SCHOOL LIFE IN CHINA

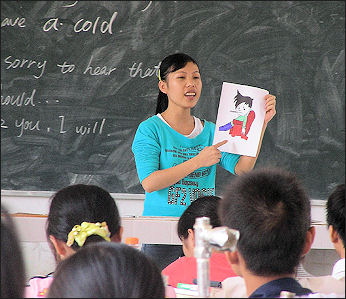

student teacher In China, there are six years of elementary school, three years of middle school, and three years of high school. There is an exam at the end of middle school to decide who attends high school. Only 30 percent of middle school students go on to high school.

According to China’s 2020 census and the National Bureau of Statistics of China: . the average years of schooling for people aged 15 and above increased from 9.08 years in 2010 to 9.91 years in 2020, and the illiteracy rate dropped from 4.08 percent to 2.67 percent in the same period. [Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China, May 11, 2021]

Primary and general secondary school students pay a nominal tuition fee. A typical school has few academic and athletic facilities other than a chalkboard, some desks, chairs and a Chinese flag and courtyard where children play. Better schools have a dirt soccer field. Few schools have air conditioning or heating. In the winter, teachers and students are often bundled up in heavy coats and gloves in the classrooms, their breath forming clouds.

Students are swamped with after school classes: music lesson, English, art and martial arts. All these activities are very competitive and rank students. English is graded on five levels.; piano-playing, 10. More than half of preteens take outside lessons. When parents are asked why they enroll their children in such classes the most often heard answer is “to raise the child’s future competitiveness.” When students are studying for major exams, parents switch television on mute so they can study better.

Students try to stay on their teachers good side, following the proverb: “A person who stands under someone else’s roof must bow his head,” If a kid is bullied and his parents are politically influentially they can pressure to have the bully transferred to another school. There are also stories of students getting into schools without taking entrance exams because their parents had a cousin who knew someone in the education bureau.

Pictures of Sun Yat-sen, Mao Zedong and Zhou Enlai, hang on the walls of classrooms. Above the playing fields at schools are signs that say things like “Education Changes Fate” and “Wisdom Leads You to Glory.” The top two school rules are: 1) love the motherland; 2) “Cherish the honor of the group.” The use of instructional technology in China's classrooms is often inadequate. Many schools, particularly in rural area, still rely on blackboard and chalk as their major instructional media

Websites and Films About Schools in China

Good Websites and Sources: School Life in Beijing bvs-os.de/eigenes/china ; Life in New China whatkidscando.org ; Scenes from Primary School Life radio86.co.uk/china-insight/china-perspective/one-mans-china School Life Video YouTube ; Precious Children PBS Show pbs.org/kcts/preciouschildren ; China Education Blog chinaeducationblog.com

See Separate Articles:CHINESE SCHOOLS Factsanddetails.com/China ; CHILD REARING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; LITTLE EMPERORS AND MIDDLE CLASS KIDS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; VILLAGE SCHOOLS IN 19TH CENTURY CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SCHOOL CURRICULUM IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PROBLEMS AT CHINESE SCHOOLS: CHEATING, EXPLOSIONS AND MYOPIA factsanddetails.com ; TEACHERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PRESCHOOLS AND KINDERGARTEN IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; PRIMARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com THE GAOKAO: THE CHINESE UNIVERSITY ENTRANCE EXAM factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources on Education in China : History of Education System in China math.ksu.edu ; Center on Chinese Education at Columbia University’s Teacher’s College tc.columbia.edu ; China Today on Chinese Schools chinatoday.com ; China Education Blog chinaeducationblog.com ; Wikipedia article on Chinese Education Wikipedia ; China Education and Research Network (Chinese Government Site) edu.cn/english ; China Education and Research Network Statistics edu.cn/HomePage/english/statistics ; Busy Kids chinadaily.com.cn ; Modern Chinese Literature and Culture (MCLC) Education Bibliography mclc.osu.edu ; Chinatown Connection chinatownconnection.com ; Education in the 1980s cis.yale.edu ; China Research Paper Search china-research-papers.com

The novel “Triple Door” by Han Han offers insightful description of Chinese schools but it hasn't been translated into English. ‘Village Middle School’ a documentary by Tammy Cheung ( visiblerecord.com is a fly-on-the-wall documentary about the life in a rural school.

“ Senior Year “ (2005), a film by Zhao Hao, is an in-depth examination of how a class of teenagers prepares for the national college entrance exams in China. When it comes to anxiety about how the U.S compares with other nations, there’s always plenty to go around. But for a real wake-up call, nothing can compare to Zhou Hao’s Senior Year, an in-depth examination of how a class of teenagers prepares for the national college entrance exams that will determine their destinies. Faced with mountains of memorization and rigid behavioral standards, most buckle down, but some rebel and some simply crumble under the pressure. Zhou brings tenderness, humor, and quiet outrage to this rare, behind-the-scenes look at China’s educational system.

“” The Village Elementary “ (“ Changchuan cun xiao “) by new director Huang Mei is a deceptively simple film about rural education and poverty. Huang’s honesty, her respect for her subjects,including a charismatically intellectual, politically aware, but sadly frustrated Sichuanese elementary teacher, gives the film a dirt-poor lyricism that tightly binds the minute details of individual lives to larger issues of political powerlessness and economic dependence.”

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: School Life” “Studying in China: A Practical Handbook for Students” by Patrick McAloon Amazon.com; “Other Rivers: A Chinese Education” by Peter Hessler Amazon.com; “Educating Young Giants: What Kids Learn (And Don’t Learn) in China and America” by N. Pine (2012) Amazon.com; Little Soldiers: An American Boy, a Chinese School, and the Global Race to Achieve by Lenora Chu, Emily Woo Zeller, et al. Amazon.com; “Children’s Literature and Transnational Knowledge in Modern China: Education, Religion, and Childhood” by Shih-Wen Sue Chen Amazon.com; “Governing Educational Desire: Culture, Politics, and Schooling in China” by Andrew B. Kipnis Amazon.com; “No School Left Behind” by Wei Gao and Xianwei Liu (2023) Amazon.com ; Preschool: “Preschool in Three Cultures Revisited: China, Japan, and the United States” by Joseph Tobin, Yeh Hsueh, et al. Amazon.com; “Embracing the New Two-Child Policy Era: Challenge and Countermeasures of Early Care and Education in China”by Xiumin Hong, Wenting Zhu, et al. (2022) Amazon.com; Cram Schools: “The Fruits of Opportunism: Noncompliance and the Evolution of China's Supplemental Education Industry” by Le Lin Amazon.com; “Demand for Private Supplementary Tutoring in China: Parents' Decision-Making” by Junyan Liu Amazon.com; Vocational Education: “Class Work: Vocational Schools and China's Urban Youth” by Terry Woronov Amazon.com; “Improving Competitiveness through Human Resource Development in China: The Role of Vocational Education” by Min Min and Ying Zhu Amazon.com

School Day and School Year in China

The academic year in China runs from September to July and is comprised of a fall semester and a spring semester. Students have classes five days a week with much homework assigned over the weekend.

The main holidays are 1) around May Day on May 1st, in which Chinese get three work days off; 2) the Golden Week around National Day on October 1st; 2) and two or more weeks around Spring Festival (late January or early February). Summer vacation usually lasts from early or mid July to late August.

School begins around 7:30 with a flag raising ceremony and a lecture from the principal who speaks through a bullhorn. Describing the first day of school in a small town school, Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “The loudspeakers crackle, and music came on for the flag-raising. The older children, wearing the red kerchiefs of the Young Pioneers, marched in place while the national anthem played."

Children typically go to school from 7:00am to 4:00pm. Elementary school begins at 7:30am. They study mathematics, reading, writing and propaganda, and often write on thin, brittle paper that feels like onion skin and glows if held up to the light. During recess children do calisthenics and relaxation exercises that consist of pressing two finger on one's eyes, nose or cheeks.

Middle class children fill the hours after school with homework, music lesson and other enrichment programs. English classes and math Olympics are popular. Parents spend sizable chunks of money on classes at computer schools and language academies. Children often have lots of homework, which they often do in copybooks in front of their parents.

Calvin Henrick wrote in the Boston Globe, “Medfield social studies teacher Richard DeSorgher, who spent six weeks in Bengbu, said the differences between the two systems are stark. He said students in China spend long hours at school, and extra time being tutored on nights and weekends for college entrance exams. Class sizes of up to 60 students mean rote learning is common, he said. DeSorgher said he asked a Chinese-born student living in Medfield for advice before the trip. “He said, “Make it fun. The more you can make it fun, the more they’ll want to continue to learn English.” So I went over there armed with a ton of American candy."I think I was kind of an oddity there," DeSorgher added. “I put them in groups, I had them standing and sitting. It was just very different, I think." [Source: Calvin Henrick, Boston Globe, March 20, 2011]

Languages and Schools in China

The teaching language in China is Putonghua, (Mandarin, Standard Chinese). Occasionally, local dialects are used as the teaching language in minority areas; however, the teaching of Mandarin Chinese is strictly enforced and is mostly used alongside local minority languages. Languages in which classes are taught include , Yue (Cantonese), Wu (Shanghaiese), Minbei (Fuzhou), Minnan (Hokkien-Taiwanese), Xiang, Gan, Hakka dialects. In recent years there has been a movement to have all classes in schools in Putonghua.

Chinese is replacing the languages of minorities with Mandarin Chinese as the main teaching medium in schools despite the existence of laws aimed at preserving the languages of minorities. In October 2010, at least 1,000 ethnic Tibetan students in the town on Tongrem (Rebkong) in Qinghai Province protested curbs against the use of the Tibetan language. The protests spread to other towns in northwestern China, and attracted not university students but also high school students angry over plans to scrap the two language system and make Chinese the only instruction in school, London-based Free Tibet rights said. [Source: AFP, Reuters, South China Morning Post, October 22, 2010]

See Separate Articles REPRESSION IN XINJIANG AND DISCRIMINATION AGAINST UYGHURS factsanddetails.com ; EDUCATION IN TIBET factsanddetails.com

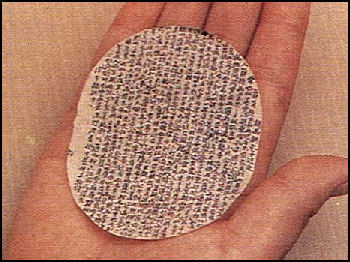

Exam cells at a school for mandarins

School Costs in China

Parents generally have to pay fees for books and uniforms, which are required at most schools. Often they also have to pay for things like electricity, paper, snacks and even report cards. In Beijing, parents have to dish out $20 or more a month for kindergarten. Often the fees add up to several hundred dollars a year. Many rural families can't afford these fees nor can they afford to lose the help of their children in the fields.

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: “ Although the law says the nine-year compulsory education should be free for all children, schools, often driven by economic necessity, ask parents to pay many fees, such as examination paper fees, school construction fees, water fees, and after-school coaching fees. Sometimes due to the high fees charged by schools, rural parents have to pull their children out of school (Lin 1999). [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

Secondary students have to pay a long list of fees, including those for tuition, dormitory rooms, textbooks, and computer access. The fees often are between $200 and $300 a year and are often more than what rural farmers make in a year. Students whose families are behind on their payments are often scolded by their teachers in front of the other students in class. Teachers in turn are pressured by administrators to collect. Those that don’t collect have money docked from their salary.

Rural families often make great sacrifices to send their children to school. The children in turn feel a lot of pressure to perform well, get good jobs and provide for the parents and relatives that made so many sacrifices.

Chinese families spend more on education than anything else except housing. Education is a huge growth industry. Between 2002 and 2005 the market for courses, books and materials more than doubled to $90 billion.

In the mid 2000s, tuition fees were waved for 150 million rural students as part of an effort to narrow the standard-of-living gap between the rich coastal areas and the impoverished countryside. Students became exempt from tuition and incidental fees for their nine-year compulsory education beginning in the spring of 2007. The effort costs the Chinese government about $2 billion per year

Exams, Report Cards and Memorization in Chinese Schools

Students must memorize vast amounts of information to pass major tests, with the biggest determining factor in who attends elite universities and who does not being the “gaokao”, China’s grueling, ultra-competitive university entrance exam. Chinese spend much of their childhood memorizing and writing characters. By the time a student is 15 he or she has spent four or five hours a day over nine years learning to write a minimum of 3,000 characters.

a high school

Stephen Wong wrote in the Asia Times, “It's possible that no other country has as many exams as China. From school admissions and job recruitment to promotion in the civil service, exams are an inseparable part of Chinese life. Incomplete statistics show that there are 200 government-organized nationwide examinations and that nearly 40 million people take national tests each year. The number would be much bigger if local-level tests were included on the list. [Source:Stephen Wong Asia Times, August 22, 2009]

There is a strong emphasis on studying and academics over sports. In many school less than two hours a week is devoted to sports. A Stanford University math professor who studied the math curricula in East Asia told the Los Angeles Times. “There is a very small body of factual mathematics that students need to learn but they need to learn it really, rally well.

Elementary school report cards are 30 pages long. On them are measurements of weight, height, eyesight, hearing, lung capacity accompanied by information on where one fits in with the national average. Teachers give grades, but parents and other students are encouraged to add their assessments, usually pointing out some fault or weakness. On one page there are blank faces where students are expected to evaluate themselves with smiley or frowning faces for things like “takes care of himself” and “cherishes the fruits of physical labor.” A typical teacher evaluation goes: “Everybody loves you. Your thinking is very nimble and the teacher and the other students all admire you. But only if cleverness is combined with hard work will you have improvement.”[Source: Peter Hessler, The New Yorker, March 31, 2008]

Silly School Rules in China

All the students at Luolang Elementary School, a yellow-and-orange concrete structure off a winding mountain road in Huangping county in southern China, know the key rules: Do not run in the halls. Take your seat before the bell rings. Raise your hand to ask a question...and salute all cars when they pass by. Education officials were sharply criticized when news of the rule found its way to the Internet. This is just pitiful, wrote one in a post last year. Only inept officials would burden children with such a requirement rather than install speed bumps, others insisted. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, October 25, 2009]

Morning exercises at an elementary school

Sharon Lafraniere wrote in the New York Times, “Education officials say compliance is strictly voluntary. Asked whether they follow it, elementary students here tend to burst into nervous giggles. The rule’s purpose is twofold: to keep children safer on the county’s corkscrew mountain roads and to teach manners. Nearly 30 schools are located along roads without sidewalks or speed bumps. Signs posting speed limits are few and far between; virtually no signs indicate a school nearby.

“Long Guoping, deputy chief of the county education bureau, said those measures were coming. Little by little, the government is installing them, he said. In the meantime, the salute might avoid some accidents, he said. It allows the drivers to notice the children and the children to notice the drivers.”

“Luo Rongmei, who teaches first grade at Luolang Elementary School, is all for it. Since they started saluting there has not been one traffic accident, she said, as the students ran and shouted in the yard. Guo Yuozhang, 63, whose grandson attends the Luolang school, said he was more ambivalent. If the cars come from one direction, that is not too bad, said. Cars coming in both directions is a bigger hassle. Sometimes they are just turning in circles and they get kind of stuck, he said. He spun around to illustrate the point, smiling slyly.”

School Files in China

Everyone in China who has been to high school has a file — a sealed Manila envelope stamped top secret, containing grades, test results, evaluations by fellow students and teachers, and if they have one a Communist Party application and proof of a college degree. Sharon Lafraniere wrote in New York Times, “The files are irreplaceable histories of achievement and failure, the starting point for potential employers, government officials and others judging an individual’s worth. Often keys to the future, they are locked tight in government, school or workplace cabinets to eliminate any chance they might vanish. [Source: Sharon Lafraniere, New York Times, July 26, 2009]

The files are crucial for getting any kind of good job. Heaven forbid if they ever get lost . But that is exactly what happened to Xue Longlong and 10 others, all 2006 college graduates with exemplary records, all from poor families living in Wubu, a gritty north-central town on the wide banks of the Yellow River. With the Manila folders went their futures, they say.

“While not quite as important as in Communist China’s early days,” Lafraniere wrote , “when it was a powerful tool of social control, the file, called a dangan, is an absolute requirement for state employment and a means to bolster a candidate’s chances for some private-sector jobs, labor experts say. Because documents are collected over several years and signed by many people, they are virtually impossible to replicate.”

“Today, Xue, who had hoped to work at a state-owned oil company, sells real estate door to door, a step up from past jobs passing out leaflets and serving drinks at an Internet cafe. Wang Yong, who aspired to be a teacher or a bank officer, works odd jobs. Wang Jindong, who had a shot at a job at a state chemical firm, is a construction day laborer, earning less than $10 a day...If you don’t have it, just forget it! Wang Jindong, now 27, said of his file. No matter how capable you are, they will not hire you. Their first reaction is that you are a crook.”

Learning in Chinese Schools

students playing basketball Children have traditionally learned by rote, memorizing material without asking questions. Many topics are banned. A great amount of time is spent learning numerous Chinese characters, which are basically memorized.

There are often 40 to 50 students in a classroom and can be up to 60 kids in a class. Students sit in rows and are often expected to sit upright with serious expressions on their faces. The school day often begins with the teacher tapping her pointer on the desk and the students rising in unison and dutifully shouting, “Hello, teacher!” The teacher them signals every everyone to sit down and leads them like a conductor as they shout out memorization drills. Having some many students encourages rote learning rather than student-driven activities and discussions. One Chinese educator told the New York Times, “You let them free, but it’s such a big group, its hard to get them back. It’s a real challenge how to get the balance right.”

Ting Ni wrote in the World Education Encyclopedia: While some subjects (such as English, geometry, or algebra) provide more opportunities for students to practice or to drill, the structure of the lessons, their pace, and the nature of questioning are all determined by the teachers, who control the nature of classroom interactions. The most common experience for students is to go through the forty-five minute period without talking once, without being called on individually, or without asking a question. Students are taught that important knowledge comes from teachers and textbooks; that learning involves listening, thinking, and silent practice; and that the knowledge espoused by teachers and textbooks is not to be challenged, despite the lack of connection between course material and the immediate lives of the students. [Source: Ting Ni, World Education Encyclopedia, Gale Group Inc., 2001]

A fashion designer told the Washington Post, “Chinese people are educated to be the same.” Schools emphasize group activities and discipline and repeating what one has been taught and play down individualism and critical thinking. Class activities generally features students dressed exactly the same — boys in blue tracks suits and girls in red ones — performing the same kind of banner-waving drills or marches.

Reforms include using a wide variety of textbooks, removing dense passages from textbooks, reducing class size, using groups and partners and more hands-on learning, encouraging students to figure out problems themselves and emphasizing project-based learning. Private schools are at the forefront of these reforms. They often have many clubs and activities outside of school. The main thing that holds these kinds of reforms back is that there are not enough teachers trained in such methods.

Problems with Learning in China

The educational system stresses obedience and rote learning over creativity. Children are taught to be obedient and conform in accordance with an old Chinese proverb that goes: “The bird that flies out its flock is the first one targeted by hunters.” When children learn to write they began with specific strokes and copy them over rand over. They then combines these into characters and copy them over and over.

Peter Hessler wrote in The New Yorker, “Everything revolves around repetition and memorization, which works beautifully for math. But other subjects often developed into scattered facts that careen between traditional and modern, Chinese and foreign. I was amazed by the stuff Wei Kia learned — the most incredible assortment of de-systemized knowledge that had even been crammed into a child in the forth grade.” [Source: Peter Hessler, The New Yorker, March 31, 2008]

“In English he memorized odd vocabulary lists: “Spaceship,” “pizza,” “astronaut.” A textbook called “Environmental and Sustainable Development” must have spawned from some collaboration with a foreign N.G.O. It taught the “the five R’s” — Reduce, Reevaluate, Reuse, Recycle, Rescue Wildlife — which make no sense when translated into a language with no alphabet. Fifth graders memorized pages of instructions for Microsoft Front Page XP.”

Among the things that the students learned were that Google was started by a brother and sister in America, that the Buddha in Leshan was 70 meters tall. Wei didn’t know what a province was, thought San Francisco was in China and thought the current leader of China was Mao Zedong, Among the things he did for homework was recite the Tao te Ching.”

A proposal to reform the curriculum in Chinese schools in 2013 suggested reducing the value of the English portion of the multisubject test and increasing the value of the Chinese and social or natural sciences (students can choose) parts. Adam Minter of Bloomberg wrote: Perhaps even more significant, the English section would also put a stronger emphasis on practical listening skills, rather than grammar and reading. Though the proposal is local, the fact that it’s happening in China’s capital is a signal that other schools can — and probably should — consider similar reforms.[Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, October 29, 2013]

Homework-Doing Robots and Classrooms Facial Recognition

Shenzhen middle school In 2019, a big deal was made about a high school who used a robot to do her homework. The New York Times reported: Some would say she cheated. Others would say she found an efficient way to finish her tedious assignment and ought to be applauded for her initiative. The debate lit up Chinese social media after the Qianjiang Evening News reported that a teenage girl bought a robot that mimicked her handwriting. Instead of having to manually copy phrases or selections from a textbook dozens of times, a repetitive task common in learning Chinese, she could just teach the robot to do it for her. [Source: Daniel Victor and Tiffany May, New York Times January 21, 2019]

“On Weibo, a popular social media platform, commenters who had suffered through endless hours of similar homework themselves were split, though most appeared to be sympathetic or even impressed. “Give her a break. How meaningful is copying anyway?” one commenter asked. “The difference between humans and other animals is that they know how to make and use tools,” another reasoned. “This young lady already knows how to do this.”

“The Chinese newspaper reported that the girl had spent about 800 yuan, or $120, that she had saved from Lunar New Year presents to buy the robot. She finished a slew of text-copying assignments in two days, much faster than her mother expected, the newspaper reported. The mother discovered — and then smashed — the machine while cleaning the girl’s room, according to the article. Such technology typically uses robotics to drag a pen across an anchored piece of paper. Some of the products feature pre-loaded handwriting styles, while some allow users to digitize and copy their own handwriting.

In 2018, a network of surveillance cameras backed by facial-recognition technology was installed into every classroom at a high school in Hangzhou, Zhejiang Province. Sup China reported: Praised by the school’s principal as “insightful eyes,” the cameras are capable of capturing and analyzing students’ body movements and facial expressions during class, offering teachers real-time feedback on how attentive their students are. According to Sina News, with the newly installed cameras that can tell who might be discreetly taking a nap, students at Hangzhou No. 11 High School are more focused in class than ever. “Before the introduction of these cameras, I sometimes took naps or did other stuff while having classes that I don’t like,” one student told reporters, adding that his classmates all felt the same. “But now, I always feel there are mysterious eyes staring at me, so I don’t dare do things that are unrelated to class anymore.” [Source: Jiayun Feng: Sup China, May 16, 2018]

“Based on data collected by these cameras, a system automatically creates a report at the end of each day that includes information about how many students look neutral, happy, sad, angry, scared, abhorrent, or surprised. “This system not only motivates students to study harder, but it also supervises the quality of teaching,” said the school’s vice principal. On the social media platform Weibo, many people expressed disgust at the measure, criticizing it as “inhumane” and accusing the school of going too far to monitor students’ facial expressions. “Big boss is watching you,” one commenter wrote. In a reference to a recent statement by the U.S. Embassy in China, in which the U.S. government called Chinese “political correctness” “Orwellian nonsense,” another internet user wrote, “This looks like Orwellian education.”

Cram Schools in China

Many school-age children in China attend cram schools to augment their education mainly with the goal of doing well on tests like the gaokao, the university-entrance exam. According to the Chinese Ministry of Education the after-school tutoring is a lucrative business sector that has grown rapidly over the past few years as the country’s education system became increasingly cutthroat. By some estimates it is worth $120 billion a year. So much money is spent by China’s middle class on cram school education that economists say it deprived other economic sectors of money. [Source: SupChina, June 16, 2021]

According to the South China Morning Post in 2019: Beijing-based New Oriental and TAL Education Group, the two largest listed education companies, both reported accelerating double-digit revenue growth in the first half of this year. New Oriental said total student enrollment in academic subject tutoring and test preparation courses increased by 44.9 per cent year-over-year to 2.06 million for the quarter ended May 31. TAL, meanwhile, said total student enrolment surged by 88.7 per cent from a year earlier to nearly 2 million students in the same quarter. [Source: Jane Cai, South China Morning Post, October 16, 2018]

According to a survey of nearly 52,000 parents across the nation, most of them middle class, conducted by website Sina.com in November 2017, spending on education accounted for an average 20 per cent of household income. About 90 per cent of preschool children and 81 per cent of K12 students, aged six to 18, have attended tutoring courses. Families with preschoolers spent an average 26 per cent of their income on education, while those with K12 children had education-related outlays of 20 per cent of their income. Of all the respondents, about 61 per cent said they had plans to send their children to study overseas.

According to Sup China: “Concerned about the market’s unchecked growth, which was largely fueled by exploitation of parental paranoia and problematic tactics like false ads and misleading campaigns, Chinese regulators have introduced a plethora of restrictions, including caps on fees that firms can charge and time limits on after-school programs. In April 2021, the education authorities of Beijing’s municipal government hit four Chinese education giants with fines for deceptive pricing and misleading marketing tactics, following a previous mandate ordering local tutoring schools to put a temporary halt to offline teaching. A month later, during a meeting on health and education, Xí Jìnpíng lashed out at the sector’s “disorderly development” and vowed to rectify it. In may, rumors surfaced that China was preparing to ban private education companies from going public, which led to a major sell-off of education shares. [Source: Jiayun Feng, SupChina, June 16, 2021]

Cram School Life in China

Cheat sheet for civil service exam Jane Cai wrote in the South China Morning Post: “It’s a Sunday afternoon, and Amy Jiang is rushing through a packed lunch with her seven-year-old daughter outside her classroom in a shabby building in Beijing. They are on a break between two lessons, each two hours, given by an after-school tutoring company. Like millions of middle-class parents on the mainland, Jiang, a 35-year-old engineer, spends most of her weekends attending tutoring sessions with her child. “I have to be here,” Jiang said. “Some topics are too advanced for kids to understand, such as permutations and combinations in maths, and classical Chinese.” [Source: Jane Cai, South China Morning Post, October 16, 2018]

Studying a wider range of subjects in more depth than the public school syllabus requires and getting a head start by studying topics before they are covered in school have become common tactics used by parents trying to help their children compete in a challenging educational environment in China. “Chinese parents, especially the middle class, understand it’s hard to climb the ladder of success if children from ordinary families do not possess degrees from a good university,” Hu Xingdou, an independent economist, said. “Amid fear and anxiety, the middle class are pushing their children to study hard and are willing to save every penny to invest in education.”

Jiang is from a rural part of northern Shanxi province, but she graduated from a top university in Beijing. Her annual income of 100,000 yuan (US$14,500) is twice that of the average urban worker’s in the city.That makes her a member of China’s so-called middle class of three million, with a yearly salary of between US$3,650 and US$36,500, according to the World Bank definition.

She attributes this success to the education she received. So now, Jiang spends 12,000 yuan a year on maths lessons for her daughter, 12,000 yuan on Chinese, and 25,000 yuan on English. On top of that, she has spent about 50,000 yuan on dancing and piano lessons for Jiejie, and 20,000 yuan on an overseas trip to help the child “gain some international experience”. Education expenses account for about 30 per cent of her household income, she said. “Don’t call me middle class – my husband and I have never bought any clothes priced higher than 100 yuan since we had Jiejie,” she said. “We’re saving every penny for our daughter, as education provides the only channel in China for ordinary people like me to secure a decent life in the future.”

China Cracksdown on Homework and Cram School Pressures

1935 Chinese education film In October 2021, the Chinese government passed an education law that seeks to cut the 'twin pressures' of homework and off-site tutoring in core subjects. Reuters reported: Details of the law's passing were reported in Chinese state media. It says the legislation makes local governments responsible for ensuring that pressure on children is reduced. The law asks parents to arrange their children's time to account for reasonable rest and exercise, and to avoid them overusing the internet. [Source: Reuters, October 23, 2021]

The BBC reported: “The law received a mixed reaction on social media site Weibo, with some users praising the drive for good parenting while others questioned whether local authorities or the parents themselves would be up to the task. "I work 996 [from 9am to 9pm, six days a week], and when I come home at night I still need to carry out family education?" one user asked, quoted by the South China Morning Post newspaper. "You can't exploit the workers and still ask them to have children." [Source: BBC, October 23, 2021]

In August 2021, China banned written exams for six and seven year olds. Officials warned at the time that students' physical and mental health was being harmed. In July, Beijing stripped online tutoring firms operating in the country of the ability to make a profit from teaching core subjects. China's parliament is also considering legislation that would punish parents if their children exhibit what it regards as "very bad behaviour" or commit crimes. In recent months, the education ministry has limited gaming hours for minors, allowing them to play online for one hour on Friday, Saturday and Sunday only.

In 2019, Zhejiang province published draft guideline proposing students go to bed at a decent hour — 9:00pm for primary school students and 10:00pm for middle school students — even if they hadn’t finished their homework. According to AFP: “The proposal has touched a nerve in China, with some parents concerned that reducing the homework burden will put children at a disadvantage when preparing for the highly-competitive college entrance exam. [Source: Helen Roxburgh and Qian Ye, AFP, October 31, 2019]

Harvard MBA Who Did Poorly in Chinese Schools

Raymond Li of the South China Morning Post interviewed Yu Zhibo, who was a “mainland parents fear, an academic failure for a child. Now 29, the Harvard MBA holder explains how moving to the United States to study let him explore his individuality and find his way, things he said he could not have done at home.” How badly did you do at school? Li asked. Yu said, “Here are two examples: when I was nine, I had to repeat grade three because I did so poorly in my studies after my family moved from Shanghai to Chengdu. Then, when I was at secondary school, my overall scores put me third from the bottom in my class.” [Source: Raymond Li, South China Morning Post, January 16, 2011]

Was that because you did not study hard enough? “I actually studied harder than any other classmate. In order to help me catch up in maths, physics and chemistry, my parents once hired threeafter-school teachers. But every time I came across a maths formula or the periodic table of elements, I told myself I would not want to see them again in my life. I liked geology and history and excelled at sports. But that counted for little in the way people looked at you.”

How did you feel at the time? “Some of my classmates made fun of me as someone with a well-developed body but no brain. The pressure to perform well in science subjects in order to enter a university became so intense that I felt I could hardly breathe. I was so depressed that I was loath to study and wanted to run away.”

What prompted you to go to the US? “It was a summer trip in 1996; I had the chance to live with an ordinary American family in Oregon for three weeks. What struck me most were small details in daily life. For example, I was driving with the mother one day when she stopped at a stop sign, even though there was no pedestrian in sight. Another time, she told me to pick up a Coke can I threw on the ground and reminded me it wasn't the right thing to do. I was very impressed and wondered how someone from a blue-collar family with not much education could care so much about the environment. Later I realized it must be the way people were taught. On the other hand, nobody asked how I'd scored in maths or chemistry and I got the chance to play a lot. I had such a pleasant three weeks that two years later, I enrolled in an Oregon high school.”

What were the highlights in your studies and work in the U.S.” “I spent three months working on an Oregon farm after graduating from high school. There I had my first taste of the thrill and hardship of an American farmer. Inspired by what my father did in 2002 to promote Chinese literature studies via an international forum, I launched a Greater China Supply Chain Forum at Michigan State University. In 2004, I got my first job at Dell headquarters in Austin, Texas, and went on to study at Harvard. The Harvard offer did not come easy as I had to sit the GMAT three times. Now I'm a senior assistant to Yang Yuanqing, chief executive of Lenovo. The most important thing about studying in the US was that I felt I could decide what I wanted and what I enjoyed.

Advise from Harvard MBA Who Did Poorly in Chinese Schools

Raymond Li of the South China Morning Post asked Harvard MBA Yu Zhibo: You have written a book referring to yourself as a boy who lost out at the starting line. Is there a "starting line" in a person's career or life and once you lose out at the beginning you lose all the way? “I do believe there is such a line, but what I don't share with many mainland parents is that there is more than one starting line in your life. For example, you will have a starting line at primary school and another one at secondary school, and even when you are 40 or 50. It depends how you look at your life. I didn't do well at primary and secondary schools, but it doesn't mean I will be at the losing end all my life. Every time you are back on your feet, it's a new starting line.” [Source: Raymond Li, South China Morning Post, January 16, 2011]

What would you tell mainland parents who are anxious about their children's future? “Do not give the children pressure, because it might force them to rebel or go to extremes. Parents should back off a bit to give a good analysis of the strengths and weaknesses of their children in order to nurture what they are good at, instead of forcing them to compete with others in what they are not good at. Secondly, parents should realise that they would take greater comfort in seeing their children do what they enjoy.”

Some say mainland schools are like bird cages. What's your opinion? “I am even more critical than that. I see the mainland education system as a prison. It's like students are being locked up in a jail by their teachers and parents and made to do what they want them to do. Schools are pretty much controlled by the authorities and the public has little say in how they are run. I never felt I was studying for myself, and I believe I'm not the only one who feels this way. It speaks volumes when we see students burn their textbooks upon graduation.”

In response to Uy’s comments Andrew Field, a Shanghai-based professor wrote, “It's nice to see alternative points of view from Chinese people about education in Shanghai or other parts of China. Yu Zhibo's responses are interesting, but I think he's off target. Yu tells Mainland parents to "not give their children pressure" and let them excel in what they are already good at. This strikes me as pretty weak advice, since it isn't the parents alone, but the entire system that puts the pressure on the kids. As I've already mentioned in previous posts, my daughter is in first grade in a local school here in Shanghai. We get phone calls on a regular basis from my daughter's teachers about her performance. There's a lot of social pressure as well, and the teachers themselves are under tremendous pressure to enhance their students' performance. So telling parents to take it easy on their kids is not a real solution. Funny advice from a Harvard MBA...The only solution to changing China's current educational system is to reform the system from the top down so that it doesn't emphasize rote learning and test taking as much, but as anybody here knows, that is not likely to happen any time soon.

Image Sources: Wiki Commons: Nolls China website ; ; Columbia University; Beifan.com ; University of Washington; Bucklin archives

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated August 2022