GANSU PROVINCE

Gansu GANSU PROVINCE is an arid, inhospitable province between Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang. Regarded as a sort of Chinese version of Siberia, because political prisoners have often been sent here, it is largely a barren desert with a few camels and little vegetation and little water. The Chinese, Hui, Tibetans, and Muslim minorities that have traditionally lived here often made their homes around oases and fertile valleys with sheep, orchards and mud-brick villages.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “ Gansu has largely been spared the overdevelopment that blights the country’s richer districts. Roughly the size of California, Gansu arcs from Mongolia at its northernmost point down to Sichuan Province in the south. The geographical center of China is near the city of Lanzhou, in the province’s southeast, while to the far west it borders the Xinjiang region, a place that under the Tang marked the extreme frontier.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

The travel write Theroux described Gansu as "a carefully constructed Chinese landscape of mud mountains sculpted in terraces which held overgrown lawns of ripe rice. The only flat fields were far below, at the bottom of the valleys. The rest had been made by people, a whole countryside that had been together by hand — stone walls shoring up the terraces on hillsides, paths and steps cut everywhere, sluices, drains and carved-out furrows." The cuisine of Gansu is based on the staple crops grown there: wheat, barley, millet, beans, and sweet potatoes. Within China, Gansu is known for its lamian (pulled noodles) and Muslim restaurants.

Gansu Province covers 453,700 square kilometers (175,200 square miles)and has a population density of 52 people per square kilometer. According to the 2020 Chinese census the population was around 25 million, about a million less than 2010. About 73 percent of the population lives in rural areas. Lanzhou is the capital and largest city, with about 3 million people. It is located in the southeast part of the province.

The population of Gansu was 25,019,831 in 2020; 25,575,254 in 2010; 25,124,282 in 2000; 22,371,141 in 1990; 19,569,261 in 1982; 12,630,569 in 1964; 12,928,102 in 1954; 7,091,000 in 1947; 6,716,000 in 1936-37; 6,281,000 in 1928; 4,990,000 in 1912. [Source: Wikipedia, China Census]

Han Chinese make up about 92 percent of the population of Gansu but there are significant numbers of Hui, Tibetans, Dongxiang, Tu, Yugur, Bonan, Mongolian, Salar, and Kazakh minorities. Gansu and Shaanxi are the historical home of the dialect of the Dungans — Hui who migrated to Central Asia. The southwestern corner of Gansu has a fairly large ethnic Tibetan population. Hui numbers increased after Hui in Shaanxi were resettled in Gansu after the Dungan Revolt (1862-1877).

Located in the up river part of the Yellow River, Gansu Province was once an important part of the Silk Road. The heart of Gansu is the Hexi Corridor, a 1,000-kilometer-long narrow strip of land on the western bank of the Yellow River that provides access between the Central Plans of China to the west and was a key part of the Silk Road. The province’s main tourist attractions — namely Dunhuang and Mogao Caves — are associated with the Silk Road. Gansu relies heavily on tourism for revenues. According to some estimates, one third of the province's revenues come from tourist receipts.

Despite this and being fairly rich in mineral resources, Gansu is the poorest province in China. The average income of farmers there in the early 2000s was around US$350 dollars a year, with farmers in some mountainous areas earning only US$200 a year. The per capita GDP in 2019 was US$4,783, the lowest in China Some of the poorest areas were hit hard by an earthquake in 2008, increasing the hardship of people already living on the edge. Some dubbed it the “forgotten disaster area." Desertification is serious problem in Gansu. In an attempt to bring trees to the barren hills in the central part of Gansu, water catchments call "fish scale pits" have been dug to capture rainwater to nourish planted saplings.

Tourist Office: Gansu Tourism Administration, 361 Tianshui Rd, 730000 Langzhou, Gansu, China, Tel. (0)-931-841-6638 and 6386, fax: (0)-931-841-8443; Maps of Gansu: chinamaps.org

See Separate Articles: SILK ROAD SITES IN GANSU factsanddetails.com ; DUNHUANG: SAND DUNES, SILK ROAD SITES, YARDANGS AND MOGAO CAVES factsanddetails.com ; MOGAO CAVES: ITS HISTORY AND CAVE ART factsanddetails.com ; GOBI DESERT SIGHTS IN INNER MONGOLIA AND GANSU IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Geography and Climate of Gansu

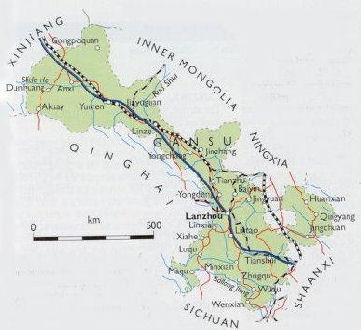

Gansu map Gansu is a landlocked province lying between the Tibetan, the Plateau and Huangtu plateaus, and borders Mongolia, Inner Mongolia, and Ningxia to the north, Xinjiang and Qinghai to the west, Sichuan to the south, and Shaanxi to the east.The Yellow River passes through the southern part of the province. The province contains the geographical centre of China, marked by the Center of the Country Monument at 35°50 40.9"N 103°27 7.5"E. The nearest sea is very far away.

The landscape in Gansu is very mountainous in the south and flat in the north. The mountains in the south are part of the Qilian Mountains, which contains the province's highest point, at 5,547 meters (18,199 feet). The vast majority of Gansu is on land more than 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) above sea level. Part of the Gobi Desert is located in Gansu, as well as small parts of the Badain Jaran Desert and Tengger Desert. A natural land passage known as the Hexi Corridor, stretching some 1,000 kilometers (620 miles) from Lanzhou to the Jade Gate, is situated within the province. It is bound from north by the Gobi Desert and Qilian Mountains from the south. Also known as the Gansu Corridor, it lies west of the great bend in the Yellow River (Huang He) and was traditionally an important communications link with Central Asia.

North of the 3,300-kilometer-long Great Wall, between Gansu Province on the west and the Greater Hinggan Range on the east, lies the Nei Monggol Plateau, at an average elevation of 1,000 meters above sea level. The Yin Shan, a system of mountains with average elevations of 1,400 meters, extends east-west through the center of this vast desert steppe peneplain. To the south is the largest loess plateau in the world, covering 600,000 square kilometers in Shaanxi Province, parts of Gansu and Shanxi provinces, and some of Ningxia-Hui Autonomous Region. Loess is a yellowish soil blown in from the Nei Monggol deserts. The loose, loamy material travels easily in the wind, and through the centuries it has veneered the plateau and choked the Huang He with silt. The Yellow River gets most of its water from Gansu and flows straight through Lanzhou, Gansu’s capital and largest city. The area around Wuwei is part of Shiyang River Basin.

Gansu generally has a semi-arid to arid, continental climate, with warm to hot summers and cold to very cold winters. Most of the precipitation arrived in the summer months. However, due to its extreme altitude and continental location, some areas of Gansu have a subarctic climate-with winter temperatures dropping to -40 degrees C and F.

See Separate Articles GOBI DESERT factsanddetails.com ; Shaanxi Loess Region, See Separate Article LAND AND GEOGRAPHY OF CHINA factsanddetails.com

Hexi Corridor

The heart of Gansu Province is the Hexi Corridor, a 1,000-kilometer-long narrow strip of land on the western bank of the Yellow River that provides access between the Central Plans of China to the west and was a key part of the Silk Road.

Hexi Corridor connects China with Central Asia runs along the "neck" of Gansu province. The Han dynasty extended the Great Wall across this corridor, building the strategic Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass, near Dunhuang) and Yangguan fort towns along it. Remains of the wall and the towns can be seen there. The Ming dynasty built the Jiayuguan outpost in Gansu. Nomadic tribes, including the Yuezhi and Wusun, lived to the west of Yumenguan and the Qilian Mountains at the northwestern end of Gansu and occasionally played into a part imperial Chinese geopolitics.

Hexi Corridor stretches from Lanzhou to the Jade Gate and is bound from north by the Gobi Desert and Qilian Mountains from the south. Dunhuang sits at the controlling entrance to the narrow Hexi Corridor, which led straight to the heart of the north Chinese plains and the ancient capitals of Chang'an (Xi'an) and Luoyang. The ruins of a huge Han Dynasty (202 BC - 220 AD) watchtower made of rammed earth seen today Zhangye Danxia (500 kilometers northwest of Lanzhou) is located in the middle of the Hexi Corridor in Zhangye city. Zhangye Danxia landforms features magnificent scenery with rocks of peculiar shapes and bright colors. It is arguably the best example an arid Danxia landscape.

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “For more than 2,000 years, a branch of the Silk Road — the 600-mile-long Hexi Corridor — has angled southeast from the Taklamakan and Gobi deserts to the Yellow River loess plains. The Hexi is hemmed in by deserts to the north and west, and by the great Qilian mountain range to its south. It is about 10 miles wide at its narrowest point, with oasis towns every 50 to 100 miles. For most of the Han dynasty, which lasted roughly from 206 B.C. to A.D. 220, no soldier, pilgrim, explorer or trader could enter northwestern China without first passing through the corridor, which was vigorously guarded. In A.D. 123, the imperial secretary Chen Zhong, in a strategic memo to the emperor, translated in 2009 by John E. Hill, wrote that if the Western Regions were not defended, “the wealth of the [nomadic Xiongnu tribes] will increase; their audacity and strength will be multiplied,” and the four garrisons along the Hexi Corridor would be endangered. “We will have to rescue them,” he continued. The great cities of China’s central plain, including the capital, would then be left vulnerable to attacks.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

Zhangye Danxia

History of Gansu

Gansu's name was first used during the Song dynasty and is a combination of the names of two Sui-Tang dynasty prefectures: Gan (around Zhangye) and Su (around Jiuquan). The eastern part of Gansu is regarded as part of one of the cradles of ancient Chinese civilisation. The Neolithic Dadiwan culture flourished in the eastern end of Gansu from about 6000 B.C. to 3000 B.C. and the Majiayao culture (3100- 2700 B.C.) and part of the Qijia culture (2400-1900 B.C.) originated in Gansu, The Yuezhi originally lived in the very western part of Gansu until they were forced to emigrate by the Xiongnu around 177 B.C. [Source: Wikipedia]

The State of Qin, known in China as the founding state of the Chinese empire, grew out the Tianshui area of southeastern Gansu. The Qin name is believed to have originated, in part, from the area. Qin tombs and artifacts have been excavated from Fangmatan near Tianshui. A 2200-year-old map of Guixian County was found here.

In imperial times, Gansu was an important strategic outpost and communications link for the Chinese empire.The 1000-kilometer-long Hexi Corridor — which links the Chinese plains with the far west areas of China and Central Asia — runs along the "neck" of the province.The Han dynasty extended the Great Wall across this corridor, building the strategic Yumenguan (Jade Gate Pass, near Dunhuang) and Yangguan fort towns along it. Remains of the wall and the towns can be seen there. The Ming dynasty built the Jiayuguan outpost in Gansu. Nomadic tribes, including the Yuezhi and Wusun, lived to the west of Yumenguan and the Qilian Mountains at the northwestern end of Gansu and occasionally played into a part imperial Chinese geopolitics.

As part of the Qingshui treaty (823) between the Tibetan Empire and the Tang dynasty, China lost much of western Gansu province for a significant period. From A.D. 848 to 1036, it was the home of the Buddhist Yugur (Uyghur) state called Ganzhou Uyghur Kingdom established by migrating Uyghurs after the fall of the Muslim Uyghur Khaganate. During the Silk-Road-era, Gansu was an economically important province and a cultural transmission route. Temples and Buddhist grottoes such Mogao Caves and Maijishan Caves contain artistically and historically revealing murals. An early form of paper inscribed with Chinese characters and dating to about 8 BC was discovered at the site of a Western Han garrison near the Yumen pass in August 2006.

The Western Xia Dynasty (1038-1227) controlled much of Gansu as well as Ningxia. Gansu was a center of the Dungan Revolt of 1862–77 began. Among the Qing forces were Muslim generals, including Ma Zhan'ao and Ma Anliang, who helped the Qing defeat rebel Muslims. There was another Dungan revolt from 1895 to 1896.

As a result of frequent earthquakes, droughts, famines and its remote, peripheral location, economic progress has been much slower in Gansu than other provinces of China until recently. A 8.6-magnitude earthquake in Gansu and Ningxia in 1920 killed around 180,000 people mostly in Ningxia. A 7.6 magnitude in 1932 killed 275. Muslim warlords controlled Gansu in the early to mid 20th century. Gansu was a passageway for Soviet supplies to Mao Zedong’s Communists during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945). The Kuomintang Islamic insurgency in China (1950–1958) was a prolongation of the Chinese Civil War in several provinces including Gansu.

Lanzhou

Lanzhou on a clear day

Lanzhou (1,560 kilometers west-southwest of Beijing in the southeast part of Gansu) is the capital and largest city of Gansu Province, with about 3 million people. It is the largest city on the Yellow River and one of the most polluted cities in China if not the world. In the old days it was regarded as one of the gateways to the Silk Road, the last major place to change money and buy provisions before heading to Turkestan and Central Asia.

Today Lanzhou is a dirty, industrial city filled with smoke and air-borne chemicals from petrochemical factories and brickyard kilns trapped inside a long, narrow Yellow River valley, flanked by mountains. The air pollution is so bad there has some discussion about blasting a hole in the mountains to allow the dirty air to escape. Lanzhou was described The New Yorker as “an assemblage of rusting machinery, slag heaps, and landfills; of chimneys, brick kilns, and belching thick smoke; of concrete tenements whose broken windows are held together with cellophane and old newspapers."

Despite this the China Urban Competitiveness Ranking released by the China Institute of City Competitiveness (CICC) listed Lanzhou as one of the Top Ten Chinese cities with best landscapes ib 2011. It has mountains to the south and north, and the Yellow River flows east to west through it. Famous attractions around the city include the Yellow River, Baita Mountain, Bapan Valley, Tulugou Forest Park, Wuquan Mountain Park, Xinglong Mountain and Zhongshan Bridge,

Lanzhou Metro opened in 2019. Line 1 runs from Chenguanying (Xigu) to Donggang (Chengguan) and has 25.9 kilometers of underground track and 20 stations. Line 2 will runs from Yanbei Road to Dongfanghong Square. Expected to open in 2022, it will have nine kilometers of track and nine stations. Lanzhou Subway Map: Urban Rail urbanrail.net

Tourist Office : Lanzhou Tourism Administration, 14-1 West Xijin Rd, 730050 Langzhou, Gansu, China, tel. (0)-931-233-9473, fax: (0)- 931-233-1902 Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide ; Maps of Lanzhou: chinamaps.org ; Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books; Admission: Zhongshan Bridge: free; Baita Mountain: 6 yuan; Xinglong Mountain: 38 yuan; Wuquan Mountain Park: 6 yuan; Tulugou Forest Park: 50 yuan. Getting There: Lanzhou is accessible by air and bus and lies on the main east-west train line between Beijing and Urumqi. Two fast trains and seven normal ones operate between the Beijing and Lanzhou each way each day. The fast ones take 8.5 to 9.5 hours and the slower ones take 16 to 28.5 hours. Traveling by air is the quickest way to get there and not that much more expensive. Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

Air Pollution in Lanzhou

Lanzhou on a usual day Lanzhou is now listed as 158th worst city in the world — and around the 100th worst in China — in terms of air pollution in a 2018 World Health Organization survey. This is much better than jus a few years earlier. According to Asian Development Bank in January 2013, it was one one of the most air polluted cities in the world. A study by the Washington-based World Resources Institute in the late 1990s reported that nine of the ten cities with the world's worst air pollution were in China. At the top of the list was Lanzhou.

The amount of suspended particles in Lanzhou in the 2000s was twice that of Beijing and 10 times that of Los Angeles. Simply breathing was said to be equivalent to smoking two packs of cigarettes a day. The pollution was often so bad that people could feel the grit in their noises and between their teeth and routinely developed sore throats, headaches and sinus problems. When children were asked what color the sky was, they often replied: "White, sometimes yellow."

The pollution is caused by coal smoke, car exhaust, pollutants released by petrochemical, metal and heavy industry factories and dust blown from the arid yellow mountains that surround the city. The factories in Lanzhou were placed there in accordance with a plan by Mao to locate heavy industry factories in western China where he thought they would less vulnerable to nuclear attack. The pollution is especially bad because atmospheric conditions create layers of dense air that trap the pollutants and Lanzhou is located in valley surrounded by mountains that prevent winds from blowing the pollutants away. Shutting down some state-owned factories has helped reduce some of the air pollution there.

Officials in Lanzhou considered a plan to blast a "hole" in a nearby mountain to allow smog to escape from the valley that entraps it. One local environmentalist told Newsweek, "It's like a person is smoking in a house with all the doors closed. If we open a door, fresh air can blow in." The "hole" would have been produced by widening a narrow pass to two kilometers by blasting away sandy loess ridges with high-pressure hoses. Nobody knows if the plan would have worked. As outrageous as this scheme seems there are few other alternatives. Replacing or improving the Soviet-designed factories would will cost billions of dollars. A hole was never blasted but the top of a mountain was blown off. It ended up adding to the pollution problem not solving it. Even though elaborate sprinkler system was brought in to control dust, large amounts of polluting particles were hurled into the air by explosives and they contributed to particulate pollution.

Sights in Lanzhou

Sights in Lanzhou including Zhongshan Bridge, the first permanent bridge over the Yellow River; the Lanzhou Botanical Garden (Anning District), with a large variety of trees, flowers and other plants; Xiguan Mosque, one of the larger mosques in China; Wuquan Mountain, with many ancient architectural sites; Xinglong Mountain, with thick pine forests and colorful temples; and Lutusi ancient government, a large complex of ancient governmental buildings. Five Spring Mountain Park (on the northern side of Gaolan Mountain) is famous for its five springs and several Buddhist temples. Baita Mountain Park was built close to the mountains at an elevation of 1,700 meters 5,600 ft and opened in 1958 across Zhongshan Bridge.

The Gansu Provincial Museum displays archaeological and fossil finds from Gansu and has exhibitions on Gansu's history. Lanzhou Museum, is an important cultural repository for Silk Road artifacts, with more than 13,000 pieces including pottery, porcelain, bronze, calligraphy, coins, jade and stoneware. It contains 52 national first-class cultural relics, national second-level cultural relics and 682 national third-level cultural relics.

Lanzhou Painted Pottery Museum has collection of 250 pieces, including 50 precious cultural relics. Its primary focus is painted pottery of the Majiayao civilization. Gansu Science and Technology Museum is geared towards teaching children about sound, light, electricity and other scientific principals with hands-on and high-tech displays. Gansu Art Museum provides local and outside artists with a platform to display their work. The Lanzhou City Planning Exhibition Hall shows the impact of the Yellow River culture of Lanzhou and has urban and architectural exhibitions.

Near Lanzhou

Linxia (70 kilometers southwest of Lanzhou) in Gansu is a small city and legendary trading center known as China’s Mecca. It is a center of religious life for the Hui and grown in recent years due to the drug trade. Occupied primarily by Muslim Huis, it is filled with dozens of new mosques and a lively market where you can purchase coral beads from Taiwan, animal pelts from Tibet, carpets from Turkmenistan and. if the right connections, heroin from Yunnan and hashish from Xinjiang.

Linxia is a dry and remote but also alive with religious life. Matthew S. Erie, an expert on Muslims in China, told the New York Times: “The region from Lanzhou to Linxia is often called the Quran belt. When you’re on the highway, it’s impossible to go a minute without seeing a new mosque under construction. “It’s the base of Islam in the northwest. Muslims have built mosques and prayed there since at least the 14th century. Some say certain Muslim tombs there date to the Tang dynasty. That’s hard to prove, but it shows how important it is. It’s a place where Islam took hold.” [Source: Ian Johnson New York Times, September 6, 2016].

Jinchang (200 kilometers north-northwest of Lanzhou) is the place supposedly inhabited by Roman legionaries who fled to ancient China in 53 B.C. There are Roman-themed hotels and restaurants. There is some discussion of erecting a mini-coliseum. Web Site: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide

Spring of Snakes (near the village of Recoako in Gansu on the Kangba Plateau) is a warm water spring popular with people and snakes. The snakes live in adjacent cave and slither out to swim with people bathing in the spring. Also found in this area are basketball-size balls of worms and Himalayan snow pigs (marmots). I wrote about this place a while ago and can’t find it now via Google but it certainly sounds interesting if it exists.

Tianshui

Tianshui (250 kilometers southeast of of Lanzhou) is the second-largest city in Gansu Province, with a population of about 3.5 million people. Situated in southeastern Gansu province, in north-central China. It was historically an important place along the Silk Road, the great route westward from Chang'an (present-day Xian, in Shaanxi province) to Central Asia and Europe. Tianshui Tram Map: Urban Rail urbanrail.net

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: Tianshui is “a city with roots in the Neolithic era, near one of the oldest archaeological sites in northwestern China, where remains dating back to 5000 B.C. have been discovered. The bullet train took a little under two hours to go about 200 miles. I passed scarps and junkyards glinting with shattered plastics and glass, graveyards on hills, a giant iron woman cradling a gilded sheaf. There were dry riverbeds and golden poplars, pomegranate trees and pylons. On the hills, radio towers; smoke from distant fires floated over the terraced fields. [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“I arrived in Tianshui an hour before sunset. Here was a city of flyover walkways and half-built skyscrapers that ran mile after bleak mile along the dirty waters of the Jie River. Tianshui was once surrounded by high gateways and spectacular city walls, whose lines followed the river. Modern Tianshui has lost those walls: Only the very oldest residents remember they once existed. As evening fell, I explored Nanguo Temple in the southern hills above Tianshui. The mountain air was clear and very cold. Over the doorways to their bedrooms and kitchen, the Buddhist monks had tacked up calligraphy written on thick paper, enigmatic jokes and prayers. One read: “At night there is no place to stay.”

“In A.D. 759, the poet Du Fu took refuge in the area after resigning from his government post near Chang’an. Du Fu, translated here by Stephen Owen, excelled in describing the human cost of the Tang dynasty’s imperial ambitions, the suffering of individual soldiers who protected the Silk Road and defended the country’s distant borders: “Already gone far from the moon of Han, / when shall we return from building the Wall? Drifting clouds journey on southward at dusk; / we can watch them, we cannot go along.”

Bingling Si

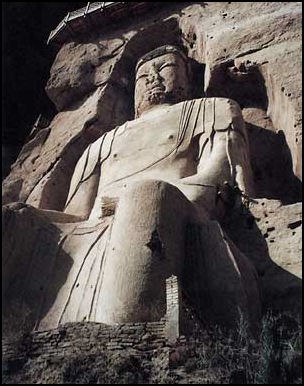

Bingling Si (near Tianshui) means "thousand Buddha" in Chinese and "10,000 Buddhas” in Tibetan. Situated in Xiaoji Mountain, 20 miles southwest of Yongjing County, it is where people have been carving statues and niches into two-kilometer stretch of steep cliffs above the surging Yellow River for more than 1000 years. There are 183 caves, 694 stone statues, 82 clay figures and 900 square meters of murals preserved here. The tallest statue is 27 meters (80 feet) high and the smallest is 20 centimeters.

Bingling Temple, or Bingling Grottoes, is situated in a canyon along the Yellow River. Two thirds of the sculptures which are set up along four tiers were made over 1000 years ago. The oldest date to 420 A.D. during the Western Jin Dynasty. The great 27-meter-high Maitreya Buddha is similar in style to the great Buddhas that once lined the cliffs of Bamiyan, Afghanistan. Access to the site is by boat from Yongjing in the summer or fall. There is no other access point.

Web Site and Getting There: Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

Maijishan Scenic Spots

Maijishan Scenic Spots (40 kilometers southeast of Tian shui, 330 kilometers southeast of Lanzhou) is a Buddhist cave area nominated to be a UNESCO World Heritage site in 2001. Maijishan is a 142-meter-high hill off the surrounding landscape. It got its name from its wheat pile shape. Maijishan means "Wheat Stack Hill". The site contains 194 caves, in which are preserved more than 7,200 sculptures made from terra cotta and murals covering over 1,200 square meters.

Maijishan grotto's history can be traced back 1,600 years ago. According to a report submitted to UNESCO: Maijishan Mountain is placed on the first list of state key scenic spots by its peculiar grottoes, exquisite clay sculptures luxuriant vegetation, all kinds geologies and landforms, mountain peaks. Its main area is 142 square kilometers including Maijishan Grottoes, the Immortal Cliff, the Stone Gate, Quxi Stream and Jieting Hot Spring. Maijishan Grottoes was first built in Later Qin (A.D. 384-417). Construction continued during 12 dynasties: West Qin, Northern Wei, West Wei, Northern Zhou, Sui, Tang, Five Dynasty, Song, Yuan, Ming and Qing. Although the site have endured earthquakes and fires, 194 caves, 7200 sculptures, 1000 square meters of fresco which are found and excavated a cliff that is 30 meters to 80 meters high from the ground. More than 70 percent caves were excavated in the North dynasty. There are many clay sculptures. Some are are well-shaped and excellent examples of art, with some best pieces produced during the early period. [Source: National Commission of the People's Republic of China.

Among the 194 grottoes and thousands of sculptures and preserved mural paintings, the eight cliff pavilions built by the Northern Dynasty have long been recognized as a "gallery of oriental sculptures". One traveler wrote in in CRI: The next morning we directly went to the Maijishan grottoes, which are one of the four biggest grottoes in China. Climbing the steep mountain step by step, we saw weathered but still gorgeous statues of Buddha and monks standing in different caves, delicate murals painted on the clay ceilings of the mountain and sculptures of animals which were carved as a form of worship. Besides, the picturesque scenery complements the grottoes. [Source: CRI, May 21, 2009]

Visiting Majishan

Anna Sherman wrote in the New York Times: “ “ Sited midway up sheer vertical cliffs, Maijishan was founded in the Later Qin dynasty (A.D. 384-417) as an isolated retreat where Buddhist monks from Chang’an might meditate. When I visited, the contrast between Tianshui and these ancient ruins — between industrial wasteland and classical landscape — was extreme. Maijishan was remote enough that its paintings and sculptures were spared during wars and revolutions, when other cultural relics were destroyed; they still record what the art historian Michael Sullivan in his 1969 history “The Cave Temples of Maichishan” described as “the metropolitan style of [the sometime capital] Luoyang in its brief glory.” Certain statues resemble the art of sites in Xinjiang; others are more closely related to styles found in India. In the third volume of her magisterial study “Early Buddhist Art of China and Central Asia” (2010), the scholar Marylin Martin Rhie traced links between Maijishan’s sculptures and the artworks of other Silk Road monastic centers. In some of the figures’ flowing drapery, and in the “delicacy of the linear outlines and contours of the features of the faces,” she found the influence of Greco-Buddhist artists from Gandhara, a region that once straddled the modern border between Afghanistan and Pakistan. In the waving hairstyles, Rhie found similarities to the sculptures of Tumshuk, a site near Kashgar. Connections between Maijishan and the ancient centers of what is now Xinjiang were particularly strong: Some bodhisattvas wore three-sided jewel crowns that also adorned paintings and a wooden statue at the Kizil Caves of Kucha, the ancient Buddhist kingdom north of the Taklamakan, while a distinctive pearl-band design also occurred in one of Kizil’s earliest caves. Near Maijishan were roads leading not just west through the Hexi Corridor and on to Central Asia but also south to Chengdu and east to Chang’an. Maijishan was secluded, Sullivan wrote, but “open to influences.” [Source: Anna Sherman, New York Times, May 11, 2020]

“The monastic community here was in a remote, wild place set among green mountains, bamboo groves and cornfields. Many frescoes have been exposed to the elements, and as a result, the paintings are poorly preserved. Buddhas are set into Maijishan’s cliff face; they resemble smaller versions of Afghanistan’s Bamiyan statues, which were destroyed by the Taliban in 2001. The sixth-century poet Yu Xin recorded how a military governor “had a path like a ladder to the clouds constructed on the southern face of the rock,” and commissioned a series of Buddha sculptures as a temple offering in his father’s memory: The cave — Scattered Flower Pavilion — still exists, although the entire front section was sheared away in A.D. 734 during an earthquake, a temblor that also divided Maijishan’s west side from its east. Other caves that Yu Xin described — the Moon Disc Palace and the Hall of Mirrored Flowers — may have disappeared altogether. But the surviving Buddhas and celestial beings carved into the mountain look out over a spectacular view that cannot have changed that much in the last thousand years. “For a hundred li,” Du Fu wrote, “you can make out the smallest thing.”

“Maijishan also contained some of China’s most beautiful sculptures. In the Cave of the Steles, a Buddha stretched his hand down toward a smaller figure who might be a young monk or — according to my local guide — the historical Buddha’s own son. Specialists are uncertain whether the two figures were created during the Tang dynasty or later, in the Northern Song period of A.D. 960 to 1127. Whatever its age, the Buddha had the most beautiful hands of any sculpture I had ever seen, and the space between the statues — the Buddha’s outstretched fingers, the crown of the boy’s head — was electric. Whether the two were greeting or leaving each other, I did not know; perhaps they did not belong together at all but had been brought here from separate caves. I crouched at the foot of the small statue, looking into its face. At the outer edge of another cave, a statue of a bodhisattva smiled slightly, her right palm raised in the gesture that means “don’t be afraid.” During the 734 earthquake, the mountain collapsed a few inches past her right shoulder; on the jagged wall behind her, where the cliff met the sky, I could see a flying apsara and the curve of a halo — all that remain of some greater whole. Beyond rolled a green line of mountains, the dark blue sky and, jarringly, a cluster of security cameras and loudspeakers. Far below the wooden walkways that linked painted cave to cave, the bells on a donkey’s harness sounded: Local touts had set up replica caravans for tourists to ride. Polo and his co-author, Rustichello da Pisa, wrote of the men traveling the Silk Road, here in Ronald Latham’s 1958 translation: “Round the necks of all their beasts they fasten little bells, so that by listening to the sound they may prevent them from straying off the path.”“

Xiahe

Xiahe (160 kilometers southwest of Lazhou and four hour drive from Lazhou) located in the southern part of Gansu in what has traditionally been part of the Tibetan province of Amdo. Located at 3,000 meters above sea level in a barren mountain valley, it is primarily a jumping off point for visits to Laprang Monastery, which is with walking distance. Festivals, horse races and religious ceremonies are held in the town and at the monastery.

Xiahe (pronounced shyah-huh) is a frontier town with separate Chinese, Tibet and Hui Muslim parts of town. It is filled with Buddhist monks, Hui Muslim traders, Tibetan pilgrims and Western backpackers. On the main street are a number interesting shops selling pilgrim gear such as silver dagger belts, bone carvings and jackets with brass bells. Some of the pilgrims are quite exotically dressed. Restaurants offer noodle dishes, Tibetan dumplings, Muslim lamb dishes and Chinese rice dishes. Many of the monks subsist on bread dipped in yak butter.

Between Lazhou and Xiahe there are numerous Hui villages, each with their own mosques. Some Hui mosques have rounded domes like Middle Eastern mosques. Others look more like pagodas, with green and white tiles and topped by crescent moons. As you get closer to Xiahe more Tibetan villages begin appearing. Many travelers visit the yak pastures at Sangke. Get there early before the tour buses arrive. There is also good hiking in nearby valleys and mountains. Web Sites: Travel China Guide Travel China Guide Budget Accommodation: Check Lonely Planet books. Getting There: Xiahe is only accessible by bus. Lonely Planet Lonely Planet

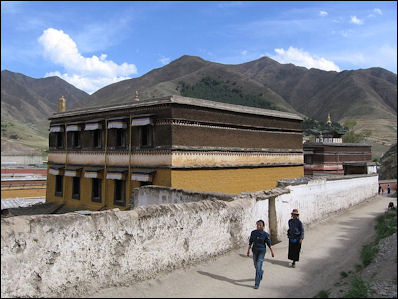

Labrang Monastery

Labrang Monastery (near Xiahe) is the largest and most important Tibetan Buddhist monastery outside of Tibet and the largest working monastery in Tibet and China. Built in 1709 by the living Buddha Jianuyang and situated 7,000 feet above level, this Yellow Hat religious complex is home to 2,000 monks, twice the number Beijing allows it to have, and embraces 35 temples, six academic institutes, several large temples, living Buddha residences, lama and monk quarters, 10,000 volumes of Tibetan classics and countless lesser scriptures and historic relics.

Labrang Tashikyil Monastery is located in Xiahe County, Gannan Tibetan Autonomous Prefecture It is one of the six major monasteries of the Gelukpa tradition of Tibetan Buddhism and is the most important one in Amdo. Built in 1710, it is headed by the Jamyang-zhaypa. It has 6 dratsang (colleges), and houses over sixty thousand religious texts and other works of literature as well as other cultural artifacts.

Labrang attracts pilgrims from all over China and is a kind of mother temple to smaller temples in Gansu and Qinghai provinces. Pilgrims walk on a two-mile path around various temple buildings, rotating the 1,174 prayer wheels along the way and kissing walls. Try to visit the monastery in the morning before the Chinese tour groups arrive.

Visitors are only allowed to enter the temples as part of a monk-led tours (English tours are available). Once inside you allowed to wander around on your own. In the morning you can see monks lined up with arching yellow hats blasting on trumpets in front of the colorfully-painted, gold-roof main prayer hall. Inside the temples are murals, and images of Buddhas, gods and demons illuminated by yak-butter lamps. There is a huge library with Hindu, Sanskrit and Tibetan scrolls and yak butter sculptures that manage to stay intact because of the cool climate.

The current abbot, the sixth incarnation of Jiamuyung, came to Labrang when he was four years old and has helped oversee the monastery's restoration. A decade ago much of the monastery was in ruins: destroyed during the Cultural Revolution and a fire in the 1980s.

Labrang Monastery has six institutes — the Institute of Esoteric Buddhism, Higher and Lower Institutes of Theology, Institute of Medicine, Institute of Astrology and Institute of Law. It once had 4,000 monks. It hosts the Great Prayer Festival around the time of the Tibetan New Year in February. The main events are the laying out of a 98-foot tank on the hillside near the town and Cham dances.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons, Nolls China Web site; CNTO; Zhangye Danxia, Explorersweb

Text Sources: CNTO (China National Tourist Organization), China.org, UNESCO, reports submitted to UNESCO, Wikipedia, Lonely Planet guides, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, National Geographic, China Daily, Xinhua, Global Times, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Bloomberg, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Compton's Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Updated in July 2021