XIAN

XIAN (1,000 kilometers southwest of Beijing, 1,400 kilometers west of Shanghai) was the capital of China from 221 B.C. to A.D. 907, and today it is one of China's premier tourist attraction. Located in southern Shaanxi Province, it is sometimes called the "Sleeping Town of China" because most of the country's first emperors and their wives and concubines were buried here or nearby. Xian was the starting point of the Silk Road and home of the Banpo people, a Neolithic culture that lived in the area 8,000 years ago and are regarded by some as China’s first civilization. Xian is also spelled Xi’an; in ancient times it was known as Changan, or Chang’an. It has also been spelled Hsi'an and Sian.

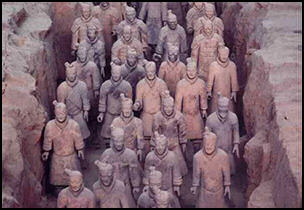

At first glance present-day Xian doesn't seem particularly appealing. The capital of Shaanxi. Province and the 10th largest city in China, it is home to over 7 million people (13 million in the Metro) Area and is an important industrial and trading center with lots of dust and grime. Plus, it is touristy. Along with it tombs and terra-cotta soldiers is a 550-seat Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant, a Sheraton, a Hyatt, a Holiday Inn, a fairly large airport (45 kilometers away and completed in 1993), large construction projects, new department stores with glass panels, shopping malls with plastic trees and a brick-paved shopping street with neon lights and welcome signs in English. Some of the souvenir shops in Xian used to pay a small salary farmers who discovered the terra cotta army in their field in 1974 to sign autographs for visitors to their shops. But not of all is bad. Tang Dynasty (618-906) music and dance is performed every night and the food in the ancient Muslim is fabulous.

Since the 1980s, Xian has been a centerpiece of the economic revival of inland China and now serves as an important cultural, industrial and educational centre of central-northwest China. There are facilities for research and development, national security and even space exploration. It is the most populous city in Northwest China, as well as one of the three most populous cities in Western China, the other two being Chongqing and Chengdu. In 2012, Xian was named as one of the 13 emerging megacities in China.

Web Sites: Wikipedia Wikipedia Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Lonely Planet Lonely Planet Tourist Office: Xian Tourism Administration, 159 Beiyuanmen, 710003 Xian, Shaanxi, China, tel. (0)- 29-729-5632, fax: (0)- 29-729-5607; Maps of Xian: chinamaps.org ; Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books; Getting There: Xian is accessible by air and bus and well-connected by train to the rest of China. Travel China Guide Travel China Guide

See Separate Articles: TERRA COTTA ARMY AND TOMB OF EMPEROR QIN SHIHUANG factsanddetails.com SIGHTS IN XIAN: ITS WALL, MUSLIM QUARTER AND OLD TOWN AND PAGODAS factsanddetails.com ; NEAR XIAN: TOMBS, NEOLITHIC VILLAGES, IMPERIAL POOLS, SACRED HUASHAN AND THE WORLD’S DEADLIEST HIKE factsanddetails.com ; SILK ROAD SITES IN THE XIAN AREA factsanddetails.com ; SHAANXI: YAN’AN RED TOURISM, GOLDEN MONKEYS AND XI JINPING’S CAVE HOME factsanddetails.com

Orientation and Layout of Xian

Xian is situated in the center of the Guanzhong Plain in east-central China. The city borders the northern foot of the Qin Mountains (Qinling) to the south, and the banks of the Wei River to the north. Hua Shan, one of the five sacred Taoist mountains, is located 100 kilometers away to the east of the city. Not far to the north is the Loess Plateau. The Yellow River is to the east.

Most of Xian's premier tourist sites are located outside of town. In the city itself are Buddhist, Taoist, Tibetan and Confucian temples (some are in ruins, others are restored). The old part of the city is partly surrounded by a medieval wall. Dong Dajie is Xian's main shopping avenue. Xi’an Bell and Drum Tower Commercial Center, located in the city center, is the most popular and largest commercial center in Xi’an. There are more than a dozen shopping malls as well as large supermarkets, amusement centers, cultural plazas and restaurants. It is spread among four main streets: The Muslim Quarter is beside the Drum Tower. Xian has many areas that are easily accessible on foot. In many commercial and tourist areas, city, especially in the shopping and entertainment districts around the Bell Tower, underpasses and overpasses have been built for the safety and convenience of pedestrians.

Xian Railway Station, traditionally the main train station for the city, is just north of the walled city. The new Xi'an North railway station, the station for the fast trains, is situated a few kilometers to the north. Similar to Beijing’s 798 and Shanghai’s 1933, Xi'an has an art district called Textile Town, the center of the town’s old textile area. Major industrial zones in Xi'an include: Xi'an Economic and Technological Development Zone and Xi'an Hi-Tech Industries Development Zone. The Xi'an Software Park, within the Xi'an Hi-Tech Industries Development, is home to over 1,000 companies and 100,000 employees.

History of Xian

Xian is known all over the world as the home to the 2,200-year-old Terracotta Army and the eastern terminus of the Silk Road and some regard it as great ancient city along with Athens and Rome. It has been the capital of between 10 and 13 dynasties — including the Qin, Han and Tang– depending how the dynasties are defined and has been a focal point for international exchange between China and other countries.

The Xian area has a long history. Lantian Man was discovered in 1963 in Lantian County, 50 kilometers southeast of Xian, and dates back to at least 500,000 years ago. The 6,500-year-old Banpo Neolithic village — which contains the remains of several well organized Neolithic settlements that some regard as the first Yellow River Valley civilization — was discovered in 1953 on the eastern outskirts of the city.

Xian became a cultural and political centre of China in the 11th century B.C. with the founding of the Zhou dynasty. The capital of Zhou was established in the twin settlements of Fengjing and Haojing, together known as Fenghao, located on opposite banks of the Feng River at its confluence with the southern bank of the Wei in the western suburbs of present-day Xi'an. Remains of carriages and horses have been unearthed in Fenghao. The true founding of Xian, some say, took place when Emperor Qin Shihuang unified China and made Xingyang (near Xian), the capital of the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.). The terra-cotta army was built for Emperor Qin Shihuang along with a huge still untouched mausoleum.

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “There was no China, only a collection of squabbling states, before the short-lived but powerful Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.) brought terror and unity to the land. The Qin were the first to stake their capital here, on the Wei River, but the country’s Han majority — now the world’s biggest ethnic group, more than a billion strong, representing nearly one out of every six people on earth — take their name from the Qin’s successor, the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. to A.D. 220), which raised a new capital nearby, Chang’an, in 202-200 B.C. Not long after, the emperor Wudi sent an envoy to the West: the dawn of China’s engagement with civilizations beyond its frontiers. Where the landing of Europeans in the Americas in the 15th century was sudden and calamitous, the Eurasian cultural exchange happened slowly, over centuries, between nations meeting as relative equals.” [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

The Han emperors that followed Emperor Qin kept their court in Xian area and established Chang'an. After years of chaos and upheaval, the Sui emperors built a city called Daxing in the A.D. 6th century on the ruins of Xian. Xian had its name changed back to Chang’an when it was capital of the Tang Dynasty (618-906) and the gateway to the Silk Road. Its grid-like street layout was a model for Kyoto and Nara in Japan. Under the Tang emperors, Chang'an grew into a dynamic metropolis with two million people and great buildings, art and literature. Financed in part by wealth from Silk Toad trade, it rivaled Constantinople in its magnificence. The Song emperors established a new capital in Kaifeng in the 10th century and Xian went into a period of decline. Xian was visited by Marco Polo in the 13th century but by that time the capital of China was in Beijing. Little of the old city remains today. In more recent history, Xian is remembered as the scene of the communist kidnapping of Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek in 1936.

Xian During the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.)

During the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.), Emperor Qin Shi Huang Qin Qin established his capital in Xingyang, north of the Wei River near present-day Xian. In an effort to weaken the feudal aristocracy by taking them away from their land Emperor Qin Shi Huang Qin transported 120,000 wealthy families from all over his empire to his Xingyang. In Xingyang, Qin showed off his power by building replicas of the palaces the aristocrats left behind (it is said Qin built an additional 270 palaces for himself, many of which were built in accordance with the layout of the stars). In all of China Qin, reportedly built 700 palaces, filled with treasures and beautiful women from all over China. Unfortunately from an archeological point of view no remains of any of these palaces have survived.

During the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.), Emperor Qin Shi Huang Qin Qin established his capital in Xingyang, north of the Wei River near present-day Xian. In an effort to weaken the feudal aristocracy by taking them away from their land Emperor Qin Shi Huang Qin transported 120,000 wealthy families from all over his empire to his Xingyang. In Xingyang, Qin showed off his power by building replicas of the palaces the aristocrats left behind (it is said Qin built an additional 270 palaces for himself, many of which were built in accordance with the layout of the stars). In all of China Qin, reportedly built 700 palaces, filled with treasures and beautiful women from all over China. Unfortunately from an archeological point of view no remains of any of these palaces have survived.

Qin recruited competent administrators and ruled his kingdom through a vast network of hierarchal administrations that were overseen by provincial units run by governors appointed from Xian. He also kept a tight rein on the military. Only generals with the Emperor's half of a split bronze tiger received permission to secure weapons and procure troops. Xianyang was the approximate site of the Western Zhou capital.

On the administration of Emperor Qin’s empire, Dr. Robert Eno of Indiana University wrote: “Within each of the 36 commanderies a much larger number of counties were demarcated. Each county was administered by a chief magistrate, who supervised subordinate magistrates in every city, town, and significant village within his domain. The city magistrate was the lowest level of government appointed administrator, but his locally recruited staff and representative headmen designated for neighborhoods and small villages also served the central government. [Source: Robert Eno, Indiana University indiana.edu /+/ ]

“To ensure that no wealthy clans who represented existing sources of local power could rival the government's influence in the counties, the Qin court financed a massive removal of the patrician clans to the region surrounding Xianyang, where they could be closely supervised. The historical annals tell us that 120,000 clans were relocated in this way, and provided with incomes that would keep them uninterested in fomenting revolt. The walls of their former estate fortress-cities were demolished, both the inner walls surrounding their palaces and the outer walls of military defense, and a massive program to collect and melt down weapons was instituted – there was to be no more civil war in China!” /+/

Under Emperor Qin, a number of public works projects were undertaken to consolidate and strengthen imperial rule. These included building a network of roads that fanned in out in all directions from Xingyang and constructing a network of canals that grew into greatest inland water communication system in the world. He even fixed the length for carriage axles so the wheels of carts would fit into the ruts of the roads. During the brief rule of the Qin, the government sponsored the construction of over 6,500 kilometers of highways and built large sections of the Great Wall of China..

Xian During the Han Dynasty (206 B.C. -A.D. 220)

The Western Han Han (206 B.C. - A.D. BC–9) built their capital of Chang'an (meaning "Perpetual Peace") on southern side of the Wei River in an area that roughly corresponds with the central area of present-day Xi'an. During the Eastern Han (A.D. 25–220), Chang'an was also known as Xijing ("Western Capital") as the main capital at Luoyang was to the east.

According to the Metropolitan Museum of Art: “After the civil war that followed the death of Qin Shihuangdi in 210 B.C., China was reunited under the rule of the Han dynasty, which is divided into two major periods: the Western or Former Han (206 B.C."9 A.D.) and the Eastern or Later Han (25–220 A.D.). The boundaries established by the Qin and maintained by the Han have more or less defined the nation of China up to the present day. The Western Han capital, Chang'an in present-day Shaanxi Province—a monumental urban center laid out on a north-south axis with palaces, residential wards, and two bustling market areas—was one of the two largest cities in the ancient world (Rome was the other). [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org\^/]

The remains of Han-era Chang'an, including a mint, kilometers of mud-and-brick city walls punctuated with gates, several imperial palaces, and a variety of other official buildings and residences, have been unearthed under modern Xian'. Han Dynasty cash coins—known as wu zhu coinage— are quite plentiful despite being over 2,000 years old. The reason for this is that billions of them were produced at a massive Han Dynasty mint in Shanglinyuan from brick and clay molds. The ruins of Shanglinyuan are a kilometers miles from Xian. [Source: Richard Geidroyc, World Coin News, December 11, 2012 =]

In October 2010, Chinese scientists announced that ancient Chinese emperors living in inland China may have dined on seafood that came from the eastern China coast more than 1,600 kilometers after investigating an imperial mausoleum that dates back 2,000 years. “We discovered the remains of sea snails and clams among the animal bone fossils in a burial pit," Hu Songmei, a Shaanxi Provincial Institute of Archaeology researcher told Xinhua.

Disputes among factions, including the families of imperial consorts, contributed to the dissolution of the Western Han empire in 9 B.C. . A generation later, China flourished again under the Eastern Han dynasty (25–220 A.D.), which ruled from Luoyang, a new capital farther east in present-day Henan Province.

Chang’an (Xian) During the Tang Dynasty

Sui Dynasty (581–618) brought the capital of China back to Xian, building a city called Daxing on the ruins of Xian. Xian had its name changed back to Chang’an when it was claimed by the Tang Dynasty (618-906) and it became the gateway to the Silk Road as it was under the Han.

Changan, by some estimates was the most populous city in the world at the time, the seat of power for the Tang imperial court, and a center of art, fashion, and culture.

Under the Tang Emperors, Chang'an became a thriving metropolis and a hub of international trade filled with merchants, foreign traders, missionaries from numerous religions, acrobats, artists and entertainers. It was home to as many as two million people at a time when no city in Europe had a population of more than a few hundred thousand. The city was linked to the rest of China through a network of canals and toll roads which brought more riches and taxes into Chang'an.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: ““Xi’an is an inland city about 800 miles northwest of Shanghai. From within its walls, caravans once set out carrying silk, perfumes, bronze mirrors and jade — goods and artistry that would eventually make their way to the great cities of Samarkand, Damascus and Constantinople; other caravans arrived from the West, bringing grape seeds, glassware, horses and gemstones. The Tang poet Bai Juyi compared the city’s layout to “a great chessboard.” Chang’an’s greatest avenues were 482 feet wide — three times the breadth of New York City’s Broadway. Later dynasties preferred more sober palettes, but under the Tang, civic architecture shone with color. Writers and artists celebrated the bluish stones of the capital’s winding Dragon Tail Way, the brilliant shades of the flower gardens of its mansions and the vermilion walls and flagstones studded with precious gems of the Palace of Great Luminosity.[Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Within Chang’an commerce and cultural ideas thrived and spread through trade to Europe, Korea, and Japan. In addition to the instruments of civilization, exports included silk textiles, wine, ceramics, metalwork, tea, and medicines, as well as delicacies such as peaches, honey, and pine nuts. Foreign merchants supplied the Tang elite with horses, leather goods, furs, gems, textiles, ivory, and rare woods. Tang China was cosmopolitan and tolerant, welcoming new ideas and other religions, and, in this environment, literature, painting, and the ceramic arts flourished." . [Source: “Reflections of a Golden Age: Chinese Tang Pottery," McClung Museum, December 13, 1997 |::|]

Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen of the Theater Academy Helsinki wrote: “Changan, was a well organised cosmopolitan city, where international embassies and traders had their own, designated quarters. The city bustled with Central Asian horsemen, international traders, many in their national costumes, as well as elegant beauties with tiny, painted lips, all of them immortalised in the Tang-period terracotta statuettes. The terracotta figurines also give enlightening information about the many forms of music, dance, mimes and other entertainment which were in vogue during that time." [Source:Dr. Jukka O. Miettinen, Asian Traditional Theater and Dance website, Theater Academy Helsinki]

Cosmopolitan culture flourished. Tens of thousands of foreigners lived in major Chinese cities. Women held high government offices, played polo with men and wore men's clothes. Chinese intermarried with nomadic peoples. Foreigners such as Turks rose to high positions in the civil service and the military.The economy changed a great deal in the Tang and Song dynasties, going from what was basically a subsistence economy to one in which peasantry was active in local and long-distance trade and non-food crops such as silk were produced on a large scale.

Chang’an was the Tang Empire was weakened the An Lushan Rebellion (755 – 763) and natural calamities. It was sacked during the Huang Chao Rebellion (874–884). Although the rebellion was defeated by the Tang, the dynasty never recovered from that crucial blow, weakening it for the future military powers to take over. The Song Dynasty (960-1279) established their court at a city that had not previously served as a dynastic capital — Kaifeng in China's midlands, just south of the Yellow River. After than Chang’an fell into decline.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: ““In the early 880s, Chang’an was sacked and the palace burned by an army rebelling against the Tang. The Sinologist Edward H. Schafer, in his 1963 paper “The Last Years of Ch’ang-an,” recorded how soldiers pillaged the city and occupied it for more than a year before being driven out; they looted it and left, “dripping gems along the road.” By 904, Schafer wrote, Chang’an was nothing but earth heaps and wasteland. A hundred years later, the palace would not appear in Song dynasty gazetteers. The old capital had disappeared everywhere but in ancient poems. [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Xian and the Silk Road

Xian served as the eastern gateway to the Silk Road under the Han and Tang Dynasties.According to the Asia Society Museum: “By the late second century B.C., military colonies were established in Gansu to protect the trade routes from nomadic incursions. These colonies became important trading posts on the Silk Road. The main route led from Chang'an (modern Xian) through Lanzhou, Wuwei, Zhangye, Jiuquan to Dunhuang and was protected by a Han extension to the Great Wall. “

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “In the seventh and eighth centuries A.D.,” Chang’an “was the center of not only China but the globe — the eastern origin of the trade routes we call the Silk Road and the nexus of a cross-cultural traffic in ideas, technology, art and food that altered the course of history as decisively as the Columbian Exchange eight centuries later. A million people lived within Chang’an’s pounded-earth walls, including travelers and traders from Central, Southeast, South and Northeast Asia and followers of Buddhism, Taoism, Zoroastrianism, Nestorian Christianity and Manichaeism. All the while, Shanghai was a mere fishing village, the jittery megapolis of the future not yet a ripple on the face of time. [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“The Roman Empire spent a fortune in its lust for Chinese silk, a scandalous cloth that some critics believed left women as good as naked and that was all the more desirable for being difficult to procure. But the Chinese had wants, too: horses from Central Asia for their armies. And as the Romans fantasized about a land beyond their horizons, the Chinese exalted the otherness of the countries to their west. In “The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A Study of T’ang Exotics” (1963), the American Sinologist Edward H. Schafer writes of Chinese aristocrats enthralled by the customs of erstwhile “barbarians”; one moony prince set up a Turkish camp on palace grounds and sat there dressed like a khan, slicing boiled mutton with his sword. Soon, Western influence had become so pervasive that the early ninth-century poet Yuan Zhen warned about the risk of losing Chinese customs in the quest for crass novelties:

“Ever since the Western horsemen began raising smut and dust, Fur and fleece, rank and rancid, have filled Hsien [Chang’an] … Women make themselves Western matrons by the study of Western makeup; Entertainers present Western tunes, in their devotion to Western music.

Muslims in Xian

Over 99 percent of Xi'an residents are Han Chinese. The 50,000 or so Muslim Hui make up the largest minority. Despite their small size they exert a strong influence on the city. Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: “ “As we walk, we pass a man in a white skullcap standing on a ladder, daubing paint on a restaurant sign. I begin to notice other signs with little scars: a swath of paint or tape or otherwise improvised appliqué to hide the Arabic script and symbols that vouch for the cooking as halal — coverings mandated by the government as part of a crackdown on Islamic expression.

“Within Xian, Hui and Han alike eat roujiamo, the Chinese hamburger: meat tucked into flatbread that’s been crisped on the grill until it shows tiger skin on one side — shades of orange and black — and a chrysanthemum whorl on the other. The Han make it with long-braised pork, doused with a spoonful of its own broth, and the Hui with beef or lamb, stewed, then salted and dried.

“The cultural heritage of minorities can be tolerated and even celebrated, like the food in Xian’s Muslim Quarter, so long as the deeper rituals behind it remain hidden. One folk tale collected in the 1994 anthology “Mythology and Folklore of the Hui, a Muslim Chinese People” tells of Hui men who journey to Chang’an during the Tang Dynasty (618-906) and are permitted to take Han wives. When the wives’ parents ask what the Hui are like, the women confess that they can’t understand what their husbands are saying — but that “their food is good.” The concluding moral is almost flip: “Eat Hui food; there is no need to listen to Hui words.”

Checking Out Xian

Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: ““When the train docks, I emerge from the metal cocoon into another hangar, swooping and skylit. Outside, Xian is at once grander and more prosaic than its distant ancestor, a grid of choked streets traversed by a population verging on 10 million. It takes an hour to drive 10 miles into the oldest part of the city, a rectangle marked off by a moat and defensive walls 40 feet tall and 45 feet wide, which today are popular as an exercise circuit. (Facebook’s C.E.O., Mark Zuckerberg, once posted photographs of himself jogging along the cobbled ramparts.) [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“When the taxi driver can’t find the right alley, I continue on foot to my hotel, a converted house equipped with chic furniture and questionable plumbing, where a few days later the electricity will fail and the young staff, who have been busy icing cookies for Halloween — a holiday with roots among the Celts of Ireland two millenniums ago, as foreign to this country as Christmas — will scrounge up tiny Mickey Mouse-shaped candles for guests to light the way.

“At night, I walk alone, down pitch-dark lanes that yield to pedestrian malls and broad boulevards, tracking the icon of myself on my phone’s maps app, one of the few unhindered by China’s formidable firewalls. It works everywhere, even underground, in the sea of life churning through the circular underpass below the 14th-century Bell Tower — a former military alert system turned tourist attraction, lit up in red and green LED. Skyscrapers are restricted in this part of town, but there are KFC franchises and fake Apple stores that look like the real thing: minimalist white boxes with products posed like relics on maple altars.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “ My first night in the city, I wandered through the districts near Wenhua (Culture) Alley. Every building was concrete, but salvaged stone fragments heaped outside shop fronts recalled a more elegant past: white bas-relief panels carved with blossoms, deer and flaming pearls of wisdom; seal script characters chiseled into scattered blocks; and guardian lion sculptures, some so eroded that they had no eyes. A boy on a Segway floated past me, its wheels glowing an intense blue. I tasted ashy grit in the air. An old man from the Hui Muslim community was exercising on a metal cross-trainer: Public gym equipment filled a small park. Outside a market nearby, a sign warned, in Chinese and English: “Warm Prompt: You Have Been Into Video Surveillance Area.” Everywhere cameras tracked people moving through streets and rooms and markets, eating, talking, shopping, crossing streets, scrolling through smartphones. [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“I thought of “The Tower of Myriad Mirrors,” a 1640 novel by Tung Yueh, who later became a Buddhist monk and Chan (Zen) master, translated in 2000 by Shuen-fu Lin and Larry J. Schulz: “The four walls were made of precious mirrors placed one above another. In all there must have been a million mirrors.” The main character, Monkey, becomes disoriented. An old friend appears and explains: “Each blade of grass, each tree, everything moving and still, is contained here.”“

Food in Xian

Xian cuisine is well known throughout China. Visitors must try the local snacks and street food. Due to Xian's geographical location in the center of China, its cuisine has influenced from north and south China as well as east and west. . Local cooking features frying, sauting, braising and frequent use of salt, vinegar, capsicum and garlic. Among the great variety of local snacks, Yang Rou Pao Mo (crumbled unleavened bread soaked in mutton stew), Rou Jia Mo (Shaanxi Sandwich), and Cold Rice Noodles are the most popular.

A renowned place to try local snacks is the Muslim Quarter beside the Drum Tower. Ligaya Mishan wrote in the New York Times: ““I have come to Xian, like many before me, to eat yangrou paomo in the old town’s Muslim Quarter. At Lao Liu Jia Paomo, a clattering, no-nonsense canteen, the meal begins with an empty bowl and a pale round of flatbread, steamed and crisped until it’s hard on the outside but still spongy within. All customers are enlisted as prep cooks: Before we can eat, we must tear the bread into a hundred tiny pieces to fill that bowl. The ideal size for each piece, I’m told, is that of a soybean — otherwise “they judge you,” says Hu Ruixi, who with her American-born husband, Brian Bergey, runs the Xian-based food-tour company Lost Plate. She sits across from me, wrists flicking in practiced gestures as she reduces the bread to rubble. The same task takes me longer, my fingers fumbling as I try to get the pieces small enough, twisting and pinching, and I imagine the chefs sneering at my scraps. [Source: Ligaya Mishan, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“I end up with a coarse confetti that looks like popcorn dregs, which I return to the kitchen with a paper ticket dropped on top so the servers can remember whom it came from. Soon the bowl is thunked back down on the table, the bread now submerged — mo meaning “bread” and pao “soak” — in a fennel-laced broth of lamb bones simmered for half a day, with fatty cuts of yangrou (lamb) on top. There’s a side saucer of pickled garlic cloves, sharply sweet, to suck on as a respite from the lushness. The painstaking demolition makes sense: The smaller the nubs of bread, the better they absorb the soup. The drenched crumbs suggest a proto-noodle, as if knots of raw dough had been dropped directly into the broth to boil and set. It’s life-affirming; I can feel a plush new layer forming under my skin, protecting me from winter.

“Yangrou paomo belongs wholly to China’s north. Lamb is a legacy of nomadic herding on the Eurasian Steppe that reaches from Mongolia to Hungary; Hu admits she isn’t fond of the meat, having grown up in the south, in neighboring Sichuan Province.The presence of bread, too, attests to a geographical rift, marked by the Qinling Mountains just outside of Xian, which run through the heart of the country from east to west, separating the cool north from the warm and humid south, the wheat fields from the rice paddies.

“On a bright and chilly Sunday morning, the main street of the quarter is thronged by tourists, mostly Chinese, clutching skewers like neutered swords. Every other storefront seems to sell them, meat of all kinds (except pork) impaled and charred, even whole baby squid, which Hu, my guide, warns against: “Are we anywhere near the ocean?” Instead, we head for narrower alleys. In one shop, a young man yanks belts of dough back and forth, snapping them down on the steel counter with a biang biang, a sound so singular that the convoluted Chinese character for it — which doubles as the name of the resulting noodles, heaped with garlic and chile, and then glossed with hot oil and vinegar — doesn’t even appear in modern dictionaries. It’s a swirl of sub-characters, among them those for “moon,” “heart,” “speak,” “cave” and “horse,” requiring more than 50 strokes; cruel teachers have been known to assign the writing of it as a punishment for tardy students.

“Down another lane, Jia Wu Youhuxian is mobbed, but by locals. Jia Yu Sheng, the 73-year-old owner, has been making the house specialty since he was 16: thick pancakes with shining layers as translucent as vellum, brimming with beef and spring onions. Now, he keeps vigil over his sons, Jia Yun Feng and Jia Yun Bo, as they pull the dough into kerchief-thin panels that stretch but do not break. Half of each panel is heaped with meat and gilded with sauce, then rolled into a rough ball, while the other half is left long and stretched further still, into a rippling ribbon, and then it, too, is furled and the ball is pressed flat and fried into a great gold coin. The layers multiply, flaking, perfumed with fennel and its faint smack of menthol, another gift of the Silk Road.

“At Lao Liu Kaorou, Liu Xin Xian and his wife, Li Sai Xian, now in their 60s, have been selling beef skewers since 1987, out of what is essentially their living room. (They sleep upstairs.) The meat is dusted with salt, cumin and pulverized chile, but the secret, as with all barbecue, lies in the sauce, about which they will reveal nothing. Outdoor charcoal grills were recently banned as part of a government effort to ease pollution, and Liu feared that going electric would ruin the flavor of the meat; fortunately, the skewers, turned over a long trough of glowing red bars that resemble a xylophone, still come out blackened and smoky, and, as his wife points out, “it’s better for the environment.” With retirement looming, they can only hope that their son — who borrowed their recipe for his own barbecue spot, which he runs with a friend a few blocks away — will keep the tradition alive.

Shopping in Xian

The Xiao Zhai Commercial Center, situated in the area surrounding Xiaozhai Crossing, is popular with students and young people. Giant Wild Goose Pagoda Shopping District and the Muslim Quarter are popular with tourists. Xi’an Bell and Drum Tower Commercial Center located in the city center, is the most popular and largest commercial center in Xi’an. There are more than a dozen shopping malls as well as large supermarkets, amusement centers, cultural plazas and restaurants. It is spread among four main streets: Century Ginwa Shopping Center (under the Bell and Drum Towers Square) covers a total area of more than 30,000 square meters in its two underground floors and gathers together many of famous domestic and foreign brands..

Wenbaozhai Store and Cloisonne Artwork Store are two souvenir stores located on Yanta Road. Wenbaozhai Store specialises in reproductions of the terracotta warriors and horses of the Qin Dynasty (221-207 B.C.), eave tiles of the Qin and Han (206 B.C.-220 A.D.) dynasties, tri-color glazed pottery in the style of the Tang Dynasty (618-906), and rubbings from stone inscriptions, plus famous paintings and calligraphy works, reproductions of ancient paintings, hand-scrolling volumes, the four treasures of the study, metal and stone seal cutting, industrial fine-art painted sculptures, and filmstrips. The Cloisonne Artwork Store mainly deals with cloisonne artworks and golden headgear. They both adopt the classical mode of having the store in front and the workshop in the rear. Tourists can not only busy souvenirs here but also view the process of their production.

East Street is the most famous shopping street in Xian. The Kai Yuan Shopping Mall, Minsheng Department Store and Friendship Store are found here. Luomashi Pedestrian Street, with two large underground markets packed with all kinds of stores, is also in East Street. West Street features Tang Dynasty architecture and century-old shops such as Demaogong Crystal Cakes and Defachang Dumpling Banquet as well as big department stores such as including Yintai and Parkson stand along West Street.

Transportation in Xian

Many people in X'an uses the city's 270 bus routes serviced by over 7,800 buses, with an average system-wide ridership of over 4 million people per day. Taxis in Xi'an are predominantly BYD Auto made in Xi'an. Most, if not all, taxis in Xi'an run on compressed natural gas. For the taxis' fare, during the period of 6:00am through 11:00pm ¥9 for two kilometers for the fare fall and ¥2.3 for each additional kilometer. At night ¥10 for the fare fall and ¥2.7/km later.

There are six passenger transport railway stations in Xi'an. Xian Railway Station, traditionally the main train station for the city, is just north of the walled city. The new Xi'an North railway station, the station for the fast trains, is situated a few kilometers to the north. Xian is 1,000 kilometers from Beijing and 1,400 kilometers from west of Shanghai). The fast train between Xian and Shanghai takes about six hours. About a dozen and half train run between Xia and Beijing everyday each way. That trip takes as little as 4.5 hours.

Xian Metro opened in 2011 and has five lines with 161.8 kilometers of track and 107 stations (as of 2019). The Airport Intercity Railway opened in 2019. Eight lines are planned to be finished around 2021. It will mainly service the urban and suburban districts of Xi'an municipality and part of nearby Xianyang City. The subway system covers some of the most famous attractions, such as Banpo Museum (Banpo Station, Line 1), Bell and Drum Tower (Line 2), Fortifications of Xi'an (Line 2), the Giant Wild Goose Pagoda (Line 3 and Line 4), the Daminggong National Heritage Park (Line 4) and Shaanxi History Museum (Line 2, 3 and 4). Metro service generally operates between 6:00and 11:30pm. Xian Subway Map: Urban Rail urbanrail.net

The Xian Metro lines are: Line 1 runs from Fenghesenlingongyuan (Qindu, Xianyang) to Fangzhicheng (Baqiao). Opened in 2013 and expanded in 2019, it has 31.5 kilometers of track and 23 stations.

Line 2 runs from Beikezhan (Weiyang) to Weiqunan (Chang'an). Opened in 2011 and expanded in 2014, it has 26.7 kilometers of track and 21 stations.

Line 3 runs from Yuhuazhai (Yanta) to Baoshuiqu (Baqiao). Opened in 2016, it has 39 kilometers of track and 26 stations.

Line 4 runs from Beikezhan (Beiguangchang) (Weiyang) to Hangtian Xincheng (Chang'an). Opened in 2018, it has 35.2 kilometers of track and 28 stations.

Airport Line runs from Beikezhan (Beiguangchang) (Weiyang)to Airport West (T1, T2, T3) (Weicheng, Xianyang). Opened in 2019, it has 29.3 kilometers of track and 9 stations.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Perrochon photo site; Beifan.com; University of Washington; Ohio State University; UNESCO; Wikipedia; Julie Chao photo site

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2020