IMPERIAL CHINESE BUREAUCRACY

The Chinese established the world’s first meritocracy — a bureaucracy based on skill and education rather than birth, property and bloodlines. This system was considered key to Imperial China's success and longevity. Emperors and kingdoms came and went but Chinese civilization remained in place as a result of the well-organized administrative system run by scholars-bureaucrats.

The Chinese established the world’s first meritocracy — a bureaucracy based on skill and education rather than birth, property and bloodlines. This system was considered key to Imperial China's success and longevity. Emperors and kingdoms came and went but Chinese civilization remained in place as a result of the well-organized administrative system run by scholars-bureaucrats.

The Chinese civil service has roots that go back at least 2,500 years but became formalized in its modern form during the Qing Dynasty (1644-1912). Largely based on principals set down by Confucius in the 6th century B.C., it provided the the only way to a better life and families did everything they could to get their sons in. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “During the time that the Qing dynasty ruled China, the ideas of a civil government based on meritocracy and social responsibility were admired and promoted by prominent writers and philosophers of the 18th-century Enlightenment period in Europe and the 19th-century Transcendentalist movement in America, including Voltaire in France, English diplomats serving in China, and Ralph Waldo Emerson in the United States. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Madeleine Zelin, Consultant, learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu ]

The Emperor needed the Confucian bureaucrats to administer his realm and the Confucian bureaucrats needed the Emperor for employment and legitimacy but there was always tensions in their relationship. The bureaucrats feared the despotic tendencies of the Emperor and the Emperor feared the bureaucrats would turn on him and favor the people rather than him.

Many Confucian bureaucrats operated as local leaders. They served as links between the masses and the Emperor and often functioned as landlords and tax collectors. When times were good the system worked well but when times were bad---as a result of corruption, natural disasters or war---the relations between the bureaucrats, the people and the Emperor became strained. Sometimes the system collapsed and a period of disorder and chaos persisted until strong leadership emerged and the system could be restored.

Under this system China changed very little. The government was unresponsive and unrepresentative of the people and was concerned with control and order. It had little contact with the people it ruled. Many would say the same situation exists today.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; CHINESE DYNASTIES AND RULERS factsanddetails.com; CHINESE EMPEROR AND IMPERIAL RULE IN ANCIENT CHINA factsanddetails.com; EUNUCHS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; CHINESE LITERATI AND SCHOLAR-ARTIST-POETS factsanddetails.com; CHINESE IMPERIAL EXAMS factsanddetails.com; VILLAGE EDUCATION AND SCHOLARS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; EXAMS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; VILLAGE SCHOOLS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Imperial China (DK Classic History)” Amazon.com; “Imperial China, 900–1800" by F. W. Mote Amazon.com; “Chronicle of the Chinese Emperors: The Reign-by-Reign Record of the Rulers of Imperial China” by Ann Paludan Amazon.com; “Chinese emperors from the Xia Dynasty to the Fall of the Qing Dynasty” by Ma Yan by Ma Yan and Beautifully Illustrated Amazon.com; “The Eunuchs in the Ming Dynasty” by Shih-Shan Henry Tsai ( Amazon.com; “The Forbidden City” by Geremie Barme Amazon.com

Temples of the State Cult in China

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “In addition to supporting Confucianism through the civil service examination system, the state was deeply involved in other areas of life that had a major impact on religious practice and belief. Some have referred to this as the State Cult. The arrangement of state ritual below the emperor was coordinated exactly with the national administrative system. At each administrative level -- province, prefecture, and county -- there was a city or town serving as the administrative seat, where in addition to the government compound (yamen) which was the officiating magistrate’s headquarters, there were several official religious establishments: Among the most important were the Confucian or civil temple (wen miao), and the military temple (wu miao), which were the ritual foci of the two major divisions in the Chinese bureaucracy; and also the City God temple (chenghuang miao). A city serving as both prefectural seat and county seat would have two yamen and two sets of state temples. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia]

“Confucian Temples: The Confucian temple housed a spirit tablet dedicated to Confucius himself, along with a collection of spirit tablets dedicated to various important scholars in the Confucian canon (many of these being Confucius’ own disciples; others would be eminent Confucian scholars from later times). Rites at the Confucian temple were held by and for government officials of the district, as well as for the vastly larger number of degree-holders not in office. All the degree-holders of a district were required to attend the annual worship at the temple of Confucius on his birthday.

Military Temples: The military temple was the major temple for local people who had obtained degrees in the military examination system and were part of the military bureaucracy, which was subordinate to the civil bureaucracy. The military temple was devoted to the god of war, Guan Yu, and housed spirit tablets dedicated to Guan Yu as well as other figures who represented loyalty and patriotism, the two key values promoted in the military temples.

Scholar-Officials (Mandarins) in China

Ming-era scholar

The scholar-bureaucrats who ran the Chinese imperial government were known in the West as Mandarins (a term coined by the British, which is viewed as pejorative and out of date). They were China's best and brightest, and served the Emperor in the imperial court and as imperial magistrates and representatives in the hinterlands.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: ““Those who had the ambition to become government officials were schooled from an early age in the canonical literature and the philosophical works of China's great Confucian tradition. It was through this learning that would-be officials would not only be able to formulate a personal, moral and ethical structure for themselves, their family, and their local community, but also develop an understanding of how one should appropriately act as a member of the group of people that rules the state. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Madeleine Zelin, Consultant, learn.columbia.edu/nanxuntu]

“Examinations were given at the county level, and successful candidates progressed to higher levels, all the way to the highest-level examinations, which were given at the imperial capital. If one could pass the examinations at this level, then chances were very great that one would certainly become a member of the small coterie of elite bureaucrats that ruled China. Of course, the ability of someone to get the education needed to sit for these examinations relied to a certain extent on wealth, although families often coordinated their wealth so that the brightest and most promising of their children would be able to rise through this system.”

In the 19th century a Chin-shih (“Entered Scholar”) held a third literary degree, the rough equivalent of a Doctor in Literature. Chü-Jên (“Selected man”) held a second full literary degree, the rough equivalent of a Masters degree. Hsiu-ts‘ai (“Flourishing Talent”) was the lowest of the several literary degrees, roughly equivalent to a Bachelor of Arts. The Han-lin (“Forest of Pencils”) was the last literary degree. It entitling one to hold office. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur Henderson Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

Lifestyle of Chinese Scholar-Officials

Scholar-officials worked hard: 10-day work weeks and work days that often started at 5:00am. They oversaw the regulation of trade, managed the money supply, maintained security in the provinces, and settled legal disputes. Scholar-officials were well rewarded for their work. They enjoyed lavished banquets several times a week and often lived in luxurious homes with their own concubines and entertainers.

Ming-era scholar

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Outside of a one-day break for every 10 workdays and the New Year's holiday, Qing officials were generally not given holidays. For personal engagements such as visiting the relatives, the officials must ask for personal leave. However, for officials who were sent on an occasional work-related trip (such as the imperial commissioner), they were often granted permission to ask for personal leaves to visit their parents or fulfill the tomb-sweeping rituals prior to returning to the capital. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei ]

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “The leisure activities of the literati class are well-represented in paintings of the Song and Yuan periods; one of the most common of these being the gathering of officials and others of literary talent in a garden setting for the pleasures of reading, composing poetry, and appreciating works of art and antiquities. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv]

During the Qing dynasty, members of the court and the bureaucracy displayed their rank with decorative patterns and precious metals and gems worn on their costumes. The formal over-robe worn at court by a first degree civil servant, for example, was embroidered with a crane while that of a second degree civil servant was embroidered with a golden pheasant. The clothes of lower ranked officials were decorated with embroideries of other animals.

Status for high officials was also indicated by the number of porters that carried their sedan chairs. During the Qing Dynasty officials of the top seven levels used sedan chair carried by four porters. Princes were transported in ones carried by eight. The Emperor and his mother were allowed 24. Generals and other military leaders were not granted this privilege.

History of the Scholar–Officials in China

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “Beginning about the fourth century B.C., ancient texts describe Chinese society as divided into four classes: the scholar elite, the landowners and farmers, the craftsmen and artisans, and the merchants and tradesmen. Under imperial rule, the scholar elite, whose exemplar was Confucius, directed the moral education of the people; the farmers produced food; the craftsmen made things that were useful; and the merchants promoted luxury goods. Because in theory the Confucian elite advocated simple rural values as opposed to a taste for luxury (which they viewed as superfluous, leading to moral degeneration), the merchants who sold for profit, adding nothing of value to society, ranked low on the social scale (though, in reality, economic success had its obvious advantages). [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“The unique position occupied by the scholar elite in Chinese society has led historians to view social and political change in China in light of the evolving status of the scholar. One theory holds that the virtues of the scholars were appreciated only in times of cultural upheaval, when their role was one of defending, however unsuccessfully, moral values rather than that of performing great tasks. Another theory, relating to art and political expression in Han-dynasty China, offers an analysis of the tastes and habits of the different social classes: "the imperial bureaucracy, not the marketplace, was [the scholar's] main avenue to success, and he was of use to that bureaucracy only insofar as he placed the public good above his own. … [Thus] the art of the Confucian scholar was … inherently duplicitous and was encouraged to be so by the paradoxical demands [that Chinese] society made upon its middlemen." \^/

Ming-era scholar

“Beginning in the late tenth century, in the early Northern Song, the government bureaucracy was staffed entirely by scholar-officials chosen through a civil examination system. The highest degree, the jinshi ("presented scholar"), was awarded as the culmination of a three-stage process. The examinations produced 200 to 300 jinshi candidates each year. By the late eighteenth century, China's population had grown to about 300 million. The more than 1,200 counties, divided into eighteen provinces, were governed through an imperial bureaucracy of only 3,000 to 4,000 ranked degree-holding officials. The officials ruled the land with the help of local gentry and locally recruited government clerks. Because the governmental superstructure was so thinly spread, it was heavily invested in the Confucian virtue ethic as the binding social force—and when that failed, in the use of harsh punishment—for maintaining stability and order. \^/

“This system operated as a mechanism through which the state replaced entrenched local hereditary landowners and rich merchants with people whose authority was conferred (and could easily be removed) by the state. Scholar-officials, unlike the other three social classes, did not therefore constitute an economic class as such, as their only power resided in their Confucian ideals and their moral and ethical values. Nevertheless, the landowners, the craftsmen, and the merchants were controlled by the state and the state was administered by the scholar-officials, who discouraged entrepreneurial endeavor and the accumulation of wealth with the Confucian admonition that acceptance of limitations leads to happiness. \^/

“Government administration and culture were from the outset the two primary concerns of the scholar. Beginning in the late Northern Song, with the growth of literacy but with a fixed quota for civil examination candidates (and therefore limited opportunities for official employment), scholars increasingly turned to the arts, the study of which was considered a path to the cultivation of the moral self. Responding to both perceived and real moral deterioration, governmental corruption, and societal ills and subscribing to the belief that a return to the past, a turning back to the teachings of the ancients, would transform human society, the scholar-artists pursued the study of early calligraphy and painting. Private collections of ancient works were amassed, and scholarship in such fields as archaeology and epigraphy flourished. Scholar-officials also became particularly associated with the Four Accomplishments: painting, poetry, a chesslike game of strategy known as weiqi (go in Japanese), and playing the zither (qin). In the area of paintings, scholar-artists beginning in the Yuan dynasty developed and were closely associated with a highly expressive style of painting that utilized nonrepresentational calligraphic brushwork to create pictures, most typically landscapes, that revealed the inner spirit of the painter rather than a realistic depiction of the subject." \^/

Confucianism and Government in the Chinese Imperial Era

Confucianism originated and developed as the ideology of professional administrators and continued to bear the impress of its origins. Imperial-era Confucianists concentrated on this world and had an agnostic attitude toward the supernatural. They approved of ritual and ceremony, but primarily for their supposed educational and psychological effects on those participating. Confucianists tended to regard religious specialists (who historically were often rivals for authority or imperial favor) as either misguided or intent on squeezing money from the credulous masses. The major metaphysical element in Confucian thought was the belief in an impersonal ultimate natural order that included the social order. Confucianists asserted that they understood the inherent pattern for social and political organization and therefore had the authority to run society and the state. [Source: Library of Congress *]

Confucius The Confucianists claimed authority based on their knowledge, which came from direct mastery of a set of books. These books, the Confucian Classics, were thought to contain the distilled wisdom of the past and to apply to all human beings everywhere at all times. The mastery of the Classics was the highest form of education and the best possible qualification for holding public office. The way to achieve the ideal society was to teach the entire people as much of the content of the Classics as possible. It was assumed that everyone was educable and that everyone needed educating. The social order may have been natural, but it was not assumed to be instinctive. Confucianism put great stress on learning, study, and all aspects of socialization. Confucianists preferred internalized moral guidance to the external force of law, which they regarded as a punitive force applied to those unable to learn morality. *

Confucianists saw the ideal society as a hierarchy, in which everyone knew his or her proper place and duties. The existence of a ruler and of a state were taken for granted, but Confucianists held that rulers had to demonstrate their fitness to rule by their "merit." The essential point was that heredity was an insufficient qualification for legitimate authority. As practical administrators, Confucianists came to terms with hereditary kings and emperors but insisted on their right to educate rulers in the principles of Confucian thought. Traditional Chinese thought thus combined an ideally rigid and hierarchical social order with an appreciation for education, individual achievement, and mobility within the rigid structure. *

While ideally everyone would benefit from direct study of the Classics, this was not a realistic goal in a society composed largely of illiterate peasants. But Confucianists had a keen appreciation for the influence of social models and for the socializing and teaching functions of public rituals and ceremonies. The common people were thought to be influenced by the examples of their rulers and officials, as well as by public events. Vehicles of cultural transmission, such as folk songs, popular drama, and literature and the arts, were the objects of government and scholarly attention. Many scholars, even if they did not hold public office, put a great deal of effort into popularizing Confucian values by lecturing on morality, publicly praising local examples of proper conduct, and "reforming" local customs, such as bawdy harvest festivals. In this manner, over hundreds of years, the values of Confucianism were diffused across China and into scattered peasant villages and rural culture. *

Song Dynasty Bureaucracy

Some argue the scholar-officials reached their peak under the Song Dynasty (960-1279). The founders of the Song dynasty built an effective centralized bureaucracy staffed with civilian scholar-officials. Regional military governors and their supporters were replaced by centrally appointed officials. This system of civilian rule led to a greater concentration of power in the emperor and his palace bureaucracy than had been achieved in the previous dynasties. The northern Song dynasty emphasized "orderly and virtuous governance, achieved largely through efficient bureaucracy staffed by mandarins who passed the rigorous state examinations...the revival of Confucian teaching gave a particularly strong moral flavor to the dynasty."

Song rule featured a bureaucratic ruling class that derived its legitimacy from philosophical orthodoxy and an economy that involved an increasingly active free peasantry interacting with large urban commercial, manufacturing and administrative centers. As was true with the dynasties the Song Dynasty was essentially ruled by an elite bureaucracy chosen through competitive examinations on classic Confucian texts. Some 20,000 mandarins were responsible for governing an empire with more than 100 million people. Progress was hampered somewhat by strong central control. Fearing loss of authority, the bureaucracies reigned in the power of merchants with strict regulations.

Scholar-Officials During the Song Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Song period saw the full flowering of one of the most distinctive features of Chinese civilization — the scholar-official class certified through highly competitive civil service examinations. Most scholars came from the landholding class, but they acquired prestige from their learning and political clout by serving in office. In a society in which most people were illiterate, scholar-officials stood out by virtue of their reading and writing skills. Their Confucian education encouraged them to aspire for government service, but also to speak up when they thought others were pursuing the wrong course, making them courageous critics of power. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Song period saw the full flowering of one of the most distinctive features of Chinese civilization — the scholar-official class certified through highly competitive civil service examinations. Most scholars came from the landholding class, but they acquired prestige from their learning and political clout by serving in office. In a society in which most people were illiterate, scholar-officials stood out by virtue of their reading and writing skills. Their Confucian education encouraged them to aspire for government service, but also to speak up when they thought others were pursuing the wrong course, making them courageous critics of power. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“The officials of the Song dynasty approached the task of government with the inspiration of a reinvigorated Confucianism, which historians refer to as “Neo-Confucianism.” As with any group of scholars and officials, different individuals had different understandings of just what concrete measures would best realize the moral ideals articulated in “The Analects” and Mencius. Such disagreements could be quite serious and could make or unmake careers.

Success as a scholar-official was often defined in terms of knowledge on the Five Confucian Classics — 1) Classic of Poetry (Shijing); 2) Classic of History (Shujing); 3) Classic of Changes (Yijing); 4) Record of Rites (Liji); and 5) Chronicles of the Spring and Autumn Period (Chunqiu)— and The Four Books — 1) The Great Learning (Daxue); 2) The Doctrine of the Mean (Zhongyong); 3) The Analects of Confucius (Lunyu); and 4) The Mencius (Mengzi).

Scholar-Officials and the Chinese Emperor

The highest position in the scholar-bureaucracy was occupied by the prime minister, who, because he had risen by merit from the common people, was viewed as "a check on the whims of the Emperor and on the influence of the palace clique." During the Ming dynasty the power of the emperor was strengthened by giving him the power to dismiss any prime minister who opposed him.

Messages sent with the bureaucracy were sealed memorials delivered at lightning speed. They took the form of communications between officials of equal rank, bonds, communications between government offices, statements, dispatches, memorials to the Throne, registers, career records and other documents. It was a Chinese tradition that senior scholar-officials make their views known by praise or condemnation of a piece of literature; it was a favorite tactic of Mao's.

Practitioners of Confucian values, the Emperors and the ruling class thumbed their noses at the merchant class and rebuffed Western attempts at trade.

Education and Governmental Responsibility

Qing Emperor Kangxi with a brush in hand

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “ Perhaps the greatest irony of the civil service examination system in China is that in many respects, despite the praiseworthy principle of appointment by competitive examination, the system was defective because the exams tested students for the wrong skills. It was a fundamental tenet of the time that mastery of Confucian moral texts, of poetic forms, and of the rhetoric of canonical commentary uniquely equipped a man to govern others. To us, it seems self-evident that this is not true. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

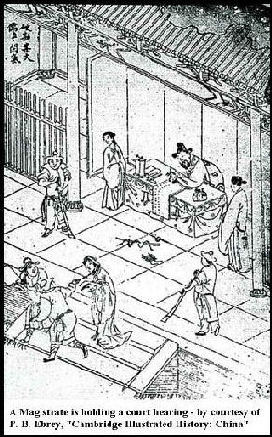

“Successful graduates of the exam system faced certain immediate problems to which they were ill suited to respond. Graduates were often posted to low level positions in the provinces where they assumed duties at the level of the county magistrate. There, they were responsible for such duties as tax collection, water conservation, agricultural enhancement, legal administration, and management of their own county offices, called yamen. Typically, they faced certain handicaps. First of all, their jurisdictions generally extended over populations of perhaps forty to fifty thousand people, and they were supplied with no assistance from the central government. Magistrates were responsible for hiring yamen staff from local people. Because there was a “rule of avoidance” that ensured that no official would ever be appointed to a post in his home district (to avoid problems of favoritism), a new officer from the capital would be entirely unfamiliar with the population from which he had to select his assistants. Frequently, when young men were posted far from their home counties, they were not even able to understand the local dialects of the people they governed! Moreover, the budget of a magistrate was a very limited one..his salary was small and he was provided with virtually no discretionary funds. /+/

“Basically, young men fresh from their Confucian studies were completely untrained in the skills that would allow them to succeed under such conditions unless they had received informal instruction from family members or acquaintances who had been immersed in government. It was quite common for such men to govern incompetently. Some resorted to brutal authoritarian measures, others exhausted themselves issuing moral proclamations urging their people to behave properly (not a very effective strategy). Most often, magistrates fell under the influence of powerful local families, who provided them with “officers” who were skilled in using coercion to extract taxes from peasants and confessions from “criminals.” By relying on such local bullies, a magistrate could ensure that he could forward to the central government the revenues the emperor demanded and that he could submit records of court proceedings demonstrating his sagely ability to bring the guilty to justice and keep order in his district. Inevitably, such patterns of conduct also involved habits of bribery and other forms of corruption that were endemic in the Chinese political system (and remain so today). /+/

“Periodically, there were reform initiatives that proposed to make the contents of the exams more relevant to the practical skills necessary for government. But these movements were rarely successful. The men who occupied high office and served as the examiners of the next generation had invested their entire identities in the education of their youth..they were not likely to approve of any radical change in standards or content to the exams. In most cases, the most revolutionary changes merely involved the authorization of a more “modern” or pragmatically oriented set of commentaries to the Confucian classics than those that had been employed previously. While in some cases this might have allowed examiners to give added weight to answers that suggested some grasp of the intricacies of practical governance, this was not always the result. The fourteenth century certification of the commentaries of the great Neo-Confucian philosopher Zhu Xi’s as orthodox resulted in the opposite result. Zhu Xi was a brilliant metaphysician..his theories of the cosmos and its relation to man’s ethical tendencies represent a wonderful example of philosophical imagination – but when successful candidates sought to apply Zhu’s cosmic theories of Heavenly Principle, material force, and the moral intuitions of the sage heart to the problems of tax collection, flood control, and militia organization, they sometimes found that he was a little sketchy on the details.” /+/

Competence and Corruption Among Scholar-Officials

Qianlong Emperor doing calligraphy

Dr. Eno wrote: “As we have noted before, while the Han Dynasty decision to credential officers of state through a system of Confucian education ensured that government was directed by literate and generally thoughtful men, chosen on the basis of merit, the nature of the Confucian curriculum meant that these officials were not often trained to address directly the practical concerns of governance. These matters included both the demands directly made by the imperial Legalist state, including tax collection and law enforcement, and also a range of issues that varied according local needs: agriculture and water conservancy, maintenance of commercial roads or waterways, supervision of market practices, and so forth. These were not matters that were covered in any detail in the Confucian curriculum. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“Although all Chinese governments exercised the absolute power that Legalism prescribed, against which subjects had little or no defense, the degree to which the government controlled society was, in fact, significantly limited by the size of the centrally appointed government, which was actually quite small by modern standards. Although there was a lavish court establishment, much of it staffed by imperial favorites, eunuchs, and others who were not products of the exam system, the actual number of men who were appointed to official position with jurisdiction over the subjects of the realm was generally in the neighborhood of forty thousand. This group of men, exam graduates, aspired to high office in the central government at the capital, but their initial postings, and for many, the only type of appointment they received, were to serve as local “magistrates,” that is, as the sole representatives of the central government in the thousands of small counties of China. From these positions, they might rise to higher status on the local level, for example, a “prefect,” who administered a major urban center or cluster of rural counties, or to a major appointment outside the capital as a provincial governor – and of course, most hoped to rise to positions at the capital. However, the key representatives of the government were truly the lower.level local magistrates – they did not set policy, but they had to implement it, and do so in a way that was responsive to local needs. /+/

“Apart from the fact that their Confucian training provided the men who served as magistrates with few tools to respond to the practical needs of office, there were other major obstacles to success. In order to guard against corruption, there was an inflexible “rule of avoidance” that forbade the appointment of any magistrate to the district from which he himself came. Consequently, many young exam graduates found themselves sent to a remote area of the empire, where they were unfamiliar with the people, the customs, and often even with the spoken language. There, without any other officers of state in their district, they attempted to manage the yamen (magistrate’s office), coordinate the police, manage tax collection, act as investigator and judge in criminal and civil court cases, and administer a range of other tasks that varied with their district. /+/

“Obviously, this was not a task a single person could accomplish without help, and, indeed, the government included in the salary of the magistrate funds to hire a yamen staff and police force that could implement his orders. Unfortunately, there was no exam system for these appointments, and little way for a magistrate to determine which men of his district were appropriate for these appointments. Magistrates served in their district for only a few years at a time, and as they rotated, they tended to retain the staff hired by their predecessors. But where did these “ yamen runners” come from. /+/

“Basically, the staff of the yamen was drawn from or recommended by the most powerful families in the district. These were generally landholding families, often called “gentry,” who had amassed wealth and local prestige through merchant activities, association with government officials – sometimes their own sons were exam graduates – or successful careers in various criminal activities. All too often, especially in rural districts, local society was dominated by families who used their wealth and reputations to bully the peasants and coerce from them high rents for land, various tribute payments, and unpaid forms of service. When a magistrate arrived to represent the central government, he was, in a sense, in competition with a local power structure that was designed not to serve the government, but to serve the local elite. And the staff he was provided with to help him compete with the local elite was often put forward by and beholden to that same local elite. Frequently, local families underwrote the costs of hiring personnel, since the magistrate’s funds were very limited, and it was in the interest of the families to have their agents infiltrate the yamen. /+/

“Consequently, there were two basic types of gaps that existed at the level of local government, where imperial policy was most directly implemented. First, the training of the officers of state did not closely match the practical challenges of governance that they faced. Second, the personnel who comprised what we call the “subbureaucracy” was not aligned with the goals of the state, and were often, in fact, agents of a corrupt local power structure. /+/

“As the Cultural Confucians continued to raise the standards of classical scholarship demanded by the exams that qualified men for government service, the consequence was that the men who succeeded in earning government appointment were increasingly well screened for intelligence and ambition, but increasingly less familiar with the practical and technical aspects of society that they would be called upon to address once their quest for appointment was successful. /+/

Selections from “Meritorious Deeds at No Cost: Scholars”

Song-era government seal

According to Buddhism and to some degree Confucianism (people Neo-Confucianism, which incorporates Buddhist elements) and other religions practiced in China achieving merit in one’s lifetime was key to achieving a better life next time around. The following document from the 17th century — “Meritorious Deeds at No Cost” — offers tips on acquiring merit aimed at particularly classes of people. [Source: “ from “Meritorious Deeds at No Cost” from “Sources of Chinese Tradition,” compiled by Wm. Theodore de Bary and Irene Bloom, 2nd ed., vol. 1 (New York: Columbia, University Press, 1999); Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

Selections from “Meritorious Deeds at No Cost: Scholars”: “1) Be loyal to the emperor and filial to your parents. 2) Honor your elder brothers and be faithful to your friends. 3) Establish yourself in life by cleaving to honor and fidelity. 4) Instruct the common people in the virtues of loyalty and filial piety. 5) Respect the writings of sages and worthies. 6) Be wholehearted in inspiring your students to study. 7) Show respect to paper on which characters are written. 8) Try to improve your speech and behavior. 9) Teach your students also to be mindful of their speech and behavior. 10) Do not neglect your studies without reason.

“11) Do not despise others or regard them as unworthy of your instruction. 12) Be patient in educating the younger members of poor families. 13) If you find yourself with smart boys, teach them sincerity, and with children of the rich and noble, teach them decorum and duty. 14) Exhort and admonish the ignorant by lecturing to them on the provisions of the community compact and the public laws. 15) Do not speak or write thoughtlessly of what concerns the women’s quarters. 16) Do not expose the private affairs of others or harbor evil suspicions about them. 17) Do not write or post notices that defame other people. 18) Do not write petitions or accusations to higher authorities. 19) Do not write bills of divorce or separation. 20) Do not let your feelings blind you in defending your friends and relatives.

“21) Do not incite gangs (bang) to raid others’ homes and knock them down. 22) Do not encourage the spread of immoral and lewd novels [by writing, reprinting, expanding, and so on]. 23) Do not call other people names or compose songs making fun of them. 24) Publish morality books in which are compiled things that are useful and beneficial to all. 25) Do not attack or vilify commoners; do not oppress ignorant villagers. 26) Do not deceive the ignorant by marking texts in such a way as to overawe and mislead them. 27) Do not show contempt for fellow students by boasting of your own abilities. 28) Do not ridicule other people’s handwriting. 29) Do not destroy or lose to books of others. … To those of some understanding explain the teachings of the Cheng.Zhu school; to the uneducated give books on moral retribution. 30) Make others desist from unfiliality toward their parents or unkindness toward relatives and friends. 31) Educate the ignorant to show respect to their ancestors and live in harmony with their families.”

Wang Anshi: the Reformist Scholar-Official

Wang Anshi

Wang Anshi (1021-1086) is one of China's most scholar-officials. Known as a reformers, he qualified at age 21 as an "advanced scholar" in the civil service examinations and wrote a 10,000-word memo to Emperor Rensong in 1058 arguing that China's officials were not fit for purpose, and needed better training. Appointed as privy counsellor in 1067, he launched "new policies" that included government loans for farmers and stimulating the economy by minting coins. He irritated conservatives by carrying out a land survey to reassess property taxes and doing away with recitation of classics and poetry composition in the civil service exams. Instead he put an emphasis on law, medicine and military science. Wang resigned in 1074, returned to civil service in 1075, then retired for good in 1076 to write poetry [Source: Encyclopaedia Britannica]

Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: “The behaviour and competence of China's bureaucrats have defined the state for 2,000 years. But in the 11th Century came a visionary who did something almost unheard of - he tried to change the system. For the first 50 years of his life everything Wang Anshi touched turned to gold. To begin with, he came fourth in the imperial civil service exam - quite an achievement, as Frances Wood, curator of the Chinese collection at the British Library explains: "To come in fourth in the whole of China… think of the size of China. To come fourth out of thousands? Tens of thousands of people? It's absolutely massive." [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, October 17, 2012 \=]

“The successful Wang Anshi was sent off to administer a southern entrepreneurial city. You can imagine him on an inspection tour, peering out through the silk curtains of his sedan chair at the stallholders and hawkers. But after 20 years of this, it was clear to him that writing essays about Confucian virtue just wasn't relevant any more. A civil servant needed a different skill set." \=\

Wang Anshi's Reforms

At a time when the Song Dynasty was experience economic and foreign policy problems, Wang Anshi proposed a new style of government. "The pressure of hostile forces on the borders is a constant menace. The resources of the Empire are rapidly approaching exhaustion, and public life is getting more and more decadent," he wrote to the emperor. "There never has been such a scarcity of capable men in the service of the State. Even if they should go on learning in school until their hair turned grey, they would have only the vaguest notion of what to do in office...No matter how fine the orders of the Court, the benefit is never realised by the people because of the incapacity of local officials. Moreover, some take advantage of these orders to carry on corrupt practices," said Wang Anshi. [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, October 17, 2012 \=]

Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: “In 1067 a young emperor came to the throne, hungry for new ideas, and Wang Anshi got his chance. Once in the top ranks of the civil service, Wang Anshi set about diluting Confucius and surrounding himself with like-minded men. Morality was out, maths and medicine were in. "He was trying to reform the examination system," says Xun Zhou, a historian at Hong Kong university. "So he got rid of some of the subjects. He introduced more practical subjects, so that enabled people with practical skills into the government. And once they were in, Wang Anshi asked them practical questions. How can we improve education? How can we improve agriculture? How can we provide credit to farmers? How can we ensure a flow of goods?” \=\

The civil service has a way of doing things, and in the 11th Century Wang Anshi was turning it upside down, asking the scholar-officials to roll up their sleeves and manage every corner of the economy. He wanted state loans for farmers, more taxes for landowners, centralised procurement. But he was not watching his back. He was too sure of himself and too focused on the big picture. \=\

Wang Anshi's Downfall and Legacy

Another rendering of Wang Anshi

Carrie Gracie of BBC News wrote: Then events - a drought and a famine - overtook him. It was the opportunity his rivals had been waiting for. "You have this clash between someone who is obviously very bright, very brilliant, and then he's faced with these corrupt people who've managed to buy their way in," says Frances Wood. As is often the case, the good man comes up against entrenched, corrupt bureaucrats who didn't want any changes and they turned the emperor against him." [Source: Carrie Gracie, BBC News, October 17, 2012 \=]

“Wang Anshi was not the type to compromise - getting other people on side was not his style. But added to that, it would have been dangerous to be seen building a faction. That way, in China, lies disaster. Scholar-officials c.1400 Officials have dominated Chinese life for centuries "If the emperor perceives that there's a group of people, a group can grow into something bigger, and I think it's almost more dangerous to be part of a group than it is to be a lone figure crying wolf," says Wood. "Because you're disgraced, but you can't be accused of being a conspirator."\=\

“So it's a difficult game to be a reformist in China. It's safer to stick with the prevailing wisdom, and keep your head down. Wang Anshi retired in 1076, depressed by demotion and the death of his son. He spent the final years of his life writing poetry. In the 20th Century some communists hailed him as an early socialist. But for nearly 1,000 years he was the black sheep of the bureaucracy, and the failure of his reform programme, a cautionary tale. "By and large, Wang Anshi remains an example of what not to do," says Bol. "There is this radical turn against increasing the state's role in society and the economy. And it doesn't happen again until the 20th Century. "Because in the 20th Century, the communists picked up some of Wang Anshi's ideas again and rescued his reputation." \=\

Career of a District-Level Scholar-Official in 19th Century China

In 1899, Arthur H. Smith wrote in “Village Life in China”: “At any part of the long process which we have described, it is possible to become a candidate for honours above, by purchasing those below. A man of real talent, studiously inclined, might for example buy the rank of ling-shêng, and then with a preceptor of his own, and great diligence, become a kung-shêng, a chü-jên, and perhaps at last an official, skipping all the tedious lower steps. The taint of having climbed over the wall, instead of entering by the straight and narrow way, would doubtless cling to him forever, but this circumstance would probably not interfere with his equanimity, so long as it did not diminish his profits. As a matter of experience, however, it is probable that it would be more worth while to buy an office outright, rather than to enter the field, by the circuitous route of a combination of purchase and examinations. [Source: “Village Life in China” by Arthur H. Smith, Fleming H. Revell Company, 1899, The Project Gutenberg]

“The office of Superintendent of Instruction, is considered a very desirable one, since the duties are light, and the income considerable. This income arises partly from a large tract of land set apart for the support of the two Superintendents, partly from “presents” of grain exacted twice a year after the manner of Buddhist priests, and partly from fees which every graduate is required to pay, varying as all such Chinese payments do, according to the circumstances of the individual. The Superintendent is careful to inquire privately into the means at the disposal of each graduate, and fixes his tax accordingly. From his decision there is no appeal. If the payment is resisted as excessive, the Superintendent, who is theoretically his preceptor, will have the hsiu-ts‘ai beaten on the hands, and probably double the amount of the assessment. If any of the graduates in a district are accused of a crime, they are reported to the District Magistrate, who turns them over to the Superintendent of Instruction, for an inquiry. The Superintendent and the Magistrate together, could secure the disgrace of a graduate, as already explained.

“The Government desires to encourage learning as much as possible, and to this end there are in many cities, what may be termed Government high-schools or colleges, where preceptors of special ability are appointed to explain the Classics, and to hold frequent examinations, similar to those in the regular course, as described. The funds for the support of such institutions, are sometimes derived from the voluntary subscriptions of wealthy persons, who have been rewarded by the gift of an honourary title, or perhaps from a tax on a cattle fair, etc. Where the arrangement is carried out in good faith, it has worked well, but in two districts known to the writer, the whole plan has been brought into discredit of late years, on account of the promotion to office of District Magistrates who have bought their way upward, and who have no learning of their own. In such cases, the management of the examination is probably left to a Secretary, who disposes of it as quickly and with as little trouble to himself as possible. The themes for the essays are given out, and prizes promised for the best, but3 instead of remaining to superintend the competition, the Secretary goes about his business, leaving the scholars who wish to compete to go to their homes, and write their essays there, or to have others do it for them, as they prefer. In some instances, the same man registers under a variety of names, and writes competitive essays for them all, or he perhaps writes his essays and sells them to others, and when they are handed in, no questions are asked. It would be easy to stop abuses of this sort, if it were the concern or the interest of any one to do so, but it is not, and so they continue. A school-teacher with whom the writer is acquainted, happening to have a school near the district city, made it a constant practice for many years, to attend examinations of this sort. He was examined about a hundred times, and on four occasions received a prize, once a sum in money equivalent to about seventy-five cents, and three other times a sum equal to about half-a-dollar!

“It is a constant wonder to Occidentals, by what motives the Chinese are impelled, in their irrepressible thirst for literary degrees, even under all the drawbacks and disadvantages, some of which have been described. These motives, like all others in human experience are mixed, but at the base of them all, is a desire for fame and for power. In China the power is in the hands of the learned and of the rich. Wealth is harder to acquire than learning, and incomparably more difficult to keep. The immemorial traditions of the empire are all in favour of the man who is willing to submit to the toils that he may win the rewards of the scholar.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Mandarin. All Posters.com;

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University; ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated September 2022