YUAN DYNASTY CRAFTS

Buckle plaque with dragon and Ruyi scrolls

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Starting from the reign of Chinggis Khan, artisans of great skill were honored under the Mongols. For example, the craftsman Sun Wei (1183-1240) excelled at making armor. When even the arrow of Chinggis Khan could not pierce a piece of armor that Sun Wei had made, Chinggis honored him with the title "Yeke Uran" and ordered him as leader of the artisan command. In Mongolian, "Yeke Uran" means a great artisan or a craftsman with exceptional skill. Sun Wei's title was so valued that he even passed it on to his son Sun Kung-liang (1222-1300).” One story goes: “When the Great Khan picked up a piece of armor that his arrow could not pierce, he uttered in Mongolian to the artisan who made it, "Ah, you — Yeke Uran!" The artisan was greatly honored for this title, for he knew that the khan was referring to him as a great artisan.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The Mongols admired refined craftsmanship. When the Mongol armies conquered large parts of the Eurasian continent, they took the artisans they captured and placed them in art and craft workshops in various areas. For this reason, local techniques and styles spread far and wide as artisans of different cultural backgrounds influenced and interacted with each other. For example, the techniques of silk weaving and papermaking in China spread west as gold weaving techniques and astronomical knowledge from the Central Asia area spread into China. In this period of widespread cultural fusion, innovation in the arts and crafts was as great as the influence that it would have on later generations. \=/

“The culture of the Mongols is characterized by its multi-faceted, pluralistic features. Gold works, Buddhist sculptures, ritual objects and certain patterns on ceramics exhibition all reveal a strong affinity to Tibet and Islam. That porcelains of some of the major kilns of China have been discovered in Inner Mongolia serves to confirm that trade between the north and south was common during the Mongol Empire and Yuan Dynasty. \=/

Good Websites and Sources: on the Mongols and Yuan Dynasty Wikipedia Yuan Dynasty Wikipedia ; Mongols in China afe.easia.columbia.edu Mongols Wikipedia Wikipedia ; Mongol Empire allempires.com ; Wikipedia Kublai Khan Wikipedia ; Kublai Khan notablebiographies.com ; Chinese History: Chinese Text Project ctext.org ; 3) Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu ; Chaos Group of University of Maryland chaos.umd.edu/history/toc ; 2) WWW VL: History China vlib.iue.it/history/asia ; 3) Wikipedia article on the History of China Wikipedia Ceramics and Porcelain: 1) China Museums Online: chinaonlinemuseum.com ; 2) Guide to Chinese Ceramics: Song Dynasty, Minneapolis Institute of Arts; artsmia.org features many examples of different types of ceramic ware produced during the Song dynasty, including ding, qingbai, longquan, jun, guan and cizhou. 3) Making a Cizhou Vessel Princeton University Art Museum artmuseum.princeton.edu. This interactive site shows users seven steps used to create Song- and Yuan-era Cizhou vessels.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; GENGHIS KHAN AND THE MONGOLS factsanddetails.com; YUAN (MONGOL) DYNASTY (1215-1368) AND THE MONGOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; YUAN DYNASTY LIFE AND ECONOMICS factsanddetails.com; YUAN DYNASTY CULTURE, THEATER AND LITERATURE factsanddetails.com; YUAN ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY factsanddetails.com; KUBLAI KHAN AND CHINA'S YUAN DYNASTY (1215-1368) factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO'S DESCRIPTIONS OF CHINA factsanddetails.com; MARCO POLO AND KUBLAI KHAN factsanddetails.com; MONGOL INVASION OF JAPAN: KUBLAI KHAN AND KAMIKAZEE WINDS factsanddetails.com CHINESE CERAMICS factsanddetails.com ; PORCELAIN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CELADONS factsanddetails.com ; JIANGDEZHEN AND ITS PORCELAIN, KILNS AND GLAZING AND PAINTING TECNIQUES factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The World of Khubilai Khan: Chinese Art in the Yuan Dynasty” by James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com; “Housing, Clothing, Cooking, from Daily Life in China on the Eve of the Mongol Invasion 1250-1276" by Jacques Gernet Amazon.com ;“The Urban Life of the Yuan Dynasty” by Shi Weimin, Liao Jing, Zhou Hui Amazon.com; “Khubilai Khan: His Life and Times” by Morris Rossabi Amazon.com ; “The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties” by Timothy Brook Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 6: Alien Regimes and Border States, 907-1368" by Herbert Franke and Denis C. Twitchett Amazon.com; Ceramics: “Chinese Ceramics: From the Paleolithic Period through the Qing Dynasty” by Laurie Barnes, Pengbo Ding, Jixian Li, Kuishan Quan Amazon.com “How to Read Chinese Ceramics by Denise Patry Leidy (The Metropolitan Museum of Art) Amazon.com; “Chinese Glazes: Their Origins, Chemistry, and Recreation” by Nigel Wood Amazon.com; Celadons: “Chinese Celadon Wares”by Godfrey St. George Montague. Gompertz Amazon.com “Ice and Green Clouds: Traditions of Chinese Celadon” by Yutaka Mino and Katherine Tsiang Amazon.com; Porcelain: “Illustrated Brief History of Chinese Porcelain” by Guimei Yang and Hardie Alison Amazon.com “Chinese Porcelain” by Anthony du Boulay Amazon.com; “Chinese Pottery and Porcelain” By Vainker ( Amazon.com ; Jingdezhen: “China's Porcelain Capital: The Rise, Fall and Reinvention of Ceramics in Jingdezhen” by Maris Boyd Gillette Amazon.com; “Jingdezhen Imperial Kiln Museum” by Zhu Pei Amazon.com; Art: “The Arts of China” by Michael Sullivan and Shelagh Vainker Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: A Guide to Motifs and Visual Imagery” by Patricia Bjaaland Welch Amazon.com; “Chinese Art: (World of Art) by Mary Tregear Amazon.com; “Possessing the Past: Treasures from the National Palace Museum, Taipei” by Wen C. Fong, and James C. Y. Watt Amazon.com ; “The British Museum Book of Chinese Art” by Jessica Rawson, et al Amazon.com; “Art in China (Oxford History of Art) by Craig Clunas Amazon.com

Yuan Influences

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “High culture was traditionally maintained in China by the scholar-official class, but the refined literary pursuits of cultivation and leisure also influenced the educated members of Mongol and other ethnic groups in the Yuan dynasty. However, in terms of arts and crafts, the establishment of the National School and academies across the land inspired a revivalist style in the production of bronzes and ceramics. Furthermore, with a rich supply of jade at its source, Chinese jade craftsmen and Central Asian gold artisans were also able to combine their creative energies under the Mongols to produce intricate openwork jade.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

“Many of the techniques used in arts and crafts during the Ming and Ch'ing dynasties were established in the previous Yuan dynasty under the Mongols. For example, designs painted in underglaze blue and underglaze red rose in the Yuan dynasty and flourished in the Hung-wu, Yung-lo, and Hsuan-te reigns of the following Ming dynasty. The import of "Tadjik ware" from the Middle East greatly influenced the aesthetics of cloisonne enamelware in the Hsuan-te and Ching-t'ai reigns. Chinese lacquer ware was renowned in foreign lands during the Yuan dynasty and inspired the famed carved lacquer wares produced in the Yung-lo reign. \=/

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “In the fine arts, foreign influence made itself felt during the Mongol epoch. This was due in part to the Mongol rulers' predilection for Tibetan Buddhism, which developed as a fusion between traditional Tibetan shamanism (Bon) and Buddhism. During the rise of the Mongols this religion, which closely resembled the shamanism of the ancient Mongols, spread in Mongolia, and through the Mongols it made great progress in China, where it had been insignificant until their time. Religious sculpture especially came entirely under Tibetan influence (particularly that of the sculptor Aniko, who came from Nepal, where he was born in 1244). This influence was noticeable in the Chinese sculptor Liu Yuan; after him it became stronger and stronger, lasting until the Manchu epoch. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“In architecture, too, Indian and Tibetan influence was felt in this period. The Tibetan pagodas came into special prominence alongside the previously known form of pagoda, which has many storeys, growing smaller as they go upward; these towers originally contained relics of Buddha and his disciples. The Tibetan pagoda has not this division into storeys, and its lower part is much larger in circumference, and often round. To this day Beijing is rich in pagodas in the Tibetan style.

Examples of Yuan Dynasty Crafts

Lacquer

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Although the technique of openwork jade carving was practiced as early as the late Neolithic, jade carvers even as late as the Sung and Liao dynasties were not able to develop a technique for multi-level openwork design. However, it began to appear in the Yuan dynasty. First it was two- and three-level designs that gradually developed into even more intricate ones for a truly three-dimensional effect. Yuan dynasty jade artisans were thus able to combine surface and openwork techniques to develop multi-level carved jades. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Textile with Griffins, Lampas weave, silk: The Mongols established three centers of textile production through the forced relocation of workers under Genghis Khan and his son and successor Ögödei (reigned 1229–41). Many of these artisans were conscripted from eastern Iranian cities such as Herat, in Khurasan [map], which had been renowned for its silk and gold cloth. Textiles such as this remarkable woven panel adorned with griffins illustrate the resulting blend of motifs and styles. While the griffin motif is better known in West rather than East Asian art, the creatures’ curvaceous, scroll-like wings and tails in this textile suggest an influence from east of the Iranian world. The main decoration is a repeat design of lobed medallions enclosing a pair of rampant addorsed griffins with heads turned back to face one another. The medallions are set against a pattern of hexagons each bearing a rosette formed from seven circles.The borders, which are woven in one piece with the main pattern, are decorated with a scrolling peony design. This piece belongs to the Inner Mongolia Museum, Hohhot. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of Seal in Phagspa Script, bronze (height: 7.5 centimeters, width: 6.4 centimeters): This square seal in Phagspa script has a trapezoidal knob. The face of the seal is carved in three rows of Phagspa seal script with the name of an official title, indicating it belonged to a commanding officer of the Yuan imperial armies. The top is carved in Chinese with the corresponding official title in regular script as well as the bureau that manufactured it (Ministry of Rites) and the date, which corresponds to 1287 and thus puts it during the reign of the Mongol ruler Kublai Khan in the Yuan dynasty of China. This belongs to the Museum of Inner Mongolia (Hohhot). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Mongol Symbols in Chinese Art

Ilkanate silk

Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ In the creation of luxury textiles and objects for the Mongol elite, Chinese artists developed a visual language that was an effective means of establishing their rule and consolidating their presence throughout the vast empire. A number of motifs that were part of the existing artistic repertoire were adopted as imperial symbols of power and dominance—the dragon and the phoenix, for example, two mythical beasts that integrated the ideas of cosmic force, earthly strength, superior wisdom, and eternal life. The Mongol versions of the creatures are the highly decorative sinuous dragon with legs, horns, and beard and the large bird with a spectacular feathered tail floating in the air. In Iran, these motifs were often paired and became so popular with the Ilkhanids that they eventually lost their original meaning, becoming part of the common artistic repertoire in the first half of the fourteenth century. [Source: Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Other motifs of this period that were familiar throughout the Asian continent are the peony, the lotus flower, and the lyrical image of the recumbent deer, or djeiran, gazing at the moon. The flowers, often seen in combination and viewed from both the side and top, provided ideal patterns for textiles and for filling dense backgrounds on all kinds of portable objects. The djeiran became widespread in the decorative arts because of the well-established association of similar quadrupeds with hunting scenes."^/

“For the semi-nomadic Mongols, portable textiles and clothing were the best means of demonstrating their acquired wealth and power, so it is reasonable to assume that the main mode of transmission of motifs such as the dragon and peony was through luxury textiles. The most prominent clothing accessories were belts of precious metal (gold belt plaques, The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art). Many of the textiles illustrated here prove transmission from east to west, yet in some instances, exemplified by the Chinese silk with addorsed griffins (cloth of gold: winged lions and griffins, The Cleveland Museum of Art), the origin of the image is clearly Central or western Asia. The Mongol period is unique in art history because it permitted the cross-fertilization of artistic motifs via the movement of craftsmen and artists throughout a politically unified continent."^/

Mongol-Chinese- Yuan Crafts with Phoenixes

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Canopy with Phoenixes, China, Yuan dynasty (1271–1368), Embroidery, silk and gold thread: With its lavish use of raised gold threads, this embroidered silk canopy demonstrates the Chinese taste for luxurious textiles during the Yuan dynasty. The dynamic radial composition of two phoenixes circling in flight is enhanced by the bird’s curved wings and elaborate plumage. Such motifs were popular in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, where they were used in a variety of media, such as the carved lacquer tray here. The same type of design is found in early-fourteenth-century Iran among the so-called Sultanabad wares (such as the Bowl with Four Phoenixes shown here); it is likely to have derived from the Chinese motif, with textiles such as this one serving as a means of transmission. This piece belongs to the The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Lacquer Tray with Phoenixes, Southern Song dynasty (1127–1279), Red, yellow, and black lacquer on wood: In China, objects made from lacquer—a seemingly humble material produced from tree sap—were, in fact, highly prized luxury goods. Carved lacquers such as this finely detailed tray, for example, could require the application of hundreds of layers of lacquer, and take over a year to complete. The tray's motif of paired phoenixes, arranged in a circular configuration, became a common theme under the Chinese Yuan dynasty (1271–1368) and in Ilkhanid Iran in a variety of media, including ceramics. The opposed phoenixes in flight are set among flowers representing each of the four seasons: 1) winter, plum blossoms; 2) spring, peonies; 3) summer, lotuses; 4) autumn, chrysanthemums. This piece belongs to the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington D.C.

Yuan Period Buddhist Tapestries and Thankas

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of Hevajra, (originally ascribed as a Yuan Mahakala tapestry): “Hevajra is one of the five main deities in Tibetan Buddhism. A believer could choose any Buddha, bodhisattva, or protector as a "principal deity" of worship and practice throughout life. The popularity of Hevajra was mainly due to the faith of Kublai Khan. It was in 1253 that Kublai Khan and his consort Chabi were converted to Buddhism by Tibetan high monk Phagspa. They received the tantric baptism of Hevajra as practiced in the Sakya sect of Phagspa. In the personification of Buddhist ideals and practices, Hevajra stood for wisdom and compassion as well as the overriding power of Buddhism. Thus, Hevajra is shown here trampling on four figures to symbolize overcoming one's difficulties. \=/ [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/]

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of a thanka of Onpo Lama Rimpoche, (Fourth Abbot of the Taklung Monastery), 13th century: The Taklung Monastery, the main monastery of the Taklung Sect, is situated 65 kilometers north of Llasa. In 1240, the Mongol general Godan sent To-ta to Tibet in preparation for an assault. To-ta returned and informed him that "Monks of the Taklung monastery are of the highest morals." Indeed, the two Taklung thankas in this exhibit have inscriptions on the reverse that emphasize the importance of the virtues of "restraint" and "perseverance" for monks. For this reason, Taklung clergy were respected by the Yuan imperial precept Phagspa and received the patronage of Kublai Khan. Buddhists revere the "Three Treasures" of the Buddha, the Law, and the clergy. Most of the surviving portraits from the Yuan dynasty are from the Taklung Monastery, which established a norm and a didactic model for posterity. \=/

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of “Amitabha Buddha, Sung to Yuan Dynasty: “In the 13th century, as Genghis Khan was commanding his armies to the north, the Buddhist holy land of India came under the control of Muslim leaders. The last classic phase of Indian Buddhist art from the Palas dynasty (750-1200) reveals the classic elegance and introversion of Gupta (5th century) art with the decorative and delicate esoteric features of East Indian art. Fortunately, the Palas tradition was preserved in Nepal and Tibet. But what exactly is the East Indian Palas style? The figure in this work is elegant and the coloring clear. This work is representative of a thanka from the Kadam sect of central Tibet.” \=/

“The Mongols also developed in China the art of carpet-knotting, which to this day is found only in North China in the zone of northern influence. There were carpets before these, but they were mainly of felt. The knotted carpets were produced in imperial workshops—only, of course, for the Mongols, who were used to carpets. A further development probably also due to West Asian influence was that of cloisonné technique in China in this period. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

Yuan Sculpture

Buddha relief

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of a dragon protome, second half of the 13th century, White marble: This impressive dragon’s head, which is both a decorative and a protective figure, embellished one of the buildings at Shangdu (“Xanadu”) [map], the summer capital that Kublai Khan completed in 1258. This type of architectural decoration became popular throughout the Mongol empire in Asia, as indicated by similar objects found in the former territories of the Golden Horde. The L-shaped, roughly carved rear section of the stone was set into the wall, securing the finely carved head of a hornless dragon. ; This piece belongs to the Inner Mongolia Museum, Hohhot. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of a stone cenotaph, 14th century: “This cenotaph, or grave marker, which was found near the city of Chifeng in Inner Mongolia. demonstrates the presence of Muslims among the upper echelons of Chinese society under the Yuan dynasty. Dramatic clouds and large peonies fill the larger bands on the sides, vegetal scrolls with peonies and lotuses are carved inside narrower bands below, and lotus or peony flowers seen from above are shown in the vertical bands at both ends of the cenotaph. The top is also decorated with dense vegetal patterns. This piece belongs to the Inner Mongolia Museum, Hohhot. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

Yuan Ceramics and Porcelain

With the invention of underglaze blue porcelain in the Yuan period (1271-1368), Jingdezhen in Jiangxi province made itself the pre-eminent center for porcelain production, a position it held throughout the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. Celadon and white porcelain were superseded by porcelain with decoration painted under or over the glaze and by various wares with monochrome glazes. Porcelain decoration became richer and more colorful than ever before. [Source: Shanghai Museum, shanghaimuseum.net]

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: In the Yuan dynasty (1279-1368) Jingdezhen became the center of porcelain production for the entire empire. Most representative of Yuan dynasty porcelain are the underglaze blue and underglaze red wares, whose designs painted beneath the glaze in cobalt blue or copper red, replaced the more sedate monochromes of the Song Dynasty. At the same time, from the standpoint of the shape of the objects, Yuan dynasty porcelains became thick, heavy, and characterized by great size, transforming the refinement of Song Dynasty shapes. From this we can get some idea of the differences between the eating and drinking customs of the Sung and Yuan dynasties. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei, npm.gov.tw]

During the Song, Jin and Yuan dynasties from the tenth to fourteenth centuries, the firing of stoneware are widespread. Famous stonewares were named after the locations at which they were produced. Various kilns in different places came to establish their own independent styles as each excelled in the forms, glazes, skills for decorating and techniques of production for which they became known.

“The centers of white-ware production during this period were the Ding kilns located in Hebei province of the north and the Jingdezhen kilns in Jiangxi province of the south. The former produced an ivory-white glaze while the latter created shadowy blue glaze. Wares from both places were known for their fluidly-carved decorative motifs and patterns created by impressing molds onto the clay body. As for black ware, Jian ware produced in Fujian province enjoyed the greatest reputation, with the crystallized streaks in the glaze appearing like the hairs of a hare. The center of multi-colored ware production was at the Jun kilns in Henan province, the glazes exhibiting various shades of blues and violets on milky-green base colors. Furthermore, many kilns also applied various ferric oxides as a coloring agent, producing celadons in different shades of light green or blue. For example, Yaozhou kilns made olive-green ware, Ru kilns created sky-blue glazes, and Guan (Official) and Longquan kilns produced pastel-green and plum-green wares, respectively. Stonewares of the period feature plain but elegant glazes as well as simple and archaic forms. Many of the decorative patterns are inspired by daily life and nature. These stonewares were much appreciated by nobility, the general public and even foreign markets. Works are generally categorized based on the color of glaze, the location where made and the date of production. The objects are grouped as white, black, celadon and multi-colored ware.

The world record price paid for an art work from any Asian culture is $27.8 million, paid in March 2005 for a 14th century Chinese porcelain vessel with blue designs painted on a white background. The vessel contains scenes of historical events in the 6th century B.C. and has unique Persian-influenced shape. Only seven jars of this shape exist in the world. The buyer was Giuseppe Eskenazi., the renowned dealer of Chinese art, acting on behalf of a client. The previous record for porcelain was $5.83 million paid for a14th-century blue-and-white porcelain vessel called the pilgrims vessel in September 2003.

Colors and Glazes Used Yuan Ceramics

In the Yuan Dynasty floral motifs and cobalt blue paintings were made under a porcelain glaze. This was considered the last great advancement of Chinese ceramics. The cobalt used to make designs on white porcelain was introduced by Muslim traders in the 15th century. The blue-and-white and polychrome wares from the Yuan Dynasty were not as delicate as the porcelain produced in the Song dynasty. Multi-colored porcelain with floral designs was produced in the Yuan dynasty and perfected in the Qing dynasty, when new colors and designs were introduced.

In the Yuan Dynasty floral motifs and cobalt blue paintings were made under a porcelain glaze. This was considered the last great advancement of Chinese ceramics. The cobalt used to make designs on white porcelain was introduced by Muslim traders in the 15th century. The blue-and-white and polychrome wares from the Yuan Dynasty were not as delicate as the porcelain produced in the Song dynasty. Multi-colored porcelain with floral designs was produced in the Yuan dynasty and perfected in the Qing dynasty, when new colors and designs were introduced.

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The Mongols themselves originally did not have a tradition of ceramic vessels. In Yuan China, however, the ceramics produced under the Mongols continued to follow in distinct lines of development. The once quite popular wares of the Ting kilns in Hebei and those from the Yao-chou kilns in Shaanxi waned in the Yuan, while the opulent blue and purple glazes of Chun ware and the painterly ones from Tz'u-chou kilns gained wide popularity. Official kilns were established at Ching-te-chen in Kiangnan (in the south), and Lung-ch'uan wares rose in popularity due to export demand. The official ware types of the Southern Sung, however, were still preferred by the scholar class. Nonetheless, a distinct taste for opulent colors and painterly lines gradually appeared at this time. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“Vivid and colorful ceramics became the focus in pottery. Chun ware featured cooper-red haloes of glaze, Tz'u-chou ware featured peacock-blue glaze from the Middle East covering ceramics with black flower designs, and Ching-te-chen potters developed underglaze blue and underglaze red ceramics. These dynamic styles differ greatly from the pristine monochrome glazes works appreciated in the upper classes of previous periods. More importantly, these ceramic styles along with deeply carved lacquer wares and colorful cloisonne reflect important trends that would take place in post-Yuan arts and crafts. \=/

Types of Yuan Ceramics

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: 1) Chun Ware: “The body of Chun ware is thick and covered with an impure glaze. However, the effective control of sky blue glaze produces a rough yet warm effect produced in the sky blue glaze. With the skillful application of copper red pigments, the splashes and dots fuse to create a brilliant display of colors and patterns. Yuan dynasty Chun wares were quite popular and kilns were scattered over northern China and even imitated beyond China and in the south.” [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

2) “Ting Ware: “The Ting kilns, located in Ch'u-yang County of Hebei province, served as the center of white ceramic production in north China. The quality white wares became renowned through the land. Production flourished from the late T'ang to the Chin dynasty but diminished in the early Yuan dynasty. The Ting ware in this exhibit still reveals delicate molded patterns, but the body and glaze do not reflect the quality found in previous periods.” \=/

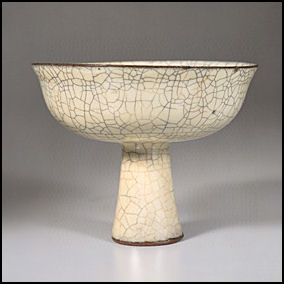

3) “Ko Ware: “Ceramics in imitation of official (Kuan) ware from the Southern Sung are often found in tombs and burials of the late Yuan dynasty. The glaze is more grayish-green and they bear clear linear decoration and deep crackling similar to collection examples of so-called "Ko ware". In the late Yuan, this type was referred to as Ko-ko Cave ware and may have been fired in the Hangchow vicinity or at Lung-ch'uan. It apparently reveals a kind of nostalgia in the Yuan dynasty for the aesthetic features of Southern Sung ceramics.” \=/

4) “Lung-ch'uan Ware Starting from the Southern Sung period, the Lung-ch'uan kilns provided wares to supply domestic and foreign demand. With kilns centered in Lung-ch'uan County of Zhejiang province, production locations eventually spread to include Jiangxi, Fukien, and Guangdong provinces for a style that covered many areas. Lung-ch'uan celadons of the Yuan dynasty are often large dishes, bowls, vases, and jars covered with a warm and dark-green glaze and with complex carved, engraved, and impressed patterns.” \=/

Yuan Ceramic Decoration

Porcelain pillow with scene from popular drama

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “The flourishing pluralism of Yuan dynasty culture inspired new forms and decoration in the arts and crafts. Stem cups and small cups reflected new habits of drinking at the time, and stringed-bead patterns and rhombic designs were closely related to the decoration of Mongolian clothing. Egg white, mazarine blue, underglaze blue, and peacock blue glazes were also innovations in ceramic coloring. The fact that a single work could have alternating linear patterns and framed decoration is a direct expression of the Mongol Yuan taste in design. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

1) Underglaze Blue: “Underglaze blue decoration in ceramics is achieved by painting a design with oxidized cobalt glaze pigment, then covering it with a transparent glaze, and then firing at high temperatures. This blue painted design against a white background that is protected by a transparent glaze is what is known as "underglaze blue". Blue-and-white ceramics appeared as early as the T'ang dynasty, but they did not flourish until the Yuan period. Both fine and opulent as well as painterly and sketchy designs in underglaze blue became an important trend in later Chinese ceramics. \=/

2) “Peacock-blue Glaze: The Ching-te-chen and Tz'u-chou kilns began to fire ceramics with peacock-blue glaze at the beginning of the Yuan dynasty. This attractive glaze is fired at low temperatures. However, since the glaze pigment was imported from Persia, it did not hold well on traditional Chinese ceramics, resulting in a tendency to flake off.” \=/

3) Huo-chou Ware: “The production of white ceramics flourished in Huo County, Shansi province, and angled-waist plates and stem cups are obvious indications of production in the Yuan dynasty. The body of such ceramics is exceptionally white, and slender separators were used to stack the ceramics when firing. Some vessels also have delicately protruding patterns and designs. The fine linear patterns are said to be the work of the gold lacquer master P'eng Chun-pao.” \=/

4) “Mazarine Blue and Gold Coloring: Mazarine blue glaze translates directly in Chinese as "sky-clearing blue". This type of glaze is achieved with oxidized cobalt pigments fired at high temperatures. It rose in the Yuan dynasty, and the hue was a gem-like indigo blue. The most treasured examples have blue glaze decorated with gold coloring. The cup and plate shown here still retains traces of the gold rims, which indicate the opulence of these ceramics at the time.” \=/

5) “Brown-splashed Celadons: Glaze pigment with a large proportion of iron painted on ceramics appeared as early as green wares of the Six Dynasties period. This technique appeared intermittently throughout the centuries, but it was not until the Yuan dynasty that it achieved widespread popularity in the Lung-ch'uan celadons and blue-and-white wares from Ching-te-chen. Indeed, the splashed brown glaze is quite eye-catching. \=/

6) “Egg-white Porcelain Glaze: The innovative white porcelain glaze fired at Ching-te-chen was slightly bluish in color, similar to that of a duck egg (hence the name "egg-white"). It was opaque and thick, similar to jade. Typical ceramic forms include wide plates and angled-waist bowls, and decoration was often impressed winding branches and flowers in a fine and regular manner. Sometimes the designs conceal the characters for "shu" and "fu", making these the highly prized "Shu-fu wares".” \=/

Examples of Yuan Ceramics

The world record price paid for an art work from Asia is $27.8 million paid in March 2005 for a 14th century Chinese porcelain vessel with blue designs painted on a white background. The vessel contains scenes of historical events in the 6th century B.C. and has a unique Persian-influenced shape. Only seven jars of this shape exist in the world. The buyer was Giuseppe Eskenazi., the renowned dealer of Chinese art, acting on behalf of a client. The previous record for porcelain was $5.83 million paid in September 2003 for a14th-century blue-and-white porcelain vessel called the pilgrims vessel.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Wine Jar with Lion-Head Handles, porcelain, underglaze painted: “Artistic ideas, materials, and objects traveled across Asia in the Mongol period to the distant poles of the empire and beyond. This Chinese wine jar was probably made specifically for export to the west, possibly to Iran. Similarly, its visual motifs were transmitted to the west, where they were employed on Ilkhanid tiles, bowls, and jars. The introduction and rise of blue-and-white porcelain in Yuan China is likely attributable to this fertile interaction: the Iranian cobalt ore was sent east to China, and highly sought after Chinese blue-and-white porcelains were exported west.The cloud-collar motif appears on the shoulder of the jar and within the cloud collar motifs are soaring phoenixes set against a floral ground that circles the body. This piece belongs to the The Cleveland Museum. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of Blue Vase with Flying Phoenix Decor, ceramic (height: 29.5 centimeters, base diameter: 9.2 centimeters): With a rim flaring outward, a slender neck, a globular body, and a ring base, the base of this vase is done with a cream underglaze tinged with blue. The neck and body are decorated with a pattern in blue-and-white of peonies, vines, and phoenixes. The body at the widest part has a band of curling forms, below which is a row of lotus petal designs. This is a typical pear-shaped vase of the Yuan dynasty but of exceptional quality and decoration, making it a masterpiece of blue-and-white ceramics from this period. This belongs to the Collection: Municipal Antique Store (T'ung-liao, Inner Mongolia). [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

Chun Ware

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “Chun ware porcelain is famous for the color of its glazes. The glaze colors used on the majority of Chun wares, such as vessels, incense burners, bowls, and plates in the National Palace Museum collection, are bluish-green, greenish-blue, and sky blue. Copper red coloring pigment was applied on some green or blue glaze bases in order to create a visual effect like the glow of the sunset. The richness of the glaze colors of objects like planters and pot stands was beyond imagination. Two different colors, hues, or tones on both the inside and the outside of the vessel occurred frequently. Ancient scholars thus referred to the glaze on Chun ware as "art by accident". Since the Ming dynasty, the literati have commented regularly on Chun glaze, as in Kao Lien's Tsun-sheng pa-chien (Eight Discouves on a Healthful Life Style) (1591) where he used terms such as cinnabar-red, shallot-green, and eggplant-purple to describe the brilliant glaze on Chun ware. The predominant colors of the Museum's Chun ware collection are green, blue, purple and red. The variety in levels of tone in the same hue and the mixture of the different colors in the wares is also an important aspect of this collection. The work "Inverted bell-shaped planter with sky-blue and rose-purple glaze" is a good example of the above technique where specks of light blue and rose red appear on the sky blue glaze base, while copper red forms a ribbon-like pattern on the rim of the ware. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The question as to whether or not Chun ware was made during the Northern Sung dynasty has always confused researchers in this field. The theory that Chun ware was indeed produced during the Northern Sung (960-1127) dynasty originated during the late Ming (ca. 16-17th century), when scholars identified five major wares — Ting, Ju, Kuan, Ko, and Chun. In publications such as the Nan-yao pi-chi (The Notebook of Nan Ware), T'ao-Shu (The Theory of Ceramic), and Ching-te-chen t'ao-lu (The Ceramic Record of Ching-te-chen), Chun was referred to as a product of the Northern Sung dynasty (960-1279). The need to re-evaluate this analysis was proposed in 1975, when there was new evidence unearthed from Yu County in Henan Province suggesting that Chun ware may have been made during another time period. The structure of the kilns, the casting mold, and unearthed items from this site have raised many yet unanswered questions. The confirmation of the chronology of Chun ware is still ambiguous and difficult to attain. Until convincing archaeological evidence has been excavated, Chun ware will not be classified as a product made during the Northern Sung dynasty. Unlike previous exhibitions of Chun ware, some of the displayed items in this exhibition have yet to be conclusively dated and will therefore not be labeled as a product of the Sung dynasty (960-1279). \=/

“The Chun ware collection of the National Palace Museum includes utilitarian wares, such as vessels, bowls, plates, and incense burners, as well as planters, pot stands and a tsun vase. The above works can be identified as pieces that were fired in the Chin (1115-1234) or Yuan (1271-1368) dynasty according to the observation of Chun ware excavated from ware cellars, kiln sites and dated tombs. Documents from the Ming (1368-1644) and Ch'ing (1644-1911) dynasties refer to Yu County as the origin of Chun ware production. The discovery of most of these cellars and kilns containing Chun ware in Henan Province supports this assertion. In order to deliver a more effective viewing experience for the audience, a map of cellar and kiln sites has been prepared. Shards of Chun ware that have been recovered in Lin-ju, Pao-feng, Ho-pi, Yeh-chu-kou, and Liu-chia-men in Henan Province have been put on display. Through observing the shards, and comparing the colors of the glazes, viewers will be able to distinguish the difference between the glaze colors from different places and thus appreciate the diversity and beauty of Chun ware. \=/

“Chun ware appears thick and milky in quality. After low temperature firing and multi-layer glazing, cracks sometimes occurred during the first few firing processes. These cracks were then covered with new layers, leaving a unique pattern known as the "pattern of a worm trail along the ground", which can be seen in the "Hibiscus-shaped planter with moon-white glaze" in this exhibition. The Chun ware displayed has a thick clay body. The layers of glaze on the edges of these types of works are thinner and are an earthy yellow in color. This is in contrast with the thick layers of colored glaze on the body. In order to showcase the dazzling colors of Chun ware, some of displayed items are partially enlarged and reproduced, so that the uniqueness of its beauty with ever changing colors can be clearly seen in detail. \=/

Examples of Yuan Dynasty Chun Ware

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of Bowl with Greenish-blue Glaze and Reddish-purple Splashes (height: 8.9 centimeters, rim width: 15 centimeters, foot width: 4.6 centimeters): This bowl has a contracted round rim, deep sides, concave center, and a short conical base on a slightly everted ring foot. The shape is similar to a "lotus bowl." Covered with a greenish-blue glaze, it appears creamy yellow along the rim. The body bears decorative splashes of reddish-purple glaze that evoke atmospheric colors against a bluish sky. The glaze is covered with a light crackle and extends down to the base, the underside of which reveals a clump of glaze. The other areas of the foot and underside are unglazed, exposing the brownish color of the body. The rim of the foot has been scraped unevenly, the inner edge being longer than the outer one. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of Ju-i Pillow with Azure Glaze and Purple Splashes (height: 13.4 centimeters, length: 28-30.8 centimeters, width: 19-19.7 centimeters): “This pillow is in the shape of a ju-i. With an irregular profile, the front is lower than the back, and it has a depression in the middle. On the back wall are two gourd-shaped holes facing towards the middle at an angle. Hollow inside, the body of this ceramic is quite heavy and thick, and it is covered with an azure glaze that runs down to the base. Since the glaze was quite viscous, it created an uneven thick border when it ran down to the bottom. The rim is brown, and the azure-glazed top is decorated with purplish-red splotch marks. The glaze is covered with a fine, dark crackle pattern. The bottom is unglazed, revealing the dark body, which was incised in 1776 with a poem by the Ch'ien-lung emperor along with two of his seals. The ju-i pillow appeared as early as the Sung dynasty (960-1279), with surviving examples ranging from tri-color to incised white ware. Compared to Sung ju-i pillows, Chun ware ones of the Yuan dynasty have outlines that are simpler and more distinct. The deliberate tilting and irregular surface makes the pillow even more narrow and straight. \=/

National Palace Museum, Taipei description of Brush Washer with Bluish-green Glaze, Chin to Yuan dynasty (12th-13th century) (height: 5.8 centimeters, rim width: 18.1 centimeters, base width: 9.7 centimeters): This dish has a contracted circular rim with a shallow, slightly rounded body. It has a flat bottom, no foot ring, and is covered with a bluish-green glaze that is evenly thin. The rim has a slight ridge in creamy yellow color. The glaze surface is uneven and pitted. The glaze, covering the entire vessel, is punctuated only on the bottom by five spur marks. The form, glaze color, and ridge of this vessel is similar to ones excavated from the Chun kiln site at Yu-chou, Henan. \=/

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021