WARRING STATES PERIOD (453-221 B.C.)

Zhou-era chariot The last stage of the Zhou Dynasty was called the Warring States Period. It was characterized by a state of near perpetual war between a half dozen warring states that vied for control of China. The war persisted for 500 years until the warring states collapsed and China was united under Emperor Qin in 221 B.C. The Warring States Period was marked by violence, political uncertainty, social upheaval, a lack of powerful central leaders and an intellectual rebellion among scribes and scholars that gave birth to a golden age of literature and poetry as well as philosophy. Great works of art from the Warring States Period include bronze vessels with inlaid geometric silver decorations, snake-shaped bronze fittings, jade and gold wire jewelry and bows made with dragons with glass eyeballs.

The Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) was a time of turmoil and violence, with constant warfare between the regional states, but it was also a time of great intellectual and artistic activity, when the intellectual traditions of Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism originated. Dr. Robert Eno of Indian University wrote: “The Warring States period resembles the Spring and Autumn period in many ways. The multi-state structure of the Chinese cultural sphere continued as before, and most of the major states of the earlier period continued to play key roles. Warfare, as the name of the period implies, continued to be endemic, and the historical chronicles continue to read as a bewildering list of armed conflicts and shifting alliances. In fact, however, the Warring States period was one of dramatic social and political changes. /+/

“The fast growing need for skilled men able to administer the vastly more complex military and political demands of the Warring States period created a lively demand for men of intellectual talent. Whereas the most prized skills of the Spring and Autumn period had been the charioteering skills and ritualized etiquette of the patrician born – abilities that could be drilled into any young man – the Warring States prized the ability to devise clever and original strategies of war, or of economic and diplomatic policy. Raw intelligence and learning which was often derived through study of books or with an expert teacher were now the qualities most prized; whatever their virtues of bravery, bearing, and clan loyalty, the patrician class held no monopoly on intelligence, and, in time, little advantage with regard to learning as well. Consequently, the Warring States was a time of sharply increasing social mobility. Positions of power gradually shifted into the hands of men of wit, many of whom were of low birth or sons of very junior branches of the shi class. Along with changes in agricultural technology and commerce, these factors made the Warring States both the bloodiest and most dynamic era of Chinese history.” /+/

For the complete article from which this much of the material here is derived see CHINATXT: RESOURCES ON TRADITIONAL CHINA: TRANSLATIONS AND COURSE MATERIALS by Dr. Robert Eno chinatxt.sitehost and scholarworks.iu.edu and /scholarworks.iu.edu

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: ZHOU, QIN AND HAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; ZHOU (CHOU) DYNASTY (1046 B.C. to 256 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; ZHOU RELIGION AND RITUAL LIFE factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; ZHOU DYNASTY SOCIETY factsanddetails.com; BRONZE, JADE AND CULTURE AND THE ARTS IN THE ZHOU DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; MUSIC DURING THE ZHOU DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; ZHOU WRITING AND LITERATURE: factsanddetails.com; BOOK OF SONGS factsanddetails.com; DUKE OF ZHOU: CONFUCIUS'S HERO factsanddetails.com; HISTORY OF THE WESTERN ZHOU AND ITS KINGS factsanddetails.com; EASTERN ZHOU PERIOD (770-221 B.C.) factsanddetails.com; SPRING AND AUTUMN PERIOD OF CHINESE HISTORY (771-453 B.C. ) factsanddetails.com; THREE GREAT 3rd CENTURY B.C. CHINESE LORDS AND THEIR STORIES factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources on Early Chinese History: 1) Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu; 2) Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ; 4) Zhou Dynasty Wikipedia Wikipedia ;

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Cambridge History of Ancient China" edited by Michael Loewe and Edward Shaughnessy Amazon.com ; “Philosophers of the Warring States: A Sourcebook in Chinese Philosophy” by Kurtis Hagen and Steve Coutinho Amazon.com ; “Spring and Autumn Annals of Wu and Yue: An Annotated Translation of Wu Yue Chunqiu” by Jianjun He Amazon.com; “Zhou History Unearthed: The Bamboo Manuscript Xinian and Early Chinese Historiography” by Yuri Pines Amazon.com ; “Landscape and Power in Early China: The Crisis and Fall of the Western Zhou” 1045-771 BC by Li Feng Amazon.com ; Amazon.com ; “A Companion to Chinese Archaeology” by Anne P. Underhill Amazon.com; “The Archaeology of Ancient China” by Kwang-chih Chang Amazon.com; “A Brief History of Ancient China” by Edward L Shaughnessy Amazon.com; "China: A History (Volume 1): From Neolithic Cultures through the Great Qing Empire, (10,000 BCE - 1799 CE)" Amazon.com ;

Sources and Books on the Warring States Period

Ancient Chinese chariot

The Warring States era is named after a text, the "Zhanguo ce", or "Intrigues of the Warring States", an extensive collection of anecdotes recounting the backgrounds and consequences of court speeches delivered by ministers or visiting "shi" to rulers of the various states. These anecdotes provide us with very detailed accounts of the political events of the period from the mid-fifth to late third centuries B.C. The text served as a basis for much of the narrative of the Warring States period that Sima Qian included in his “Shiji”. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Because it is relatively long, complex and influential, the Warring State era is often divided into a number of periods. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: ““However, the chaotic political situation of the Warring States era does not lend itself readily to simple periodization.” Some periods “overlap substantially” and “are distinguished less by their dates than by the themes we will draw from them. Likewise, largely because there exists no Warring States literary equivalent to the Zuo commentary to the “Spring and Autumn Annals”, the period is not as rich in extended narrative accounts. For this reason, there are fewer of these here, and they are confined to the latter part of the narrative.” /+/

Eno divides the Warring State Perion into four narratives: Period I: Structures of Social Mobility 453-380 B.C.; Period II: Reforms in Qin 360-338 B.C.; Period III: The Horizontal and Vertical Alliances 320-256 B.C.; Period IV: The Great Ministerial Lords of the Third Century 300-230 B.C.; Epilogue: The Final Conquest of the Qin The birth of philosophical thought in China took place during a period when political and social structures that had been long established were subject to acute stress.

No primary text provides the type of detailed narrative of Warring States political history that we find for the Spring and Autumn period in the “Zuo zhuan”. The closest comparable text is a book called the “Zhanguo ce”, or “Intrigues of the Warring States”, which consists largely of collected speeches of political advisors of the period. A fine summary overview of the Warring States period is provided in the “Cambridge History of Ancient China”(Cambridge: 1999) by Mark Lewis, in his chapter, “Warring State, Political History” (pp. 587-650). Maspero’s “China in Antiquity”, also includes a good account. Hsu Cho-yun’s book “Ancient China in Transition”, also noted earlier as an important work for understanding the social dynamic of the entire Eastern Zhou era, is particularly useful in its discussions of social, political, and economic changes that transformed China during the Warring States era. Some of Hsu’s important ideas are challenged in interesting ways by Mark Lewis in his “Sanctioned Violence in Ancient China”(Albany: 1990)

Eastern Zhou, Spring and Autumn and Warring States Periods

Beginning in the 8th century B.C. the authority of the emperors degenerated and hundreds of warlords fought among themselves until seven major kingdoms prevailed. This led to the formulation of the Eastern Zhou Dynasty (770-221 B.C.). The Spring and Autumn period (771-482 B.C.), the Warring States period (481-221 B.C.) and the Age of Philosophers and the China’s Classical Age (6th century to 3rd century B.C.) occurred within the Eastern Zhou Dynasty.

The Spring and Autumn (722 to 476 B.C.) and Warring States (476 to 221 B.C.) periods though marked by disunity and civil strife, witnessed an unprecedented era of cultural prosperity — the "golden age" of China. The atmosphere of reform and new ideas was attributed to the struggle for survival among warring regional lords who competed in building strong and loyal armies and in increasing economic production to ensure a broader base for tax collection. To effect these economic, military, and cultural developments, the regional lords needed ever-increasing numbers of skilled, literate officials and teachers, the recruitment of whom was based on merit. [Source: The Library of Congress *]

Zhou chariot fitting

Also during this time, commerce was stimulated through the introduction of coinage and technological improvements. Iron came into general use, making possible not only the forging of weapons of war but also the manufacture of farm implements. Public works on a grand scale — such as flood control, irrigation projects, and canal digging — were executed. Enormous walls were built around cities and along the broad stretches of the northern frontier. *

Historian Francis Fukuyama of Johns Hopkins wrote: “As a result of the 500 years of intensive warfare that occurred during the Spring and Autumn and Warring States period (the eastern Zhou dynasty, 711-211 B.C.), Chinese states formed and began to consolidate into a smaller number of larger polities. As a result of the desperate need to mobilize resources for war, they developed bureaucratic administrations that relied increasingly on impersonal administration rather than patrimonial recruitment that as typical of earlier periods of Chinese history."

Dr. Eno wrote: “China’s Classical age was a tumultuous era, filled with the dangers of constant civil war, political disruptions, and unpredictable social change. The intellectual elite of that period, who are the authors of all the textual records of that time, were anxious to search the past looking for political and ethical models that could help them extricate society from this era of crisis and chaos. The human past was for them as promising a field of study as the world of the natural sciences much later became for the West. At the same time, there was an urgent desire to make out a glimpse of the future, an almost millennial urge to see a new age of order emerge. These interests in history and the millennium were connected because the literate elite looked to the past as the key to their future. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

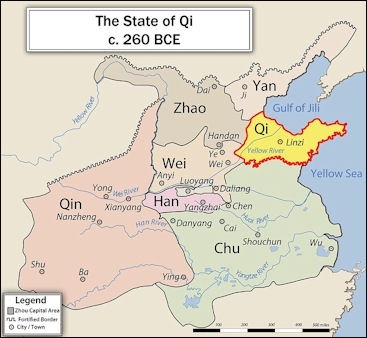

Warring States: Jun, Qin, Qi and Chu

Of the four great Spring and Autumn powers — 1) Jin, 2) Qin (Central States), 3) Qi and 4) Chu— Qi, Chu, and Qin survived into the Warring States Period. Jin had been divided into three states of Han, Zhao and Wei, sometimes collectively referred to as the "Three Jins". Of the two late-arising powers of the Spring and Autumn, Wu and Yue, the former had been snuffed out in 476 B.C., while the latter was no longer a significance player after the death of King Goujian in 465 B.C. The state of Yan, north of Qi, although ranked considerably below its greater rivals, is sometimes counted as a seventh powerful state competing for dominance. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The Warring States Period (475-221 B.C.) was a time of turmoil and violence, with constant warfare between the regional states, but it was also a time of great intellectual and artistic activity, when the intellectual traditions of Confucianism, Daoism, and Legalism originated. As military conflict became more frequent and more deadly, one by one the smaller states were conquered and absorbed by the half dozen largest ones. One of the more successful such states was Chu, based in the middle reaches of the Yangzi River. It defeated and absorbed fifty or more small states, eventually controlling a territory as extensive as the Shang or Western Zhou dynasties at their heights. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

During the fourth century B.C., the balance of power was delicate enough that it shifted with great frequency. Qin, Qi, and Chu remained the greatest of the states, but the “three Jin” – that is, Han, Wei, and Zhao, the states into which Jin had dissolved – played important roles. In fact, during the middle years of the century, Wei actually held so much power and was so centrally located that it seemed nearly preeminent among the states. By the close of the century, however, Qin was clearly gaining the dominance that would eventually bring it to absolute power. /+/

Usurpation in Qi

bronze bow device for controlling chariots

Of the main Warring States powers, the one that underwent the greatest change during the fifth century, was Qi. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ Now that Jin was gone, Qi was the major state with the greatest claim to legitimacy in the Zhou cultural sphere. Qin and Chu were relative newcomers to China. Their ruling houses had emerged only late in the Western Zhou or during the first decades of the Spring and Autumn period. Qi, however, had been founded as the patrimonial estate of the Grand Duke Wang, the general-in-chief of King Wu during the conquest of the Shang. Although the Grand Duke was not a member of the Zhou royal lineage, his clan of Jiang was honored through his accomplishments and its prestige had been renewed by the greatness of Duke Huan during the seventh century. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“By the fifth century, however, the quality and power of the Jiang house had declined in Qi, and a situation had emerged similar to those in Jin and Lu, where great families rather than the duke’s clan held the balance of power. In the case of Qi, however, the outcome of the struggle for power was different, and of a distinct benefit to the state. /+/

“During the hegemony of Duke Huan, he had sheltered at court a princely refugee from a neighboring state. This man’s descendants settled permanently in Qi, and the prestige of their lineage, together with an apparent family tendency towards ambition, soon brought their lineage, the Tian clan, into competition with other great patrician clans native to Qi. /+/

“As in other states, over the centuries the power of the great clans came to overawe the dukes in Qi, and it may have appeared as if Qi would follow the path of the three clans of Jin, who had carved new states from a great power. But in the case of Qi, successive generations of talented men from the Tian family proved increasingly indispensable to the rulers of Qi. By the middle of the fifth century, the Tians dominated the state to such a degree that they planned the usurpation of both power and title. Launching successful attacks on their greatest competitors, the Tian clan managed first to achieve a full monopoly of political control as ministers to the duke, then to divide the territory of Qi, taking half for their direct control and leaving half to their puppet ruler, then transporting the ruler himself to an obscure seaside town (391). Finally in B.C. 386, after the last legitimate ruler of Qi died without a son in his lonely outpost, the leader of the Tians obtained recognition from the Zhou king as the hereditary ruler of Qi, succeeding to the rights of the Grand Duke Wang. /+/

“Upsetting as this process may have been to those remaining loyal to the Zhou system of hereditary privilege, the accession of a vigorous new clan to the leadership of Qi prevented that state from either disintegrating or being overwhelmed by growing military threats from other powers. The shift of the ducal mandate of a great power to an ambitious émigré lineage exemplified the flexibility which had come to the notion of hereditary privilege. It is no accident that thereafter in the state of Qi, the dukes followed a policy of actively courting talented men to come to Qi from other states, rewarding them with high office if their abilities met the needs of the ruler.

States in the Warring States Period

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: ““The period following that of the Zhou dictatorships is known as that of the Warring States Period. Out of over a thousand states, fourteen remained, of which, in the period that now followed, one after another disappeared, until only one remained. This period is the fullest, or one of the fullest, of strife in all Chinese history. The various feudal states had lost all sense of allegiance to the ruler, and acted in entire independence. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Warring States China

It is a pure fiction to speak of a Chinese State in this period; the emperor had no more power than the ruler of the Holy Roman Empire in the late medieval period of Europe, and the so-called "feudal states" of China can be directly compared with the developing national states of Europe. A comparison of this period with late medieval Europe is, indeed, of highest interest. If we adopt a political system of periodization, we might say that around 500 B.C. the unified feudal state of the first period of Antiquity came to an end and the second, a period of the national states began, although formally, the feudal system continued and the national states still retained many feudal traits. As none of these states was strong enough to control and subjugate the rest, alliances were formed. The most favoured union was the north-south axis; it struggled against an east-west league. The alliances were not stable but broke up again and again through bribery or intrigue, which produced new combinations. We must confine ourselves to mentioning the most important of the events that took place behind this military façade.

“ Since the central ruling house was completely powerless, and the feudal lords were virtually independent rulers, little can be said, of course, about any "Chinese" foreign policy. There is less than ever to be said about it for this period of the "Warring States Period". Chinese merchants penetrated southward, and soon settlers moved in increasing numbers into the plains of the south-east. In the north, there were continual struggles with Turkish and Mongol tribes, and about 300 B.C. the name of the Xiongnu (who are often described as "The Huns of the Far East") makes its first appearance. It is known that these northern peoples had mastered the technique of horseback warfare and were far ahead of the Chinese, although the Chinese imitated their methods. The peasants of China, as they penetrated farther and farther north, had to be protected by their rulers against the northern peoples, and since the rulers needed their armed forces for their struggles within China, a beginning was made with the building of frontier walls, to prevent sudden raids of the northern peoples against the peasant settlements. Thus came into existence the early forms of the "Great Wall of China". This provided for the first time a visible frontier between Chinese and non-Chinese. Along this frontier, just as by the walls of towns, great markets were held at which Chinese peasants bartered their produce to non-Chinese nomads. Both partners in this trade became accustomed to it and drew very substantial profits from it. We even know the names of several great horse-dealers who bought horses from the nomads and sold them within China.

Rulers in the Warring States Period

King Wu Of Qin (reigned 310–307) is said have died in powerlifting contest. Mark Oliver wrote in Listverse: King Wu was a massive hulk of a man, obsessed with showing off his muscles. He valued strength above all else. He kicked all the book-reading nerds out of power and filled the highest ranks in his kingdom with musclemen, chosen for their ability to lift heavy things above their heads. That love for lifting heavy things would be his end. One of the strongest men in the kingdom, Meng Yue, challenged him to a cauldron-lifting contest. It seems that Meng won: While Wu was lifting his cauldron up, his knees snapped, and he collapsed. Wu spent about eight months slowly and painfully dying before his body finally gave up, which was bad news for Meng. As his reward for soundly beating the king in a powerlifting contest, Meng and his entire family were hunted down and killed. [Source: Mark Oliver. Listverse, January 12, 2017]

Emperor Wu Of Jin (reigned 266 to 290 B.C.) let a goat choose his concubines.Emperor Wu dedicated most of his time to his harem. He would pull every pretty girl he could find out of her home to make her his concubine, especially preying on his officials’ daughters. This, for Emperor Wu, was important work—so much so that he made it a crime to get married until he was finished picking his concubines. By the end, Emperor Wu had more than 10,000 women in his harem. To choose his partner for the night, he would ride around in a cart drawn by goats. When the goats stopped, he’d sleep with whichever woman they’d brought him to.

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “ “Through the continual struggles more and more feudal lords lost their lands; and not only they, but the families of the nobles dependent on them, who had received so-called sub-fiefs. Some of the landless nobles perished; some offered their services to the remaining feudal lords as soldiers or advisers. Thus in this period we meet with a large number of migratory politicians who became competitors of the wandering scholars. Both these groups recommended to their lord ways and means of gaining victory over the other feudal lords, so as to become sole ruler. In order to carry out their plans the advisers claimed the rank of a Minister or Chancellor. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“Realistic though these advisers and their lords were in their thinking, they did not dare to trample openly on the old tradition. The emperor might in practice be a completely powerless figurehead, but he belonged nevertheless, according to tradition, to a family of divine origin, which had obtained its office not merely by the exercise of force but through a "divine mandate". Accordingly, if one of the feudal lords thought of putting forward a claim to the imperial throne, he felt compelled to demonstrate that his family was just as much of divine origin as the emperor's, and perhaps of remoter origin. In this matter the travelling "scholars" rendered valuable service as manufacturers of genealogical trees. Each of the old noble families already had its family tree, as an indispensable requisite for the sacrifices to ancestors. But in some cases this tree began as a branch of that of the imperial family: this was the case of the feudal lords who were of imperial descent and whose ancestors had been granted fiefs after the conquest of the country.

Others, however, had for their first ancestor a local deity long worshipped in the family's home country, such as the ancient agrarian god Huang Ti, or the bovine god Shen Nung. Here the "scholars" stepped in, turning the local deities into human beings and "emperors". This suddenly gave the noble family concerned an imperial origin. Finally, order was brought into this collection of ancient emperors. They were arranged and connected with each other in "dynasties" or in some other "historical" form. Thus at a stroke Huang Ti, who about 450 B.C. had been a local god in the region of southern Shanxi, became the forefather of almost all the noble families, including that of the imperial house of the Zhou. Needless to say, there would be discrepancies between the family trees constructed by the various scholars for their lords, and later, when this problem had lost its political importance, the commentators laboured for centuries on the elaboration of an impeccable system of "ancient emperors"—and to this day there are sinologists who continue to present these humanized gods as historical personalities.

the six warring states

Warfare During the Warring States Period

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In the earlier wars fought between the nobles they were themselves the actual combatants, accompanied only by their retinue. As the struggles for power grew in severity, each noble hired such mercenaries as he could, for instance the landless nobles just mentioned. Very soon it became the custom to arm peasants and send them to the wars. This substantially increased the armies. The numbers of soldiers who were killed in particular battles may have been greatly exaggerated (in a single battle in 260 B.C., for instance, the number who lost their lives was put at 450,000, a quite impossible figure); but there must have been armies of several thousand men, perhaps as many as 10,000. The population had grown considerably by that time. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The armies of the earlier period consisted mainly of the nobles in their war chariots; each chariot surrounded by the retinue of the nobleman. Now came large troops of commoners as infantry as well, drawn from the peasant population. To these, cavalry were first added in the fifth century B.C., by the northern state of Chao (in the present Shanxi), following the example of its Turkish and Mongol neighbors. The general theory among ethnologists is that the horse was first harnessed to a chariot, and that riding came much later; but it is my opinion that riders were known earlier, but could not be efficiently employed in war because the practice had not begun of fighting in disciplined troops of horsemen, and the art had not been learnt of shooting accurately with the bow from the back of a galloping horse, especially shooting to the rear. In any case, its cavalry gave the feudal state of Chao a military advantage for a short time. Soon the other northern states copied it one after another—especially Qin, in north-west China. The introduction of cavalry brought a change in clothing all over China, for the former long skirt-like garb could not be worn on horseback. Trousers and the riding-cap were introduced from the north.

“The new technique of war made it important for every state to possess as many soldiers as possible, and where it could to reduce the enemy's numbers. One result of this was that wars became much more sanguinary; another was that men in other countries were induced to immigrate and settle as peasants, so that the taxes they paid should provide the means for further recruitment of soldiers. In the state of Qin, especially, the practice soon started of using the whole of the peasantry simultaneously as a rough soldiery. Hence that state was particularly anxious to attract peasants in large numbers.”

Military Advances During the Warring States Period

Dr. Eno wrote: “Perhaps the most basic of these changes concerned the ways in which wars were fought. During the Spring and Autumn years, battles were conducted by small groups of chariot-driven patricians. Managing a two-wheeled vehicle over the often uncharted terrain of a battlefield while wielding bow and arrow or sword to deadly effect required years of training, and the number of men who were qualified to lead armies in this way was very limited. Each chariot was accompanied by a group of infantrymen, by rule seventy-two, but usually far fewer, probably closer to ten. Thus a large army in the field, with over a thousand chariots, might consist in total of ten or twenty thousand soldiers. With the population of the major states numbering several millions at this time, such a force could be raised with relative ease by the lords of such states. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“During the Warring States period, the situation was very different. One reason why the armies of Wu and Yue had been so effective during the period 506-476 B.C. was that they did not employ chariot warfare. The uneven country of the south, split by rivers everywhere, made chariot warfare impractical, and Wu and Yue chose instead to raise massive armies of infantry. Infantry armies moved as rapidly as traditional ones – after all, the infantrymen that accompanied chariots limited the mobility of the whole – and they could be used much more flexibly than armies tied to chariot riding patricians. Horseback command, rather than chariot command, also gave patrician officers more freedom of movement. /+/

“The northern states learned the lessons of the period of Wu-Yue hegemony. The chariot was largely discarded, and instead of concentrating on the size and training of their elite officer corps, patrician lords cultivated huge armies of peasant infantrymen.

Political Impact of Warring States Militarization

Dr. Eno wrote: “The fifth century was an era during which the growth of armies and military technology began to be felt. During the first century of the Warring States era, the new scale of battles made it impossible for the smaller central states to compete. Consequently, the war aims of the larger states began to change. Whereas during the Spring and Autumn period the usual motives of a campaign had been the formation of security alliances, the great states now became outright predators, seeking to occupy and annex the territories of neighboring states. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The results were quickly apparent. Venerable states such as Lu, which fell under the power of Qi, retained only a nominal existence, while one after another, border states between Qin and Wei, Qi and Chu, and Chu and Qin fell prey to the great new armies, whose soldiers now numbered in the hundreds of thousands. /+/

“In consuming their near neighbors, these great states were also eliminating the buffer regions that insulated them against one another. The expansion of their territories increased their shared borders, thus bringing gradually closer the inevitability of a military conflict engaging armies so massive that the casualties of a single campaign could number close to a half million men.” /+/

Rise of the Chinese State During the Warring States Period

Dr. Eno wrote: “During the Warring States years, the overall population of China grew rapidly, spurred by great strides in agricultural technology – the raw material for massive armies was there. Traditional state structures were not conducive to the raising of such numbers of men, however. To achieve the military ends that became increasingly vital to the survival of the state, the patrician lords and their advisors engineered fundamental changes in the structure of the state itself. Three of these changes stand out: 1) the altered relationship between the peasant and the lord; 2) revisions in political administration that increased centralized control to the disadvantage of the patrician class; 3) a sharp rise in social mobility occasioned by the need for true expertise in the management of large armies and growing, centralized states. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Most profoundly changed was the relationship between the lord and the peasantry. The altered military situation now made farmers doubly valuable to their lords: they represented not only his main source of income, but the heart of his war machine as well. Systems of taxation in state after state were reformulated so that the peasant’s payment to his lord no longer took the form of field labor, but was a direct payment in cash or in crops, resources that could sustain the lord’s household or be converted to funds necessary to raise and provision armies. In the course of this transition, the peasantry for the first time were viewed as, in some sense, possessing the lands upon which they paid tax. In some states they were even licensed to buy and sell land, the truest test of ownership in the modern sense. /+/

“The altered relationship between ruler and people is also reflected in the restructuring of administration which occurred in many states. The degree of change varied widely from state to state: among the major states, Chu was probably least touched by them, while Qin was unquestionably the most fundamentally transformed. The nature of the changes also differed among states, but there was a common thread. In virtually all cases, state administration was restructured so that lands and cities were divided into centrally designated units and control over these units was directly determined by the ruler and his close advisors, rather than becoming the hereditary prerogatives of patrician clans. Thus the peasants and city-dwelling commoners fell increasingly under the control of the ruler’s court, and the regional patrician clans more and more found themselves excluded from access to real power. The increased control that the lord exercised aided him in the task of maintaining the state’s readiness in war and coherence in diplomatic policy. /+/

Age of Philosophers

Confucius Confucius Confucianism and Taoism developed in a period of Chinese history from the sixth century to the third century B.C., described as "The Age of Philosophers," which in turn coincided with the Warring States Period.

During the Age of Philosophers, theories about life and god were debated openly at the "Hundred Schools," and vagrant scholars went from town to town, like traveling salesmen, looking for supporters, opening up academies and schools, and using philosophy as a means of furthering their political ambitions. Chinese emperors employed court philosophers who sometimes competed in public debates and philosophy contests, similar to ones conducted by the ancient Greeks.

The uncertainty of this period created a longing for a mythical period of peace and prosperity when it was said that people in China followed rules set by the ancestors and achieved a state of harmony and social stability. The Age of Philosophers ended when the city-states collapsed and China was reunited under Emperor Qin Shihuangdi.

See Separate Article CLASSICAL CHINESE PHILOSOPHY factsanddetails.com See Confucius, Confucianism, Legalism and Taoism Under Religion and Philosophy

Confucius, Mencius, Xunzi and Mozi

Confucius (551-479 B.C.), also called Kong Zi, or Master Kong, looked to the early days of Zhou rule for an ideal social and political order. He believed that the only way such a system could be made to work properly was for each person to act according to prescribed relationships. "Let the ruler be a ruler and the subject a subject," he said, but he added that to rule properly a king must be virtuous. To Confucius, the functions of government and social stratification were facts of life to be sustained by ethical values. His ideal was the junzi (ruler's son), which came to mean gentleman in the sense of a cultivated or superior man. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Mencius (372-289 B.C.), or Meng Zi, was a Confucian disciple who made major contributions to the humanism of Confucian thought. Mencius declared that man was by nature good. He expostulated the idea that a ruler could not govern without the people's tacit consent and that the penalty for unpopular, despotic rule was the loss of the "mandate of heaven." [Ibid]

Mencius (372-289 B.C.), or Meng Zi, was a Confucian disciple who made major contributions to the humanism of Confucian thought. Mencius declared that man was by nature good. He expostulated the idea that a ruler could not govern without the people's tacit consent and that the penalty for unpopular, despotic rule was the loss of the "mandate of heaven." [Ibid]

The effect of the combined work of Confucius, the codifier and interpreter of a system of relationships based on ethical behavior, and Mencius, the synthesizer and developer of applied Confucian thought, was to provide traditional Chinese society with a comprehensive framework on which to order virtually every aspect of life. There were to be accretions to the corpus of Confucian thought, both immediately and over the millennia, and from within and outside the Confucian school. Interpretations made to suit or influence contemporary society made Confucianism dynamic while preserving a fundamental system of model behavior based on ancient texts. [Ibid]

Diametrically opposed to Mencius, for example, was the interpretation of Xun Zi (ca. 300-237 B.C.), another Confucian follower. Xun Zi preached that man is innately selfish and evil and that goodness is attainable only through education and conduct befitting one's status. He also argued that the best government is one based on authoritarian control, not ethical or moral persuasion. Xun Zi's unsentimental and authoritarian inclinations were developed into the doctrine embodied in the School of Law (fa), or Legalism. The doctrine was formulated by Han Fei Zi (d. 233 B.C.) and Li Si (d. 208 B.C.), who maintained that human nature was incorrigibly selfish and therefore the only way to preserve the social order was to impose discipline from above and to enforce laws strictly. The Legalists exalted the state and sought its prosperity and martial prowess above the welfare of the common people. Legalism became the philosophic basis for the imperial form of government. When the most practical and useful aspects of Confucianism and Legalism were synthesized in the Han period (206 B.C.-A.D. 220), a system of governance came into existence that was to survive largely intact until the late nineteenth century. *

Still another school of thought was based on the doctrine of Mo Zi (470-391 B.C.”), or Mo Di. Mo Zi believed that "all men are equal before God" and that mankind should follow heaven by practicing universal love. Advocating that all action must be utilitarian, Mo Zi condemned the Confucian emphasis on ritual and music. He regarded warfare as wasteful and advocated pacificism. Mo Zi also believed that unity of thought and action were necessary to achieve social goals. He maintained that the people should obey their leaders and that the leaders should follow the will of heaven. Although Moism failed to establish itself as a major school of thought, its views are said to be "strongly echoed" in Legalist thought. In general, the teachings of Mo Zi left an indelible impression on the Chinese mind. [Source: The Library of Congress]

Confucius and the Shi Class

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Review of Books: “Back in the Warring States Period, rising literacy and urbanization gave rise to a class of gentlemen scholars, or shi, who advised kings; some thought that they might be better qualified than the person born to the throne—the origins of the meritocracy argument. Today, similar trends are at work, but on a much broader scale. Now, instead of a scholar class that wants a say, it is the entire population. One might even say that” ancient “texts show a more freewheeling society than today’s. Here we encounter a past that was home to vigorous debates—a place where Confucians approved of kings abdicating, and might even have fancied themselves capable of ruling. Today’s China also has such ideas, but like the bamboo slips before their discovery, they are buried and their excavation taboo. [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Review of Books, April 21, 2016]

Mencius Dr. Eno wrote: “ The division of Jin in 453 B.C., in which a ruling house sanctioned by Zhou tradition was displaced by three upstart patrician clans who sliced the old state into smaller ones over which they ruled, was part of a larger process in which the prerogatives of the old patrician class began to decay. While it is possible to view this as the end of the Zhou aristocracy, it is probably more accurate to say instead that the boundary between the older clans of high birth and the common people became more porous. It is during this period that the word “shi,” denoting a trained warrior possessing the learning and etiquette of the nobility, came to be applied to a class of people, and the characteristics of the members of the shi class came to be viewed as a function of training rather than birth (though of course, birth still largely determined who was likely to receive training). Being a shi thus became a goal rather than a mere fact. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The most famous theoretician of this new view of the manly ideal was Confucius (551-479 B.C.), and although he died before the beginning of the Warring States period, his life and ideas also serve as an appropriate starting point for a Warring States narrative. To review briefly some of the most relevant aspects of Confucius’s career and influence, Confucius was born of parents who were probably members of patrician lineages of very low standing. “When young,” he once remarked, “I was of low station, hence I had to become skilled in many humble arts.” Confucius lived in a patrician state that was undergoing progressive political disintegration. The dukes of Lu had, like those of the much greater state of Jin, lost much of their power to a group of warlord clans. In Lu, these clans were all cadet branches of the ruling Ji lineage (the royal lineage of the house of Zhou, descended, in the case of Lu, from the Duke of Zhou). The warlord clan leaders controlled most of the territory of Lu and their influence at the ducal court was paramount. Their own clan lands were generally controlled by powerful stewards, able retainers in the paid service of these warlords. /+/

“The distinctive character of the state of Lu had, in the past, been derived from its association with the Duke of Zhou, whose contributions to the establishment of the Zhou state in the eleventh century had been so great. As his descendants, the dukes of Lu were entitled to employ ritual, music, and sacrificial forms otherwise reserved for the Son of Heaven alone. Lu was seen as preserving the ritual forms and learning of the early Western Zhou, and it possessed a special type of cultural legitimacy. The warlord clans, however, by destroying both the political and the ritual order of the state were destroying this state character.Confucius, for reasons that seem personal and lost to history, developed a deep affinity for the decaying rituals of the Zhou, and in his mind, he seems to have associated those forms of ceremony and etiquette with the prodigious political success of the Zhou founders. For Confucius, the warlord society of the Spring and Autumn period showed a sharp decline in both the moral values of society and the forms of social, religious, and court behavior. He saw these dimensions as intertwined, and became deeply committed to restoring ethical and political order through restoration of ritual order and personal morality. /+/

“However, Confucius’s situation was paradoxical. He was an advocate of the old patrician order, but being of low birth, he himself could play no legitimate role in the revival he sought. From this background, Confucius developed a very powerful combination program. He preached a conservative restoration of the patrician society of the Zhou, but he maintained as a radical tenet that personal virtue, rather than birth, was the qualification for membership in the ruling elite. For him, virtue was expressed in terms of ritual skills and humane dedication to social rather than personal advantage. At the same time, Confucius looked to the existing “legitimate” sovereigns, men like the Zhou kings or the dukes of Lu, as the best potential bases for a social revolution. All things being equal, birth still counted. If the men who occupied the thrones of the Zhou patrician rulers could, by means of revived personal virtue (and the aid of morally talented men like Confucius), lead the population as a whole, the new order could be more effectively established.” /+/

Impact of Confucius

Dr. Eno wrote: “During his younger life, Confucius attracted a number of political actors in the state of Lu, who came to him to learn more about Zhou ritual forms and his own political views (which he came to claim reflected those of the sages of the past, including the Zhou founders). Two of these men were actually stewards of the leading warlord clans – men of substantial influence. It appears that Confucius plotted with them to arrange an effective disarmament of the warlord strongholds and a restoration of legitimate ducal power. Presumably, Confucius hoped that his assistance to a revived ducal house would induce the dukes to change their policies and behavior along Confucian lines as well. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“About 500 B.C., Confucius and his disciples put their plan into action. It did not work. The outcome was that Confucius fled into exile and, for the next fifteen years, he wandered with many of his disciples from state to state in eastern China, looking for a ruler who would adopt his policies and employ him as minister. The search was fruitless, and about 485 B.C., one of his disciple-stewards in Lu, having made major contributions to his master in war, brokered an arrangement whereby Confucius was allowed to return to Lu and live in retirement as a teacher. Confucius died in Lu in 479 B.C.

“While Confucius saw himself as a revivalist, the impact of his teachings was entirely radical. It is doubtful whether the intensely ritualized past on which he modeled his ideal future had ever existed in the form he imagined. In fact, Confucius’s dual celebration of legitimate rulers and men of moral talent left little role for the hereditary patrician class. Few class members belonged to ruling lineages, and if social and political prestige was to be tied to issues of etiquette and learning rather than birth, what significant advantage did this leave them? Confucius was known to accept as a disciple any man who could afford as little as a (proverbial) bundle of sausages for tuition. While it may be doubtful how many of Confucius’s own disciples rose to high rank, his ideas spurred a new growth industry of private teachers who trained all comers for participation in the political and military arenas. /+/

“Confucians also seem to have made a radical reconfiguration of the past in their story of the history of Chinese culture. In the Confucian account of China’s history, the founding rulers and most perfect sages are the three emperors Yao, Shun, and Yu (known as the founder of the Xia Dynasty). The first two are particularly revered. The mythology connected with Yao and Shun places great emphasis on the fact that they chose not to pass along their thrones to their sons. Instead, acting in a way radically different from the norms of the truly historical periods of the Shang and Zhou, they passed the throne on the basis of merit alone, without any consideration of birth. According to the Confucian story, Shun and Yu were chosen solely as the most worthy men of the land; their fathers are, in fact, generally pictured as evil men of uncertain social background. This mythology seems to reflect an important tendency among Warring States Confucians to attack the very notion of hereditary legitimacy, for rulers as well as for patrician warlords. In this way, Confucius represents the articulation of an ideology that challenges the exclusivity of the patrician class, and reconceives the very notion of the patrician as a person of high worth, rather than a person of high birth.” /+/

Shang Yang

Shang Yang

One of the most important figures of the Warring States periods is Shang Yang, a 4th century B.C. administrator who established a set of laws designed "to punish the wicked and rebellious, in order to preserve the rights of the people."

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Lord Shang (d. 338 B.C., also known as Gongsun Yang or Shang Yang) was prime minister of the state of Qin in the middle of the fourth century B.C. — when Qin was simply one of the many states of the weak and fragmented feudal kingdom of Zhou. Lord Shang was from the neighboring state of Wei. Hearing that Duke Xiao of Qin was seeking men of worth to help strengthen his state, he left Wei in 361 B.C. to find his fortune in Qin. As an advisor to Duke Xiao, Lord Shang recommended revising the laws. When some of the Duke’s other advisors expressed reservations, Lord Shang is said to have responded: “Wise men make laws; stupid men are constrained by them.” [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Dr. Eno wrote: “ If we rely on the historical texts that have been left to us to determine the greatest turning point of Classical Chinese political history, it would be the ministry of Shang Yang in the state of Qin. While it is undoubtedly true that the histories exaggerate his achievements, it is still likely that the reality was extraordinary. Shang Yang was a political thinker who reflected his times, and it may be that even without his personal efforts, the same general outcome of the chaotic years of the Warring States era would have been brought about in time – another Shang Yang would have eventually arisen. But Shang Yang’s career is no less remarkable for that. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

Mao Zedong's earliest surviving essay, written when he was 19, praised the pragmatic but ruthless policies of Shang Yang. Mao concluded, "At the beginning of anything out of the ordinary, the mass of the people always dislike it." Yang's policy's paved the way for the brutal but unifying rule of Emperor Qin.

See Separate Article SHANG YANG AND LI SHI: THE IMPLEMENTORS OF LEGALISM factsanddetails.com

Changes to Agriculture and Feudalism in the Warring States Period

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In the course of the wars much land of former noblemen had become free. Often the former serfs had then silently become landowners. Others had started to cultivate empty land in the area inhabited by the indigenous population and regarded this land, which they themselves had made fertile, as their private family property. There was, in spite of the growth of the population, still much cultivable land available. Victorious feudal lords induced farmers to come to their territory and to cultivate the wasteland. This is a period of great migrations, internal and external. It seems that from this period on not only merchants but also farmers began to migrate southward into the area of the present provinces of Kwangtung and Kwangsi and as far as Tonking. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“As long as the idea that all land belonged to the great clans of the Zhou prevailed, sale of land was inconceivable; but when individual family heads acquired land or cultivated new land, they regarded it as their natural right to dispose of the land as they wished. From now on until the end of the medieval period, the family head as representative of the family could sell or buy land. However, the land belonged to the family and not to him as a person. This development was favoured by the spread of money. In time land in general became an asset with a market value and could be bought and sold.

“Another important change can be seen from this time on. Under the feudal system of the Zhou strict primogeniture among the nobility existed: the fief went to the oldest son by the main wife. The younger sons were given independent pieces of land with its inhabitants as new, secondary fiefs. With the increase in population there was no more such land that could be set up as a new fief. From now on, primogeniture was retained in the field of ritual and religion down to the present time: only the oldest son of the main wife represents the family in the ancestor worship ceremonies; only the oldest son of the emperor could become his successor. But the landed property from now on was equally divided among all sons. Occasionally the oldest son was given some extra land to enable him to pay the expenses for the family ancestral worship. Mobile property, on the other side, was not so strictly regulated and often the oldest son was given preferential treatment in the inheritance.

“The technique of cultivation underwent some significant changes. The animal-drawn plough seems to have been invented during this period, and from now on, some metal agricultural implements like iron sickles and iron plough-shares became more common. A fallow system was introduced so that cultivation became more intensive. Manuring of fields was already known in Shang time. It seems that the consumption of meat decreased from this period on: less mutton and beef were eaten. Pig and dog became the main sources of meat, and higher consumption of beans made up for the loss of proteins. All this indicates a strong population increase. We have no statistics for this period, but by 400 B.C. it is conceivable that the population under the control of the various individual states comprised something around twenty-five millions. The eastern plains emerge more and more as centres of production.

Economic and Social Changes During the Warring States Period

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “The increased use of metal and the invention of coins greatly stimulated trade. Iron which now became quite common, was produced mainly in Shanxi, other metals in South China. But what were the traders to do with their profits? Even later in China, and almost down to recent times, it was never possible to hoard large quantities of money. Normally the money was of copper, and a considerable capital in the form of copper coin took up a good deal of room and was not easy to conceal. If anyone had much money, everyone in his village knew it. No one dared to hoard to any extent for fear of attracting bandits and creating lasting insecurity. On the other hand the merchants wanted to attain the standard of living which the nobles, the landowners, used to have. Thus they began to invest their money in land. This was all the easier for them since it often happened that one of the lesser nobles or a peasant fell deeply into debt to a merchant and found himself compelled to give up his land in payment of the debt. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“Soon the merchants took over another function. So long as there had been many small feudal states, and the feudal lords had created lesser lords with small fiefs, it had been a simple matter for the taxes to be collected, in the form of grain, from the peasants through the agents of the lesser lords. Now that there were only a few great states in existence, the old system was no longer effectual. This gave the merchants their opportunity. The rulers of the various states entrusted the merchants with the collection of taxes, and this had great advantages for the ruler: he could obtain part of the taxes at once, as the merchant usually had grain in stock, or was himself a landowner and could make advances at any time. Through having to pay the taxes to the merchant, the village population became dependent on him. Thus the merchants developed into the first administrative officials in the provinces.

“In connection with the growth of business, the cities kept on growing. It is estimated that at the beginning of the third century, the city of Lin-chin, near the present Chi-nan in Shandong, had a population of 210,000 persons. Each of its walls had a length of 4,000 metres; thus, it was even somewhat larger than the famous city of Loyang, capital of China during the Later Han dynasty, in the second century A.D. Several other cities of this period have been recently excavated and must have had populations far above 10,000 persons. There were two types of cities: the rectangular, planned city of the Zhou conquerors, a seat of administration; and the irregularly shaped city which grew out of a market place and became only later an administrative centre. We do not know much about the organization and administration of these cities, but they seem to have had considerable independence because some of them issued their own city coins.

“When these cities grew, the food produced in the neighborhood of the towns no longer sufficed for their inhabitants. This led to the building of roads, which also facilitated the transport of supplies for great armies. These roads mainly radiated from the centre of consumption into the surrounding country, and they were less in use for communication between one administrative centre and another. For long journeys the rivers were of more importance, since transport by wagon was always expensive owing to the shortage of draught animals. Thus we see in this period the first important construction of canals and a development of communications. With the canal construction was connected the construction of irrigation and drainage systems, which further promoted agricultural production. The cities were places in which often great luxury developed; music, dance, and other refinements were cultivated; but the cities also seem to have harboured considerable industries. Expensive and technically superior silks were woven; painters decorated the walls of temples and palaces; blacksmiths and bronze-smiths produced beautiful vessels and implements. It seems certain that the art of casting iron and the beginnings of the production of steel were already known at this time. The life of the commoners in these cities was regulated by laws; the first codes are mentioned in 536 B.C. By the end of the fourth century B.C. a large body of criminal law existed, supposedly collected by Li K'uei, which became the foundation of all later Chinese law. It seems that in this period the states of China moved quickly towards a money economy, and an observer to whom the later Chinese history was not known could have predicted the eventual development of a capitalistic society out of the apparent tendencies.

Horizontal and Vertical Alliances in Warring States China (320-256 B.C.)

Dr. Eno wrote: “The last century of the Classical age is among the most dynamic in Chinese history. Long brewing trends of change in government structures, intellectual imagination, and many aspects of economic and material culture all seem to rise to the surface. Because traditional historians viewed the periodization of Chinese history in terms of dynastic eras, they often failed to see just how far the final century of the Zhou order had departed from the norms of the Classical age. The new Imperial state that was founded by the Qin Dynasty in 221 B.C. is in many ways a culmination of Warring States trends, rather than a sudden new social order imposed on China through conquest. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“By the closing years of the fourth century, virtually all the geographical buffers that softened the power struggle among the major powers had disappeared. Qin, Chu, and Qi dwarfed all other states in terms of territory, influence, and military strength. The rulers of all three had taken the title of King, and it was becoming clear that a final struggle to succeed to the throne of the Zhou rulers had begun. Unlike the Zhou founders, who were said to have conquered the Shang in a single morning, this time the battles for the Mandate were destined to stretch on for many years at the cost of blood beyond measure. /+/

“The initial stage of this period is known for a particular type of political contest in which the three powers engaged. As it became apparent that the future would belong to Qin unless the other states could bring their military forces into powerful combinations, some of the rulers and ministers among these states began to engage in the most ambitious alliance building since the age of the hegemons. These alliances, which sought to block the eastward advance of Qin troops by building the barrier of a North-South coalition of states, were known as “Vertical Alliances.” For centuries, one of the cornerstones of Qin’s political strength was the military advantage it enjoyed by virtue of its geographical position. Not only was it located in the far west, which insulated it from attack by states in the east or southeast, its terrain was a mountain basin, easily guarded at the few strategic mountain passes that would allow military movement in and out of the state. Through these passes, which Qin controlled, Qin armies could issue forth towards the east and south, but an army of invasion would need enormous strength to breach these well defended gateways to Qin. /+/

“Now, however, with Qin’s ambitions focused on expansion, its geographical position became a disadvantage. Qin was distant from China’s center of gravity. Its goal to stretch eastward was clearly vulnerable to the counter-strategy envisioned by a north-south defensive coalition: a Vertical Alliance. /+/

“But Qin had many cards to play in dealing with those who might join a Vertical Alliance. As the strongest military force in China, it could coerce its near neighbors into obeying its will against their own long-term interests, and it could trade some of its vast territories for the short-term allegiance of rulers who could not see into the future. In this way, traveling ministers from Qin were able frequently to bully or persuade the governments of other states to join it in an east-west “Horizontal Alliance,” which could parry threats against Qin and provide Qin armies with routes of access towards the east.” /+/

Fall of Qi

The state of Yan was long occupied by the Qi troops and the Yan didn’t like it. . Dr. Eno wrote: “Eventually, confident that Yan was secure, King Xuan of Qi withdrew his armies from Yan. The king of Yan immediately issued a call for wise men to come to his capital, and among those he treated with the greatest courtesies were men known for their abilities in military administration. King Zhao worked tirelessly to build the armies of Yan into a force capable of exacting revenge on Qi, while at the same time, Qi conducted itself with great arrogance in relations with other states, creating a broad coalition of enemies who were most anxious to aid Yan should it move against Qi. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“It took many years, but in 284 B.C., long after the death of King Xuan of Qi, King Zhao sent the armies of Yan along with allies from almost all the major states south to invade Qi. He was rewarded for his patient devotion to his cause. The troops of Qi were routed and the new king of Qi, King Min, fled south into the small outpost garrison of Ju, where he was soon assassinated. Meanwhile, Yan sacked Linzi, the capital of Qi, burning the palaces and temple shrines and shipping the treasures of the city north to Yan. /+/

“Qi was divided into military districts and administered by Yan until 279 B.C. In that year at last, the Qi heir returned to the capital behind a vanguard of troops which had been maintained in exile, and in the space of a few days, the armies of Yan were driven out and the entire kingdom of Qi restored. But Qi’s power was permanently broken. From that time on, its diplomatic policies were entirely devoted to appeasement. It was no longer a great power, and the vacuum of power in the east that was thus created played a major role in allowing Qin to achieve its ultimate victor.

End of the Warring States Period and Beginning of the Qin Dynasty

Dr. Eno wrote: “The final years of the Warring States period are a whirlwind of bloody battles and sieges, alliances and betrayals. First Chu, benefiting from the crippling of Qi, began to expand, controlling almost all of southern China. But Qin responded with a swift campaign, seized the capital of Ying for good, and threw the center of gravity of the Chu state eastwards, where it was less able to join with other states. Then, with no one strong opponent, the generals and ministers of Qin coordinated a policy of encouraging its enemies to fight one another, with Qin collecting the spoils after the combatants were too weary to protest. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“Qin’s conquest was gradual, but relentless. Once the brilliant and ruthless Li Si was firmly established as minister under King Zheng, who was now soon to become the First Emperor, the pace quickened. In 230 B.C., the major states began to fall: first Han, then Zhao (228 B.C.), Yan (226 B.C.), Wei (225 B.C.), Chu (223 B.C.), and finally the once mighty state of Qi. /+/

“The period of political fragmentation and civil war was over at last. The grip of the new government over its conquered territories seemed absolute, and its willingness to employ the most extreme forms of political terror against its own populace appeared to allow no room for rebellion. Who could have guessed that wars even more destructive than those of the past century would erupt again only twelve years later and that these would within three more years sweep the Qin Empire entirely away? /+/

Despite the fact that the rule of Qin lasted only a short season in China, and the fact that the fear with which Qin was regarded by the other states of Classical China was matched by the disdain that later historians would express for the brief period of Qin’s autocratic control of all China, the Qin conquest was, in essence, a revolutionary movement, that brought an end not only to political disarray, but to social, political, economic, and intellectual systems that were characteristic of the Classical era. The Qin government was able to effect such dramatic transformations only because throughout the Warring States period, the competing states and cultures of late Zhou China were, without much awareness of the fact, actually undergoing deep social transitions. In this sense, the revolutionary dimensions of the Qin conquest should be seen more as a culmination of a long process, rather than the sudden initiation of change. As we explore the society of Warring States China through further readings, we will observe the accelerating changes that led to the birth of the Imperial state under the Qin and its survival after the Qin collapse. /+/

See Separate Article QIN DYNASTY (221-206 B.C.) AND THE RISE AND FALL OF THE QIN STATE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, University of Washington

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021