WESTERN ZHOU: UTOPIA AND COLLAPSE

The Western Zhou Chou) (dynasty (1122–771 B.C.) was the first half of the Zhou dynasty of ancient China, which lasted until 221 B.C. The Shang Dynasty (1766-1122 B.C.) was probably conquered by the Western Zhou , which presided over a prosperous feudal agricultural society. Fleeing foreign attack in 771 B.C., the Western Zhou abandoned its capital near Xian and established a new capital farther east at Luoyang (Loyang). The new state, known as the Eastern Zhou dynasty (771–256 B.C.), produced the great Chinese philosophers including Confucius (K'ung Futzu or Kong Fuzi) and the semi-historical figure, Lao Tzu (Lao Zi). [Source: Worldmark Encyclopedia of Nations, Thomson Gale, 2007]

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The philosophers of Classical China looked back upon the centuries following the” Duke of Zhou’s “rule as a utopian era generated by the duke’s virtue. And indeed the period from about 1000 to the late ninth century seems to have been marked by almost uninterrupted domestic peace and the gradual expansion of the Zhou state. During this period of the Western Zhou, strong kings ruled over a united network of hereditary fiefs under the beneficent gaze of Tian. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The strength of the state rested during this period principally on three pillars of political, religious, and social organization. These were the prestige of the Zhou throne; the integrating force of state religion, anchored by the king’s protector-deity, Tian; and the system of clan-based hereditary succession to office or occupation, which became a pervasive feature of feudal society. As the Zhou state matured on the basis of these pillars, it developed an increasingly complex set of formal and informal institutions that came to govern virtually every aspect of the life of the Zhou elite. These institutions, which extended from the offices and ceremonies of court and of religious practice to the etiquette that governed weddings, funerals, banquets, and sporting matches, were known as “"li” (âX), a term that we usually translate as “ritual.” Later thinkers viewed the proliferation of these stylized social forms during the Western Zhou as more than simply a distinguishing characteristic of the time: some saw these regularities as the actual basis of the success of the Western Zhou. /+/

“That success came to a close at the end of the ninth century as a series of domestic insurgencies by regional lords and significant raids by nomad tribes outside the Zhou state weakened the kingship. Instability within the royal family contributed to the disorders, and at least one of the kings of the Western Zhou was driven into exile by dissatisfied parties at the capital. The Classical accounts of these times attributed failures of state to the increasingly debauched character of the successive kings, suggesting that when, in 771, the ultimate 16 collapse arrived, Tian’s apparent limited withdrawal of the Mandate made sense in terms of the decadence of its chosen royal house.” /+/

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see CHINATXT: RESOURCES ON TRADITIONAL CHINA: TRANSLATIONS AND COURSE MATERIALS by Dr. Robert Eno chinatxt.sitehost and scholarworks.iu.edu and and scholarworks.iu.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; ZHOU (CHOU) DYNASTY (1046 B.C. to 256 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; ZHOU RELIGION AND RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; BRONZE, JADE AND CULTURE AND THE ARTS IN THE ZHOU DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; MUSIC DURING THE ZHOU DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; ZHOU WRITING AND LITERATURE: factsanddetails.com; BOOK OF SONGS factsanddetails.com; DUKE OF ZHOU: CONFUCIUS'S HERO factsanddetails.com; EASTERN ZHOU PERIOD (770-221 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; SPRING AND AUTUMN PERIOD OF CHINESE HISTORY (771-453 B.C. ) factsanddetails.com; WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; THREE GREAT 3rd CENTURY B.C. CHINESE LORDS AND THEIR STORIES factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources on Early Chinese History: 1) Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; 2) Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ; 4) Zhou Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Cambridge History of Ancient China" edited by Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy Amazon.com ; “Philosophers of the Warring States: A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy” by Kurtis Hagen and Steve Coutinho Amazon.com ; “Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue: An Annotated Translation of Wu Yue Chunqiu” by Jianjun He Amazon.com; “Zhou History Unearthed: The Bamboo Manuscript Xinian and Early Chinese Historiography” by Yuri Pines Amazon.com ; “Landscape and Power in Early China: The Crisis and Fall of the Western Zhou” 1045-771 BC by Li Feng Amazon.com ; Amazon.com ; “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Ancient China” by Kwang-chih Chang Amazon.com; “The Origins of Chinese Civilization" edited by David N. Keightley Amazon.com; “The Ancestral Landscape: Time, Space, and Community in Late Shang China(ca. 1200-1045 B.C.)” by David N. Keightley Amazon.com, an excellent source on Shang history, society and culture; “A Brief History of Ancient China” by Edward L Shaughnessy Amazon.com; "China: A History (Volume 1): From Neolithic Cultures through the Great Qing Empire, (10,000 BCE - 1799 CE)" Amazon.com ;

Sources on the History of the Western Zhou

Shinji

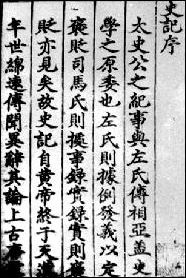

Dr. Eno wrote: “We possess three types of sources for Western Zhou history: textual sources dating from the Classical era, inscriptional sources from Western Zhou ritual bronze vessels, and archaeological reports of excavated Western Zhou sites. The earliest comprehensive account of the founding of the Zhou Dynasty appears in the “Shiji”, or “Records of the Historian,” a history compiled about 100 B.C. by Sima Qian, the imperial historian and astronomer of Emperor Wu of the Han Dynasty. Sima Qian was unable to escape completely from the perspective of legend when writing about the past, which for him was a moral story that revealed complex interplays of heroism and immorality, often in a single individual. Nevertheless, Sima Qian was an independent thinker and judge of character, and if he did not achieve objectivity, he did at least attempt wherever possible to base his information on the best sources available to him. Sometimes he lists his sources for us, and in other cases he is willing to alert us that his account is based on unverifiable hearsay. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“In telling the story of the Zhou royal house, Sima Qian was not looking for men with feet of clay – he accepted the prevailing vision of the founders as ethical giants. Nevertheless, he did his best to create a coherent chronology of the events of the founding, and we can see his account as a comprehensive summation of the great tale that lay behind all the social and political thinking of Classical China. /+/

“The dates of the events that are narrated here, to the degree that they may accurately reflect what occurred, are generally uncertain. The date of the Zhou conquest of the Shang remains a hotly debated point, but the year 1045 B.C. seems increasingly persuasive, and alternative theories now tend to converge very close to this point. The reign of King Wen over the pre-dynastic Zhou lands was a long one; his accession may be dated c. 1100, which would roughly coincide with the accession of the last king of the Shang, whose name, perversely enough, was Zhou – he is referred to here as “Zhòu,” the diacritic mark “ò” distinguishing him from the dynastic house that brought him down.” /+/

Qi (“Prince Millet”)

The legendary, maybe real, origins of the Zhou are traced to Qi (“Prince Millet”). Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “The personal name of Houji (his name means “Prince Millet”) of the Zhou was Qi (“the castaway”). His mother was a member of the Youtai branch lineage of the Jiang clan, and her name was Jiang Yuan. Jiang Yuan was the principal wife of the Emperor Ku. [Source: Shiji 4.111-126 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Jiang Yuan ventured out onto the plains one day, and there she saw the footprint of an enormous man. She felt in her heart a great stirring of pleasure and wished to tread upon it. When she did so, her body was stirred as if with child. A year later a child was indeed born. Because he was viewed as inauspicious, the baby was cast away into a narrow alley, but the horses and oxen who trod past would not step on him. So he was cast away into a deep forest, but people of the mountain woods found him and moved him. So he was cast away onto the ice of a frozen waterway, but flying birds came and sheltered him with their wings and brought him back. Jiang Yuan concluded that a spirit force lay behind all this and so she took him back in and nurtured him. Because she initially wished to cast him away he was named Qi: the castaway. /+/

“When Qi was a youth, he grew very tall, like the mark of the enormous man. In his childhood play, he loved to cultivate plants such as hemp and beans, and his hemp and bean plants flourished. When he grew into an adult he loved ploughing and agriculture. He was skilled at assessing the nature of land and selecting the appropriate grains to plant. The people all imitated what he did. The Emperor Yao heard of him and raised Qi up to be his Chief of Farming. All in the empire benefited and his work was successful. Prince Millet flourished throughout the rule of the houses of Yaotang, Yu, and into the Xia Dynasty. To each age he contributed his splendid virtue. /+/

Dr. Eno wrote: “It was a well established tradition from the early days of Zhou rule, about a thousand years before this account was written, that the grand progenitor or the Zhou clan line was Houji, who is often pictured as the man who taught the Chinese how to cultivate grains. He may be seen as a counterpart of the Spirit-like Farmer, whose similar role as founder of agriculture probably belongs to an alternative mythic tradition. In this opening paragraph, Sima Qian is tying the lineage of the Zhou house to that of the highest of all the sage kings of remote antiquity. The Emperor Ku was the great-grandson of the Yellow Emperor, who for Sima Qian represented the start of history.

The Old Duke

King Wu

The Old Duke was a descendant of Qi, a few generations down the line. Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “The Old Duke, Father Dan revived the enterprise of Prince Millet and Gongliu. He built up his virtue and performed acts of righteousness, and the people of the state stood by him. The Xunyu, a people of the Rong and Di tribes, attacked him, wishing to obtain his stored riches. He willingly gave his riches to them. They attacked again, wishing to obtain his land and its people. The people were all furious and wished to go to battle. The Old Duke said, “Rulers are set up by the people in order to benefit the people. Now the Rong and Ti make war on me on account of my land and people. What difference would it make to the people if they were under me or under another? The people wish to go to war on my behalf, but I could not bear to cause the slaughter of their fathers and sons and then rule over them!” [Source: Shiji 4.111-126 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Thereupon, the Old Duke gathered together his personal retinue and moved away from Bin. He crossed the rivers Tai and Ju, and traveled over Mt. Liang, settling finally at Qixia. And then the entire people of Bin, with the young supporting the aged and parents holding their children, removed en masse to Qixia in order to return to the protection of the Old Duke. When nearby states heard of the humaneness of the Old Duke, many of them too removed to Qixia. Then the Old Duke discarded all the customs of the Rong and Di peoples and ordered the construction of walled cities and private enclosed dwellings. He built walled towns apart from his own. He established the five high ministerial offices and the people all celebrated his virtue in song. /+/

“The eldest son of the Old Duke was named Taibo; the second son was named Yuchong. The consort Taijiang gave birth to the youngest son, Jili. Jili married Tairen. All the wives were most worthy. Tairen gave birth to Chang, and at the time of his birth, the portent of a sage was seen. The Old Duke said, “The flourishing of my house would seem to lie with Chang!” The older sons, Taibo and Yuchong, saw that the Old Duke wished to have Jili as his successor in order that the rulership ultimately be passed to Chang. Thereupon, the two men fled to the lands of the Jing and Man tribes in the south, tattooed their bodies and cut their hair, in order that the throne be passed to Jili.” /+/

Eno wrote: The “vaguely populist notion that the legitimacy of rulers is tied to the interests of the people, is a powerful notion connected with the late Zhou vision of what made the Zhou founders great...The Zhou followed a strict rule of succession: the oldest son always succeeded the father. This text, however, reflects not fact but the historical vision and values of authors from the late Zhou and early Han, and as we shall see, there was among them great interest in the idea of legitimacy through virtue, rather than through blood. This tale, popular in the late Zhou, elegantly blends the two ideals.” /+/

The Old Duke’s order to construct walled cities and private enclosed dwellings “portrays the most significant sorts of transformations: the creation of fully ordered space, physically demarcated by walls, and the introduction of self-perpetuating proto-bureaucratic social organization. These changes are pivotal signs of "sinicization" (acculturation to Chinese norms; also called “sinification”). It is provocative that in this narrative, they follow the success of the Old Duke’s moral accomplishments.” /+/

King Wen, Lord of the West

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “When the Old Duke died, his son Jili succeeded him: he is known as Gongji. Gongji cultivated the Dao of the Old Duke. He was earnest in acts of righteousness, and the patrician lords followed him. When Gongji died, his son Chang succeeded him. He was known in his day as the Lord of the West, and we refer to him as King Wen. [Source: Shiji 4.111-126 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“King Wen followed the course set by Prince Millet and Gongliu and emulated the models set by the Old Duke and Gongji. He was earnest in his humaneness; he honored the elderly; he was caring of the young; he treated worthies in lower positions with ritual courtesy. He attended upon the "shi" (elite men) of the realm with such assiduousness that he took no time to eat all day long, and for this reason the shi allied with him in great numbers. The incorruptible hermits Bo Yi and Shu Qi living in Lone Bamboo heard that the Lord of the West earnestly nurtured elders and said, “Why should we not go to him?” Worthies such as Taidian, Hongyao, San Yisheng, and the grandee Xin Jia all went over to the Lord of the West. /+/

“”The Lord of the West presented to Zhòu the lands west of the River Luo that were in his possession, with the request that in recompense Zhòu abolish the practice of subjecting criminals to the punishment of walking over hot coals. Zhòu agreed to it. The Lord of the West continued to carry out good practices without fanfare, and the patrician lords all came to him to have him mediate their disputes. At this time, there was a legal dispute between the men of Yu and Rui that defied all solution. They took the case to the land of Zhou. Entering within the borders of the Zhou lands, they saw that those who tilled the land all yielded to one another on issues concerning the boundaries of their fields, and the custom of the people was always to yield to their elders. Before they had reached the court of the Lord of the West, the men of Yu and Rui all felt shamed. “The people of Zhou would be ashamed to wrangle as we do. What is the point in going on? We can only humiliate ourselves!” And so they returned home and settled their dispute by yielding to one another. When the patrician lords heard of this, they said, “It would appear that the Lord of the West is destined to receive Heaven’s mandate.” The Lord of the West occupied his throne for about fifty years altogether. When he was a prisoner in Youli, he is said to have fashioned the sixty-four hexagrams of the "Yi jing" from the eight trigrams.

Dr. Eno wrote: “The late Zhou vision of political legitimacy took as a key test the responses of men who had held aloof, at personal cost, from prevalent political corruption. These were men who responded only to virtue and never to personal gain, and legends of the sage kings focus on the moment when their transcending virtue is “recognized” by worthy men who have hidden their talents from the world. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The traditional tales of the evil nature of the last king of the Shang are legion. Generally, he is portrayed as a sex-crazed alcoholic whose greatest delight was disemboweling virtuous ministers, his literary character thus being a perfect foil for the flawless King Wen. While Zhòu’s action here is recounted to show his corrupt character, it is worth noting that throughout Chinese history – some would say until today – legal practice has adhered to the principle that the innocence of a prisoner is chiefly determined by the net worth of bribes offered on his behalf. /+/

King Wu (1045-1043 B.C.)

King Wu

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “When King Wu assumed the throne, he had the Grand Duke Wang as his commander-in-chief and Dan, the Duke of Zhou as his chief of staff. Others, like the Dukes of Shao and Bi, were his advisors. He took the example of King Wen to be his teacher, and he set about to continue his work. [ Eno wrote: “Chinese readers would recognize the high officers of King Wu named here as a roll of great “founding fathers.” The Grand Duke Wang was an aged hermit who had been “discovered” by King Wen (he is a “patron saint” of military masters). The three other dukes were all relatives of King Wu; the Duke of Zhou was his younger brother.] [Source: Shiji 4.111-126 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“King Wu raised his armies. The Grand Duke Wang addressed his troops thus: “Oh, you masses of infantrymen and you who man the oars of our ships! Know that should any of you dally to the battle, he will lose his head!” King Wu crossed the Yellow River. In midstream, a white fish leapt into the royal boat. King Wu stooped to retrieve it and offered it up in sacrifice. Once he had crossed over, a fire cameplummeting down from above and landed by the king’s chamber, where it flowed into a crimson crow which cried with a ghostly sound. And just at this time, eight hundred patrician lords converged upon the Ford of Meng, all by chance, without any prior planning. They all said, “Let Zhòu be attacked!” King Wu replied, “I am not yet certain of the Mandate of Heaven. The time is not yet right.” And he led his troops back home.” /+/

King Wu Battles the Shang and Defeats Them

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “The king abided for two more years. Then he heard that the depravity of Zhòu had reached new depths, that he had killed Prince Bigan and imprisoned Prince Ji. The Master Musician Ci and the Junior Musician Qiang packed up their instruments and fled to Zhou. Thereupon, King Wu issued a proclamation to the patrician lords that read: “The Shang have committed repeated crimes. They cannot but be attacked to the end!” Then, following after his father, King Wen, he led into campaign three hundred war chariots, the Tiger Brave Guard, numbering three thousand, 45,000 armored soldiers, all marching eastward to attack Zhòu. [Source: Shiji 4.111-126 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

In the eleventh year of the reign of King Wu, on the day "wu-wu" in the twelfth month (roughly January) the entire army crossed the Ford of Meng and the patrician lords all convened.’” They said, “Let there be no delay!” King Wu then uttered the “Great Oath,” proclaimed to all the hosts. Now king of the Shang, Zhòu, heeds the words of his wife and cuts himself off from Heaven, destroys the three standards, leaves behind his ancestral fathers and mothers, abolishes the music of his ancestors and creates lascivious music in its stead, thereby altering and bringing chaos to the correct notes of the scale in order to please his wife. Therefore I, Fa, will now reverently execute the punishment of Heaven. Gentlemen, be zealous! Let there be no need for a second or third assault!” /+/

Bronze dagger axes

“The ancients had a saying. ‘The hen does not crow at dawn. When the hen crows at dawn, the household is doomed.’ Now Zhòu, the king of the Shang, heeds only the words of his wife. He discards his ancestors and keeps not to his sacrifices. Benightedly he casts away his house and his state, abandoning the path of his ancestral fathers and mothers. The criminal outcasts of the four quarters he honors and appoints to high office, entrusting them with his missions of state, letting them violently oppress the common folk in the rape of the Shang state! “Now I, Fa, reverently execute the punishment of Heaven. In the affair of this day, go no further than six or seven paces without stopping to regroup – gentlemen, be zealous! Charge no more than four times – five – six – seven – and then regroup. Gentlemen, be zealous! Be awesome – like tigers! Like bears! Like jackals! Like dragons! Here in the suburbs of Shang, do not slaughter those Shang troops who flee, for they will serve us in the west. Gentlemen, be zealous! If you should not be zealous, may you yourselves be slaughtered!” [Eno wrote: “ Sima Qian has taken this entire passage from one of the canonical books of the Confucian tradition, the “Book of Documents”. This section is a chapter known as the “Oath of Mu” (that is, the speech at Muye). When the oath was finished, the patrician lords arranged their four thousand chariots in battle formation on the plain of Muye.”] /+/

“When the Emperor Zhòu learned that King Wu had come, he too called up his troops, numbering 700,000 (!), to repulse the attack of King Wu. King Wu dispatched the Grand Duke Wang with a hundred officers to inspire the troops and detached a corps of cavalry to charge the soldiers of the Emperor Zhòu. Zhòu’s troops, though numerous, possessed no will to fight whatever; it had been their wish that King Wu come as quickly as possible. The armies of Zhòu all reversed their weapons as they engaged in the battle, that the way might be opened for King Wu. And as King Wu galloped through the ranks, the soldiers of Zhòu all collapsed and turned in revolt upon Zhòu himself. /+/

“Zhòu fled back to his palace and mounted to the tower of Deer Pavilion. There he clothed himself in his most precious jewels and, setting himself afire, burned to death. King Wu grasped the great white banner to signal to the patrician lords, and the lords then all bowed low to King Wu. King Wu bowed in return and every one of the lords became his follower. As King Wu approached the city walls of Shang, the people of the city all awaited him outside the wall. Thereupon, King Wu ordered his officers to proclaim to the people of Shang, “Heaven above has sent down its blessing!” And the people of Shang all fell to the ground bowing prostrate with hands clasped. King Wu bowed to them in reply.” /+/

King Wu Establishes the Zhou Dynasty

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “Then King Wu entered the city and went to the place where Zhòu had died. The king himself shot the corpse three times with arrows before descending from his chariot. Then he stabbed it with his sword, grabbed his yellow battle axe and chopped off Zhòu’s head, impaling it on the pole of his white banner. Then he sought out Zhòu’s two favorite concubines; they had already hung themselves. King Wu also shot them three times with arrows, stabbed them with his sword, and, using a black axe, chopped off their heads, impaling them on the poles of smaller white banners. Then King Wu left the city and returned to his troops. [Source: Shiji 4.111-126 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The following day the king performed ceremonies purifying the roads and repaired the state altars of the Shang, together with the Shang palaces. At an appointed time, a hundred officers led the way, riding forth with raised flags. Shuzhen Duo, a younger brother of King Wu, followed leading the battle chariots. Dan, the Duke of Zhou, carried a great battle axe, the Duke of Bi carried a lesser battle axe, and they flanked King Wu. San Yishang, Taidian, and Hongyao formed King Wu’s personal guard, armed with swords. Entering into the city, they took up positions south of the altar of state to the left of the leading warriors, with their retainers all arrayed to their left. Maoshu Zheng offered up the ritual water; Kangshu Feng of Wei laid out the reeds; Shi, Duke of Shao, presented the vegetable offerings; the Grand Duke Wang led forth the sacrificial ox. Yin Yi, the liturgist, spoke. “The last descendant of the Shang, Zhòu, discarded the bright virtue of his forbears, disgraced the spirits by ignoring their sacrifices, and brought benighted violence against the people of the city of Shang. His doings became known to the Heavenly Emperor, the Lord on High.” King Wu then repeatedly bowed prostrate. “The receipt of the great mandate has been shifted away from the Shang. I receive the bright mandate of Heaven.” Again he repeatedly prostrated himself, and then they departed. /+/

“The son of Zhòu, Lufu, was awarded a patrimonial estate within which were settled the remnant people of the Shang. Eno wrote: “The granting of an hereditary estate to Zhòu’s son was an important pious act. Although Zhòu himself was morally discredited, the Zhou founders did not wish to discredit the Shang Dynasty as a whole. Their own legitimacy depended upon their claim that they had received the heavenly mandate that the Shang had once properly held. In setting up Lufu, King Wu was ensuring that the entire line of Shang kings and queens would continue to receive the sacrificial offerings upon which they depended for sustenance – it would be grotesque, in the political and religious culture of the time, to subject the spirits of the former holders of the mandate to starvation. Hence Lufu was established not as the head of a state, per se, but as the leader of a clan lineage and its sacrifices.”

King Wu After the Defeat of the Shang

Zhou Dynasty 1000 BC

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: After King Wu demobilized his troops and returned to the west, “he hunted as he travelled, touring his lands. He recorded matters of governance, composing the text, “Successful Completion of the War.” It was then that he designated the estate lands of the hereditary lords of regions and bestowed upon them sacrificial vessels for use in their lineage temples. He composed the text, “Division of the Vessels and Goods of Yin.” [“Successful Completion of the War” (“Wu cheng”) is the name of a chapter of the “Book of Documents”, the original version of which no longer appears in that text. “Division of the Vessels and Goods of Yin” (“Fen Yin zhi qiwu”) is another lost chapter.] [Source: Shiji 4.126-149 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Thereupon, King Wu, recalling the sage rulers of past eras, rewarded the descendants of the Spirit-like Farmer with estate lands in Jiao, the descendants of the Yellow Emperor with estate lands in Zhu, the descendants of the Emperor Yao with estate lands in Ji, the descendants of the Emperor Shun with estate lands in Chen, the descendants of Great Yu with estate lands in Q.. /+/

“Thereupon, he bestowed estate lands upon his meritorious ministers and gentlemen who had joined in planning the conquest. The first of these to receive an estate was Commander Shangfu (Grand Duke Wang); his estate was to be garrisoned at Yingqiu and named Qi. King Wu bestowed his younger brother Dan, the Duke of Zhou, with an estate to be garrisoned at Qufu and named Lu. He bestowed [his cousin] Shi, the Duke of Shao, with an estate in Yan, his younger brother Shuxian with an estate in Guan, and his younger brother Shudu with an estate in Cai. Others received estates according to their status. [Eno wrote: “These grants of estates (which have traditionally been referred to as “fiefs”), represent the establishment of the Zhou political model. Only a small capital region of the broad Zhou state was administered directly by the ruling king. Control of outlying regions was entrusted to close relatives and allies and their descendants, who ruled territorial estate lands by hereditary right from bases in militarized fortress cities.] /+/

King Wu Lays Out His Plan for the Zhou Dynasty

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: ““Summoning in assembly of the rulers of the lands in all the nine regions, King Wu ascended the hills at Bin in order to gaze back toward the capital region of the Shang. As King Wu continued his return toward the homeland of Zhou, he was unable to sleep at night. The Duke of Zhou visited the King in his residence and asked, “Why have you been unable to sleep?” “I will tell you,” said the King. “From a time before I was born until the present, a period of sixty years, Heaven received no sacrificial offerings from Yin. In consequence, wild deer roamed in all the pastures and insect pests infested the fields. It was because Heaven received no sacrifices from Yin that our success today has come about. It was Heaven that established the House of Yin: in its time, the Yin promoted 360 famous men, yet never ruled with brilliance – yet until this time neither was it destroyed. And I have not even yet secured the protection of Heaven. Where would I have the leisure to sleep? [Source: Shiji 4.126-149 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“To secure Heaven’s protection and be secure in Heaven’s House we must thoroughly seek out those who are wicked and remove them as we have done with the Yin king Zhòu. We must strive day and night to comfort and draw the allegiance of the people, and so secure us in our western lands. We must gain their willing submission through brilliant rule that shines with the brightness of our virtue. “From the bend of the River Luo to the bend of the River Yi the land is level and the people dwell in ease. This was the homeland of the House of Xia. In that place, we would gaze south to Mount Santu and north to the slopes of Yue Peak; if we looked behind us we see the Yellow River, ahead would be the courses of the Rivers Luo and Yi. Thus we would not be distant from Heaven’s House.”Only after King Wu had laid out a plan for the Zhou to dwell at the city of Luo did he finally return home. Then he released his horses on the south slopes of the Hua Mountains and let loose his cattle on the plains of Taolin. He put aside his axe and shield, stored away his weapons and released his troops, and so manifest to the world that he would employ the tools of war no more. /+/

Eno wrote: The bends of the Rivers Luo and Yi “section depicts King Wu as the first to plan the founding of a second Zhou capital city in the centrally located plain between the Luo and Yi Rivers – site of the future Luoyang. The second capital was ultimately located near to Mt. Song, which was sometimes pictured as the central mountain of the realm and the axis mundi – the pivot of the world. Mt. Song was sometimes referred to as Heaven’s House ("tian shi"), and that phrase seems to be used in this text both to mean the broad kingdom that had been under the sway of the Shang and the mountain at its center, which would be an ideal seat of Zhou power, as it supposedly had been long before for the Xia kings. /+/

King Cheng (1042-1006 B.C.)

King Cheng

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “When King Cheng was young, the Zhou had just brought order to the empire. The Duke of Zhou was afraid that the patrician lords would rebel against the Zhou and so he assumed the powers of a regent to administer the state. Guan Shu and Cai Shu, together with others of the brothers of the late King Wu, rose up in rebellion against the Zhou under the standard of Wu-, the son of the last Shang king Zhòu. [Source: Shiji 4.126-149 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The Duke of Zhou assumed the powers of King Cheng and launched a campaign which led to the deaths of Wu-and Guan Shu, and to the banishment of Cai Shu. He installed Weizi Kai, a prince of Yin, as the clan leader of the Yin lineage and gave him a patrimonial estate in Sung. Then he rounded up many of the remnant people of Yin and presented them to his youngest brother Feng, who became the ruler of the land of Wey under the title Kang Shu.... /+/

“The Duke of Zhou occupied the office of regent for seven years. When King Cheng came of age, the Duke of Zhou returned to him the reins of government and faced north at court in the position of a minister. King Cheng resided in the royal precincts of Feng and ordered the Duke of Shao to erect walls of encampment once more at the city by the River Lo, as his father King Wu had intended. The Duke of Zhou once again divined and surveyed the site, and saw the construction work through to its finish, settling the nine royal cauldrons in that city. “This is the center of the empire,” he said. “When the lands of the four quarters submit tribute, their routes to this place will all be balanced in distance”... /+/

“The Duke of Shao served as the Lord Protector and the Duke of Zhou became General-in-Chief. He went east to attack the Yi-tribes of the Huai River Valley. When the Duke of Zhou returned, he composed the “Institutes of the Zhou,” which established and rectified ritual and music. The regulations of administration were thereupon reformed. The people lived in harmony and the sounds of odes of praise rose up. /+/After the Yi-tribes of the east had been subdued by King Cheng, Xi Shen sent gifts. These the king presented to Elder Rong.... /+/

“When King Cheng lay dying, he feared that the heir apparent, Prince Zhao, was not worthy of the throne. He ordered the Duke of Shao and the Duke of Bi to lead the patrician lords in ministering to the prince and establishing him upon the throne. After King Cheng died, the two dukes did lead the patrician lords in presenting Prince Zhao at the royal ancestral temple. There they instructed the prince in the arduous nature of the kingly enterprise to which King Wen and King Wu had devoted themselves. The explained that great stress must be laid upon thrift in government and that the king must not possess many desires, in order that he may approach his tasks with reverence and faithfulness. Then they composed for him the document “The Departing Mandate.”

King Kang (1005-978 B.C.) And King Zhao (977-957 B.C.)

King Kang

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “Prince Zhao was subsequently enthroned as King Kang. Once King Kang ascended the throne, he issued a proclamation to all the patrician lords proclaiming the enterprise of Wen and Wu in order to extend it; this was the “Announcement of Kang.” In this way, during the reigns of Kings Cheng and Kang, the empire was at peace and for over forty years, there was no cause to employ corporal punishment. King Kang ordered the Recorder, the Duke of Bi, to separate the residential areas of the people and create a suburban site near the capital city of Zhou; this was the “Order to Bi.” [Source: Shiji 4.126-149 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“When King Kang died, his son Xia, known as King Zhao, succeeded him. During the reign of King Zhao, the kingly Dao grew obscure. King Zhao traveled south to tour and hunt, and he did not return. He died on the north bank of the Yangzi River. No messenger was sent to court to report his death because they did not wish to speak of the circumstances.” /+/

Eno wrote: There are a number of interesting accounts of King Zhao’s demise, which is one of the more puzzling events of the early Zhou. One text, the "Generational Annals of the Emperors and Kings", reports thus: “The virtue of King Zhao declined. He campaigned in the South and crossed the River Han. The boatmen disliked him and provided him with a boat of hardened mud. When the king had sailed the boat the middle of the stream, the boat became wet through and dissolved. The king together with the Duke of Cai drowned in the water. His aide Xin Youmi possessed long arms and great strength. He swam out and retrieved the king’s body. The people of Zhou would not speak of these events.” /+/

The “Bamboo Annals” story differs. “In the sixteenth year of his reign, King Zhao attacked the people of Chu. Crossing the River Han, he encountered a large rhinoceros. In the nineteenth year, in the Spring, a light of many colors was observed penetrating the ‘Purple Palace’ region at the pole of the night time sky. When the Duke of Cai and the Earl of Xin accompanied the king in [another] attack upon Chu, the sky grew dark and birds and rabbits trembled. All six divisions of the royal army were lost in the River Han and the king died.” /+/

King Mu (956-923 B.C.)

King Mu (Mu Wang, 956-923 B.C.) was a West Chou king and the earliest reputed Silk Road traveller. His travel account Mu tianzi zhuan, written in the 5th-4th century BC, is the first known travel book on the Silk Road. It tells of his journey to the Tarim basin, the Pamir mountains and further into today's Iran region, where the legendary meeting with Xiwangmu was taken place. Returned via the Southern route. The book no longer exists but is referenced in Shan Hai Zin, Leizi: Mu Wang Zhuan, and Shiji. [Source: Silkroad Foundation silk-road.com |*|]

King Mu reigned 55 years and is said to have died at age 105. Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “Man, the son of King Zhao, was enthroned: this was King Mu. King Mu was already fifty at the time he came to the throne, and the kingly way had decayed. King Mu regretted that the way of Kings Wen and Wu had disappeared, and be ordered that Bojiong assume the position of Grand Ostler, admonishing him with the “Order to Jiong.” Peace was thus restored. [Source: Shiji 4.126-149 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

King Mu’s greatest enemy was the Dog Nomads, who eventually, in 771 B.C., overran the Zhou capital, killed the king, and brought the Western Zhou to an end. According to the judgement of a 5th century B.C. who wrote in the following passage it was King Mu’s failings that planted the seeds of the later disaster: “King Mu prepared to launch a campaign against the Dog Nomads. Moufu, Duke of Cai, admonished him saying, “This may not be. The former kings made their virtue bright and did not need to make a show of their arms. Weaponry should be husbanded and mobilized in the proper season. If it is mobilized thus it will inspire awe, but to make a show of troops is to play with them, and if one plays with them they will have no power to inspire fear. For this reason, the ode of the Old Duke says, Assemble our spears and halberds,/ fill our sheaths with bows and arrows./ Our quest is for excellent virtue, / we lay it forth in this grand music:/ Truly, may our kings preserve this!” /+/

“The way the former kings treated the people was to encourage them to set right their virtue and deepen their natural sentiments, to make goods that they desired ample and ensure that their material needs were met. They made clear what benefited and what harmed the state and ornamented these distinctions by means of patterns. Thus they encouraged the people to apply themselves to what was beneficial and avoid that which was harmful, to cherish virtue and fear the awesome. Hence they were able to protect their generations and amplify their grandeur. /+/

Western Zhou states

King Mu and the Laws of the Former Kings

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: King Wu said: “According to the regulations of the former kings, the lands within the estates of Zhou are the Capital Regions, the lands beyond are the Patrician Estates. The outer marches guarded by the lords and the garrison commanders constitute the Regions of Guests; the lands of the Yi-tribes in the East and the Man-tribes in the South constitute the Attached Regions; the lands of the Rong-nomads and the Di-nomads constitute the Wasteland Regions. Within the Capital Regions, there should be contributions to the daily sacrifices; within the regions of the Patrician Estates there should be contributions to the monthly sacrifices; within the Regions of Guests there should be contributions to the seasonal sacrifices; within the Attached Regions there should be annual tribute sent; within the Wasteland Regions there should come word that the Zhou ruler is ever acknowledged as king. /+/

““The rule of sacrifice of the former kings was this: If offerings for daily sacrifices are omitted by those within the Capital Regions, cultivate one’s intent; if offerings for the monthly sacrifices are omitted within the Patrician Estates, cultivate one’s speech; if offerings for the seasonal sacrifices are omitted in the Regions of Guests, cultivate social patterns; if annual tribute fails to come from the Attached Regions, cultivate reputation; if acknowledgment of kingship fails to come from the Wasteland Region, cultivate virtue. Only if all these steps have been followed completely, then, if still none come from such a region, cultivate punishments. Then you may corporally punish those who do not contribute to the daily sacrifice, attack those who do not contribute to the monthly sacrifice, campaign against those who do not contribute to the seasonal sacrifice, admonish those who do not send annual tribute, and report their failings to those who do not acknowledge the kingship of the Zhou. /+/

““Thus do you have penalties for corporal punishment, weaponry for attack, preparations for campaigns, ordinances of awesome admonishment, and the rhetoric of official notification. If these ordinances have been applied and the appropriate words sent and still there is no response, then you must further cultivate your virtue, not send the people off to distant places. In this way, there will among those near be none who does not obey, and among those afar, none who does not submit. /+/

““Now, since the close of the time of the chieftains Great Bi and Boshi, the tribe of the Dog Nomads has sent acknowledgment of the Zhou’s kingship according to their proper office. If you, the Son of Heaven, were to say, ‘They do not send offerings for the seasonal sacrifices, this I will make a show of military might,’ you will be casting away the teachings of the former kings. Will you not then be in danger of defeat? I have heard that the Dog Nomads have established patterns of sincerity and, according with the old virtue, they preserve to the utmost the pure and natural. They have means whereby to resist us!”But the king campaigned against them. He returned having captured four white wolves and four white deer. From this time forth, envoys from the Wasteland Regions no longer appeared at the Zhou court. [Eno wrote: “Here, the account reproduces an entire chapter of the “Book of Documents”. The point is to show that in response to unharmonious behavior among the patrician lords, King Mu resorted to a system of laws and punishments. The text, “Punishments of Lü,” may be found in Clae Waltham’s edition of James Legge’s translation of the “Book of Documents” ("Shu Ching", “The Marquis of Lü on Punishments”).] /+/

Tyranny of King Li (859-842 B.C.)

King Xuan

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “The conduct of the king grew increasingly despotic and lavish. The people of the capital began to revile him. The Duke of Shao admonished the king, “The people cannot bear your rule.” The king was furious. He employed a shaman from the land of Wey and had him use his special sight to identify those who spoke against him. Whoever the shaman reported the king executed. Soon, the clamor of the people subsided. The patrician lords ceased to come to court. [Source: Shiji 4.126-149 by Sima Qian, via Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“By the thirty-fourth year of his reign, the king had become even more tyrannical. The people of the capital dared not speak; they looked at one another as they passed on the roads. King Li was delighted. He told the Duke of Shao about it. “I was able to put a stop to the slander! They don’t dare speak now.” “You have blocked it,” replied the duke. “But to dam the mouths of the people is more dangerous than a dike by a river. When a river that has been blocked up breaks through its dikes there are always many who are hurt, and it is like this with the people. That is why those who know how to manage the waters dredge the rivers so as to guide their proper flow; those who know how to manage the people, proclaim encouragements so that they will speak. /+/

““The government of a Son of Heaven calls for all those from the ranks of high ministers to the to express themselves through poems; it calls on blind musicians to offer songs, scribes to offer documents, generals to offer cautions, the blind to offer rhapsodies and chants, artisans to offer admonishments, and commoners to pass along their remarks. Courtiers must exhaustively correct the king, his clansmen must investigate his governance thoroughly, court musicians and scribes must instruct him and the elders must elaborate on their instruction. And after all this, the king reflects on all he has learned. That is why his affairs proceed without obstruction. /+/

““The possession of mouths by the people is like the possession of rivers and mountains by the earth: it is the font from which riches flow, the fertile fields and the plains from which food and clothing are born. It is through the words that are released from their mouths that good government or failure arises. To enact what is good and defend against what brings failure is to give birth to riches, food, and clothing. /+/

““The people conceive of things in their minds and give vent to them through their mouths; when their thoughts are complete they may be put into practice. If you block up their mouths, what will come of it!”The king paid no heed. The kingdom continued on with the people afraid to speak for three years more. Then the people revolted and attacked King Li. The king fled to the city of Zhi. /+/

“King Li’s heir apparent, Prince Jing, hid in the household of the Duke of Shao. When the people of the capital heard this, they surrounded the duke’s compound. The duke said, “In the past, I admonished the king urgently and he paid no heed, so we have come to these difficult times. If I allow them to kill the prince the king will look upon me with fury as his enemy. A minister who serves his lord endures danger and does not inspire fury as an enemy; he may have cause for complaint, but he himself is never angry – and how much more must this be true of one who serves a king!” Thereupon he sent his own son out as a substitute for the prince, and in this way, the prince was able to escape. /+/

King You (781-771 B.C.) And the Collapse of the Western Zhou

Royal Zhao chariot pit

Sima Qian wrote in “The Shinji”: “ King Xuan was succeeded by his son Gongnie, who ruled as King You. In the second year of King You’s reign, a great earthquake shook the three great rivers of the western regions of Zhou. Bo Yangfu said, “The Zhou is coming to an end! The of heaven and earth is never disorderly. If it exceeds its proper degree, it is the people who introduce chaos to it. Earthquakes occur when the yang force is suppressed and cannot arise from the earth, and the yin force is contained and cannot disperse upwards. This quake of the three rivers is due to the fact that yang has left its due position and is pressing down upon yin. The springs of the rivers are surely blocked, and when the springs are blocked the state will surely perish. /+/

““When the water and the soil spread out they are employed by the people, but when they cannot spread the people are without the means to fill their needs; what use is there in hoping that the state will not perish? “It was this way when the Rivers Yi and Luo dried up and the Xia state came to its end, and when the Yellow River dried up and the Shang came to its end. Now the virtue of the Zhou resembles the last days of these two dynasties. And the springs of the rivers have become blocked, and being so, the rivers surely will dry up. /+/

““A state depends upon its mountains and rivers; if the mountains tumble and the rivers run dry, these are the omens of a state’s end. And once the rivers run dry, the mountains will surely fall. In this way, the extinction of the state cannot be further than ten years off, for ten is the cycle of the numbers. The state which Heaven means to cast aside cannot exceed its cycle.” That year, the three rivers ran dry and Mount Qi tumbled. /+/

“In the third year of his reign, King You became infatuated with his consort Bao Si. Bao Si gave birth to a son who was named Bofu. King You wished to remove the heir apparent. The mother of the heir was a daughter of the Marquis of Shen and had married as King You’s queen. King You had later received Bao Si and, loving her, desired to discard the queen along with the heir, Prince Yijiu, and appoint Bao Si as queen and Bofu as heir. The grand historian of the Zhou, Boyang, consulted the historical records and said, “The Zhou will certainly perish!” In the past, at the time that the Xia Dynasty had entered its decline, two spirit-like dragons had descended to the king’s court and spoken saying, “We are the two lords of Bao.”[This Bao is the surname of Bao Si.] The Xia king divined about killing the dragons, removing them, and allowing them to remain. None of these divinations was auspicious. Then he divined concerning capturing their saliva and storing it. This divination was auspicious. Thereupon, the king had commanded that a formal investiture ceremony be mounted in which the dragons were presented with cloth and valuables of office and told of the divination. This being done, the dragons flew off, leaving their saliva, which was collected in a box and stored away. /+/

Royal Zhou chariot pits

“When the Xia fell, this box was passed to the Shang, and when the Shang fell, this box was passed to the Zhou, and in all this time of the three dynasties, none dared to open the box. At the close of King Li’s reign, however, the box had been opened and the saliva had flowed through the court. No one could get rid of it. King Li had then ordered one of the court woman to strip naked and call the saliva. When she did so, the saliva turned into a black tortoise, which carried the woman off into the women’s chambers at the rear of the palace. In the women’s chambers the turtle was encountered by a servant girl who had only recently lost her first teeth. She became pregnant then and gave birth to a daughter afterwards. Having no husband, she cast the child away in fear. /+/

“During the time of King Xuan, there came to be a song sung by young girls that went: A bow of mountain mulberry, / a sheath of wood from the tree:/ Surely the state of Zhou shall perish! The king learned that there was a husband and wife who were attempting to sell a bow and sheath of this description. He ordered that the couple should be caught and executed. They fled, and wandering on the road they encountered the child that had formerly been discarded by the servant girl. Hearing her sobs at night they pitied her and took her along with them on their escape. They fled to the state of Bao. /+/

“In Bao, this child was received by a courtier who had committed a crime and presented to the ruler of Bao in order that the courtier’s offense be pardoned. Later, the child was presented by the ruling clan of Bao to the king under the name Bao Si. In the third year of his reign, King You saw Bao Si in his inner chambers and was infatuated with her. She bore him the son Bofu and, in the end, the king did indeed cast away his queen of the Shen clan and her son, his heir, and appoint Bao Si as queen and Bofu as the heir apparent. /+/

““The calamity has come!” sighed the grand historian Boyang. “There is nothing that can now be done.”Bao Si did not like to smile. King You tried ten thousand ways of making her smile, but none succeeded. Finally King You ordered that the beacon fires that were the signal for the patrician lords to come save Zhou from an enemy attack should be lit and great drums sounded. The patrician lords all came rushing, but there was no enemy to fight. Thereupon Bao Si burst into gales of laughter. King You was delighted, and thereafter would frequently light these fires. Eventually, the lords ceased to believe that the alarm was genuine, and fewer and fewer responded. /+/

“King You employed Shifu of the state of Guo as his Minister-in-Chief and gave him charge of all administration. The people of the capital were all resentful of this. Shifu was glib and clever, expert at flattery and fond of wealth. The Marquis of Shen was furious that his daughter and her son had been deprived of their roles as queen and heir apparent. He allied with the state of Zeng and the western tribes of Dog Nomads and their troops attacked the king. King You ordered that the beacon fires be lit to assemble the patrician armies, but no troops responded to the fires. In the end, King You was killed at the foot of Mount Li and Bao Si taken prisoner. The invading troops sacked the capital city of Zhou and then left. The patrician lords thereupon joined with the Marquis of Shen and set upon the throne Yijiu, the original heir apparent, who reigned as King Ping and carried on the sacrifices to the Zhou ancestors. Upon his enthronement, the court was removed eastward to the city of Luo in order to avoid the threat of the nomad tribes.” /+/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, University of Washington

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021