CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM

Civil service exam hall

China the world's largest educational system in terms of numbers of students. Although the quality of schools varies widely in China, there are standard textbooks and curricula for all subjects at all levels. The textbooks convey a strong nationalist message in content. Teaching style emphasizes the authority of the teacher and demands great amounts of memorization and recitation. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

China has a vast and varied school system. There are preschools, kindergartens, schools for the deaf and blind, key schools (similar to college preparatory schools), primary schools, secondary schools (comprising junior and senior middle schools, secondary agricultural and vocational schools, regular secondary schools, secondary teachers' schools, secondary technical schools, and secondary professional schools), and various institutions of higher learning (consisting of regular colleges and universities, professional colleges, and short-term vocational universities). [Source: Library of Congress]

China has a top-down education system. Education in China is the responsibility of the Ministry of Education. Local school systems are expected to follow orders from the Education Ministry. School administrators are expected to follow orders from the local education bureaucrats. Teachers are expected to follow orders of school administrators. Students are expected to follow orders of teachers. Although the government has authority over the education system, the Chinese Communist Party has played a role in managing education since 1949. The party established broad education policies and under Deng Xiaoping, tied improvements in the quality of education to its modernization plan. The party also monitored the government's implementation of its policies at the local level and within educational institutions through its party committees. Party members within educational institutions, who often have a leading management role, are responsible for steering their schools in the direction mandated by party policy.

The Chinese education system favors those in the cities. In rural areas schooling often is unavailable or prohibitively expensive. One study found that rural children have only a third of chance of getting into university as urban children. Hu Xingdu, a sociologist at the Beijing Institute of Technology told the Washington Post, “Farmers don’t see a bright future from receiving more education. Many believe it won’t help them much in making money. They also can’t afford to send their children to university and a university degree no longer guarantees a job after gradation.”

See Separate Articles: EDUCATION IN CHINA: STATISTICS, LITERACY, WOMEN AND TEST SCORE SUCCESSES Factsanddetails.com/China ; TRADITIONAL VIEWS ON EDUCATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HISTORY OF EDUCATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; VILLAGE EDUCATION AND SCHOLARS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; SCHOOL CURRICULUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PROBLEMS WITH THE CHINESE EDUCATION SYSTEM factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: Education System: “Who's Afraid of the Big Bad Dragon?: Why China Has the Best (and Worst) Education System in the World” by Yong Zhao, Emily Zeller, et al. Amazon.com; “Educational System in China” by Ming Yang (2009) Amazon.com; : Education: “The Learning Gap: Why Our Schools Are Failing and What We Can Learn from Japanese and Chinese Education” by Harold W. Stevenson and James W. Stigle Amazon.com; “Education for Life” (China Academic Library) by Xingzhi Tao Amazon.com; “Education in China: Philosophy, Politics and Culture” by Janette Ryan Amazon.com; In the Past: “Confucian Philosophy for Contemporary Education” (Routledge International Studies in the Philosophy of Education) by Charlene Tan Amazon.com; “Neo-Confucian Education: The Formative Stage” by Wm. Theodore de Bary and John W. Chaffee Amazon.com; “Education and Society in Late Imperial China, 1600-1900" by Benjamin A. Elman and Alexander Woodside Amazon.com; “The Education of Girls in China” by Lewis Ida Belle (1887- 1969) Amazon.com; “The Chinese System of Public Education” by Ping Wen Kuo (1915) Amazon.com; Mao Era: “Radicalism and Education Reform in 20th-Century China: The Search for an Ideal Development Model” by Suzanne Pepper Amazon.com; “The Chinese System of Public Education (Columbia Univ Teachers College) by Ping-Wen Kuo (1972) Amazon.com;“My Family: a Normal Intellectual Family Suffered under the Rule of the Communist Party of China” by Luowen Yu Amazon.com; After Mao Era: “Social Changes and Yuwen Education in Post-Mao China by Min Tao Amazon.com; “In Search of Red Buddha: Higher Education in China After Mao Zedong, 1985-1990" by Nancy Lynch Street Amazon.com

Chinese Education Under the Communists

Red Guards burn books

The goal of the early Communist education policy was to teach the masses how or read and write, and channel talented young people into science and technology. It was oriented more towards meeting the needs of society and the state rather than fostering individual development. Schools were free, compulsory, universal and classless and were used disseminate Communist doctrine as well as educate children. Every school has a Communist Party secretary who outranks the principal, ensuring control over education. The Chinese education system has been touted as providing a “a fair pathway to advancement” but is often criticized for not providing enough money for primary and secondary education and for not doing more to improve the poor-quality of Chinese universities.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “The Chinese have always regarded education as a tool for strengthening the country instead of cultivating individuals, which dictates that learning for the sake of knowledge is not enough. Students are expected to develop, first, as patriotic Chinese with strong morals, then as individuals with the necessary skills to serve the country and people. Throughout the educational system, the ideal of a well-rounded, cultured person with a strong socialist consciousness is deeply embedded. Article 46 of the Constitution, adopted on December 4, 1982, stipulates that "citizens of the People's Republic of China have the duty as well as the right to receive education." It also states that minorities "have the freedom to use and develop their own spoken and written languages" (Article 4), and the blind, deaf-mute, and other handicapped citizens should receive help from the state to improve their education (Article 45). The most important provision of the 1982 Constitution on education is Article 19. It states that "the state develops socialist educational undertakings and works to raise the scientific and cultural level of the whole nation." It sets the nation's educational goal as "to wipe out illiteracy and provide political, cultural, scientific, technical, and professional education" for China's citizens, and "encourages people to become educated through self-study." These principles set the keynote for subsequent legislation in the 1980s and 1990s. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“The document that led to the rehabilitation and expansion of education in post-Mao China was the 1985 Decision on the Reform of China's Educational Structure. It stated that the major goal of the reform was to develop education as a significant tool of socialist construction, economic expansion, and modernization. To this end, the reform document specifically called for a commitment to a compulsory nine-year cycle of primary and middle school education, diversifying high school education, expanding vocational education, improving teaching quality, granting more autonomy to higher educational institutions, reforming the job assignment system, and allocating more responsibility to education professionals over party officials.

“In February 1993 the Central Committee of the Communist Party, together with the State Council, officially distributed the Outline for Reform and Development of Education in China. This document details strategic tasks to guide education reform in the 1990s and into the next century. The Outline calls the nation to make education a strategic priority because of its fundamental importance to China's modernization drive to raise the ideological and ethical standards of the entire population, as well as to raise its scientific and educational levels. The main tasks include gearing education to the needs of the future modernization efforts, improving the quality of the workforce, and establishing an educational system suited to a socialist market economy (Ashmore & Cao 1997).

Constitutional Right to an Education

Constitutional Provision on the Right to Education The 1982 Constitution of the People’s Republic of China (PRC or China) declares that a citizen has not only the right, but also the obligation to receive an education. Specifically, article 46 of the Chinese Constitution states as follows: [c]itizens of the People’s Republic of China have the duty as well as the right to receive education. The State promotes the all-round development of children and young people, morally, intellectually, and physically. Article 46, however, does not explicitly provide for a fair and equal right to education. Equality is provided by paragraph 2 of article 33 of the Chinese Constitution, which states that “[a]ll citizens are equal before the law.” [Source: Laney Zhang, Foreign Law Specialist, Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2016 |*|]

Impact on Legislation: The PRC Law on Education (Education Law) was promulgated in accordance with the Constitution. In addition to repeating the constitutional declaration of the right to education, article 9 of the Education Law explicitly provides for the equal right to education: Citizens of the People’s Republic of China shall have the right and obligation to receive education. All citizens, regardless of ethnic group, race, sex, occupation, property status, or religious belief, shall enjoy equal opportunities for education according to law. |*|

Court Decision: Although in practice the implementation of the equal right to education as provided by the Constitution and the Education Law may still be problematic, a historic court ruling issued in 2001 specifically affirmed the constitutional right to education. |In 1990, the plaintiff, Qi Yuling, passed the entrance examination and was admitted by a specialized secondary professions school in Shandong Province. The defendant, a classmate of Qi who failed the examination, stole Qi’s admission letter and, with the help of other defendants including her father, studied under Qi’s name and went on to take a good job in a bank upon graduation. Qi did not find this out until a decade later, during which time she was not able to find a good job due to her lack of a technical education. The first-trial court ordered emotional damages caused by the infringement of Qi’s right to her name, which is protected by civil law, but declined to provide a remedy for the alleged violation of her right to education protected by article 46 of the Constitution. |*|

On appeal, the Shandong High Court requested a judicial interpretation from the Supreme People’s Court (SPC). The SPC held in a reply issued in 2001 that the plaintiff’s “basic right to education as provided by the Constitution” was violated. The Shandong High Court went on to order higher damages based on the defendants’ infringement of the plaintiff’s constitutional right to education. |*|

The Qi Yuling case is called China’s “first constitutional case” inasmuch as, in recognizing the constitutional right to education, the SPC explicitly cited a constitutional provision as the legal ground for a judicial decision or interpretation for what is believed to be the first time. However, it appears there have not been any subsequent cases decided on constitutional grounds following the Qi Yuling case. In fact, in December 2008, the SPC under a new president issued a document that officially voided the aforementioned judicial interpretation. |*|

Compulsory Education Law

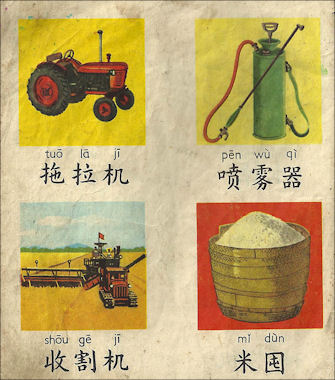

Cultural Revolution textbook

In 1986 the goal of nine years of compulsory education by 2000 was established. The Law on Nine-Year Compulsory Education, which took effect July 1, 1986, established requirements and deadlines for attaining universal education tailored to local conditions and guaranteed school-age children the right to receive education. People's congresses at various local levels were, within certain guidelines and according to local conditions, to decide the steps, methods, and deadlines for implementing nine-year compulsory education in accordance with the guidelines formulated by the central authorities. The program sought to bring rural areas, which had four to six years of compulsory schooling, into line with their urban counterparts. Education departments were exhorted to train millions of skilled workers for all trades and professions and to offer guidelines, curricula, and methods to comply with the reform program and modernization needs. [Source: Library of Congress]

Compulsory education serves two purposes: to prepare students for employment and to enable them to lay a solid foundation for entering schools of higher level. China's Law on Compulsory Education (Compulsory Education Law) codifies school-age children the right to receive nine years of compulsory education (a six-year primary school and a three-year middle school). The law lays down the principle that the state shall establish a funding system to guarantee implementation of compulsory education. Under the Compulsory Education Law, children shall be sent to school at the age of six (or seven in the undeveloped areas) to receive education, and no tuition fees and miscellaneous fees shall be charged during the nine years of compulsory education. In order to promote balanced development of all the schools, the local government educational authorities are prohibited from dividing schools into key schools and ordinary schools, and the schools are prohibited from dividing classes into elite classes and non-elite classes, which were actually the common situation before implementation of the law. The law also bans any entrance examinations for basic education. [Source: Library of Congress Law Library, Legal Legal Reports, 2007 |*|]

The curriculum in all Chinese schools is decided by the governmental educational authority, namely the Ministry of Education. Text books will be reviewed and may be censored by the government and may not be used without pre-approval of the state. The local-level governments implementation of their statutory obligations of compulsory education varies from the economically developed east to the undeveloped west, from urban areas to the rural areas. According to a report by an official news agency in 2006, China “will exempt primary and junior high school students in its rural west from tuition and other education expenses this year, pledging to implement similar policies in other areas starting 2007, ” evidencing that at least in the western rural areas, compulsory education has not been fully established. The government published a national net enrollment statistic ratio to primary schools, which is 99.2 percent in 2005. This number may have excluded the children of the migrant workers in the cities, who are not present at their household registration addresses and therefore hard to be calculated in the statistics. Their education resources are so insufficient that in 2003, the State Council circulated an official notice urging the local-level governments to improve equal education rights of the migrant children, in which it admits that the education of the migrant children has been an increasingly difficult problem of the county. Approximately 9.3 percent of the “migrant children” (those moving with their parents from villages to cities) do not get access to schools in the cities, according to a report of the China Youth Daily, a government related newspaper. |*|

Provincial-level authorities were to develop plans, enact decrees and rules, distribute funds to counties, and administer directly a few key secondary schools. County authorities were to distribute funds to each township government, which were to make up any deficiencies. County authorities were to supervise education and teaching and to manage their own senior middle schools, teachers' schools, teachers' in-service training schools, agricultural vocational schools, and exemplary primary and junior middle schools. The remaining schools were to be managed separately by the county and township authorities.

“The compulsory education law divided China into three categories: 1) cities and economically developed areas in coastal provinces and a small number of developed areas in the hinterland; 2) towns and villages with medium development; and 3) economically backward areas. The third category, economically backward (rural) areas (around 25 percent of China's population) were to popularize basic education without a timetable and at various levels according to local economic development, though the state would "do its best" to support educational development. The state also would assist education in minority nationality areas. In the past, rural areas, which lacked a standardized and universal primary education system, had produced generations of illiterates; only 60 percent of their primary school graduates had met established standards.

Ministry of Education

The Ministry of Education of the People's Republic of China is a cabinet-level department under the State Council responsible for basic education, vocational education, higher education, and other educational affairs across the country and accredits tertiary institutions, curriculum, and school teachers. Headquartered in Xicheng, Beijing, the Ministry of Education was established in 1949 as the Ministry of Education of the Central People's Government, and was renamed the State Education Commission of the People's Republic of China from 1985 to 1998. Its current title was assigned during the restructuring of the State Council in 1998. [Source: Wikipedia]

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: The educational system is almost entirely centralized in China. The first National Ministry of Education (MOE) was founded in 1952 and patterned closely on its Soviet counterpart. It experienced reorganization three times before 1966. When the Cultural Revolution broke out in 1966, the Red Guards, with the support of Mao Zedong, abolished the entire educational administration in China. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

“A single Ministry of Education was re-established in 1975. As the political situation in China became more stable, the MOE was consolidated by the State Council. On June 18, 1985, a major reorganization of central educational administration took place in China. The 11th Plenary of the Standing Committee of the People's Congress in China passed a resolution that called for the abolition of the Ministry of Education and the establishment of the State Education Commission (SEC), a multi-functional executive branch of the State Council.

The Ministry of Education is the supreme administrative authority for the education system in China and is responsible for turning out personnel well-educated and well-trained in various subjects and fields for China. For the first time in China's history, those who have assumed direct command of the country's educational system have high positions in the State Council. The SEC formulates major educational policies, designs overall strategies for promoting education, coordinates educational undertakings supervised by various ministries, and directs education reform.

In November 2009, amidst rising criticism over the quality of schools and the high number of jobless college graduates, China’s minister of education, Zhou Ji, was dismissed by the Chinese legislature after six years on the job and replaced him with a deputy. His dismissal follows revelation of a corruption scandal involving a university in Wuhan, where Zhou had been mayor and, before that, president of another university. Zhou has not been publicly linked to the corruption charges, but many suspect he may have been involved somehow. Zhou became education minister in 2003, but he was widely criticized for moving too slowly on problems such as the underfunding of primary and secondary schools and poor standards in higher education to correct them. [Source: Michael Wines, New York Times, November 3, 2009]

Education Reforms in the 1990s and 2000s

China’s education system is plagued with problems, such as underfunding of primary and secondary schools and poor standards in higher education. In the 1990s a move was made to reduce the emphasis on entrance exams, encourage “social forces” and make it easier to establish private schools. During this time parents who were denied an education by the Cultural Revolution pushed their “Little Emperors” to study and work hard in school. The privatization of schooling and the increase in the number of schools occurred swiftly in the 1990s and early 2000s.

There have been a lot of calls for reform of the exam system. Some provinces have introduced their own tests. Fudan University has taken the step of admitting students based on a broad criteria not only the entrance exam. There is still a lot of resistance to changing the exam system in part because of concerns that if the test system were abandoned or down played the admission process would be affected by corruption and cronyism.

Since the late 1990s there has been an emphasis on improving China’s education system by upgrading rural schools and quintupling the size of the university system and bringing more critical thinking and creativity into the classroom. To achieve these goals there has been an effort to introduce better textbooks and train teachers in new teaching methods such as teaching students in groups.

In November 2009, China’s unpopular education minister Zhou Ji was ousted by the Chinese legislature amid a corruption scandal and displeasure with the education system. The corruption scandal centered on bribery at the main university in Wuhan, where Zhou worked in the education system and was mayor.

On reforming the Chinese education system, Jiang Xueqin, deputy principal of the Peking University High School, wrote in The Diplomat: “First, every Chinese can agree that this new education system ought to be a meritocracy and that the most diligent and brightest students ought to reach the top. Second, every Chinese can agree that China has limited education resources for too many people; while it would be nice to educate everyone to the best ability of the state as is the case in Finland and Singapore, China is too poor to do so. Third, China is a guanxi-based society with little respect for institutions, processes, and laws; whatever new system that everyone agrees to must be able to resist the pull and power of the well-connected and wealthy. Fourth, Chinese can agree that education is first and foremost about social mobility (rather than about national economic development), about the opportunity for anyone who is willing to work hard to rise in society.” [Source: Jiang Xueqin The Diplomat. June 3, 2011]

In June 2010, China’s leaders released the National Outline for Medium- and Long-Term Educational Reform and Development. President Hu Jintao stressed that education was the key to social development and promised to improve quality and accessibility in the coming decade. The document, which highlights China's strategic goal for education before 2020, promises to reform the annual gaokao and force high schools, colleges and universities to adopt more flexible enrollment policies. The plan pledges to guarantee equal access to education while improving quality and balancing the development of compulsory education in urban and rural areas. [Source: : Mitch Moxley, Asian Times, July 2010]

In September 2010, Chinese President Hu Jintao, during a visit to the Renmin University of China in Beijing and its affiliated high school, called on teachers to embrace reform and innovation in teaching and enhance teaching standards. At the high school, after observing some art classes, Hu urged school authorities to respect students' individuality, tap their potentials, and help students improve their overall competence. He called on the country's teachers to learn from the model teachers, cultivate noble virtues, improve their professional standards and make greater contributions to the scientific development of the country's educational cause. [Source: China Daily, September 10, 2010]

Much-Lauded Shanghai Education System

In 2009, Shanghai ranked at the top in reading, mathematics and in science out of 65 countries in the OECD academic aptitude tests conducted by Program from International Student Assessment (PISA). Heather Singmaster wrote for the Asia Society: Shanghai, the largest city in China, was the first to achieve one hundred percent primary and junior high school enrollment. It was one of the first to achieve almost universal secondary school attendance. Also notable is that all students in Shanghai who want to attend some type of higher education are able to do so. Universal education involved including children of migrant workers from rural areas of the country – amounting to 21 percent of school children in the city. (With a population of nearly 20 million, that's nearly four million migrant school children.) In other parts of China, these children may be seen as a problem. Shanghai, however, is a city fueled by migrants, and it embraced this population and integrated these children into its classrooms. [Source: Heather Singmaster, Asia Society; based on Chapter 4 of "Shanghai and Hong Kong: Two Distinct Examples of Education Reform in China” in the publication "Strong Performers and Successful Reformers in Education: Lessons from PISA for the United States", OECD (2010)]

China’s education system has struggled to move away from the exam-based system that drives curriculum and results in memorizing facts to pass the test. In 1985, Shanghai began a process of reform and created exams that test the application of real-life skills. Multiple choice questions no longer appear on the city’s exams.

Despite the reforms, exams still exist. An estimated 80 percent of students attend night and weekend “cram schools” to ensure that they pass. This comes in addition to nightly homework and extracurricular activities – making the life of a Chinese student overwhelming. The central Chinese government is aware of this countrywide problem and its new 2020 reform efforts call for a reduction in student workload. Shanghai is additionally working to improve students’ education experience so that they learn to learn and not just learn many facts. An updated curriculum is at the center of this process.

Beginning in 1985, in an attempt to move away from the high-pressure exam system and increase the quality of education, Shanghai began to allow students to take elective courses, which led to new textbooks and materials. Implemented in 2008, a renewed effort to encourage student learning rather than accumulation of knowledge, led to eight curricular “learning domains”: 1) language and literature; 2) mathematics; 3) natural science; 4) social sciences; 5) technology; 6) arts; 7) physical education; and 8) practicum

Schools were then encouraged to create their own curriculum and outside groups such as museums became partners in education. Part of the new curriculum includes an emphasis on inquiry-based education. Students independently explore research topics of interest to themselves in order to promote social wellbeing, creative and critical thinking, and again, learning to learn.

To support the new education changes, certification processes for teachers were implemented. Teacher professional development requirements also increased – teachers in Shanghai must now complete 240 hours of professional development in five years. An online database provides help with design and implementation of curriculum, research papers, and best practice examples. Teachers are now encouraged to allow time for student activities in classrooms rather relying solely on presentations.

One interesting strategy employed by Shanghai to improve weak schools is the commissioned education program. Under this scheme, top performing schools are assigned a weak school to administer. The “good” school will send a team of teachers and a principal to lead the school and improve it. This has been happening within the city but also as a type of exchange program with poor rural schools. Such a system assists the poor schools and benefits Shanghai schools by allowing them to promote teachers and administrators.

Comparing the Chinese and U.S. Education Systems

Some say the U.S. is behind China in education , according to some measures. Jia Lynn Yang wrote in Washington Post: Most famously, on a test given to 15-year-olds around the world by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development, Chinese students in Shanghai came in No. 1in all three categories: reading, science and math. The United States ranked 14th, 17th and 25th, respectively. But Yong Zhao, an expert on China’s education system, said the PISA test, as it’s known, is a misleading measurement of the quality of a country’s schools. He said China’s schools don’t do well at teaching creative thinking and encouraging students who might one day found companies. [Source: Jia Lynn Yang, Washington Post, November 16, 2012]

“In the United States, “the glorification of China is rampant,” said Zhao, associate dean for global education at the University of Oregon’s College of Education. Zhao grew up in the Chinese education system and immigrated to the United States after college. But in China, he said, officials worry about whether the schools can cultivate “the next Steve Jobs,” something that Zhao says is difficult because the curriculum is so test-based.

“He said China is in the middle of reforming its education system to look more like — surprise! — the one in the United States. Meanwhile, the United States is increasing standardized testing, a shift that in a way moves this country’s approach closer to China’s. As China becomes wealthier, more families can afford to send their children to college. People with some college education make up about 9 percent of China’s population, up from 3.6 percent in 2000. By comparison, more than one-third of Americans have some college education.

“But in China, in another parallel with the United States, a college degree is no guarantee of success. For the past few years, there has been a chronic unemployment problem among Chinese college graduates, who often live with their parents to save on housing costs — much like their American counterparts. While China has plenty of low-paying jobs in factories, there isn’t much high-skilled office work.

Image Sources: Landsberger Posters ; Columbia University University of Washington; Ohio State University, Wiki Commons, Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022