CHINESE MEGACITIES

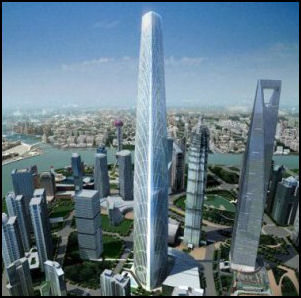

Shanghai skyscraper that wasn't built

The urban population of China is expected to rise to 80 percent or 90 percent of the entire population in coming decades. George Yeo, Singapore’s foreign minister, wrote in Global Viewpoint, “China is urbanizing at a speed and scale never seen before in human history...Recognizing the need to conserve land and energy, the Chinese are now embarked on a stupendous effort to build megacities, each accommodating tens of millions of people, each with the population of a small country. And these will not be urban conurbations like Mexico City or Lagos growing higgledy-piggledly but cities’ with planned urban infrastructure.

The McKinsey Global Institute estimates that at least 15 megacities with 25 million residents — each with the population of a major country — and 11 city-clusters, each with a combined population of more than 60 million — will come into existence. Because so much land is owned by the state the Chinese government will be able determine how these cities will be shaped with industrial parks, high-speed trains and areas of skyscrapers.

The largest cities in mainland China by population of urban area:

1) Shanghai — 26,917,322 in 2020; 20,217,748 in 2010

2) Beijing — 20,381,745 in 2020; 16,704,306 in 2010

3) Chongqing — 15,773,658 in 2020; 6,263,790 in 2010

4) Tianjin — 13,552,359 in 2020; 9,583,277 in 2010

5) Guangzhou in Guangdong — 13,238,590 in 2020; 10,641,408 in 2010

6) Shenzhen in Guangdong — 12,313,714 in 2020; 10,358,381 in 2010

7) Chengdu in Sichuan — 9,104,865 in 2020; 7,791,692 in 2010 [Source: Wikipedia]

See Separate Articles: URBANIZATION AND URBAN POPULATION OF CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HUKOU (RESIDENCY CARDS) factsanddetails.com CITIES IN CHINA AND THEIR RAPID RISE factsanddetails.com ; MASS URBANIZATION IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN DEVELOPMENT AND DESTRUCTION OF THE OLD NEIGHBORHOODS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOME DEMOLITIONS AND EVICTIONS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; HOMELESS PEOPLE AND URBAN POVERTY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com

Websites and Sources: Wikipedia article Wikipedia

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Shenzhen Experiment: The Story of China’s Instant City: by Juan Du Amazon.com; “China’s Urban Revolution: Understanding Chinese Eco-Cities” by Austin Williams Amazon.com; “Green Development Model of China’s Small and Medium-sized Cities” by Xuefeng Li and Xuke Liu Amazon.com; Urban Life in China: “Leisure and Power in Urban China: Everyday Life in a Chinese City” by Unn Målfrid Rolandsen Amazon.com; “Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration” by Kam Wing Chan Amazon.com; “China's Housing Middle Class: Changing Urban Life in Gated Communities” by Beibei Tang Amazon.com “The Specter of "the People": Urban Poverty in Northeast China” by Mun Young Cho Amazon.com; Invisible China: How the Urban-Rural Divide Threatens China’s Rise by Scott Rozelle and Natalie Hell Amazon.com

China to Spend $3.2 Billion Flattening 700 Mountains to Create Mega-city

In December 2012, China's Communist Party announced it was going to flatten 700 mountains to make way for a new super-city near Lanzhou in Gansu Province. AN1 reported: “In what is being dubbed the biggest mountain-moving project in the country's history, the ambitious scheme will see a metropolis created 50 miles from the city of Lanzhou in the northwest of China. Demolishing the desolate mountains in the country's Gansu province will cost developers $3.2 billion pounds, but, according to the state-run newspaper The China Daily, more than seven billion pounds of corporate investment has already been invested, the Daily Mail reports. [Source: ANI, News Track India, December 9, 2012 =]

“The project is the first planned for the country's interior and the fifth of the so-called state-level development zones. The scheme, which was reported in the China Economic Weekly on Tuesday, was given the green light by authorities in August 2012. However, it has raised concerns from environmentalists who point out that Lanzhou which is home to 3.6 million people who work alongside the Yellow River is already considered one of the most polluted places in the world, the report added. =

According to the report, Liu Fuyuan, who previously worked as a high-ranking official at the country's National Development and Reform Commission, told China Economic Weekly that the project was unsuitable because Lanzhou is frequently listed as among China's most chronically water-scarce municipalities. The project is due to start in October 2013 with the first construction to be a new urban district of almost 10 square miles, the report said. Multi-millionaire developer Yan Jiehe's company, China Pacific Construction Group, is in charge of the work and China's second wealthiest man has dismissed suggestions that the project is flawed financially and environmentally, it added. According to the report, a promotional video posted on the Lanzhou new area website shows a digitally-rendered cityscape of gleaming skyscrapers and leafy parks. =

Merging and Expanding Cities and Rural Metropolises in China

Benjamin Haas wrote in The Guardian: “Measuring the population of a city in China is not an exact science. Chinese cities often administer sizeable rural areas beyond the city centre and surrounding suburbs, and the Chinese word for city — shì — is typically used to describe a sub-provincial region. Rolling mountains and hundreds of miles of the Great Wall lie within Beijing’s official boundary, for instance, and nearly all Chinese municipalities contain at least one rural county within the city limits. In one extreme example, Chongqing municipality covers an area almost the size of Austria, but the urban area covers only about a quarter of that, according to Demographia. Analysis shows that while the total population living within the city limits is close to 50 million, only about 7.4 million people live in the urban area. [Source: Benjamin Haas The Guardian, March 20, 2017]

“Another issue is that Chinese cities are growing so large that it has become difficult to determine where one begins and another ends. Guangzhou, formerly known as Canton, has an underground line that snakes into the neighbouring city of Foshan. Does that make it one city or two? The government is currently attempting to tie Beijing with two neighbouring regions, the city of Tianjin and Hebei province, to create the megacity of Jing-Jin-Ji. In a sign of how serious the authorities are about integrating the three regions, the government recently approved a £29bn railway to improve transport links. The resulting megacity will have a combined population of more than 100 million, and cover an area twice the size of South Korea.

China’s Megacities Combining into Megaregions

Richard Macauley wrote in Quartz, “The southwestern Chinese city of Chongqing, by some measures, is one of the largest and fastest-growing cities in the world, with an official population of 29 million—about the same as Saudi Arabia—and unofficial population of 32 million or more. The city center of Chongqing boasts a mere 9 million people, but dozens of satellite districts such as Fuling (population 1 million) and Wanzhou (1.6 million) are each major cities in their own right. In total, Chongqing covers an area the size of Austria, and it’s about to become part of a mega-region that is even larger, part of move in China to create the biggest urban municipalities on Earth. [Source: Richard Macauley, Quartz, May 5, 2014 */]

“Chongqing, for example, will be part of the even larger Chuanyu mega-region, which also includes the major city of Chengdu and 13 cities from Sichuan province. The Capital Economic Zone encompasses Beijing and Tianjin; the Pearl River Delta region includes Guangzhou, Shenzhen, and Hong Kong; and the Yangtze River Delta region is centered around Shanghai. China isn’t alone in the development of mega-regions—greater Tokyo and the Washington, DC-Boston corridor also have similarly huge populations and geographies—but China’s ongoing urbanization and rapid growth is making it something of a laboratory for urban planning on a massive scale. The theoretical appeal of ever-larger municipal areas is that they will create efficiencies in the delivery of services like transport and sanitation, while knitting together a thriving urban ecosystem. */

“The trouble is that China’s mega-cities and mega-regions aren’t being built with an eye toward maximizing the advantages and minimizing the downsides of creating these massive metropolises. Most importantly, the mega-regions are being built around a small number of city centers, many of which are surrounded by concentric circles of commuters and bedroom communities that makes traffic hellish and pollution even worse. “Among the 10 developed and emerging mega-regions in China, only a limited number have exhibited a significant level of polycentricity,” concluded a report by the Lincoln Institute of Land Policy, a US think tank. “Around half of the 10 mega-regions are either dominated by a single major center, or by a limited number of major centers which are located closely to one another.” */

“This is a problem because it ultimately means everyone will want to work in close proximity to the city centers, which causes sky-high property prices and transportation headaches. Size doesn’t always have to be a negative, though. “Mega-cities are a necessary step in the development of urban areas,” Eric Marcuson, a Chongqing-based urban planner at Aecom, told Quartz. “A city is just an urban area with one center, but to increase growth and productivity cities eventually need to encompass more, complimentary centers.” */

“Unfortunately it doesn’t appear that China is following the advice of urban planners like Marcuson. Take Beijing, a city of around 20 million residents with just one main center for commerce and productivity. It is surrounded by concentric ring roads that create heavy traffic, and even its very good subway system is hugely overcrowded. Nevertheless, the Chinese government seems determined to double-down on Beijing, combining it with the city of Tianjin and parts of Hebei province into one huge megalopolis. But as Quartz has reported, While Hebei isn’t likely to attract workers away from Beijing, the other cities in the proposed “Jing-Jin-Ji” region are mostly suburbs, with no real urban centers of their own—precisely the opposite to what the specialists advise. */

China’s Metropolis Clusters

There are at least 19 projects to turn major cities into huge urban conglomerates. Adam Minter of Bloomberg wrote: “The effect could be transformative. For one thing, it will create the world's biggest labor markets, and further urbanize a country that's still more than 35 percent rural. It should boost economic growth and efficiency. And it could help solve a growing dilemma: Many of China's biggest cities have simply reached their geographic and demographic limits. "Adding more density to the cities won't work anymore, " says Alain Bertaud, a senior research scholar at New York University who has consulted in China for decades. The problem, he says, is that those cities are increasingly fragmented. [Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, August 25, 2016]

“Housing in Shanghai and Beijing has become so expensive that non-wealthy residents have been pushed to the furthest reaches of the suburbs, where commuters often face extended waits just to enter a subway station — let alone actually get on a train. The result is a large labor force that can't be put to work by employers, largely defeating the purpose of urbanization.

“There's some precedent for this approach. Long before anyone had heard the term "city cluster, " China's relentless expansion had caused urban areas to start melding into one another. Most notable was the Pearl River Delta, where Guangzhou, Shenzhen, Hong Kong and several smaller cities merged into an informal cluster famous for its manufacturing. The organic nature of that development, though, meant that there was no regional authority to deal with the problems that resulted — the traffic, the pollution, the wasteful subsidized competition between neighbors — and an uneven distribution of social services. China's planners are hoping that the new clusters can reap the advantages of the old ones, but with more order and efficiency.

“That won't be easy. Transportation poses a particular challenge: High-speed rail and subways can move commuters between cities, but the final journey — from station to workplace or home — is much harder. (Bertaud notes that China's urban planners "are very interested in self-driving cars.") Another pressing task will be getting local governments to stop using land sales to finance infrastructure and services. Doing so induces further sprawl, raises the cost of public works and leads to the ghost cities — or, at least, ghost neighborhoods — that plague China's urban areas. New regional authorities will also be needed to manage clusters that will span thousands of square miles and tens of millions of people. All this will be arduous. But with the benefit of decades, China's city clusters could become key economic engines — and, maybe, a model for how cities around the world can keep growing.

Yangtze Delta Cluster

Adam Minter of Bloomberg wrote: By any measure, Shanghai is one of the world's biggest cities. It's home to more than 24 million people. Its subway system is the longest ever built, extending to its rural limits. Crowds are so thick that burly "shovers" get paid to help pack the trains. Now the local government is saying enough is enough: Documents released this week reveal that Shanghai intends to admit a mere 800,000 new residents over the next 24 years, on its way to becoming an "excellent global city." [Source: Adam Minter, Bloomberg, August 25, 2016]

“A population cap on one of China's most dynamic locales may seem impractical. But the government is actually thinking bigger: The plan envisions Shanghai as the high-end hub at the center of a massive "city cluster" comprising 30 urban areas — with a staggering total population of 50 million. That might sound preposterous. But the Yangtze Delta Cluster, as it's known, is one of at least 19 such projects in the works. The idea is to use an extensive hub-and-spoke rail system, much of it high-speed, to better integrate China's burgeoning urban areas. The big three clusters — located along the Pearl River, the Yangtze River and the Beijing-Tianjin corridor — will each have 50 million people or more.

In theory, those 50 million people in the Yangtze Delta Cluster will all be within commuting distance of Shanghai, yet they won't need to jam into its over-crowded neighborhoods or rely on its overloaded public services. They'll get the benefits of density, in other words, while spreading out its burdens.

Jing-Jin-Ji — the Beijing Area Supercity

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: The Chinese “government has embarked on an ambitious plan to make Beijing the center of a new supercity of 130 million people. The planned megalopolis, a metropolitan area that would be about six times the size of New York’s, is meant to revamp northern China’s economy and become a laboratory for modern urban growth. “The supercity is the vanguard of economic reform, ” said Liu Gang, a professor at Nankai University in Tianjin who advises local governments on regional development. “It reflects the senior leadership’s views on the need for integration, innovation and environmental protection.” [Source: Ian Johnson, New York Times, July 19, 2015]

“The new region will link the research facilities and creative culture of Beijing with the economic muscle of the port city of Tianjin and the hinterlands of Hebei Province, forcing areas that have never cooperated to work together. In July 2015, the Beijing city government announced its part of the plan, vowing to move much of its bureaucracy, as well as factories and hospitals, to the hinterlands in an effort to offset the city’s strict residency limits, easing congestion, and to spread good-paying jobs into less-developed areas.

“Jing-Jin-Ji, as the region is called (“Jing” for Beijing, “Jin” for Tianjin and “Ji, ” the traditional name for Hebei Province), is meant to help the area catch up to China’s more prosperous economic belts: the Yangtze River Delta around Shanghai and Nanjing in central China, and the Pearl River Delta around Guangzhou and Shenzhen in southern China.

“But the new supercity is intended to be different in scope and conception. It would be spread over 82,000 square miles, about the size of Kansas, and hold a population larger than a third of the United States. And unlike metro areas that have grown up organically, Jing-Jin-Ji would be a very deliberate creation. Its centerpiece: a huge expansion of high-speed rail to bring the major cities within an hour’s commute of each other.

“Beijing is shifting much of its city administration to the Tongzhou suburb, ending the longstanding practice of putting government offices in the old imperial district. The plan has started to drive up property prices in the suburbs, according to local news reports. But several factors are making Jing-Jin-Ji a reality. The most immediate is President Xi Jinping, who laid out an ambitious plan for economic reform in 2013 and has endorsed the region’s integration.

“Wang Jun, a historian of Beijing’s development, said creating the new supercity would require a complete overhaul of how governments operated, including instituting property taxes and allowing local governments to keep them. Only then can these towns become more than feeders to the capital. “But some of the new roads and rails are years from completion. For many people, the creation of the supercity so far has meant ever-longer commutes on gridlocked highways to the capital“This is a huge project and is more complicated than roads and rail, ” he said. “But if it can succeed, it will change the face of northern China.”

Beijing Supercity Transportation, Infrastructure and Economic Zone

Ian Johnson wrote in the New York Times: “The plan calls for eliminating the “beheaded highways” by 2020 and constructing a new subway line. In addition, the plan assigns specific economic roles to the cities: Beijing is to focus on culture and technology. Tianjin will become a research base for manufacturing. Hebei’s role is largely undefined, although the government recently released a catalog of minor industries, such as wholesale textile markets, to be transferred from Beijing to smaller cities.

“Improving the infrastructure, especially high-speed rail, will be critical. According to Zhang Gui, a professor at the Hebei University of Technology, Chinese planners used to follow a rule of thumb they learned from the West: All parts of an urban area should be within 60 miles of each other, or the average amount of highway that can be covered in an hour of driving. Beyond that, people cannot effectively commute.

“High-speed rail, Professor Zhang said, has changed that equation. Chinese trains now easily hit 150 to 185 miles an hour, allowing the urban area to expand. A new line between Beijing and Tianjin cut travel times from three hours to 37 minutes. That train has become so crowded that a second track is being laid.

“Now, high-speed rail is moving toward smaller cities. One line is opening this year between Beijing and Tangshan. Another is linking Beijing with Zhangjiakou, turning the mountain city into a recreational center for the new urban area, as well as a candidate to host the 2022 Winter Olympic Games. “Speed replaces distance, ” Professor Zhang said. “It has radically expanded the scope of what an economic area can be.”

Part of this plan is the Xiongan New Area, a co-ordinated development of the Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region similar to the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone established in the 1980s and the Shanghai Pudong New Area established in the 1990s, according to a circular issued by the Communist Party of China (CPC) Central Committee and the State Council. Located about 100 kilometers (60 miles) south-west of central Beijing in Xiongxian, Rongcheng and Anxin counties and encompassing Baiyangdian, one of the largest freshwater wetlands in North China, it It will cover about 100 square kilometers initially and will be expanded to 200 square kilometers in the mid-term and about 2,000 square kilometers in the long term, according to the official circular. It will operate as a new growth pole for the country’s economy, and also aim to curb urban sprawl, bridge growth disparities and protect ecology.[Source: China Daily, April 19, 2017]

Future City Projects and Model Cities in China

Broadtown Model City

There are a number of “future city” projects currently under construction in China. Jacqui Palumbo of CNN wrote: Rapid urbanization in the country has led to population caps in major metropolises like Beijing and Shanghai. To manage the overflow, officials are funneling money into new satellite cities like Xiongan, which is being built just over 60 miles from Beijing and is expected to be home to 2.5 million people. In June 2020, plans were unveiled for the car-free “Net City” in Shenzhen, which will be roughly the size of Monaco and is being built by tech conglomerate Tencent. Chris Van Duijn of the famous architecture and urban planning firm OMA told CNN: “Despite decades of urbanization in China, the repertoire of urban planning is still very limited. It seems we have only two conditions: it is either a city or it is a rural area. But as cities have expanded … people are also becoming interested in alternatives, ” he said. The OMA project in Chengdu described below “is not a typical urban project nor a landscape preservation project, but we hope to provide multiple ways in which city and countryside can both coexist and provide another type of urbanized development.” [Source: Jacqui Palumbo, CNN, February 9, 2021]

In the 2000s, the preferred term for a new urban project was Model City. Ambitions were less grandios. At that time, China planned to establish 432 new cities, most of which would ll have a population of more than 200,000. One of China's newest cities, Kunshan, resembled a miniature Singapore. It has housing projects with clean toilets, buildings painted in pastels, clean avenues lined with willow trees, tidy garbage-processing centers, a roller-skating rink, clean modern shopping centers, and a 28-story high-rise with a revolving restaurant.

Describing the model city of Zhangjiang (80 miles inland from Shanghai), Joseph Kahn of the Wall Street Journal wrote: "Sidewalks are hand paved with red clay tiles. Bicyclists don't swerve outside special lanes marked with red-and-white concrete barriers. Motorcyclists park outside the city; they are forbidden to drive within it for safety reasons. New high-rises, checkered with blue-tinted windows, are set well back from broad avenues. Heroic bronze statues of workers wielding shovels and athletes reaching for the sky abound. So do swathes of greenery. Fragrant camphor trees line the streets. The city's official flower, the red azalea, is stacked up by the thousands." The public rest rooms in Zhangjiang boasted one official, "smell so clean you could happily sleep in them." There were also are plans for large scale use of electric vehicles.

In the 2000s, architects, developers and builders sought LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) accreditation, a voluntary but highly sought after green building award developed and overseen by a US-based. non-governmental organization. Only a few Beijing constructions, including the 2008 Olympic Village, received LEED certification, although over 150 projects in China were registered to undergo the rigorous and lengthy inspection process. Under the LEED system, buildings applying for certification are comprehensively reviewed and awarded credits in five green design categories: sustainable sites, water efficiency, energy and atmosphere, materials and resources, and indoor environmental quality. Those that gain enough credits are awarded LEED certification — a status that invariably boosts real estate profitability as well as residents' long-term health and happiness. [Source: Daniel Allen, Asia Times August 18, 2009]

In 2020, AFP reported on an experimental green housing project in Chengdu in Sichuan Province that has been overrun by its own plants, with state media reporting that only a handful of buyers have moved in. [Source: AFP, Videographics, September 15, 2020].

Chengdu Future Science and Technology City

“A new “future city”, with an urban design intended to combine industry and technology with the bucolic countryside, is slated to open up outside of Chengdu in Sichuan province. Covering 4.6-square-kilometers (1.8-square-miles) and known as Chengdu Future Science and Technology City, it will contain several new universities, laboratories and offices. The architectural firms behind the project, unveiled in February 2021 with a series of digital images, are world famous Office for Metropolitan Architecture (OMA) and Gerkan, Marg & Partners (GMP). [Source: Jacqui Palumbo, CNN, February 9, 2021]

Jacqui Palumbo of CNN wrote: The development is being built in a rural area close to the forthcoming Tianfu International Airport, which is set to open later in 2021 and will make Chengdu only the third Chinese city, after Beijing and Shanghai, to be served by two international airports. “OMA, which designed Beijing’s eye-catching CCTV Headquarters in the 2000s, is responsible for a 460,000 square meter (nearly 5-million-square-foot) section of the new city, home to various educational facilities, known as the International Educational Park (IEP). GMP, meanwhile, will lead the design of a series of public spaces and transport facilities in an area dubbed the Transit Oriented Development (TOD).

“The two architecture firms were appointed based on separate entries to an international design competition. Digital renderings of the educational park show a sprawl of buildings with greenery on their roofs, curving in layers like the topography of terraced rice paddies. The buildings, which include university buildings, dorms, national laboratories and offices, mimic the hilly landscape to form a valley, with a 80,000-square-foot building nestled at its center.

“The campus was based on the natural surroundings rather than the needs of car traffic, said OMA partner Chris van Duijn, who leads the firm’s Asia projects. “Masterplans in China are typically based on infrastructure and quantities … the local topography (is) often ignored, ” said Van Duijn over email. “The result is that many masterplans throughout China look very much the same and opportunities to develop cities with local characteristics are missed.” GMP’s plans for its transit hub include overhauling an existing subway station and building a sculptural rotating viewing platform called the Eye of the Future.

Future Science and Technology City is not the only large-scale urban development being built in Chengdu. Also under construction in the Tianfu New Area, where the city’s new airport is located, is the so-called “Unicorn Island, ” a technology hub designed by Zaha Hadid Architects. Van Duijn said OMA anticipates that the first parts of its new project will be completed by the end of 2021, with the wider site finishing within another two years.

China’s Green Cities

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, “Rizhao, in Shandong Province, is one of the hundreds of Chinese cities gearing up to really grow. The road into town is eight lanes wide, even though at the moment there's not much traffic. But the port, where great loads of iron ore arrive, is bustling, and Beijing has designated the shipping terminal as the "Eastern bridgehead of the new Euro-Asia continental bridge." A big sign exhorts the residents to "build a civilized city and be a civilized citizen." [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

In other words, Rizhao is the kind of place that has scientists around the world deeply worried — China's rapid expansion and newfound wealth are pushing carbon emissions ever higher. It's the kind of growth that helped China surge past the United States in the past decade to become the world's largest source of global warming gases. And yet, after lunch at the Guangdian Hotel, the city's chief engineer, Yu Haibo, led me to the roof of the restaurant for another view. First we clambered over the hotel's solar-thermal system, an array of vacuum tubes that takes the sun's energy and turns it into all the hot water the kitchen and 102 rooms can possibly use. Then, from the edge of the roof, we took in a view of the spreading skyline. On top of every single building for blocks around a similar solar array sprouted. Solar is in at least 95 percent of all the buildings, Yu said proudly. "Some people say 99 percent, but I'm shy to say that."

Whatever the percentage, it's impressive — outside Honolulu, no city in the U.S. breaks single digits or even comes close. And Rizhao's solar water heaters are not an aberration. China now leads the planet in the installation of renewable energy technology — its turbines catch the most wind, and its factories produce the most solar cells.”

“In the end, anecdote can take you only so far. Even data are often suspect in China, where local officials have a strong incentive to send rosy pictures off to Beijing. But here's what we know: China is growing at a rate no big country has ever grown at before, and that growth is opening real opportunities for environmental progress. Because it's putting up so many new buildings and power plants, the country can incorporate the latest technology more easily than countries with more mature economies. It's not just solar panels and wind turbines. For instance, some 25 cities are now putting in or expanding subway lines, and high-speed rail tracks are spreading in every direction. All that growth takes lots of steel and cement and hence pours carbon into the air — but in time it should drive down emissions.”

Song era urban scene

Dongtan, the Failed Chinese Eco-City

In 2009, Dongtan’the planned eco-city on the salt flats of Chongming island in the Yangtze near Shanghai, which was supposed to be a model for the world by 2010 — was pronounced dead. Designed by British eco-engineers and green-minded architects from the London-based consulting group, Arup, the Manhattan-size city was set up to run on renewable energy, be car-free, and recycle all of its water and have and have 25,000 people living in it when the Shanghai World Expo opened in 2010 and when it could be reached by a new tunnel and bridge.[Source: Fred Pearce, The Guardian, April 23, 2009]

British Prime Minister Tony Blair signed the deal to design and build Dongtan with Chinese president Hu Jin-tao. His deputy, John Prescott, went there twice. So did Britain's top urban planner, Peter Hall, and the London mayor Ken Livingstone, who wanted ideas for greening his urban landscape. Ma Cheng Liang, the man in charge of the project, said in early 2006: “We need to reduce our ecological footprint. Dongtan is very significant for Shanghai and the nation. We want to skip traditional industrialization in favor of ecological modernism. Dongtan is a chance to develop new ways of living.”

When Expo 2010 and the tunnel and bridge opened nothing was in the eco-city except half a dozen wind turbines and an organic farm. There were no houses, no water taxis, no sewage-recycling plant, no energy park. Mentioned of vanished from the Expo website.

Peter Head, the main Arup designer of Dongtan, denied rumor that the project has been a casualty of the political fallout from the conviction of the city boss Chen Liangyu, jailed in 2008 for corruption. Rather said it was the result of the way China operated. “China does everything by the rules handed down from the top. There is a rule for everything. The width of roads, everything. That is how they have developed so fast, by being totally prescriptive. We wanted to change the rules in Dongtan, to do everything different. But when it comes to it, China cannot deliver that.” he said [Source: Fred Pearce, The Guardian, April 23, 2009]

Paul French, chief China analyst at Access Asia, said Dongtan had died because planners had failed to consult the local community and had aimed too high. “Dongtan was plonked down on everyone. They were going to do everything, but nothing has been realized. It's really important with environmental stuff that you only say what you can actually deliver or people will lose trust.” [Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, June 4, 2009]

New Tianjin Eco City in China

China and Singaporean have mapped out a huge eco city for 350,000 people in Tianjin that they hope will be model could be copied across developing countries. The buildings will be the latest word in energy efficiency: 60 percent of all waste will be recycled, and the settlement will be laid out in such a way as to encourage walking and discourage driving.[Source: Jonathan Watts, The Guardian, June 4, 2009]

The plan to build this settlement, known as Tianjin Eco-City, near the western shore of the Bohai, one of the most polluted seas in the world. Groundbreaking for the the first phase. Tianjin — an “eco-business park” over 150 hectares (370 acres) — took place in 2009.

Every building is to be insulated, double glazed and made entirely of materials that abide by the government's green standards. To cut car journeys by 90 percent, a light railway will pass close by every home, and zoning will ensure all residents have shops, schools and clinics within walking distance. It will be more verdant than almost any other city in China, with an average of 12 square meters (nearly 130 square feet) of parks or lawns or wetlands for each person. Domestic water use should be kept below 120 liters (26 gallons) per person each day, with more than half supplied by rain capture and recycled grey water.

One of the first aims of Tianjin Eco-City is show it can avoid the failures that doomed another eco-city, Dongtan (See Below). Goh Chye Boon, chief of the joint venture running the business park at Tianjin Eco-City, said his project had learned from Dongtan that it was better not to reach immediately for the skies. “We aspire to one day be a dream city like Dongtan but we want to take one credible step at a time,” he tolf The Guardian. “Dongtan inspired me, but I think when you reach too high, you may forget that the ultimate beneficiary must be the resident.”

According to The Guardian the “new city being built in Tianjin is in danger of going too far the other way by not being ambitious enough. Although it will use wind and geothermal power, its target of 20 percent of energy from renewable sources by 2020 is only a tiny improvement on the goal for the national average. The goal for carbon emissions is equally modest.”

Ghost Cities of China

China is home to cities with brand new skyscrapers and shopping malls, but mostly silent streets and empty apartments. It is said there millions of empty apartments in these cities as well as cinemas and parks that no one uses. The term ‘ghost cities’ is used to describe places such as Ordos, described below, in Inner Mongolia. [Source: Manya Koetse, What's on Weibo, November 13, 2015; Dan Levin, New York Times ]

Wade Shepard, author of “Ghost Cities of China” (2015), told the New York Times: “The term ‘ghost cities’ is actually not appropriate. Ghost cities are places that once lived and then died. What I write about is new places that are underpopulated, and where houses are dark at night.” Most of China’s ‘ghost cities’ have people living in them or are still under construction: “These new underpopulated cities are built by world luxury developers who are working on constructing new urban utopias all over China. The people living in these cities come from various places. Some are trendy people who are looking to live in a new city. Others have been relocated from their original villages. There are many from the countryside.”

“I saw a ‘ghost city’ for the first time in 2006, when I was a student near Hangzhou, ” Shepard said.“It happened in the small town of Tiantai. I took a wrong turn after getting off the bus, and I ended up in this new part of town with nobody there. Never in my life had I seen anything like it: a brand new neighbourhood with nobody there. I was so excited about it. My professors later told me those places were everywhere, they were not impressed. But it stuck with me. Just take any bus, and there is going to be a new city or neighbourhood under construction. I enjoyed walking around these areas.

“There is an upside and a downside to the emergence of China’s new cities, Shepard explains: “There are people who are very happy to move there. Because they get a urban hukou” — the valuable urban residency permit that allows to legally work in a city and entitles them to city services such as schools and health care — “they feel like they’re moving up. But there is also a big downside to China’s urban migration. Many people are moving from a traditional village structure, where people make daily social connections, and ask each other what they are doing today and what’s for dinner tonight. With these high apartment buildings, this structure changes; they don’t do that anymore. It’s an elevator culture. People also come from so many different places that they don’t really connect.”

Book: “Ghost Cities of China” by Wade Shepard (2015). Film: “The Land of Many Palaces” by Adam J. Smith and Song (2015).

Ordos, China’s Most Famous Ghost City

Ordos Kangbashi (700 kilometers west of Beijing) is a beautiful modern city that was built from the ground up in just five years. It is now now more filled up than it was but for some time it was described as a modern ghost town, with clean streets and charming, quite, neighborhoods but few people. The city was built to accommodate nearly one million people, for a while there only a few hundred thousand. As of teh late 2010s, there were are about a half million people there.

Ordos Kangbashi was built on a patch of desert between 2005 and 2010. It has skyscrapers, stadiums, an impressive theater, a museum and highrises with thousands of apartments. Many of the people that moved there came straight from countryside. Some had never used modern toilets, stoves or heaters and had to shown how a modern television works Employment was an issue. Many farmers have ample experience in raising pigs and working on the land, but their experience is of no use in the urban environment where there is more need for hair stylists and shop attendants. The lack of jobs is one important reason why farmers don’t want to migrate from the countryside to the city. In 2012, Ordos Kangbashi was the venue for the Miss World Final. By 2017, Kangbashi had become more populated with a resident population of 153,000 and around one-third of apartments occupied. Wade Shepard wrote in Forbes: "Of the 40,000 apartments that had been built in the new district since 2004, only 500 are still on the market. [Source: Manya Koetse, What's on Weibo, November 13, 2015]

Ordos lies in the deserts of southern Inner Mongolia near coal-mining area of Shaanxi province. It is home to the world's biggest coal company and the planet's most efficient mine. The area around Ordos holds an estimated one-sixth of China's coal reserves. The extensive coal and gas deposits below Ordos has turned this arid, northern outpost into a boom town. After coal began seriously being developed, the region went from being one of the poorest parts of China to one of richest. The local economy grew eightfold between 2004 and 2009 while the population has swollen almost 20 per cent.People became millionaires investing real estate and building housing and in infrastructure.

Ordos offers some insight into what happens when planned cities don't work out as planned. Ordos had grown rich suppling coal and minerals to the rest of China. As of late 2010 the average per capita income was around US$21,000, the highest in the nation and nearly triple the national average. When people talk about Ordos they are often referring to Kangbashi. Between the 2004 and 2010 it was transformed from two villages in the grassland to cluster of grandiose buildings, including an opera house shaped like two traditional Mongolian hats, a library that resembles three massive books and museum that looks like a giant copper boulder. Many of the units in the apartments blocks were bought up by investors. The city has a capacity of 300,000 people. As of 2010 it had about 30,000.

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic, “Ordos may be the fastest growing city in China; even by Chinese standards it has an endless number of construction cranes building an endless number of apartment blocks. The city's great central plaza looks as large as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, and towering statues of local-boy-made-good Genghis Khan rise from the concrete plain, dwarfing the few scattered tourists who have made the trek here. There's a huge new theater, a modernist museum, and a remarkable library built to look like leaning books. Coal built this Dubai-on-the-steppe. The area boasts one-sixth of the nation's total reserves, and as a result, the city's per capita income had risen to US$20,000 by 2009. (The local government has set a goal of US$25,000 by 2012.) It's the kind of place that needs some environmentalists. [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

Ordos was a government project, likely conceived at least part as an economic stimulus. Building is a sign of economic growth. So, local officials started building. Ordos also offers some insight into what happens when planned cities don’t work out as planned. Ordos had grown rich supplying coal and minerals to the rest of China. As of late 2010 the average per capita income was around $21,000, the highest in the nation and nearly triple the national average. Between the 2004 and 2010 Kangbashi Ordos was transformed from two villages in the grassland to cluster of grandiose buildings, including an opera house shaped like two traditional Mongolian hats, a library that resembles three massive books and museum that looks like a giant copper boulder. Many of the units in the apartments blocks were bought up by investors. The only thing that was missing was people. The city has a capacity of 300,000 people but only had about 30,000 in 2010.

Bill McKibben wrote in National Geographic in 2011, “Ordos may be the fastest growing city in China; even by Chinese standards it has an endless number of construction cranes building an endless number of apartment blocks. The city's great central plaza looks as large as Tiananmen Square in Beijing, and towering statues of local-boy-made-good Genghis Khan rise from the concrete plain, dwarfing the few scattered tourists who have made the trek here. There's a huge new theater, a modernist museum, and a remarkable library built to look like leaning books. Coal built this Dubai-on-the-steppe. As a result, the city's per capita income had risen to $20,000 by 2009. (The local government has set a goal of $25,000 by 2012.) It's the kind of place that needs some environmentalists. [Source: Bill McKibben, National Geographic, June 2011]

Ordos — 90 Percent Full in 2016?

In 2016, the Chinese government said that Ordos was roughly 90 percent occupied. But was that really the case in its famous ghost city. Reporting from there at that time, Wade Shepard wrote in Forbes: “Ordos is a prefecture level city of two million people. In China, prefecture level cities are usually broken up into smaller districts, counties, sub-cities, towns, and villages. Within the expanse of Ordos, Kangbashi sits on the border of Dongsheng district and Yijinhuoluo, which is part of a county-level division called Ejin Horo Banner. The new city, which began being constructed in 2004, now stretches unimpeded across the Wulanmulun River, which is the frontier between these two administrative areas. Kangbashi’s core downtown is on the north side of the river, while masses of housing complexes are on the south side. When looked at from the ground it all appears to be one contiguous urban area, and nobody would second guess that it was same place. [Source: Wade Shepard, Forbes, April 23, 2016]

“What makes Ordos Kangbashi even more mysterious than being a completely new city built out in the middle of the desert is the fact that the place is yet to be recognized as an administrative entity in its own right. Although this new city currently has a population approaching 100,000 people, in the view of Beijing it doesn’t exist. However, Kangbashi’s administration is attempting to change this by petitioning the capital for county-level city status, which, when granted, will formally put the place on the map.

“The interesting thing is that Kangbashi’s application for official recognition conspicuously leaves out the area to the south of the Wulanmulun River. This, perhaps not coincidentally, happens to be where the majority of its empty housing is located. Essentially, by snipping off this area from Kangbashi proper, the place suddenly becomes almost completely inhabited, having just four or five under-occupied housing complexes. So much for that ghost city critique.

“While dividing Kangbashi up between two different administrative entities may seem like an easy way for the new area to dispel the ghost city critique and make it appear more successful than it may actually be — which may have been intentional — this isn’t completely the case. In order for a new city in China to be officially recognized, a certain set of qualifications need to be met. Namely, population, GDP, size, and facilities must be at a specified level. In order for Kangbashi’s bid for county-level city status to be successful, it would have to trim off some fat. In this case, this meant cutting off the under-inhabited area on the other side of the river.

“However, it could be argued that this area in question was never really a part of Kangbashi in the first place. As the new city was never an official urban entity, where it actually begins and ends can be debated. When the area to the south of the river was initially being built in 2010 it was designed to become the southern area of Kangbashi, but, as is the case with nearly all of China’s large-scale urbanization endeavors, a lot can change between the time a new project is conceived and when it is actually finished.

“This is intensified due to the organization structure of the Communist Party, which sees high-ranking officials cycled out of office roughly every five years. So what one official does with a certain project may be very different than what his predecessor initially intended. In China, it’s a given that when leaders change, plans change. Although however the place is divided up, the view of this part of Ordos looks the same from the ground: a budding new urban area that’s trying hard to diversify its economy, create new opportunities, and bring in new businesses and more residents. But this may mean that those of us in media need to update our narrative: Kangbashi is no longer the ghost city, Yijinhuoluo is.

Tieling, China’s Highly-Praised, Green Ghost City

Reporting from Tieling, Dinny McMahon of the Wall Street Journal wrote: “When this small city in northeastern China launched a plan to build a satellite city six miles down the road, it got off to a promising start. Urban planners spent millions of yuan to clean up surrounding marshland that had become a dumping ground for the city's untreated sewage. A pristine environment, they hoped, would help attract the businesses that would raise incomes and swell the population. Four years later, Tieling New City is virtually a ghost town. Clean waterways weave among deserted residential and government buildings. Housing blocks that won recognition from the United Nations for providing good affordable homes are almost empty. The businesses that were supposed to create local employment haven't materialized. Without jobs, there is little incentive for anybody to move here.” [Source: Dinny McMahon, Wall Street Journal, August 9, 2013 ~]

For an urban center like Tieling to prosper “it must create jobs that will draw people into the cities. Tieling underscores the difficulty. Among the few business owners lured to a development park in Tieling New City is Bo Yuquan, the middle-aged owner of a flooring store. "Where are the people? There's no one here," said Mr. Bo. "I'll be out of business soon. My staff and I are discussing moving to Beijing to find work." Said Hu Jie, the designer of the new city's landscape: "In 10 to 20 years, Tieling could be a good development, but only if you can manage to bring businesses in." ~

“Tieling, a city of about 340,000, launched its plan to build a new city in 2005, part of a broader strategy by the Liaoning provincial leadership to revive a local rust-belt economy. The plan was to stimulate growth around Tieling and six other nearby cities by building highways and high-speed rail lines connecting them with Shenyang, a metropolis that is about a 90-minute drive south of Tieling. The idea was that companies would be drawn to the satellite cities by cheaper land and lower labor costs, while still enjoying proximity to the region's largest city. Tieling's new city was expected to house 60,000 residents in 2010 and later triple that number. ~

In 2009 the wetlands' rejuvenation was complete, along with the new city's infrastructure, canals, government offices and some apartment buildings. The new city won a special mention from the U.N. Human Settlements Program for "providing a well-developed and modern living space." But come dusk, the lights in row after row of apartment buildings remain off. Salespeople, security guards and the small smattering of residents say almost all of the accommodation is empty. A development park set up to attract providers of back-office services to financial firms, such as data storage, was supposed to employ 15,000 to 20,000 people by the end of the this year, according to the park's website. ~

“Situated on the outskirts of the new city, the park is easy to miss. It is home to only two companies, one of which, a bank office, employs fewer than 20, said its security guard. Another park filled with warehouses outside the new city fares little better. Marketed as a trading hub for China's northeast region, it was supposed to foster a logistics industry by taking advantage of Tieling's location near two major highways and a port, with rail links to Shenyang and the rest of the northeast.Although most of the shop space has been sold, the park lies largely empty except for a handful of wholesalers. Meanwhile, there are plans for the park to double in size, an expansion that would include more apartment buildings. "The park doesn't have any advantages over Shenyang's wholesale markets," said Liu Wei, a researcher at the government-backed Institute of Comprehensive Transportation, who worked on Tieling's plans for a logistics center. ~

“So far, the new city's greatest success has been a zone dedicated to building special-purpose vehicles such as snowplows. According to a statement on the Tieling government website in April 2012, the park created 5,000 jobs for rural workers. But it also said the workers had bought apartments in a residential compound across the road from the park, far from the city centers of both old and new Tieling. The few rural migrants who live in the new city used to farm the land it was built on. Some now work for the new city shoveling snow and sweeping streets. ~

“Local authorities have tried to boost the population by pushing people from the old city into the new. That effort has involved moving government offices into the new city. But so far, most government workers still commute from their existing homes. The effort also has involved closing schools in the old city and the greater Tieling county and corralling the students into newly built schools in the new city. According to Sun Baocai, the office director of the Tieling Bureau of Education, 50,000 students are enrolled in classes in the new city, ranging from elementary classes to vocational courses. The hope is that parents will move to be closer to the schools. But many residents of the old city say that despite the new city's pleasant environment, its lack of services and absence of a community deter them from moving. ~

Against all this, Tieling is choosing to keep building. The municipal government has rolled out plans to spend a further $1.3 billion on projects in the new city this year, including an art gallery, gymnasium and indoor swimming pool. That is despite municipal finances coming under increasing stress."Financing costs are rising all the time, and raising capital has become even more difficult," the Tieling city government said in its budget forecast for 2013. "Some long-term problems and imbalances have accumulated in the management of the city's finances." It didn't say how it planned to fund the new buildings. Cui Xinzi runs a stall selling leather jackets at the only shopping center in the new city. Despite having bought an apartment there three years ago, she still lives in the old city and commutes. Ms. Cui likes the idea of retiring to the new city but isn't optimistic its population will increase. "It still needs more time, but it's really hard to say," she said with a sigh. "They're building a new shopping center, so I hope so." ~

Image Sources:

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated October 2021