BICYCLES IN CHINA

There are around a half a billion bicycles in China — about 1 bicycle per household — more than any other country but this was down from from 670 million in the 1990s. There are seven million registered bicycle riders in Beijing and 6.5 million in Shanghai. In most places bicycles outnumber cars at least 10 to 1.

There are around a half a billion bicycles in China — about 1 bicycle per household — more than any other country but this was down from from 670 million in the 1990s. There are seven million registered bicycle riders in Beijing and 6.5 million in Shanghai. In most places bicycles outnumber cars at least 10 to 1.

A Beijing New York Times reporter wrote: “Bicycles can be found on every street, and they come in an array of shapes, sizes and uses. There are bikes with cargo beds that carry everything from bags to trash to new sofa sets. There are electric bikes and miniature scooters. Children bounce on the luggage rack behind their parents, and older women teeter on even older bikes. No one wears a helmet.” It is not uncommon to see bicycles with caged songbirds dangling from the handlebars.

Around 20 million bicycles are sold in China for the domestic market. These days more Chinese-produced bicycles are sold for export. In China The sale of mountain bikes and multi-geared bikes is rising in China as sales of traditional clunkers is declining. Bicycles are increasingly being looked upon as recreation vehicles as well as means of commuting and running errands. While riding in a black Audi sedan, the Vice Mayor of Beijing, Wang Baosen, told the New York Times, "Riding a bike helps you exercise. It can also help save energy, it reduces pollution and it is very convenient for mass use."

Bicycles used to be the chief mode of transport in large cities and China was known as the "kingdom of bicycles". In Beijing in the early 2000s, there were an estimated eight million bicycles, accounting for 83.5 percent of the city's road traffic. Bicycle use in China has fallen as more Chinese have become car owners. In 1980, more than 60 percent of commuters rode bikes. By 2000, that number dropped to 38 percent. By 2014, fewer than 12 percent of Chinese commuters rode bicycles. According to a Beijing radio station sited in an Asia New Network article the number of people in Beijing that used bicycles for some of their transport needs fell from 60 percent in 1995 to 20 percent in 2010. It also reported that 40 percent of car owners in China use their cars to drive less than five kilometers, a distance that could easily be covered on a bicycle. The Communist Party aims to increase the number of bike riders back up to 18 percent by 2020.

Bicycles can be rented for one or two dollars a day in many places frequented by tourists. The old-style Chinese bicycles are heavy and have only one speed, but are fairly strong. Mountain bikes can be rented in some places but sometimes they are less strong than traditional bicycles. Make sure the seat is high enough and the bike is in good working order before setting off. If you get a flat tire or have trouble with the bike there are numerous roadside repair shops that will fix the problem for a small fee.

What to do with old, rusting bicycles is a big problem in many Chinese cities. Recycling centers are a rarity. Many people dispose of their bikes by abandoning them in fields, parking lots or alleys where they can remain for months.

Articles on TRANSPORTATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; Bike China Travelogues Bike China Travelogues

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Tian Tian Zhong Wen - Bicycle Kingdom” (English and Chinese Edition) by MacMillan Education Amazon.com; “Finding Compassion in China: A Bicycle Journey into The Countryside” by Cindie Cohagan Amazon.com; “Dad's Bicycle: Journey of A Chinese Family” by Helen Wang Amazon.com; “Handbook on Transport and Urban Transformation in China” by Chia-Lin Chen, Haixiao Pan, et al. Amazon.com; “English-Chinese and Chinese-English Glossary of Transportation Terms: Highways and Railroads” by Rongfang (Rachel) Liu and Eva Lerner-Lam Amazon.com Country Driving: A Journey Through China from Farm to Factory by Peter Hessler, Peter Berkrot, et al. Amazon.com; “Tibet Transportation” (1991) by Editors: Zhang Ying etc. Amazon.com; “Chinese Junks and Other Native Craft” by Ivon A. Donnelly and Gareth Powell Amazon.com; “The Great Ride of China: One Couple's Two-wheeled Adventure Around the Middle Kingdom” by Buck Perley Amazon.com;

History of Bicycles in China

Carrie Gracie of the BBC News wrote: “The arrival of the bicycle was initially greeted with scorn. To begin with, it was only so-called "foreign devils" who rode them. No self-respecting Chinese gentleman — and even less a woman — would be seen sweating under their own locomotion. But soon it would become the Chinese worker's vehicle of choice. The last emperor loved bicycles. He is said to have removed doorstops in the Forbidden City so that he could cycle around.” [Source: Carrie Gracie BBC News, October 9, 2012 ***]

In the Mao era bicycles were regarded as one of "three bigs" — along with a sewing machine and wristwatch. People placed their names on waiting lists for years to get them and took out loans form the factories where they worked to help pay for them. Chinese valued bikes in part because the public bus system was so bad and owning a car was impossible. Many cities had wide bike lanes, ample parking spaces on the sidewalks and bicycles had the right of way at intersections.

The first bicycles with air-filled rubber tire seen in China were ridden by two Americans, named Allen and Sachtleben, who ended a three-year bicycle journey from Istanbul to China in 1891 recorded in the book “Across Asia on a Bicycle”. Not long afterwards the child-emperor Puyi passed many hours in the Forbidden City riding around on a bicycle given to him by his Scottish tutor.

Commuting and Commerce by Bicycle in China

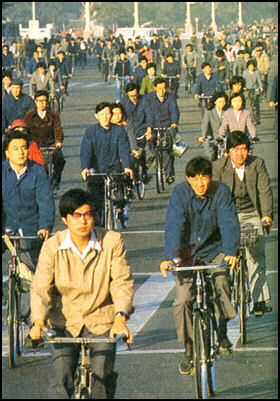

Bike commuters in the 1980s The Chinese ride their bicycles in the rain and snow. Up until fairly recently when it rained in Shanghai, the streets filled with bicycle riders in blue, yellow, red and purple ponchos. There were so many bicycles in Shanghai that sometimes traffic stammered to a halt with bicycle gridlock.

China has roads and reserved for bicycles. Roadside bicycle repairmen are common sights.

Each year there around 350 bicycle related fatalities in Shanghai. Chinese cyclist often ride against the flow of traffic, swerve suddenly and come flying in off of side roads without looking. Posters of cyclists horribly mutilated in accidents are hung up all over town. Cyclists who have survived several accidents are often sent to "re-education classes."

The Chinese perform modern day miracles with their bicycles and tricycles. National Geographic reporter Ross Terril witnessed a double bed with a floral mattress, boxes of hens piled eight feet high and tied together with string; and a purple velvet sofa and a wardrobe — all carried on the backs of bicycles and tricycles. Farmers take 100 kilogram pigs to slaughter on the back of tricycles.

These days, bicycle use is declining in many places as more and more people have access to cars. In 1998, bicycles were banned from East Xisi Street, near the Forbidden City in Beijing, to make it easier for car traffic. Violators were chased down by guards with bullhorns and red arm bands. The ban was extended to other streets later on. Many people were angered by the ban. Bicyclists were angry they had to take a longer route and environmentalists said it sent the wrong message at a time when Beijing has recording some of the world's worst air pollution. Bicycles were banned from all major roads in Shanghai in 2004 to make more room for cars.

One Beijing cyclist told the Washington Post, “The drivers are very aggressive. They won’t wait for you for a second. The road belongs to them now.” Some studies indicate that the decline of bike usage may be short-lived as the practicality of a bicycles kicks in and the novelty of car driving wears off.

Bicycle Riding in Beijing

CBS news reported: Early each morning Sun Jian prepares — or, well, braces — for his commute. The 39-year-old zig-zags through Beijing traffic on his 30-minute journey through this city of more than five and a half million cars. Twenty-eight thousand new cars came onto Beijing streets in 2015. "It's dangerous," Sun admitted. "Cars and bikes are fighting for space on the road, but what can you do? " [Source: cbsnews.com, March 15, 2016]

“Beijing bicyclists pedal differently from their Western counterparts,” Joost Polak wrote in the Washington Post. “They set their seats a bit low, lean almost backwards and pedal with the arch or even the heels rather than the ball of their feet, which plays their knees out on the upstroke.”

Explaining how his Chinese friend shifted across six lanes of traffic in Beijing Polak wrote in the Washington Post, “Xian Fang, moved ahead to the first lane of cross traffic...Seeing a gap, she pushed through to the next lane, braked to a near standstill, them pumped her way across another lane. After a couple more lanes I began to see the gaps that seemed so clear to her. And then it was time to look in the other direction and work our way across the traffic coming from our left.”

On bike lanes on both sides of the streets are filled with bikes, electric and gas-powered motorbikes, delivery tricycles and pedicabs traveling in both directions. Polak wrote,: “They are almost always wide enough for cars to fit into. So they do. Sometimes they nip into the bike lane because all of the vehicle lanes are slowing. Sometimes the drivers pull over and park to make a cell phone call.”

American Olympic cyclist Taylor Finney took his bike out for a spin on the streets of Beijing during the Olympics in 2008. He said he couldn’t believe that none of the Chinese were wearing helmets. “I wore a helmet because I’m scared of Chinese drivers!” he said. “I’m scared even on a bus. There’s no way I’m not wearing a helmet.”

Bike Lanes of Beijing

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Beijing has at least three definable species of bike lane. The most luxurious, which we’ll call Business Class, is a ribbon of designated asphalt set off from the car world by a sidewalk and often a tree or two: The second variety, Economy Class, shares the roadway with cars and buses, but takes up the prized area beside the curb, monopolizing the space for parking that has John concerned.” [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, March 11, 2011]

“The third species, which we’ll call Economy Plus, has elements of both: a line of parked cars, a lane for bikes, and at least two lanes for autos. Pros and cons: Everybody gets their lane, but that has required widening some of Beijing’s roads to at least seven lanes, and very often twice that, producing not so much roads as “exalting deserts of tarmac,” as a visiting urban planner once put it. Along the way, the buildings on either side get leveled (with or without a fight) and neighborhoods are altered. None of this is the fault of the bike lanes — the roads are being widened, without question, for cars — but none of the options are without tradeoffs.”

“Before cyclists start boarding flights for Beijing like the fellow travellers of yore, know that bicycle production has been falling since 1995 here, and the lanes have been gobbled up by cars ever since. The country has been rapidly losing its attachment to the human-powered two-wheeler that it first glimpsed in the late nineteenth century and regarded as a “foreign horse” or a “little mule that you drive by the ears.” One of the replacements, I’m pleased to say, is the electric bike, which I’ve been driving by the ears for eighteen months and counting. Not surprisingly, I’m an ardent fan of the bike lanes and would seriously rethink my own e-bike evangelism if they disappeared. For a comparison of the situation on both sides of the Pacific, I turned to Ed Wong of the Times. He pedals all over this town, and did so as well in New York a decade ago, before bike lanes had taken off.

On riding a bicycle in Beijing compared to New York City, Edward Wong of the New York Times wrote: “It was always a joy biking through the city, definitely preferable to taking the subway, but it’s no exaggeration to say that I had a close call on virtually all my rides. By comparison, biking in Beijing has been a breath of fresh air (or as fresh as air can be here.) The bike lanes give me a sense of security that was always absent from my experience in New York. As for the argument that bike lanes lead to automobile congestion, that seems absurd from a Beijinger’s point of view. Some studies show that Beijing is now the most congested city in the world. There are many reasons for this, but I have yet to hear any transportation expert cite the bike lanes as a factor.”

“No question that as Beijing has built more roads, drivers have expanded to fill them. But I fear that all of this braying has obscured John’s point that it is not the presence of the lanes he resents, but the manner in which they are being foisted upon him. As he argues, “it should be put to a vote rather than being enacted via bureaucratic diktat.” Bureaucratic diktats are something else that we in Beijing know well. It’s fashionable these days to admire Beijing’s ability to marshal public resources to do things efficiently, whether it’s installing wind turbines on the hillsides or embarking on another eight (yes, eight) new subway lines this year. But the part worth envying is the ambition of a city to envision bold changes and investments — not the ostensible efficiency of a system that deprives people of the right to participate in those choice. As we see everyday here, knocking down houses without adequate due process, in order to modernize the city, might make those neighborhoods more hospitable, but it also has a toxic effect on the political health of the city. Good ideas are good enough to put to a vote.”

According to CBS News: Beijing looked to New York City for tips on adding bicycle lanes. Special lanes are already being built in China's capital to improve safety. [Source: cbsnews.com, March 15, 2016]

Insane Cycling in Guangzhou

On bike riding in Guangzhou, William Foreman of Associated Press wrote: “Cyclists feel themselves being pushed aside. A bike lane near my home is marked with a thick white line, a sign and a bike symbol painted on the pavement. But the line has been chopped up for parking spaces. It’s now a bike lane only when motorists aren’t using it. Anyway, lanes may as well not exist — drivers seem to think their cars are protected by a force field. And it’s not just drivers who are a menace, but pedestrians and even other cyclists. I recently slammed into a migrant worker who blindly pedaled into an intersection. Neither of us was seriously injured, but I badly bruised my hip and wrist as I hit the road and bounced for a few feet. [Source: William Foreman, Associated Press, November 1, 2009]

“While leisure bikes are catching on among Chinese yuppies and college students, few take to the busy streets. Those who do wear helmets, as do I, but we’re a tiny subculture. The commuting laborers don’t wear helmets. Many of the people behind the wheels of the shiny new cars just got their licenses, and their driving sometimes reminds me of my own in high school. Some drivers are courteous to cyclists, perhaps remembering that they were among them not long ago. But others, especially the nouveaux riches in their Audis and BMWs, show an obvious contempt. They cut off cyclists and deny them the right of way. A honk is usually not a warning to be alert, but a “get out of my way” threat.”

“I encountered an extreme example during a training ride with a friend. It was 6:30 a.m. and we were hammering down an empty three-lane thoroughfare at 40 kph when a black Volkswagen Passat behind us opened up with its horn. As it raced beside us we exchanged obscenities until the driver — a beefy man in the kind of crew cut that’s popular with police, military and the mob — swerved in front and nearly knocked us down. Few people seem annoyed by Guangzhou’s cacophony of car horns. Sometimes drivers seem to be beeping just as a way of saying hello to the weird spandex-clad foreigner.”

“Once, while I was barreling through a tunnel, a cement truck rumbled up on my back wheel and the driver started honking. The sound echoing off the tunnel’s walls was deafening. Then I saw the driver and another guy in the cab laughing and yelling “Jia you!” It means “Add fuel!” — a Chinese sports cheer. Being tailgated is especially unnerving because roads are so poor. If your skinny racing tires hit a brick or pothole, you can quickly find yourself under a car.”

“Construction frenzy keeps the roads under a constant cover of dirt, gravel and debris. Water trucks cruise the streets before rush hour each morning, spraying water to control the dust. But they have no sweeping mechanism, so they leave a slippery layer of gritty mud that clogs expensive bike parts and can bring a cyclist down. Each new pothole must be marked on the cyclist’s mental map. Recently after a hard rain, I thought I was speeding through a harmless puddle but it was a hole. It cracked my custom-made bike frame and broke the wheel.”

Speed bumps are another hazard. The Chinese authorities love them. Their purpose seems designed not to slow speeders but to punish them. Rarely are they signposted, and they are usually unpainted and hard to see. Near my home, officials have opted for the cheap option — a thick pipe across the road, anchored by roughly cut spikes of rebar that can slice open a bike tire.Perhaps the most hazardous obstacles are created by the midnight mystery dumpers. Their trucks bring construction waste — cement chunks, broken bricks, scraps of dry wall, splintered plywood — to unlit stretches of road and dump the loads where they can easily bring down any unwary biker.

Bike Sharing in China

Jessica Meyers wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “They’re suddenly outside public toilets, tucked in side alleys, on bridges, near underpasses. The neon colored two-wheelers sit untethered — a reminder of the days when bicycles owned China’s streets, before their rusted remains become stand-in cones for drivers trying to keep a parking space. These bikes are an attempt by two Chinese startups to fuel a cycling renaissance, one fit for a younger generation with Silicon Valley sensibilities. Mobike and Ofo Bicycle allow riders to unlock bicycles with a smartphone and drop them at their destination. While bike-sharing options exist around the world, few have made riding one this simple. [Source: Jessica Meyers, Los Angeles Times, December 13, 2016]

“The rival companies, in just months, have turned Beijing streets into a blur of orange and yellow. They upend the copycat label bestowed on the country’s products and reveal how China, stunted by information barriers and bureaucracy, is also becoming one of the world’s most creative labs for innovation. “We were looking at how cities have become filled with more traffic jams and pollution, and wondered what could we do and what should we do,” said Mobike co-founder Hu Weiwei. Chinese officials are embracing companies like these as they try to revive a slowing economy by promoting innovation.

Josh Horwitz wrote in Quartz: Venture capital firms have poured hundreds of millions of dollars into rival companies, all competing to become China’s “Uber for bikes.” Their premise is simple: Pedestrians looking for a lift can open their smartphones, unlock a bike parked nearby, hop on for a ride, and pay a fee once they arrive at their destination. It’s difficult to overstate how popular these services have become. On almost every street corner in China’s major cities, bikes of different shapes, sizes, and colors are lined up next to one another. [Source:Josh Horwitz, Quartz, February 28, 2017]

“Most bike-sharing schemes, like those in New York or Taipei, require bikes to be parked into designated docks when not in use. There’s often no way to know where these locations are, so riders have to plan out their routes in advance. Or there might be a clunky app, perhaps from the same government agency that funded the program. China’s bike-sharing startups, on the other hand, allow their vehicles to be placed anywhere in the city. Best-in-class engineers have developed GPS-based apps that allow people to find nearby bikes, and charge based on how much time riders spend on them.

“Bullish venture capitalists funded rapid expansion, ensuring companies have plenty of cash to buy bikes and put them on the streets. Prices are dirt-cheap. After paying a small deposit through WeChat or Alipay, two Chinese online payment services, 30 minutes on a bike will cost between 0.5 and 1 yuan ($0.07 and $0.14), depending on the brand.

“As a result, many Chinese have taken up bike-sharing as a replacement for the subway, or even walking. Judy Zhao, a 25-year-old marketing executive, tells Quartz that she takes the bus every day to work, but as soon as she gets off at 5:30pm, she hops on a Mobike to cycle back home. “It’s about 20 minutes to ride [from my office to home], so I only need to pay 0.5 yuan (about $0.07),” she tells Quartz. “It’s cheaper than public transportation.” “It’s cheaper than public transportation.”

Bike-Sharing Companies in China

Numerous companies offer bike-sharing services but two startups lead the pack in terms of venture capital funding: Mobike and Ofo. Mobike is short for mobile bike. Ofo is so-called because the letters look like a bicycle. Mobike had operations in around 100 Chinese cities in 2017. In eight months in 2016 and 2017 it raised over $900 million, including a $600 million financing round led by Tencent Holdings Ltd. The company has also expanded to Singapore, and launched a pilot service for 1,000 bikes in the UK, starting in the cities of Manchester and Salford. [Source: Cate Cadell, Reuters, Jun 15, 2017]

Mobike had 100 million users and supported roughly 25 million rides a day in 2017. Launched in April 2016, it has increasingly integrated features from Tencent's ecosystem, including a tie-up with Wechat, China's most popular social messaging and payments platform with over 900 million users. The firm's app lets users scan QR codes on Mobike-branded bicycles, allowing them to unlock, use and pay for rentals on-demand. Mobike's top competitor, ofo, raised $450 million in May 2017 from a range of investors including Chinese ride-sharing service Didi Chuxing.

Josh Horwitz wrote in Quartz: Mobike, which was founded in late 2015 by a former Uber China employee, first grew popular in Shanghai and is was in 23 cities across China in early 2017. Investors have funded it at lightning speed: It secured two venture capital rounds this year alone that jointly totaled about $300 million. Its backers include Singapore sovereign wealth fund Temasek, along with Foxconn, the manufacturing giant best known for making the iPhone. Chief rival Ofo was founded in late 2014. It grew popular on college campuses in Beijing before raising $130 million last October from nine investors including Xiaomi and Didi Chuxing, the ride-hailing giant that acquired Uber’s China division. On March 1, it announced it closed an additional round totalling $450 million. [Source: Josh Horwitz, Quartz,February 28, 2017]

“Inspired by Ofo and Mobike’s swift uptake in early 2016, rival companies followed suit and a mini-bubble surfaced. About 30 bike-sharing companies (link in Chinese) exist in China right now, with many founded in 2016. Five of those companies went on to raise double-digit funding by year’s end, according to Chinese tech database IT Juzi. Mobike spokesman Xue Huang says that several factors have helped make China ripe for a bike-sharing boom. For one thing, most of the world’s bikes are made in China, which means they can go directly from the factory warehouse to the streets. Roads in China’s major cities tend to be flat and wide, and populations are dense. Most important, unlike in other parts of the world, riding bikes around in China never really went out of fashion. Until only recently, it was the predominant mode of urban transportation.

Bike Sharing in Beijing

As of 2016, Beijing had installed nearly 1,900 racks filled with rental bicycles. They're free for the first hour, and less than $2 for a day. According to CBS News: Beijing was inspired by the success of bike-sharing programs in Paris and Amsterdam. [Source: cbsnews.com, March 15, 2016]

The Yomiuri Shimbun reported, “bicycles with vivid orange and yellow frames have been easy to spot in large cities like Beijing due to a rise in bicycle-sharing schemes. Fees differ among the various bicycle-sharing companies, as well as the colors of the bicycles, but the main structure of their systems is the same. Users first have to download an app on their smartphone to register their IDs, and then pay a deposit using an electronic service. After that, they will be able to look for a bicycle using the designated smartphone app, which displays the location of bicycles via a Global Positioning System device attached to each one. Next, they can unlock an available bicycle by scanning an attached QR code with their smartphone. When they lock the bicycle at the destination, a fee of 0.5-1 yuan (about 8 yen-16 yen) per 30 minutes is paid automatically via an e-payment. [Source: Igarashi, Aya, Yomiuri Shimbun, April, 2017]

Mobike pioneered the service. A dozen or so firms have joined the market since, and the number of bicycles available in 30 or more cities across the nation topped 1 million. Some even estimate the figure will reach 20 million within the year. Bicycle sharing has entirely changed the monotonous scenery of the city. Fashionably attired young people on brightly colored bicycles briskly cycle alongside cars. The number of illegal bike taxis is decreasing, and some car lanes are being partitioned as cycle-only lanes. Moreover, citizens' awareness is also changing to the realization no one can escape from traffic and air pollution no matter how much money you have or how luxurious your car is.

Problems for Bike-Sharing Companies in China

Widespread customer negligence and razor-thin margins could make it hard for bike-sharing businesses to stay afloat in China. Josh Horwitz wrote in Quartz: The very factors that make China’s bike-share services so convenient—low prices and ease-of-use, namely—are the same factors that could spell their death. “What they’ve got is a very interesting technology, but a basic business model that makes no sense,” says Paul Gillis, who teaches accounting at Peking University in Beijing. [Source: Josh Horwitz, Quartz,February 28, 2017]

“While Mobike, Ofo, and their many rivals are easy to use, they’re equally easy to abuse. The companies basically rest on the “honor system,” and consumer negligence poses a serious threat to their long-term viability. The “park anywhere” policy is a blessing and a curse. On the one hand it increases the likelihood that bikes will be found in one’s immediate vicinity. But it also allows riders to park their bikes in remote locations with no nearby foot-traffic. As a result, bikes parked along freeways are now a common sight in China. Bikes parked along freeways are now a common sight.

“Property managers, meanwhile have started to complain about bikes taking up space besides private buildings, or blocking pedestrians on the sidewalk. News reports of bike-share vehicles piling up in dumpsters, ditches, rivers, and even trees (link in Chinese) make regular appearances on Chinese social media. To manage this problem, Mobike and other companies rely on volunteer users to spot and report discarded bikes. But they have also hired in-house teams specifically for rounding up these dispersed bikes, and taking them to high-traffic hubs or repair centers. That costs money. Uber and Didi don’t have to deal with this problem, since those companies generally don’t own the cars connected to their apps.

Then there’s the problem of theft and vandalism. Mobike vehicles lock and unlock when a rider scans the QR code attached to a bike. But many people—perhaps employees at competing companies—will deface these QR codes, rendering the bikes unusable. The QR code that use to unlock the bikes are scratched sometimes. Ofo bikesunlock when a user scans the bike plate, receives a four-digit password via smartphone, and then inputs the code into an old-fashioned mechanical lock. But these mechanical locks have permanent passwords. Users can simply memorize the password of a particular bike, unlock the mechanical lock, and re-secure it using their own personal lock. This lets users effectively steal the bike after first use, and ride it without being bound to the app’s timer. Recently, two nurses in Beijing spent five days in jail after they were caught using this trick on Ofo’s bikes—though most such riders probably go about unnoticed.

“All of these factors merely compound the stress placed on an already shaky business model. Mobike and its rivals won’t reveal how much their bikes cost to produce, but an old estimate (which Mobike says has since decreased) places the cost of a standard Mobike at 3,000 yuan (about $437). Professor Gillis says that fares alone will hardly recoup these costs in a timely manner—let alone cover labor and R&D expenses. “They rent for one yuan every half hour, and they expect that they might be rented four times a day for a half hour, which amounts to four yuan per day,” he tells Quartz. “If you take four yuan per day and you take that into the 3,000 yuan, you’ve got a long time before you’ve recovered the cost of a bike.”

Bicycle Production in China

Each year China produces 17½ million bicycles, three times as many bicycles as it nearest rivals, Japan and the U.S. If these bicycles were lined up together they would stretch three quarter of the way around the world. In the Mao and Deng eras China produced even more. At its peak, the Shanghai Forever Bicycle Company alone produced 33.5 million bicycle every year, and one out of every four Chinese rode a bicycle made at this factory. Most of the bikes made there were black one-gear models made from water pipe known as Flying Pigeons. Models exported to the U.S. were called Wind Catchers. Many of the sophisticated road bikes and mountain bikes sold around the world today are made in China or Taiwan.

The European Union (E.U.) and China have clashed over the import of bicycles to Europe. At one point in 2016 a dispute over 25 million euros and about half a million cheap bicycles imported from China into the E.U. caused the collapse of trade talks involving more than one trillion US dollar. [Source: Bike-ey.com. December, 2016]

Bob Megvicius, a director of the Bicycle Product Suppliers Association and vice-president of Specialized, told The Guardian: Chinese companies have done an excellent job in making capital investments in automation and new technologies and in finding ways to improve the efficiency and the productivity of the products that they're producing. It's very hard for us to look at other places and replicating it." He said that 90 per cent of the bicycles imported to the US each year originate from China for a total of 14-15 million each year, but tariffs in 2019 led to a fall of 450,000 bicycles imported in the first quarter of 2019 alone. [Source: Simon MacMichael, The Guardian, June 19, 2019]

The coronavirus pandemic increased demand for bikes. Bicycle manufacturing skyrocketed in China and Taiwan, fueled by global demand sparked by fear of contracting the coronavirus on crowded buses and trains in Europe or America, or by the need for outdoor activities after weeks of confinement.

Bicycle Industry in China

According to Ibis World: Revenue in the bicycle manufacturing industry in China fluctuated from 2017 to 2021 and grew at an annualized 1.7 percent to total $13.8 billion. This growth includes a 4.8 percent increase in 2021. Developments in the industry were mainly driven by steady domestic demand growth stemming from rising household income, the bicycle sharing sector, product innovation, increased environmental consciousness, and growing traffic congestion due to China's rapid urbanization process. [Source: Ibis World, November 30, 2021]

Profit margins for standard bicycles are projected to remain low due to intense price competition and increasing production costs. However, the industry's overall profit margin is anticipated to slightly increase through the development of high-end markets. As general bicycle prices are anticipated to remain low in the domestic market, consumers will not be highly sensitive to price changes. Therefore, manufacturers must design new bicycles to attract potential buyers. As the industry has entered its mature stage, more mergers and acquisitions will likely occur in the future

There are 1,730 bicycle-related businesses in China and the industry employs 147,071 people. The biggest companies include 1) Giant (China) Co., Ltd., 2) Tianjin FUJITA Group Co., Ltd., 3) Shimano Group, 4) Ming Cycle Industrial Co. Ltd. and 5) Guangdong Tandem Industries Co., Ltd. New Jersey-based Kent International was the second largest bike manufacturer in 2019 after Giant. Merida is another Taiwan-based company that manufactures a lot of bikes in China and is one of the world’s biggest bike companies.

From 2012 and 2017 annual revenue was $12.2 billion and annual growth was 4.7 percent. A total of 689 businesses employed 150,216 people. The main drivers of industry growth during this period were increasing domestic demand, particularly in China's rural regions, and export growth. In 2017, exports accounted for 41.5 percent of total revenue. Intense competition in this mature industry and the rising price of inputs have led to falling profitability over the past few years. In 2017, average industry profit is estimated at 5 percent of revenue.

Giant

Giant Manufacturing Co. Ltd. (commonly known as Giant) is the world’s biggest bike manufacturer. The Taiwan-based company sells more than 6 million bicycles annually. Giant has manufacturing facilities in Taiwan and China. In the past two decades many of its frames, bike parts and bokes have been made in China. As part of its effort to "move production close to your market," Giant has built factories in the Netherlands and in Gyongyos, Hungary for the European market as well as seeking a partner in Southeast Asia where Vietnam is a major bicycle exporter. [Source: Simon MacMichael, The Guardian, June 19, 2019]

Giant was established in 1972 in Dajia, Taichung County in Taiwan (now part of Taichung City), by King Liu and several friends. A major breakthrough came in 1977 when Giant's chief executive, Tony Lo, negotiated a deal with Schwinn to begin manufacturing bikes as an OEM, manufacturing bicycles to be sold exclusively under other brand names as a private label. As bike sales increased in the U.S., and after workers at the Schwinn plant in Chicago went on strike in 1980, Giant became a key supplier, making more than two-thirds of Schwinn bikes by the mid-1980s, representing 75 percent of Giant's sales. When Schwinn decided to find a new source and in 1987 signed a contract with the China Bicycle Company to produce bikes in Shenzhen, Giant established its own brand of bicycles to compete in the rapidly expanding $200-and-above price range. [Source: Wikipedia]

Giant not only produces bikes old under its name it assembles bikes and makes bike frames for a client list that has included major brands such as Specialized, Trek, Scott and Colnago. In 2018, Giant had sales in over 50 countries, in more than 12,000 retail stores. Its total annual sales in 2017 reached 6.6 million bicycles with revenue of US$1.9 billion. Most of its bikes are sold in the European Union, the United States, Japan and Taiwan.

Giant is the world’s biggest bike exporter, accounting for as much as 10 percent of the market, according to JPMorgan. It shipped 6.6 million units in 2014, with global sales of $1.6 billion, up 10.4 percent from 2013, with 5.1 percent growth expected in 2015. Growth has been impressive in the US and Europe – despite a 14 percent EU tariff introduced for finished bicycle imports – although it has been hindered by the slowing Chinese economy. [Source: Alison Ratcliffe, Supply Chain, January 26, 2016]

Giant suffered after U.S. President Donald Trump raised tariffs on Chinese-made bicycle sold in the U.S. to 25 percent in 2019. The tariffs imposed by the US have added an average of $100 to Giant bikes sold there that have been made in China. The company closed one factory in China and moved production of bikes destined for the US market out of the country. Giant Chairwoman Bonnie Tu told Bloomberg that the company’s factory in Taiwan is now operating double shifts to satisfy demand and said that "the era of Made In China and supplying globally is over." She said that differing tariffs between countries mean that "the world as a level playing field in terms of commerce" no longer holds true. [Source: Simon MacMichael, The Guardian, June 19, 2019]

The coronavirus pandemic increased demand for Giant's bikes. Giant planned to build a new large plant in the European Union. In addition, the company moved factories from China to Taiwan. Giant’s revenues increase 55 percent in the first quarter of 2021. E-bikes accounted for 30 percent of sales.

E-Bikes in China

Electric bikes known s as e-bikes have become very popular in recent years. Costing $200 to $300, they can reach a top speed of 30kph and go 50 kilometers (more with pedaling) on a single charge of electricity that costs 16 cents. The lead-based batteries can be charged overnight. They last for about a year before needing to be replaced and can be recycled. In some cities they account for 50 percent of all bicycles used.

About 20 million e-bicycles were sold each year in 2007 and 2008. Some buyers are former car owners. One 45-year-old saleswoman told the Washington Post, “My family bought our first car in the 1990s but we sold our car last year. Having a car is not that convenient, compared with an e-bike.” Alexander Wang of the National Resources Defense Council told the Washington Post, “The real sweet spot will be if China’s e-bike explosion leads to the development of electric cars and the infrastructure for charging these e-vehicles. China is probably better positioned to make this leap than any other country in the world.”

Evan Osnos wrote in The New Yorker, “Traffic alone made it hard to get around... In desperation, I decided to buy an electric bicycle. China has put a hundred million of them on the road in barely ten years, an unplanned phenomenon that, energy experts point out, happens to be a milestone: the world’s first electric vehicle to go mass market. Hunting for an e-bike, I ended up at a string of shops near the Tsinghua campus, where each storefront offered a competing range of prices and styles to a clientele dominated by students and young families. I settled on a model called the Turtle King — a simple contraption, black and styled like a Vespa, with a five-hundred-watt brushless motor and disk brakes. Built of plastic to save weight, it was more akin to a scooter than to a bicycle, and it ran on a pair of lead-acid batteries, similar to those under the hood of a car. The salesman said that the bike would run for twenty to thirty miles, depending on how fast I went, before I would need to plug its cord into the wall for eight hours or lug the batteries inside to charge. With a top speed of around twenty-five miles per hour, it would do little for the ego, but, at just over five hundred dollars, it was worth a try. [Source: Evan Osnos, The New Yorker, December 21, 2009]

“The manager rang up the sale, and I chatted with two buyers who were students at the Beijing University of Aeronautics and Astronautics. “You must have tons of these in the U.S., because you’ re always talking about environmental consciousness,” one of them, an industrial-design major wearing a Che Guevara T-shirt, said. Not really, I told him; American drivers generally use bikes for exercise, not transportation. He looked baffled. Around his campus and others in Beijing, electric bikes are as routine as motorcycles are in the hill towns of Italy.”

“I eased the Turtle King down over the curb and accelerated to full speed, such as it was. I threaded through an intersection clotted with honking traffic, and the feeling, I discovered, was sublime. The Turtle King was addictive. I began riding it everywhere, showing up early for appointments, flush with efficiency and a soupçon of moral superiority. For years, people had abandoned Beijing’s bicycle lanes in favor of cars, but now the bike lanes were alive again, in an unruly showcase of innovation. Young riders souped up their bikes into status symbols, pulsing with flashing lights and subwoofers; construction workers drove them like mules, laden down to the axles with sledgehammers and drills and propane tanks; parents with kids’ seats on the back drifted through rush-hour traffic and reached school on time. Before long, I was coveting an upgrade to a lithium-ion battery, which is lighter and runs longer. (Lithium-ion batteries have sparked interest in electric bikes in the West. They are a high-minded new accessory in Paris, and more than a few have even turned up in America.)”

“As a machine, the Turtle King was in desperate need of improvement. The chintzy horn broke the first day. The battery never went as far as advertised, and it was so heavy that I narrowly missed breaking some toes as it crashed to the ground on the way into the living room. Soon, the sharp winter wind in Beijing was testing my commitment to transportation al fresco. And yet, for all its imperfections, the Turtle King was so much more practical than sitting in a stopped taxi or crowding onto a Beijing bus that it had become what all new-energy technology is somehow supposed to be: cheap, simple, and unobtrusive enough so that using it is no longer a matter of sacrifice but one of self-interest.”

China’s alternative 863 energy Program has added a program to build a micro-electric car, inspired by bicycle components, for commuters. “Researchers at Tsinghua did just that, by attaching four electric-bike motors to a chassis. “We call it the Hali,” Ouyang Minggao, the Tsinghua professor in charge of it, told me. They took the name from the Chinese translation of “Harry Potter.” The car is tiny and bulbous, and is being road-tested near Shanghai.

Image Sources: 1) Columbia University; 2) BBC, Environmental News; 3, 7) University of Washington; 4, 5, 6) Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html ; Julie Chao, Wiki Commons ; YouTube

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2022