TRANSPORTATION IN BEIJING

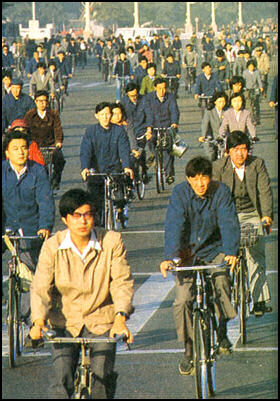

Bicycle riders in the old days

Most people get around on foot, by taxi or use the good but sometimes crowded subway system. The buses are cheap but are crowded and difficult to sort out. Beijing has excellent new airports but the roads getting to them can be congested. Rickshaws are still seen in the hutongs and some the tourist areas. Push carts are common. Occasionally you see horse carts. Web Sites: Beijing Page Maps of Beijing: chinamaps.org

Beijing is a major transportation hub. Six Ring Roads serve the city. The 1st Ring Road is not an actual road, but refers to the original wall around the "Old City." Eleven National Highways radiate out from city. All are major truck routes. Airlines connect Beijing to more than 110 cities at home and abroad while the city boasts a fine railroad and highway system for local travelers.

The Bohai Economic Rim, or "Rim", is a mega-metropolitan area — like the Tri-State area of New York or even the Washington D.C.-to- Boston corridor — that includes major cities in region near Bohai Sea. A network of expressways and high- speed rail lines links Beijing, Tianjin, Dalian, Shenyang, Jinan, Qingdao, Weihai and other major cities in the region. Cities in the Rim are major manufacturing, science and technology centers. Existing transport routes in the "Rim" provide rapid transport options. Heavy truck traffic is common on roads linking cities.

On public transport in Beijing, Julie Makinen wrote in the Los Angeles Times: Getting around China's congested capital requires a certain calculus: In choosing a means of transportation, you must weigh factors like rush-hour traffic, precipitation and how long you can stand being pressed up against a stranger's armpit....Taxis in Beijing are cheap for a world capital, but demand is so brisk that hailing one can be tough even on a blue-sky day. The subway? A bargain at 32 cents per trip, but the station was too far to walk. The bus? Even cheaper, but I didn't know which line to use. A pricey, unmarked, unauthorized "black cab"? None in sight. I saw but one option: a bicycle rickshaw. [Source: Julie Makinen, Los Angeles Times, October 7, 2012]

Geography and Orientation in Beijing

Greater Beijing is a municipality that covers an area about the size of Belgium and is divided in Beijing proper, its suburbs and nine counties. With the exception of the Great Wall of China, the Ming Tombs and the Summer Palace, most places of interest to tourists are located in central Beijing within walking distance of or a short taxi ride from the Forbidden Palace and Tiananmen Square. Most historic sites and museums are located inside the 2nd Ring Road. The City's older residential areas consist of hutongs, neighborhoods linked together by many narrow, winding streets. Most hutongs are located inside the 2nd Ring Road. The Shichahai area has many hutongs. The hutongs have many courtyard residences, known as siheyuan. Roads are safer for cycling due to less traffic. Be alert for older pedestrians and children.Tourists often tour hutongs by pedicabs.

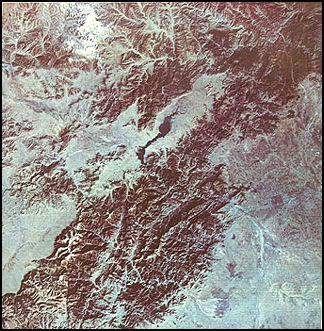

Beijing sprawls over a huge area of 16,410.5 square kilometers. It is situated on the northern end of the North China Plain. To the west and north are hills. To the south and east is flat, fertile farmlands. The Metropolitan area includes 16 districts and two counties. About 38 percent of the city is fairly flat; 62 percent is mountainous.

Beijing is flat but is not the easiest place to get around in on foot but was ideal for a bicycle until cars engulfed the city. Taxis are cheap and plentiful. For an adventure ride a bicycle. The main downtown area is around Changan Avenue, a super wide avenue that divides Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City. Off of this you can find hotels, office complexes, modern shopping malls, embassies and lots of construction cranes. There used to be some nice old neighborhoods here but they are mostly gone.

Beijing is a major transportation hub. Six Ring Roads serve the city. The 1st Ring Road is not an actual road, but refers to the original wall around the "Old City." The outer reaches of the city are served by five ring roads. The Second Ring Road roughly follows the foundation of the former inner city wall. It has eight lanes but is currently being widened. A Third Ring Road is a few kilometers further out. The final section of the Forth Ring Road opened in 2001. Most of the Olympics facilities are accessible from the Fourth Ring Road. A 228-mile network of roads built as “arms” for the ring roads are for the most part complete.

Beijing was designed with roads radiating north, south, east and west from Forbidden City. Eleven National Highways radiate out from city. All are major truck routes.The newer parts of the city are laid out in an orderly grid with wide boulevards and avenues intersected by small lanes and back streets. The older parts of town are not as well organized and easy to get lost in. Negotiating the main thoroughfares is not too difficult. Taking shortcuts is a bad idea. Subways reach many parts of the city. Buses and taxis run along the boulevards and avenues. Major shopping areas are major landmarks in their own right or are near large buildings (usually hotels) that also serve as landmarks. It is best to orient yourself according to these landmarks because streets often change name and the addresses are confusing.

The main roads in the tourist areas have signs in English but many of them change their name every few blocks. A detailed map with names in English and Chinese as well as subways stops and bus routes is essential. Before you head off to some place off the beaten path, it helps to have detailed written directions in both English and Chinese and the name of a landmark near your destination. To get back to your hotel bring a card with the name of your hotel in Chinese and English. Since taxis are cheap, it often worthwhile to take a cab if you don't want to walk. The subway is good and serving more and more destinations all the time. Buses are crowded.

Changan Avenue

Changan Avenue (between Tiananmen Square and the Forbidden City) runs through the main downtown area. Along it are bike lanes, hotels, office complexes, modern shopping malls, Stalinesque monstrosities, embassies and lots of construction cranes. There used to be some nice old neighborhoods around it but they are mostly gone. In the their places are new streets and buildings with New York City names like the Park Avenue and Soho apartment complexes. You can also find Central Park, Time Square, Little Italy and even Forest Hills.

Chang'an Avenue is a major thoroughfare in Beijing and showcase of Chinese Stalinist architecture and some modern architecture.Known as the east-west central axis of the city, the historic avenue extends nearly 45 kilometers from Tongzhou District in the east to Shijingshan District in the west while undergoin several name changes. The core section of Chang'an Avenue stretches 6.7 kilometers from Fuxingmen on the Western 2nd Ring Road to Jianguomen on the Eastern 2nd Ring Road. Along this section, there are more than 50 important and internationally renowned structures.

Bicycling in Beijing

Beijing from Space

Bicycles are popular in Beijing but not as common as they once were when cars were few in number. Cycling is risky is on busy streets. Bike lanes are available on some main streets. Bicycles can be rented from many hotels, or from places near the hotels. Or at least personnel at a hotel can tell you where you can rent a bike. Several million bicycles still fill some roads and bike paths on the sides of roads in Beijing although they have been largely displaced by motorized vehicles.

Beijing is relatively flat, which makes cycling convenient and gears not necessary. Visitors find cycling a convenient way to exercise and sight-see at the same time. Conventional Chinese bicycles are heavy and have no gears, but are sturdily made and comfortable. Western-style road and mountain bikes are now common sights. Nice bikes are sometimes stolen so make sure you have a good lock if you have such a bike.

The rise of electric bicycles and electric scooters, which have similar speeds and use the same cycle lanes, may have brought about a revival in bicycle-speed two-wheeled transport. It is possible to cycle to most parts of the city. Because of the growing traffic congestion, the authorities have indicated more than once that they wish to encourage cycling. There large number of dockless app based bikeshares such as Mobike, Bluegogo and Ofo.

Major roads serving the city are generally congested. National Road 109 also serves the city; is well maintained and lightly traveled. It has steep hills near the city but is favorable for cycling. Mountain bikes are recommended for city's more rural areas. Rental bikes are readily available from hotels, subway stations and popular tourist stops.

A Beijing New York Times reporter wrote: “Bicycles can be found on every street, and they come in an array of shapes, sizes and uses. There are bikes with cargo beds that carry everything from bags to trash to new sofa sets. There are electric bikes and miniature scooters. Children bounce on the luggage rack behind their parents, and older women teeter on even older bikes. No one wears a helmet." It is not uncommon to see bicycles with caged songbirds dangling from the handlebars.

In the Mao era bicycles were regarded as one of "three bigs" — along with a sewing machine and wristwatch. People placed their names on waiting lists for years to get them and took out loans form the factories where they worked to help pay for them. By the 1990s, bicycle use was declining in many places as more and more people gained access to cars. In 1998, bicycles were banned from East Xisi Street, near the Forbidden City to make it easier for car traffic. Violators were chased down by guards with bullhorns and red arm bands. The ban was extended to other streets later on. Many people were angered by the ban. Bicyclists were angry they had to take a longer route and environmentalists said it sent the wrong message at a time when Beijing has recording some of the world's worst air pollution.

Bicycle Riding in Beijing

“Beijing bicyclists pedal differently from their Western counterparts," Joost Polak wrote in the Washington Post. “They set their seats a bit low, lean almost backwards and pedal with the arch or even the heels rather than the ball of their feet, which plays their knees out on the upstroke."

Explaining how his Chinese friend shifted across six lanes of traffic in Beijing Polak wrote in the Washington Post, “Xian Fang, moved ahead to the first lane of cross traffic...Seeing a gap, she pushed through to the next lane, braked to a near standstill, them pumped her way across another lane. After a couple more lanes I began to see the gaps that seemed so clear to her. And then it was time to look in the other direction and work our way across the traffic coming from our left."

American Olympic cyclist Taylor Finney took his bike out for a spin on the streets of Beijing during the Olympics in 2008. He said he couldn't believe that none of the Chinese were wearing helmets. “I wore a helmet because I'm scared of Chinese drivers!” he said. “I’m scared even on a bus. There's no way I'm not wearing a helmet."

One Beijing cyclist told the Washington Post, “The drivers are very aggressive. They won't wait for you for a second. The road belongs to them now." Some studies indicate that the decline of bike usage may be short-lived as the practicality of a bicycles kicks in and the novelty of car driving wears off.

On riding a bicycle in Beijing compared to New York City, Edward Wong of the New York Times wrote: “It was always a joy biking through the city, definitely preferable to taking the subway, but it's no exaggeration to say that I had a close call on virtually all my rides. By comparison, biking in Beijing has been a breath of fresh air (or as fresh as air can be here.) The bike lanes give me a sense of security that was always absent from my experience in New York. As for the argument that bike lanes lead to automobile congestion, that seems absurd from a Beijinger's point of view. Some studies show that Beijing is now the most congested city in the world. There are many reasons for this, but I have yet to hear any transportation expert cite the bike lanes as a factor."

“No question that as Beijing has built more roads, drivers have expanded to fill them. But I fear that all of this braying has obscured John's point that it is not the presence of the lanes he resents, but the manner in which they are being foisted upon him. As he argues, “it should be put to a vote rather than being enacted via bureaucratic diktat." Bureaucratic diktats are something else that we in Beijing know well. It's fashionable these days to admire Beijing's ability to marshal public resources to do things efficiently, whether it's installing wind turbines on the hillsides or embarking on another eight (yes, eight) new subway lines this year. But the part worth envying is the ambition of a city to envision bold changes and investments — not the ostensible efficiency of a system that deprives people of the right to participate in those choice. As we see everyday here, knocking down houses without adequate due process, in order to modernize the city, might make those neighborhoods more hospitable, but it also has a toxic effect on the political health of the city. Good ideas are good enough to put to a vote."

Bike Lanes of Beijing

On bike lanes on both sides of the streets are filled with bikes, electric and gas-powered motorbikes, delivery tricycles and pedicabs traveling in both directions. Polak wrote," “They are almost always wide enough for cars to fit into. So they do. Sometimes they nip into the bike lane because all of the vehicle lanes are slowing. Sometimes the drivers pull over and park to make a cell phone call."

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Beijing has at least three definable species of bike lane. The most luxurious, which we'll call Business Class, is a ribbon of designated asphalt set off from the car world by a sidewalk and often a tree or two: The second variety, Economy Class, shares the roadway with cars and buses, but takes up the prized area beside the curb, monopolizing the space for parking that has John concerned." [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, March 11, 2011]

“The third species, which we'll call Economy Plus, has elements of both: a line of parked cars, a lane for bikes, and at least two lanes for autos. Pros and cons: Everybody gets their lane, but that has required widening some of Beijing's roads to at least seven lanes, and very often twice that, producing not so much roads as “exalting deserts of tarmac," as a visiting urban planner once put it. Along the way, the buildings on either side get leveled (with or without a fight) and neighborhoods are altered. None of this is the fault of the bike lanes — the roads are being widened, without question, for cars — but none of the options are without tradeoffs."

“Before cyclists start boarding flights for Beijing like the fellow travellers of yore, know that bicycle production has been falling since 1995 here, and the lanes have been gobbled up by cars ever since. The country has been rapidly losing its attachment to the human-powered two-wheeler that it first glimpsed in the late nineteenth century and regarded as a “foreign horse” or a “little mule that you drive by the ears." One of the replacements, I'm pleased to say, is the electric bike, which I've been driving by the ears for eighteen months and counting. Not surprisingly, I'm an ardent fan of the bike lanes and would seriously rethink my own e-bike evangelism if they disappeared. For a comparison of the situation on both sides of the Pacific, I turned to Ed Wong of the Times. He pedals all over this town, and did so as well in New York a decade ago, before bike lanes had taken off.

Traffic in Beijing

Traffic is heavily congested. Rush hour traffic speed are often between 10 and 15 mph — more or less the same as bicycling speed. Inadequate traffic management and increasing numbers of taxis and private vehicles contribute to congestion.

In the 1990s bicycles outnumbered cars by a large margin and traffic jams were largely unheard of. Now traffic jams are a fact of life and situation is expected to get worse before it gets better. As of 2007 three million cars were registered in Beijing and 1,200 new automobiles took to the streets every day (400,000 a year). By early 2011 there were 4.8 million vehicles in Beijing. The number may reach 7 million by the end of 2012. By contrast there are about 2 million vehicles registered in New York City.

Drivers complain that rush hour now lasts all day. Even though Beijing has highways with 10 and 12 lanes and six concentric ring roads it can take more than an hour to travel the 6½-kilometer diameter of the city center. To reduce congestion, car access to some streets is restricted, with vehicle only allowed to use these streets on desegrated days according to the numbers of their license plates. Beijing has not been as aggressive trying to reduce the number of cars as Shanghai, where licencing fees are as high as $7,000 per car.

According to ASIRT: Intersections with traffic lights generally have zebra crossings. Be alert. Most drivers assume pedestrians will yield to them, even when police are present. Some drivers play "chicken" with pedestrians. May blow horn and keep coming. Drivers are more likely to stop for large groups of pedestrians crossing a street. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

Traffic Restrictions in Beijing

Traffic entering the Beijing is restricted; based on last digit of vehicle license plate. On week days, vehicles with non-local license plates are not permitted to enter areas within the 5th Ring Road during rush hour (7:00am to 9:00am and 5:00pm to 8:00pm). Vehicles with special passport-type document are exempt from restrictions. Violators are fined and must leave by a specified route to avoid additional fine. Restrictions do not apply to inter-provincial passenger coaches and tourism vehicles. Police cars, military vehicles and ambulances also exempt when in service. Some roads are one-way during specified hours. Large road signs indicate times roads are one-way.

The system has put in place in 2008 before the Olympics. “The Global Times reported in 2018: “Beijingers have come to terms with the quarterly cycles of car plate-based restrictions. The policy requires automobiles with end numbers 1 or 6, 2 or 7, 3 or 8, 4 or 9 and 5 or 0 respectively from Monday to Friday to refrain from driving. The specific days of road restrictions changes on a quarterly basis, sometimes leading to some minor confusion and fines incurred by car owners. [Source: Pearl Chen, Global Times, April 17, 2018]

“As of now, it is likely that the car plate road restriction policy will continue in Beijing well into the future. Beijing has launched the "I volunteer to reduce car driving by an additional day" WeChat account, which offers small-amount, nominal monetary compensation for any car owners who volunteer not to drive their cars even when they are not restricted. Though it is just a small-scale pilot, the innovation indicates the goodwill of city planners dedicated to fighting against congestion and pollution.

Taxis in Beijing

Old Taxis Taxis are fairly plentiful and available. Taxis can be hailed or picked up at hotel taxi stands. Drivers generally wait near tourist attractions or subway stops. Most hotels in Beijing have English-speaking dispatchers for taxi stands. Fares are relatively low. Between 11:00pm and 5:00am, there is also a 20 percent fee increase. Use metered taxis and make sure the meter is turned on before departing. Ask for a receipt. Fares are often high for foreign tourists. Agree on fare before boarding. If over-charged, do not argue with driver, especially when alone. Record license number; call police later [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

Metered taxi in Beijing start at ¥13 (US$1.84) for the first 3 kilometers (1.9 miles), ¥2.3 (33 US cents) Renminbi per additional 1 kilometer (0.62 miles) and ¥1 per ride fuel surcharge, not counting idling fees which are ¥2.3 (¥4.6 during rush hours of 7–9 am and 5–7:00pm) per 5 minutes of standing or running at speeds lower than 12 kilometers per hour (7.5 mph). After 15 kilometers (9.3 miles), the base fare increases by 50 percent (but is only applied to the portion over that distance). Rides over 15 kilometers and between 11:00pm and 6:00pm have both the late night fee and long distance fee, for a total increase of 80 percent. Tolls during trip should be covered by customers and the costs of trips beyond Beijing city limits should be negotiated with the driver. The cost of unregistered taxis is also subject to negotiation with the driver.

Most taxis are Hyundai Elantras, Hyundai Sonatas, Peugeots, Citroëns and Volkswagen Jettas. Different companies have special colours combinations painted on their vehicles. Usually registered taxis have yellowish brown with another color such as blue, green, white or purple. green. According to ASIRT: “Use registered taxis when possible. License plates begin letter "B". Drivers are generally honest. Trips may take longer than expected, due to congestion. Drivers may take detours due to travel restrictions in central Beijing. Some drivers are new immigrates to the city; do not know the city well. Drivers seldom speak or read English; bring a map or have your destination written down in Chinese.

Avoid using "black cabs" (unregistered taxis). License plates begin with letters other than "B". "Black cab" drivers may drop foreign tourists at wrong location. In a few cases, have taken tourists to remote locations and robbed them. Registered taxis may be scarce in more remote areas.

Motorcycle taxis are widely used and often idling outside Metro stations: Drivers may demand high fee; agree on fare before boarding. Not recommended due to high road risk. Pedicabs are generally 3-wheeled vehicles, powered by bicycle or motor. Provide transport over short distances. Built for two passengers, seated behind driver. Also known as cycle-rickshaws or auto-rickshaws.

Beijing Subway

New Tanjin trains

The Beijing Subway began operating in 1969 and was greatly expanded in the 1990s and 2000s. It has 22 lines, 370 stations, and 608 kilometers (378 miles) of lines. It is the longest subway system in the world and has the most riders in the world (3.66 billion in 2016). The subway is still expanding at a prodigious rate and is expected to reach 30 lines, 450 stations, 1,050 kilometers (650 miles) in length by 2022. When fully implemented, 95 percent of residents inside the Fourth Ring Road will be able to walk to a station in 15 minutes. The Beijing Suburban Railway provides commuter rail service to outlying suburbs of the municipality.

In December 2014, the Beijing Subway switched to a distance-based fare system from a fixed fare for all lines except the Airport Express. Under this system a trip under 6 kilometers costs ¥3.00 (US$0.49), with an additional ¥1.00 added for the next 6 kilometers (3.7 miles) and the next 10 kilometers (6.2 miles). Before December 2014, rides were a flat fare of ¥2.00 (US$0.31 USD), with unlimited transfers on all lines except the Airport Express, making it the most affordable rapid transit system in China. Tickets are purchased with touch screens. Once you figure out how to switch the ticket machines to English everything is easy. You select the station you are going to, the number of tickets and method of payment, put in your money and out comes the tickets and change. Paper tickets were phased before the Olympics.

The Metro system is extensive. Frequent service; often overcrowding is common. Schedules and signs for subway stops are in English. The subways operate from 5:30 am to 11:00pm. The cars are clean and the service is quick and efficient. The trains are usually not that crowded except at rush hour, when special employees whose job is to shout "hurry up" and "don't push" are on duty.

Huma Sheikh wrote in Xinhuanet: “The subway is very well equipped with electronic signboards almost everywhere, consistently popping out destinations both in Chinese and English as each train arrives. The announcement also follows the arrival of the next train, again both in English and Chinese and there is hardly any chance of getting lost, even for a first-timer who has just arrived in China. Every station has moving walkways for easier movement, escalators and a host of other relevant facilities amid huge crowds — which is no wonder to find in Beijing, the capital of the world's most populous country.[Source: Huma Sheikh, Xinhuanet April 1, 2009]

Parallel to Lines 1 and 2 are underground highways built in the 1960s, when tensions with the Soviet Union were high, to whisk high-ranking official out of the city in the event of a nuclear attack. Today cadres use the highway to avoid traffic to reach the golf course or their weekend bungalows. Transfers between lines are free. Beijing had eight subway and light rail lines in 2009 and 170 stations and 250 miles of track in 2011. Three new subway lines built at a cost of $3.3 billion opened three weeks before the Olympics in 2008. Serving Beijing’s international airport and the Olympic Green, these subways expanded the reach of Beijing’s subway system by 40 percent to 201 kilometers. Subway Maps: Joho Maps Joho Maps ; Beijing Subway Map: Urban Rail urbanrail.net

Beijing Subway Lines

1) The east-west line (Line 1) runs through Tiananmen Square, Wangfujing and the World Trade Center before heading to the eastern and western reaches of the city. 2) The loop line (Line 2) largely follows the layout of the former inner city wall and the second ring road. It stops at Beijing Zhan, near the Friendship Store and near Yonghe Gong and Qiamen.

3) Line 5 runs north and south just east of the city center and passes by the Temple of Heaven and Lama Temple. 4) The L-shaped Line 10 passes south of the Olympic Green and follows the Third Ring Road through the Embassy District. 5) The Olympic Branch Line extends off Line 10 with three stops at the Olympic Green.

6) Line 13, an aboveground light rail, extends to the north of city, connecting the northern suburbs with the east-west line. 7) Line Batong extends the east-west line to the east. 8) The new Airport Line connects the airport with Lines 1, 10 and 13 covers 28 kilometers in 20 minutes. It is elevated and offers good views of Beijing.

Airport Express subway line links the airport and city center. It has only four stops: Dongzhimen, S anyuanqiao, Terminla 1 and Terminal 2. New subway lines to more remote districts has shortened commute times to city center. Plans call for the Beijing subway system ultimately stretch for 561 kilometers — with 19 lines reaching every nook and cranny of the city. Plans to build and expensive magnetically-levitated train in Beijing from the international airport similar to the one in Shanghai were scrapped after it was decided tp build the Airport Line.

Buses in Beijing

Public buses are chief means of local transport There are nearly 1,000 public bus and trolleybus lines in Beijing, city, including four bus rapid transit lines. Fares are low. Obtaining a public transportation card at a metro station reduces fare. Standard bus fares are as low as ¥1.00 when purchased with the Yikatong metrocard. .Local buses provide service in city and suburbs. The buses are often overcrowded, especially during rush hour. Service on most routes is more frequent on major holidays. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

The buses in Beijing are a little difficult for tourists to handle. The routes are hard to sort out and English is generally not used on signs or the exterior of buses. According to to ASIRT: “Local bus fleet is being updated. New buses are air- conditioned in summer and heated in winter. Bus network is difficult to use unless fluent in Mandarin or Chinese. Bus personnel speak little English. Stops are seldom announced in English. Bus stop signs are in Chinese. For assistance, call English-speaking operators at Beijing Public

Transportation Customer Helpline. Phone: 96166.

Bus route information:

Routes 1-300 serve city center. Routes 200-299 are night buses.

Routes 301-899 link city center with areas beyond the 3rd Ring Road.

Routes 900-999, link city's urban districts with its rural districts (Changping, Yanqing, Shunyi, etc).

Travel on Three Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) buses may be faster and less crowded than on metro. BRT corridors are in service, and a fourth line is under construction. BRT Line 1 is most heavily used. Runs along Nan Zhongzhouxian (South Central Axis Line); links Qianmen and Demaozhuang.Qianmen is the common name for Zhengyangmen, a southern gate in "old city's" wall.

Minibuses commonly provide transport in city's rural areas. Fares are low; based on distance. Available mainly on routes linking train stations and tourist sites. Can be hailed. Passengers can disembark anywhere along route. Are slower than buses due to frequent stops. Fares are slightly higher than bus fares.

Tourist Buses provide one-day tours to the Great Wall of China and other popular attractions near the city. Purchase tickets at "Beijing Hub of Tour Dispatch" dispatch centers in Xuanwumen and Tiananmen Square to get lowest price. Tourists travel free when purchasing admission tickets for destinations prior to boarding. Information in English contacts Beijing Trip: beijingtrip.com

Roads in Beijing

Beijing is a major transportation hub. Six Ring Roads serve the city. The 1st Ring Road is not an actual road, but refers to the original wall around the "Old City." Eleven National Highways radiate out from city. All are major truck routes. These national highways radiate to Shenyang, Tianjin, Harbin, Guangzhou, Zhuhai, Nanjing, Fuzhou, Kunming and other parts of China. Junctions may be difficult to navigate. Construction on ring roads may cause serious congestion on other arterial routes serving the city.

The six-lane Airport Expressway Airport Expressway links city center and the airport. The Road splits off of the northeastern section of 3rd Ring Road at Sanyuanqiao. It is often heavily congested. The G112 begins in Gaobeidan, Tianjin and forms a long ring road around Beijing. Speed limit on Beijing's segments of Jingjintang and Jingha Expressways is 90 km/h (56 mph), which is lower than speed limits on other expressways or express routes.

Main Highways:

China National Highway 101 (G101) to Chengde and Shenyang.

G103 to Tanggu. Exits from Fenzhongsi district.

G104 to Fuzhou.

G105 to Zhuhai and Macau.

G106 to Guangzhou.

G107 to Shenzhen.

G108 to Kunming. Also known as Jingyuan Road.

G109 to Lhasa in Tibet.

G110 to Yinchuan.

G111 to Heilongjiang Province.

Ring Roads in Beijing

Beijing city has six ring roads (some sections are raised highways) that allow for easier access around the city and to the outskirts. The 1st Ring Road is not an actual road, but refers to the original wall around the "Old City." The ring roads help but do not reduce by that much overall traffic congestion, caused by a proliferation of taxicabs and privately owned vehicles on city streets. Junctions may be difficult to navigate. Construction on ring roads may cause serious congestion on other arterial routes serving the city.

2nd Ring Road is very busy and generally in good condition. According to ASIRT: No traffic lights; intersections are grade separated. Although heavily congested, road is seldom gridlocked. Traffic backups are common, especially near exit for Airport Expressway. Road is least congested between Caihuying and Zuo'anmen. Access to alternate routes is limited. Road has few connections with Beijing expressways. Speed limit on the road is 80 km/h, except in section between Xiaojie Bridge and Dongzhimen and other sections with sharp curves. Speed is closely monitored by speed cameras and police officers. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

“Digital display boards give information on current traffic conditions. Text is in Chinese. Color indicates average travel speed on a road, where yellow = 20-50 km/h; red = under 20 km/h. Has pedestrian overpasses; used by pedestrians, cyclists and motorcyclists.Located near perimeter of city center; runs along moat that surrounded the "old city" wall. Many exits are named for wall's gates. A large section of Metro, Line 2 runs under the road; has Metro station exits on both sides of the road, except at Andingmen station.”

3rd and 4th Ring Roads: The Airport Expressway links city center and the airport and splits off of the northeastern section of 3rd Ring Road at Sanyuanqiao. Often heavily congested. The fourth ring road was largely built in the 1990s to be a high-capacity transport corridor, linking Jingjintang Expressway, Jingshi Expressway, Badaling Expressway and Capital Airport Expressway. Heavily congested. Often gridlocked. Intersections with local roads have traffic lights. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

6th Ring Road: is a 4-lane, dual expressway and toll road that is generally in good condition. According to ASIRT: A toll road; lightly traveled, except near exit at Xishatun, where traffic jams may occur. Speed limit: Minimum 50 km/h (31 mph), maximum 100 km/h (60 mph). Truck drivers often drive below speed limit and car drivers frequently exceed speed limit. Southwestern section, 6th Ring Road: Has no passing lanes. Speed limits: Left lane: Minimum 80 km/h(50 mph)- maximum 100 km/h (60 mph). Right lane: Minimum 60 km/h (37 mph), maximum 100 km/h (60 mph). Right lane is for cars only. Western section, 6th Ring Road: Links Liangxiang and Zhaikou. Passes through rugged, mountainous terrain in Beijing's Mentougou District. [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011]

Badaling Expressway (G25): Road to the Great Wall of China

The Badaling Expressway (G025) starts as a six-lane divided highway, generally in good condition, and is often used to get to the Great Wall of Chinese. According to ASIRT: After Beijing's Nankou district, road is a four-lane divided highway. Links Beijing with the Badaling section the Great Wall of China. Begins near Madian Bridge on Northern section of Beijing's 3rd Ring Road, and passes through many of Beijing's residential and industrial zones [Source: Association for Safe International Road Travel (ASIRT), 2011].

“Due to mountainous terrain, road splits into inbound and outbound sections in Juyongguan. Outbound section has 3 exits to the Great Wall of China; inbound section has none. When traveling inbound, take Exit 20 and follow route to the "Wall." Inbound and outbound sections rejoin after Badaling and continue to Yanqing, where road becomes the Jingzhang Expressway. Some maps include the road in Jingzhang Expressway, a road linking Beijing and Zhangjiakou in Hebei province. Has exits to northern sections of Beijing's 3rd, 4th, 5th and 6th Ring Roads, Huilongguan, Changping, Nankou, Badaling and Yanqing.

Travel conditions on specific sections: Congestion is most common from Madian to Huilongguan, especially near Shangqing Bridge. Often gridlocked from Madian to Jianxiang. Out-bound traffic often congested from Jianxiang to Qinghe Toll Gate. Expect long waits at Huilongguan exit during rush hours. Travel may be slow traffic after Juyongguan, due to mountainous terrain. On outbound section, fog is common on 49 and 50 kilometers stretches and from Shahe to Xisanqi, especially at night. Road risk is high on sections in urban and suburban Beijing.

Badaling Expressway’s "Valley of Death": An inbound section of Badaling Expressway is known as the "Valley of Death". According to ASIRT: “The 50-55 kilometers section; begins shortly after road splits at Badaling. Section has a high road crash rate. Speed limit drops to 60 60 km/h (37 mph) for light-duty vehicles and 40 km/h (25 mph) for trucks, and is strictly enforced. Speed cameras are numerous; fines are high. Section includes a series of switchbacks (tight, downwardly spiraling curves), indicated by a "serial downgrades" sign. Road safety features include several Emergency "Brake-Fail" areas (upward sloping banks of gravel to slow vehicles that experience a mechanical failure and are unable to slow down or stop). Park near a "Brake-Fail" area when vehicle needs to be checked for any mechanical problems.[Source: ASIRT]

Badaling Expressway Exits for the Great Wall of China: Juyongguan Exit (Exit No. 15): Provides access to The Great Wall at Juyongguan Pass. Shuiguan Exit (Exit No. 16): Provides access to The Great Wall at Shuiguan, a lesser known section of the Wall. Road is extremely steep; allows travelers to see unrepaired sections of the Wall. No return ramp to expressway. Take minor roads back to Juyongguan to continue on expressway. Badaling Exit (Exit No. 18): Leads to Wall's most well known section. Parking may be available. [Source: ASIRT]

Image Sources: 1) CNTO (China National Tourist Organization; 2) Nolls China Web site; 3) Perrochon photo site; 4) Beifan.com; 5) tourist and government offices linked with the place shown; 6) Mongabey.com; 7) University of Washington, Purdue University, Ohio State University; 8) UNESCO; 9) Wikipedia; 10) Julie Chao photo site.

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), UNESCO, Rough Guide for Beijing, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in June 2020