABINETS factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Jade, Palace Museum, Taipei Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021