SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ECONOMY

Early paper money The Songs ruled an empire rich in silk, jade and porcelain. They sent trading ships to India and Java and presided over a period of growth in trade and an expansion of the Chinese empire. Trade increased in the Indian Ocean partly as a response to the threat from Islamic intrusions into the area. Even so trade was not a respectable vocation and the emperor seized the property of merchants to create government monopolies.

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Farmers in Song China did not aim at self-sufficiency. They had found that producing for the market made possible a better life. Farmers sold their surpluses in nearby markets and bought charcoal, tea, oil, and wine. Some of the products on sale in the city depicted in the scroll would have come from nearby farms, but others came from far away. In many places, farmers specialized in commercial crops, such as sugar, oranges, cotton, silk, and tea. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

Merchants in the cities became progressively more specialized and organized. They set up partnerships and joint stock companies, with a separation between owners (shareholders) and managers. In large cities merchants were organized into guilds according to the type of product they sold. Guilds arranged sales from wholesalers to shop owners and periodically set prices. When the government wanted to requisition supplies or assess taxes, it dealt with the guild heads.

“The many rivers and streams of the region facilitated shipping, which reduced the cost of transportation and, thus, made regional specialization economically more feasible. During the Song period, the Yangzi River regions became the economic center of China.

The role of merchants in the Song (and throughout Chinese history) belies the conventional stereotype of China suppressing merchant activity. Robert Hymes of Columbia University wrote: “The older Tang market system, which had strictly confined trade to cities and within cities to specific sites and hours, utterly broke down as urban commerce spread throughout cities and into extramural mercantile quarters. Over long distances, large cities and whole regions of dense population came to depend on ship-borne bulk trade in staple goods, especially rice. Over shorter distances, trade penetrated the countryside, drawing farmers into new periodic market centers and rapidly proliferating market towns.” [Source: Robert Hymes, from “Song China, 960-1279,” in Asia in Western and World History, edited by Ainslie T. Embree and Carol Gluck (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1997).

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: TANG, SONG AND YUAN DYNASTIES factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (A.D.960-1279) factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY (960-1279) ADVANCES factsanddetails.com; GOVERNMENT, BUREAUCRACY, SCHOLAR-OFFICIALS AND EXAMS DURING THE SONG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; SU SHI (SU DONGPO)—THE QUINTESSENTIAL SCHOLAR-OFFICIAL-POET factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; WANG ANSHI, HIS REFORMS AND HIS BATTLE WITH SIMA GUANG factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY LIFE factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CULTURE: TEA-HOUSE THEATER, POETRY AND CHEAP BOOKS factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY ART, PAINTING AND CALLIGRAPHY SONG DYNASTY factsanddetails.com; LANDSCAPE, ANIMAL, RELIGIOUS AND FIGURE PAINTING factsanddetails.com; SONG DYNASTY CERAMICS factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Primary Sources with DBQs, afe.easia.columbia.edu ; Wikipedia Wikipedia ; San.beck.org san.beck.org ; Chinese Text Project ctext.org Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization depts.washington.edu

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: The Genius of China: 3,000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention by Robert K.G. Temple Amazon.com; Ancient China's Inventions, Technology and Engineering - Ancient History Book for Kids by Professor Beaver Amazon.com; Science and Civilisation in China. Volume 1: Introductory Orientations by Joseph Needham Amazon.com; The Shorter Science and Civilisation in China: an Abridgement of Joseph Needham's Original Text By Colin a Ronan Amazon.com; The Four Great Inventions of Ancient China: Their Origin, Development, Spread and Influence in the World by Jixing Pan Amazon.com “The Reunification of China” by Peter Lorge Amazon.com; “The Making of Song Dynasty History: Sources and Narratives, 960–1279 CE” by Charles Hartman Amazon.com; “Ten States, Five Dynasties, One Great Emperor: How Emperor Taizu Unified China in the Song Dynasty” by Hung Hing Ming Amazon.com; “The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5 Part One: The Five Dynasties and Sung China And Its Precursors, 907-1279 AD” by Denis Twitchett and Paul Jakov Smith Amazon.com; “Cambridge History of China, Vol. 5 Part 2 The Five Dynasties and Sung China, 960-1279 AD” by John W. Chaffee and Denis Twitchett Amazon.com; “Chinese Urbanism: Urban Form and Life in the Tang-song Dynasties” by Jing Xie Amazon.com

Innovation and the Song Era Economy

Song river ship

According to the “Middle Ages Reference Library”: “An explosion in scientific knowledge accompanied an economic boom. On the high seas, the development of the magnetic compass made navigation at sea much easier, and along with improvements in shipbuilding, enabled the Song to send ships called junks on merchant voyages. The larger Song junks could hold up to six hundred sailors, along with cargo. [Source: Middle Ages Reference Library, Gale Group, Inc., 2001]

“Tea and cotton emerged as major exports, and a newly developed rice strain, along with advanced agricultural techniques, enhanced the yield from China's farming lands. China also sold a variety of manufactured goods, including books and porcelain, while steel production and mining grew dramatically.

“In this vibrant economy, banks and paper money—one of Song China's most notable contributions—made their appearance, and the development of movable-type printing aided the spread of information. Instead of carving out a whole block of wood, a printer assembled pre-cast pieces of clay type (later they used wood), each of which stood for a character in the Chinese language. Ultimately, however, the peculiarities of Chinese would encourage the use of block printing over movable type. It is easy enough to store and use pieces of type when a language has a twenty-six-letter alphabet, as English does; but Chinese has some 30,000 characters or symbols, meaning that printing by movable type was extremely slow.

Development in the Song Era Economy

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “Trade, including overseas trade, developed greatly from now on. Soon we find in the coastal ports a special office which handled custom and registration affairs, supplied interpreters for foreigners, received them officially and gave good-bye dinners when they left. Down to the thirteenth century, most of this overseas trade was still in the hands of foreigners, mainly Indians. Entrepreneurs hired ships, if they were not ship-owners, hired trained merchants who in turn hired sailors mainly from the South-East Asian countries, and sold their own merchandise as well as took goods on commission. Wealthy Chinese gentry families invested money in such foreign enterprises and in some cases even gave their daughters in marriage to foreigners in order to profit from this business. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“We also see an emergence of industry from the eleventh century on. We find men who were running almost monopolistic enterprises, such as preparing charcoal for iron production and producing iron and steel at the same time; some of these men had several factories, operating under hired and qualified managers with more than 500 labourers. We find beginnings of a labour legislation and the first strikes (A.D. 782 the first strike of merchants in the capital; 1601 first strike of textile workers).

“Some of these labourers were so-called "vagrants", farmers who had secretly left their land or their landlord's land for various reasons, and had shifted to other regions where they did not register and thus did not pay taxes. Entrepreneurs liked to hire them for industries outside the towns where supervision by the government was not so strong; naturally, these "vagrants" were completely at the mercy of their employers.

Song Dynasty Trade and Commerce

The Song dynasty is notable for the development of cities not only for administrative purposes but also as centers of trade, industry, and maritime commerce. The landed scholar-officials, sometimes collectively referred to as the gentry, lived in the provincial centers alongside the shopkeepers, artisans, and merchants. A new group of wealthy commoners — the mercantile class — arose as printing and education spread, private trade grew, and a market economy began to link the coastal provinces and the interior. Landholding and government employment were no longer the only means of gaining wealth and prestige.

The Songs ruled an empire rich in silk, jade and porcelain. They sent trading ships to India and Java and presided over a period of growth in trade and an expansion of the Chinese empire. Trade increased in the Indian Ocean partly as a response to the threat from Islamic intrusions into the area. Even so trade was not a respectable vocation and the emperor seized the property of merchants to create government monopolies.

Frances Wood, curator of the Chinese collection at the British Library told the BBC: "Under the previous dynasties, the cities were fairly rigidly controlled. Markets were held on fixed days, on fixed points and so on. "By the Song dynasty, you begin to get ordinary city life as we know it. Cities are much freer, so commerce is much freer." [Source:Carrie Gracie, BBC News, October 17, 2012 \=]

Peter Bol of Harvard University told the BBC the Chinese economy was far more commercialised than it had ever been before: "The money supply has increased 30-fold. The merchant networks have spread. Villages are moving away from self-sufficiency and getting connected to a cash economy. The government no longer controls the economic hierarchy, which is largely in private hands... it's a far richer world than ever before." \=\

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “But all this created problems. As large land-owning estates grew, so did the number of people who were unwilling to pay their taxes - and the more rich people evaded tax, the more the burden fell on the poor. There was also problem with the neighbours. The Song emperors often found themselves at war on their northern borders. Jin and Mongol invaders were annexing Chinese land, so lots of money had to be spent on defence, and inflation took hold. The dynasty was plunged into crisis. \=\

Trade in South China in the 10th Century

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: ““The prosperity of the small states of South China was largely due to the growth of trade, especially the tea trade. The habit of drinking tea seems to have been an ancient Tibetan custom, which spread to south-eastern China in the third century A.D. Since then there had been two main centres of production, Sichuan and south-eastern China. Until the eleventh century Sichuan had remained the leading producer, and tea had been drunk in the Tibetan fashion, mixed with flour, salt, and ginger. It then began to be drunk without admixture. In the Tang epoch tea drinking spread all over China, and there sprang up a class of wholesalers who bought the tea from the peasants, accumulated stocks, and distributed them. From 783 date the first attempts of the state to monopolize the tea trade and to make it a source of revenue; but it failed in an attempt to make the cultivation a state monopoly. A tea commissariat was accordingly set up to buy the tea from the producers and supply it to traders in possession of a state licence. There naturally developed then a pernicious collaboration between state officials and the wholesalers. The latter soon eliminated the small traders, so that they themselves secured all the profit; official support was secured by bribery. The state and the wholesalers alike were keenly interested in the prevention of tea smuggling, which was strictly prohibited. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“The position was much the same with regard to salt. We have here for the first time the association of officials with wholesalers or even with a monopoly trade. This was of the utmost importance in all later times. Monopoly progressed most rapidly in Sichuan, where there had always been a numerous commercial community. In the period of political fragmentation Sichuan, as the principal tea-producing region and at the same time an important producer of salt, was much better off than any other part of China. Salt in Sichuan was largely produced by, technically, very interesting salt wells which existed there since c. the first century B.C. The importance of salt will be understood if we remember that a grown-up person in China uses an average of twelve pounds of salt per year. The salt tax was the top budget item around A.D. 900.

“South-eastern China was also the chief centre of porcelain production, although china clay is found also in North China. The use of porcelain spread more and more widely. The first translucent porcelain made its appearance, and porcelain became an important article of commerce both within the country and for export. Already the Muslim rulers of Baghdad around 800 used imported Chinese porcelain, and by the end of the fourteenth century porcelain was known in Eastern Africa. Exports to South-East Asia and Indonesia, and also to Japan gained more and more importance in later centuries. Manufacture of high quality porcelain calls for considerable amounts of capital investment and working capital; small manufacturers produce too many second-rate pieces; thus we have here the first beginnings of an industry that developed industrial towns such as Ching-tê, in which the majority of the population were workers and merchants, with some 10,000 families alone producing porcelain. Yet, for many centuries to come, the state controlled the production and even the design of porcelain and appropriated most of the production for use at court or as gifts.

Expansion of Commerce under the Northern Song

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The Song founders established their court at a city that had not previously served as a dynastic capital. The city of Kaifeng lay in China’s midlands, just south of the Yellow River. The decision to take Kaifeng as a base rather than the Tang capital of Chang’an reflected a change in the circumstances and goals of the dynasty. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University/+/ ]

“Chang’an had been considered ideal by the Tang because of its status as the terminus of the “Silk Route,” the channel of foreign trade through Central Asia, and because of its strong military defensibility. The new Song government was far less interested in these advantages. Kaifeng was better suited to Song goals because it had become a terminus of the Grand Canal – its connection by canal with the southern urban center of Hangzhou made it a focus of internal commerce. The Song aspired to focus on building the wealth and social cohesion of the heartland regions of China, and a capital located at Kaifeng was ideal for these purposes. /+/

“For almost 1000 years, since the disastrous Yellow River floods of the early first century, the population of China had been gradually shifting from the fertile but dry lands of the North towards the South, a region characterized by a warm, moist climate and by a multitude of naturally navigable waterways. This shift accelerated during the peaceful years of the early Song, as farmers sought to open new lands in the South on which to grow rice, which was becoming increasingly popular throughout China, and also to produce other crops that Northerners would find exotic and attractive, such as tea. /+/

“In the South, crops could be grown year round, and Major North-South canals fostered a lively inter-regional trade that heated China’s economy to levels unseen before in the world. The South became particularly wealthy. Farming populations began to grow at spectacular rates, and enormously wealthy merchant families began to purchase large tracts of land, rent them out to peasant tenants, collect high rents, and use their wealth to gather together in increasingly large urban centers, where the upper classes lived in remarkable luxury. The growth of some of the largest Chinese cities, such as Guangzhou (Canton) and Nanjing, dates from this period.” /+/

Song Dynasty Shops and Commerce

Patricia Buckley Ebrey of the University of Washington wrote: “Along the River During the Qingming Festival” by Zhang Zeduan (1085–1145) provides a wealth of detail on the varieties of commercial activity of its day. Kaifeng, like other large cities, had developed into a vast trading center, in addition to being the political seat of the country. This economic expansion was aided by an increasingly sophisticated transportation network and the establishment of trade guilds that specialized in movement of commodities over land and through the Grand Canal by large-scale merchants and itinerant peddlers. The more easily goods were moved throughout the country, the more local specialization in production was possible, and overall production as a result increased dramatically. [Source: Patricia Buckley Ebrey, University of Washington, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=]

“A close-up view of vendors on the rainbow bridge, shows a different type of commercial setting. The gentleman seated at the center of the table is a prognosticator by trade; his signs advertise his fortune telling abilities. The scene of vendors' tables located just off a busy street corner near the inner city wall is framed by the following signs: across the front, The Family of Assistant Zhao; next to the women, facing front, Care for the Five Wounds and Seven Injuries and Deficiencies of Speech; perpendicular to the shop front, facing right, Regulation of Alcohol-related Illnesses and Prevention of Injury, Genuine Prescriptions of the Collected Fragrances Remedy. The signs behind the fence identify the permanent shops behind these temporary vendors; the larger sign to the left (behind the seated man) is for a wine shop of "Premium Quality", and the other narrow sign to the right (partially obscured by a column) indicates a silk merchant's shop.” /=\

Commerce During the Southern Song

China's per capita income adjusted for inflation was higher at the end of the Song Dynasty in the 1270s than it was under Mao in the 1950s. Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “The influx of people into South China was actually an economic boon. While lands in the fertile North China Plain had been the heartland of Chinese agricultural production for millennia, there was a great deal of land in the South that had never been cleared for cultivation, and the settlers who fled from the invasion began to open these lands and bring them into production. Southern agriculture was based on rice, and rice had become a dietary item in great demand in the North. In the eleventh century, new strains of rice that allowed farmers to raise two crops in a season had been introduced, and now these contributed to an outburst of productivity in the expanding agricultural lands of the south. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

“The Song, when based at Kaifeng, had made sure that the Grand Canal was in good repair, and now, although North and South were under different jurisdictions, the canal became the central conduit for an active inter.regional trade, including not only staples from the South such as rice and tea, but a wide variety of goods that climate or traditional cultural made scarce in one region or the other. As trade grew in volume, new devices were developed to support it. Coinage had been dramatically increased during the early Song, so that cash payments could facilitate trade. Now, with commerce reaching new levels, paper currency was developed, and new banking institutions were invented to allow for investment, credit, and cash savings. But it is questionable the truly dramatic leap in agricultural output and commercial activity of the Song era would have occurred without the migrations that followed the Jurchen invasions, forcing exploitation of southern resources that had lain untouched before. The economic growth in the South resulted in rapid urbanization. During the Southern Song period, a number of southern cities are estimated to have housed populations close to one million – the largest cities in the world at the time. These concentrations further spurred the development of diverse markets for craft goods, such as ceramics, of which the Song craftsmen became unsurpassed masters (which is books. In response, Song artisans invented movable type and launched a printing industry unmatched in the world. /+/

Maritime Trade During the Song Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Trade between the Song dynasty and its northern neighbors was stimulated by the payments Song made to them. The Song set up supervised markets along the border to encourage this trade. Chinese goods that flowed north in large quantities included tea, silk, copper coins (widely used as a currency outside of China), paper and printed books, porcelain, lacquerware, jewelry, rice and other grains, ginger and other spices. The return flow included some of the silver that had originated with the Song and the horses that Song desperately needed for its armies, but also other animals such as camel and sheep, as well as goods that had traveled across the Silk Road, including fine Indian and Persian cotton cloth, precious gems, incense, and perfumes. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“There was also vigorous sea trade with Korea, Japan, and lands to the south and southwest. From great coastal cities such as Quanzhou boats carrying Chinese goods plied the oceans from Japan to east Africa. (The major port of Quanzhou that dominated trade in the Song dynasty is not to be confused with Guangzhou. Guangzhou, located further south on the Chinese coast, did not become an important port until the Qing dynasty, when it was known to European traders as “Canton.”

“During Song times maritime trade for the first time exceeded overland foreign trade. The Song government sent missions to Southeast Asian countries to encourage their traders to come to China. Chinese ships were seen all throughout the Indian Ocean and began to displace Indian and Arab merchants in the South Seas. Shards of Song Chinese porcelain have been found as far away as eastern Africa."

Song junk

“Chinese ships were larger than the ships of most of their competitors, such as the Indians or Arabs, and in many ways were technologically quite advanced. In 1225 the superintendent of customs at Quanzhou, named Zhao Rukua (Zhao Rugua or Chao Ju-kua, 1170-1231), wrote an account of the countries with which Chinese merchants traded and the goods they offered for sale. Zhao's book, Zhufan Zhi (commonly translated as "Description of the Barbarians"), includes sketches of major trading cities from Srivijaya (modern Indonesia) to Malabar, Cairo, and Baghdad. Pearls were said to come from the Persian Gulf, ivory from Aden, myrrh from Somalia, pepper from Java and Sumatra, cotton from the various kingdoms of India, and so on.

“Much money could be made from the sea trade, but there were also great risks, so investors usually divided their investment among many ships, and each ship had many investors behind it. In 1973 a Song-era ship was excavated off the south China coast. It had been shipwrecked in 1277. Seventy-eight feet long and 29 feet wide, the ship had twelve bulkheads and still held the evidence of some of the luxury objects that these Song merchants were importing: more than 5,000 pounds of fragrant wood from Southeast Asia, pepper, betel nut, cowries, tortoiseshell, cinnabar, and ambergris from Somalia.”

On the importance of maritime trade, Lynda Noreen Shaffer wrote: “The new importance of the south [of China] also encouraged China to face south toward the Southern Ocean (the South China Sea, the Indian Ocean, and parts between) for the first time, and Chinese maritime capabilities developed steadily from the twelfth century to the fifteenth.” [Source: Lynda Noreen Shaffer, In “A Concrete Panoply of Intercultural Exchange: Asia in World History,” in Asia in Western and World History, edited by Ainslie T. Embree and Carol Gluck (Armonk, N.Y.: M.E. Sharpe, 1997), 840]

Southern Song (1127-1279) Maritime Trade

According to the National Palace Museum, Taipei: “In the Southern Song period, communication in art and culture with foreign lands occurred not only through exchange among people and goods with the Jin dynasty to the north, but also in the development of trade with areas to the southeast and southwest. Of particular importance was the expansion of foreign trade via sea routes. With the rise of large harbors dealing in foreign trade at Guangzhou, Quanzhou, Lin'an, and Mingzhou (Ningbo, Zhejiang), the area of trade expanded to the South China Sea and west to as far as Persia, the Mediterranean Sea, and East Africa. The development of Chan (Zen) Buddhist painting and calligraphy was also an important link for the spread of Song culture. [Source: National Palace Museum, Taipei \=/ ]

“The Southern Song was a time of commerce, with paper money in wide circulation as well as gold, silver leaves or ingots being common currencies, whereas its copper coins went beyond the borders and became the key medium of exchange in many surrounding nations. Through the frontier trading posts, the jewelry and porcelain of the Jin State arrived in the Jiangnan and vast quantities of tea, silk, and herbs of the Southern Song shipped north. Jin and Song as a result shared kindred spirit artistically and literarily. Sea routes also took Chinese merchandise far and wide to many other Asian countries; foreign merchants reaching the shores of China in return brought enriching cultural messages. At the same time, the Taiwan Island and its nearby islets saw the coming and going of the Southern Song traders; their footprints are still here today for us to reminisce about a splendid past.” \=/

Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: ““Economic activity and the rising demand for goods was a major spur to scientific and technological creativity, and the foremost historian of the history of science in China has maintained that virtually every core invention of Chinese science traces its origins or a significant innovation to the Song period. For example, the rising output of goods in the South created incentives for the development of maritime trade, so that Chinese goods could reach new markets abroad. The old Silk Route was no longer available to the Song, and, in any event, climate changes had made it much less hospitable to caravan travel than had been the case during the Tang. So for the first time in Chinese history, the merchant class turned towards the sea as a potential commercial highway. Responding to this need, craftsmen applied known technology to create the maritime compass, which allowed ships to navigate as far as the Red Sea, to trade with Middle Eastern markets. Shipbuilding became a major industry, and a host of inventions led to the construction of technologically advanced ships, adaptable to both commercial and military uses.” [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ]

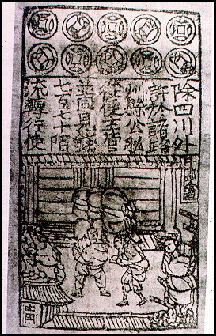

Paper Money Introduced During the Song Dynasty

During the Song dynasty (960—1279 AD) Chinese paper money was introduced and became widely circulated through the Mongol Empire during the Yuan Dynasty. These note remained in use through the Ming and Qing Dynasties. The first paper note, called “Jiao Zi” for trade, was issued in Sichuan Province, where widely-used. Early Song iron coins were light in value and heavy to carry. Merchants issued the Jiao Zi not to facilitate trade. [Source: Shanghai Museum]

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “Helping to grease the wheels of trade during the Song was the world’s first paper money. For centuries, the basic unit of currency in China was the bronze or copper coin with a hole in the center for stringing. Large transactions were calculated in terms of strings of coins, but given their weight these were cumbersome to carry long distances. As trade increased, demand for money grew enormously, so the government minted more and more coins. By 1085 the output of coins had increased tenfold since Tang times to more than 6 billion coins a year. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“The use of paper currency was initiated by merchants. To avoid having to carry thousands of strings of coins long distances, merchants in late Tang times (c. 900 CE) started trading receipts from deposit shops where they had left money or goods. The early Song authorities awarded a small set of shops a monopoly on the issuing of these certificates of deposit, and in the 1120s the government took over the system, producing the world’s first government-issued paper money. The earliest example of paper currency that survives today is the great Ming circulating treasure note, from 1375.”

Yuan dynasty banknote printing plate

Marco Polo described the use of paper currency during the Mongol Yuan dynasty: With these pieces of paper, made as I have described, he [Kublai Khan] causes all payments on his own account to be made; and he makes them to pass current universally over all his kingdoms and provinces and territories, and whithersoever his power and sovereignty extends. And nobody, however important he may think himself, dares to refuse them on pain of death. And indeed everybody takes them readily, for wheresoever a person may go throughout the Great Kaan’s dominions he shall find these pieces of paper current, and shall be able to transact all sales and purchases of goods by means of them just as well as if they were coins of pure gold. And all the while they are so light that ten bezants’ worth does not weigh one golden bezant. [Source: Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa, “Book Second, Part I, Chapter XXIV: How the Great Kaan Causeth the Bark of Trees, Made into Something Like Paper, to Pass for Money over All His Country,” in The Book of Ser Marco Polo: The Venetian Concerning Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, translated and edited by Colonel Sir Henry Yule, Volume 1 (London: John Murray, 1903). This book is in the public domain and can be read online at Project Gutenberg. Chapter XXIV begins on page 587 of this online text /]

“Furthermore all merchants arriving from India or other countries, and bringing with them gold or silver or gems and pearls, are prohibited from selling to any one but the Emperor. He has twelve experts chosen for this business, men of shrewdness and experience in such affairs; these appraise the articles, and the Emperor then pays a liberal price for them in those pieces of paper. The merchants accept his price readily, for in the first place they would not get so good a one from anybody else, and secondly they are paid without any delay. And with this paper-money they can buy what they like anywhere over the Empire, whilst it is also vastly lighter to carry about on their journeys. And it is a truth that the merchants will several times in the year bring wares to the amount of 400,000 bezants, and the Grand Sire pays for all in that paper. So he buys such a quantity of those precious things every year that his treasure is endless, whilst all the time the money he pays away costs him nothing at all. Moreover, several times in the year proclamation is made through the city that anyone who may have gold or silver or gems or pearls, by taking them to the Mint shall get a handsome price for them. And the owners are glad to do this, because they would find no other purchaser give so large a price. Thus the quantity they bring in is marvellous, though these who do not choose to do so may let it alone. Still, in this way, nearly all the valuables in the country come into the Kaan’s possession.” /

Impact of Paper Money During the Song Dynasty

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: Another important innovation, that began in North China, was the introduction of prototypes of paper money. The Chinese copper "cash" was difficult or expensive to transport, simply because of its weight. It thus presented great obstacles to trade. Occasionally a region with an adverse balance of trade would lose all its copper money, with the result of a local deflation. From time to time, iron money was introduced in such deficit areas; it had for the first time been used in Sichuan in the first century B.C., and was there extensively used in the tenth century when after the conquest of the local state all copper was taken to the east by the conquerors. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

So long as there was an orderly administration, the government could send it money, though at considerable cost; but if the administration was not functioning well, the deflation continued. For this reason some provinces prohibited the export of copper money from their territory at the end of the eighth century. As the provinces were in the hands of military governors, the central government could do next to nothing to prevent this. On the other hand, the prohibition automatically made an end of all external trade. The merchants accordingly began to prepare deposit certificates, and in this way to set up a sort of transfer system. Soon these deposit certificates entered into circulation as a sort of medium of payment at first again in Sichuan, and gradually this led to a banking system and the linking of wholesale trade with it. This made possible a much greater volume of trade. Towards the end of the Tang period the government began to issue deposit certificates of its own: the merchant deposited his copper money with a government agency, receiving in exchange a certificate which he could put into circulation like money. Meanwhile the government could put out the deposited money at interest, or throw it into general circulation. The government's deposit certificates were now printed. They were the predecessors of the paper money used from the time of the Song.

Development of a Money Economy During the Song Dynasty

Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: “Since c. 780 the economy can again be called a money economy; more and more taxes were imposed in form of money instead of in kind. This pressure forced farmers out of the land and into the cities in order to earn there the cash they needed for their tax payments. These men provided the labour force for industries, and this in turn led to the strong growth of the cities, especially in Central China where trade and industries developed most. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“Wealthy people not only invested in industrial enterprises, but also began to make heavy investments in agriculture in the vicinity of cities in order to increase production and thus income. We find men who drained lakes in order to create fields below the water level for easy irrigation; others made floating fields on lakes and avoided land tax payments; still others combined pig and fish breeding in one operation.

“The introduction of money economy and money taxes led to a need for more coinage. As metal was scarce and minting very expensive, iron coins were introduced, silver became more and more common as means of exchange, and paper money was issued. As the relative value of these moneys changed with supply and demand, speculation became a flourishing business which led to further enrichment of people in business. Even the government became more money-minded: costs of operations and even of wars were carefully calculated in order to achieve savings; financial specialists were appointed by the government, just as clans appointed such men for the efficient administration of their clan properties. “Yet no real capitalism or industrialism developed until towards the end of this epoch, although at the end of the twelfth century almost all conditions for such a development seemed to be given.

Inflation During the Song Dynasty

The Song government was unable to meet the whole costs of the army and its administration out of taxation revenue. Wolfram Eberhard wrote in “A History of China”: The attempt was made to cover the expenditure by coining fresh money. In connection with the increase in commercial capital described above, and the consequent beginning of an industry, China's metal production had greatly increased. In 1050 thirteen times as much silver, eight times as much copper, and fourteen times as much iron was produced as in 800. Thus the circulation of the copper currency was increased. The cost of minting, however, amounted in China to about 75 per cent and often over 100 per cent of the value of the money coined. In addition to this, the metal was produced in the south, while the capital was in the north. The coin had therefore to be carried a long distance to reach the capital and to be sent on to the soldiers in the north. [Source: “A History of China” by Wolfram Eberhard, 1951, University of California, Berkeley]

“To meet the increasing expenditure, an unexampled quantity of new money was put into circulation. The state budget increased from 22,200,000 in A.D. 1000 to 150,800,000 in 1021. The Khitan state coined a great deal of silver, and some of the tribute was paid to it in silver. The greatly increased production of silver led to its being put into circulation in China itself. And this provided a new field of speculation, through the variations in the rates for silver and for copper. Speculation was also possible with the deposit certificates, which were issued in quantities by the state from the beginning of the eleventh century, and to which the first true paper money was soon added. The paper money and the certificates were redeemable at a definite date, but at a reduction of at least 3 per cent of their value; this, too, yielded a certain revenue to the state.

“The inflation that resulted from all these measures brought profit to the big merchants in spite of the fact that they had to supply directly or indirectly all non-agricultural taxes (in 1160 some 40,000,000 strings annually), especially the salt tax (50 per cent), wine tax (36 per cent), tea tax (7 per cent) and customs (7 per cent). Although the official economic thinking remained Confucian, i.e. anti-business and pro-agrarian, we find in this time insight in price laws, for instance, that peace times and/or decrease of population induce deflation. The government had always attempted to manipulate the prices by interference. Already in much earlier times, again and again, attempts had been made to lower the prices by the so-called "ever-normal granaries" of the government which threw grain on the market when prices were too high and bought grain when prices were low. But now, in addition to such measures, we also find others which exhibit a deeper insight: in a period of starvation, the scholar and official Fan Chung-yen instead of officially reducing grain prices, raised the prices in his district considerably. Although the population got angry, merchants started to import large amounts of grain; as soon as this happened, Fan (himself a big landowner) reduced the price again. Similar results were achieved by others by just stimulating merchants to import grain into deficit areas.

Iron, Steel and Coal During the Song Dynasty

Yuan dynasty smelting

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “ During Song times, heavy industry — especially the iron industry — grew astoundingly. Iron production reached around 125,000 tons per year in 1078 CE, a sixfold increase over the output in 800 CE. Iron and steel were put to many uses, ranging from nails and tools to the chains for suspension bridges and Buddhist statues. The army was a large consumer: steel tips increased the effectiveness of Song arrows; mass-production methods were used to make iron armor in small, medium, and large sizes; high-quality steel for swords was made through high-temperature metallurgy. Huge bellows, often driven by waterwheels, were used to superheat the molten ore. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

At first charcoal was used in the production process, leading to deforestation of large parts of north China. By the end of the 11th century, however, coal had largely taken the place of charcoal. Marco Polo wrote about coal: “It is a fact that all over the country of Cathay there is a kind of black stones existing in beds in the mountains, which they dig out and burn like firewood. If you supply the fire with them at night, and see that they are well kindled, you will find them still alight in the morning; and they make such capital fuel that no other is used throughout the country. [Source: Marco Polo and Rustichello of Pisa, “Book Second, Part I, Chapter XXX: Concerning the Black Stones That Are Dug in Cathay, and Are Burnt for Fuel,” in The Book of Ser Marco Polo: The Venetian Concerning Kingdoms and Marvels of the East, translated and edited by Colonel Sir Henry Yule, Volume 1 (London: John Murray, 1903). This book is in the public domain and can be read online at Project Gutenberg. Chapter XXX begins on page 603 of this online text /]

“It is true that they have plenty of firewood, too. But the population is so enormous and there are so many bath-houses and baths constantly being heated, that it would be impossible to supply enough firewood, since there is no one who does not visit a bath-house at least 3 times a week and take a bath - in winter every day, if he can manage it. Every man of rank or means has his own bathroom in his house....so these stones, being very plentiful and very cheap, effect a great saving of wood." /

Textiles, Silk and Ceramic During the Song Dynasty

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The common people mostly wore clothes made of plant fibers such as hemp and ramie, and, at the end of the period, cotton — but the most highly prized fabric at home and abroad was silk. The feeding of silkworms (which devoured vast quantities of mulberry leaves), the cleaning of their trays, the unraveling of the cocoons, the reeling and spinning of the silk filaments — all this was women’s work, as was the weaving of plain cloth on simple home looms. Professional weavers, mostly men working in government or private workshops, operated complex looms to weave the fancy damasks, brocades, and gauzes favored by the elite. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University, Consultants Patricia Ebrey and Conrad Schirokauer afe.easia.columbia.edu/song ]

“In Song times China was a ceramics-exporting country. Song kilns produced many kinds of cups, bowls, and plates, as well as boxes, ink slabs, and pillows (headrests). Techniques of decoration ranged from painting and carving to stamping and molding. Some kilns could produce as many as 20,000 objects a day for sale at home and abroad. Shards of Song porcelain have been found all over Asia.

Seeds of an Industrial Revolution in China, 1000-1200

Chinese steam machine

Mark Elvin wrote in the Far Eastern Economic Review, “Early in the 11th century, Chinese government arsenals manufactured more than 16 million identical iron arrowheads a year. In other words, mass production. Rather later, in the 13th century, machines in northern China powered by belt transmissions off a waterwheel twisted a rough rope of hemp fibers into a finer yarn. The machine used 32 spinning heads rotating simultaneously in a technique that probably resembled modern ring-spinning. A similar device was used for doubling filaments of silk. In other words, mechanized production, in the sense that the actions of the human hand were replicated by units of wood and metal, and an array of these identical units was then set into motion by inanimate power. [Source: "The X Factor," by Mark Elvin, Far Eastern Economic Review, 162/23, June 10, 1999 ]

“Common sense thus suggests that the Chinese economy, early in the millennium just coming to a close, had already developed the two key elements of what we think of as the Industrial Revolution: mass production and mechanization... Much later, from the middle of the 19th century on, China had to import, then service, adapt, and even at times improve, mechanical engineering from the West. This was done with considerable flair, particularly by Chinese firms in Shanghai, a city which during treaty-port days turned into a nonstop international exhibition of machine-building. So Chinese technical capability can hardly be said to have withered in the intervening centuries... Why did the first industrial revolution not take place in China, as it seems it should have?’

Image Sources: Paper Money, Brooklyn College; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Robert Eno, Indiana University /+/ ; Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; National Palace Museum, Taipei; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated August 2021