HUKOUS, CHINA’S ALL-IMPORTANT RESIDENCY CARDS

a hukou

All Chinese citizens need a carry “hukou” (residency card) to live in a city named on the card or move from one place to another. A kind of internal passport, the hukou system was implemented in 1958 to halt migration, control grain rations, and keep tabs on the masses and give rural people a connection to their land. Modern ones are imbedded with chips that have person’s name and place of birth .

A residency card is one of the most valuable documents in China. It is necessary to get an apartment and job in a town or city and send children to school. There are many stories of husbands and wives that are separated because the husband got a good job in a distance town and his wife couldn't secure a new hukou. Peasants migrate to cities without hukous in search of jobs and have trouble getting decent housing and places for their kids in school.

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “One of China's oldest tools of population control, the hukou is essentially a household registration permit, akin to an internal passport. It contains all of a household's identifying information, such as parents' names, births, deaths, marriages, divorces, moves and colleges attended. Most important, it identifies the city, town or village to which a person belongs.” [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

Bloomberg reported: “Large cities such as Shanghai, Beijing and Chongqing have a strict quota each year on the number of people who are allowed to become local residents. Almost 10 million people live in Shanghai without a local hukou — more than 40 percent of the city’s population — Huang Hong, chairman of the Shanghai Municipal Population and Family Planning Commission, said in a Dec. 11 post on the local government website. [Source: Bloomberg News, December 17, 2012 |+|]

See Separate Article EVERYDAY LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; RURAL LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; URBAN LIFE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; MIGRANT WORKERS AND CHINA’S FLOATING POPULATION factsanddetails.com ; LIFE OF CHINESE MIGRANT WORKERS: HOUSING, HEALTH CARE AND SCHOOLS factsanddetails.com ; HARD TIMES, CONTROL, POLITICS AND MIGRANT WORKERS IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; LOCAL GOVERNMENT IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China ; BUREAUCRACY, WELFARE AND TAXES IN CHINA Factsanddetails.com/China

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Urbanization with Chinese Characteristics: The Hukou System and Migration” by Kam Wing Chan Amazon.com; “Contesting Crimmigration in Post-hukou China” by Tian Ma Amazon.com; “A Deep Analysis of the Chinese Hukou System: Facts, Impacts, and Reform Paths” by Yang Song Amazon.com

History of the Hukou System

Inspired by family registers from centuries ago, the hukou (pronounced WHO-ko) system was introduced in 1958 under Mao Tse-tung as a means of social control and was designed to bind farmers to their land. The household registration permit limits where Chinese citizens can live, work and go to school by splitting them into two categories — urban and rural.

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “ “The hukou dates back at least 2,000 years, when the Han dynasty used it as a way to collect taxes and determine who served in the army. Mao Zedong's Communist regime revived it in 1958 to keep poor rural farmers from flooding into the cities. It remains a key tool for keeping track of people and monitoring those the government considers “troublemakers.” [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

Fang Lizhi wrote in the New York Review of Books, “This registry system... was not a Chinese invention. It was brought to China during World War II by the invading Japanese, who wanted to halt migration in order to prevent the spread of popular resistance. (The Chinese word for “registry police” comes from Japanese.) Yet Deng Xiaoping, the alleged “education reformer,” enforced this household registry system, and its consequences for education, to his dying day. His successors, too, have enforced it. Vogel refers to the system once, explaining that farmers who moved to cities “were trying to live surreptitiously there with relatives or friends” and caused leaders to fear “that a torrent of rural migrants could overwhelm — urban services such as housing, employment, and schooling for children.” [Source: Fang Lizhi, New York Review of Books, November 10, 2011]

The government is afraid is to get rid of internal passports out of fear they such a move would encourage more rural people to migrate to the cities which are already overextended and busting at the seams. The inability of the government to keep track of all the migrants has made it easier for criminals and dissidents to hide from authorities, and, the government worries, for migrants to organize political protest without the police knowing about it.

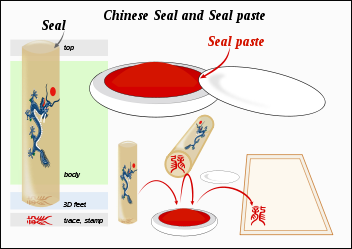

Chops

Instead of signing their name, Chinese stamp their name on forms, bank withdrawal slips and letters with a chop, or signature stamp). Without a chop one can't open a bank account in China or register for a university class. One professor told the Los Angeles Times, "I don't exist in this society without my chop." [Source: Mark Magnier, Los Angeles Times, November 28, 2001]

Chops are cylinders about the size of a piece of chalk. They have the person’s name carved at one end in Chinese characters and they leave an imprint after being stamped in ink Everyone from the President to a homeless man living in a park has a chop, and they are used for everything from finalizing a multi-million-dollar business deal to signing for packages delivered to one’s house. At some businesses if you forget your chop, no problem, they’ll let you use someone else’s.

The average Chinese has five chops but only one is registered with the government to certify ownership and it is only used on important documents. Since these seals are considered too valuable to carry around, people have other seals to use for things like bank transactions and taking deliveries. Many government documents have several chop stamps. According one estimate a typical bureaucrats puts his chop on 100,000 documents in a 25 year career.

Thousand of years ago Chinese used the imprints of fingers as a way of signing contracts. Chops have a 5,000 year history. Signature seals, which operates according the same concept, were used in ancient Mesopotamia and China. Japan's oldest example of writing is a solid-gold chop dated to A.D. 57.

Privileges and Opportunities Denied by the Hukou System

David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Those lucky enough to hold an urban hukou, particularly in vibrant cities such as Beijing and Shanghai, have access to urban schools, hospitals and jobs that are far superior to those in the countryside. Rural hukou holders are welcomed in urban areas only when they are needed as construction workers, waiters, cooks, factory hands and nannies. But authorities don't want them planting roots and overwhelming China's cities. They are in effect barred from bringing their children and extended families because they face prohibitive fees for obtaining education and other public services in the cities.” [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, December 12, 2012]

According to the China Economic Review: “Urban hukou status opens the door to a suite of resources for migrants. Without it, they struggle to gain access to basic health care and schooling for their children. Crucially, they're also excluded from China's affordable housing program, a central government scheme that subsidizes the rent on modern housing for poor urban hukou holders. [Source: China Economic Review, May 19, 2014]

Bloomberg reported: “Attaining a local hukou may depend on a person getting sponsored by a state-owned company or reaching a certain level of education. Without the pass, people can be denied everything from discounted city park tickets to subsidized health care. The hukou may also be used to coerce people into doing what the government wants. In Henan province, officials seeking to enforce China’s one-child policy forced women to get contraceptive implants before they were allowed hukous for their newborns, China Central Television reported. Many rural families are larger, due to exceptions to the rule or because parents choose to pay a fine for having more children. [Source: Bloomberg News, December 17, 2012 |+|]

Hardships and Discrimination Under the Hukou System

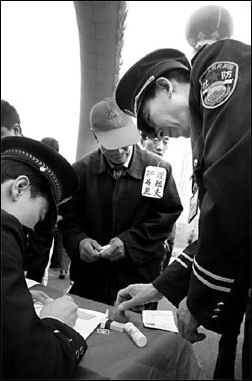

checking for a hukou

Under the hukou system migrant workers, who in many ways fuel the booming Chinese economy, cannot get urban ID cards. “Critics say the hukou system perpetuates China's growing urban-rural divide,” Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post. “Migrant workers flock to the coastal cities to labor in factories and take other manual jobs, sometimes living many years in places such as Beijing, Shanghai and Guangzhou. Because they lack an "urban hukou," they are forever designated "temporary residents" — unentitled to subsidized public housing, public education beyond elementary school, public medical insurance and government welfare payments.” [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

“People who live in a city such as Beijing but do not have a local hukou must travel to their home towns to get a marriage license, apply for a passport or take the national university entrance exam. Parents and students say the last requirement is particularly onerous, especially if a student has to take the exam in a province that uses different textbooks.”

According to an editorial in the China Daily, a mouthpiece of the Chinese government: “The policy barriers preventing them from sending their children to the same schools as the children of their urban counterparts, from applying for low-rent and other types of social welfare homes, and from enjoying the other social benefits enjoyed by urban hukou holders, are not only unfair, they are against the principle of an inclusive society and should be removed as early as possible. Improving the quality of life for these migrant workers, by granting them the same status as urban residents, will increase their capability and willingness to consume - something China needs if it is to sustain its economic growth in the future. The central government is well aware that this is one of the major defects of China's urbanization and that it must be addressed. In Premier Wen Jiabao's government work report early this month, gradually integrating farmers-turned-workers into urban societies was listed as one of the key tasks for the government. Beijing's move is an initial step toward accomplishing that task and sets a good example for the rest of the country. But if anything, instead of piecemeal moves, a clear policy roadmap is needed to better facilitate this task.[Source: China Daily, March 22, 2012]

People Discriminated Against Under the Hukou System

hukous Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “Wang Aijun is the editor of the Beijing News, one of China's most influential private daily newspapers. Yet here in the capital, Wang said, he often feels like a second-class citizen. He pays Beijing taxes, but his teenage son is not allowed to attend a Beijing public high school. To install a telephone or an Internet line, he must pay in advance. He is charged more for a ticket to some city parks. He doesn't qualify for a subsidized apartment. He cannot enroll his family in the city's public health-insurance program. The reason for the discrimination? Despite having lived and worked in Beijing for seven years, Wang still does not have that most sought-after of commodities: a Beijing "hukou." [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

Wang, 42, moved to Beijing seven years ago from Zhengzhou, in Henan province, after he became editor of the Beijing News. The paper could not get him a Beijing hukou, but he took the job anyway. "I thought I should do something I was interested in," Wang said. "I also thought China's hukou system would be reformed in six or seven years."

Wamg estimates that nearly a third of Beijing's 22 million-plus people do not have a Beijing hukou “including, he said, most members of his newspaper staff. Some reports put the number of temporary residents in the capital at 8 million. "I've gotten used to living in Beijing without a hukou," Wang said. "A hukou is like the air — you don't think about it normally. But once you need it and don't have it, you get pretty upset." Wang cited the fees he must pay for his 15-year-old son's expensive international school.

Social Divisions and the Hukou System

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post: "Some economists here say the hukou system is outdated and unsuited to a modern economy that requires the free movement of labor. Others call it "China's apartheid," saying it has created a two-tiered system of haves and have-nots in all the major cities. "You have a large number of rural migrants who already earn most of their income in the cities, who have been in the cities a long time, but do not have hukou-related benefits," Tao Ran, an economist at Renmin University told the Washington Post. "This system is very bad; it's ridiculous." [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

David Pierson wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “For millions of Chinese, the difference between a life of struggle and one of opportunity comes down to...the hukou. The hukou, has created a modern economic chasm between city dwellers and peasants that threatens China's economic future as a powerhouse world economy. The hukou system also has become a flash point in China's wealth gap. Pent-up frustration with the country's growing divide has erupted in violent protests and riots. [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, December 12, 2012 ]

Anger over the household registration system exploded in November 2012 on China's frenetic micro-blogs after five rural boys in southern Guizhou province died of asphyxiation; the children had been huddled in a dumpster where they had lit a fire to escape the cold. The youngsters were part of the so-called left-behind generation, unable to join their parents in the city because their families couldn't afford the extra school fees charged to migrants. The issue has become so sensitive that the journalist who broke the story has reportedly been detained by authorities. "The popular narrative about migrants' lives getting better by the second generation doesn't work in China because children there also suffer from a lack of access to equal rights and equal opportunity," said University of Washington professor Kam Wing Chan, an expert on Chinese migration and hukou policy.

People Desperate to Get a Beijing Hukou

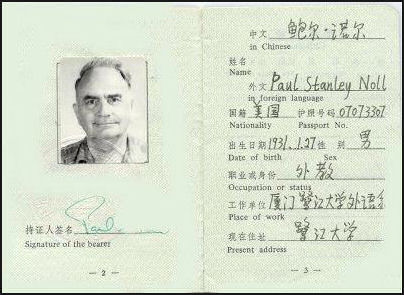

Residency document for a foreign teacher

in China in the 1990s

The Beijing hukou is the most prized, if only because it is the hardest to get,” Richburg wrote. “One reason is education: The capital has the country's most highly regarded universities, and those schools reserve a large quota of places for Beijing hukou-holders. Chinese from outside the city can switch to a Beijing hukou by joining the civil service, getting a job with a state-owned company or achieving a high military rank. [Source: Keith B. Richburg, Washington Post, August 15, 2010]

Some get desperate, taking a job they don't really want if it offers them a hukou. Peng Li, 29, graduated with a law degree from a Beijing university in 2008 and was offered work in a company's legal office. But the offer did not include a guaranteed Beijing hukou, so she took a job as an official in a Beijing suburb. "This job is kind of boring, and the salary is not high," she said. "I regarded it as a springboard to getting a Beijing hukou."

Some young people seeking a spouse on popular Internet sites will state upfront that they prefer a partner who has a Beijing hukou. "Girl, 26, from North China, 161 cm tall . . . looking for a guy who was born between 1976 and 1983 and wants to marry within three years," says one posting on a popular site by a girl calling herself "imzly." "I hope you . . . have a Beijing hukou (because I don't have one)."

Reforming the Hukou System?

a chop is used instead

of signature In China China's leadership appear to recognize the need to overhaul the hukou system. The issue received some attention at the Communist Party congress in November 2012. Outgoing President Hu Jintao said China must “keep making progress in ensuring that all the people enjoy their rights to education, employment, medical and old-age care and housing.” Incoming President Xi Jinping said: "Our people have an ardent love for life. "They wish to have better education, more stable jobs, more income, greater social security, better medical and healthcare, improved housing conditions and a better environment." [Source: David Pierson, Los Angeles Times, December 12, 2012]

Reform has been slow in coming largely because of resistance from municipalities. Most local tax revenue is controlled by the central government, leaving cities few resources to expand public services for migrants. Tom Miller argues in his book “China’s Urban Billion” the long overdue reform of the hukou system has been dodged by successive administrations in large part because of the astronomical financial strain it would place on city budgets. Lifelong social security for each new urbanite would cost about £10,000. If urban benefits and welfare were extended to 300 million migrant workers over the next couple of decades, the bill would be around £150 billion. [Source: Leo Lewis, The Times, January 22, 2013]

Andrew Jacobs wrote in the New York Times Policy makers have been discussing hukou reform for two decades, but beyond limited experiments in Shanghai, Chongqing, Chengdu and a smattering of second-tier cities, the National People’s Congress, China’s lawmaking body, has declined to act. Resistance comes from factory owners who want migrant laborers to remain insecure and cheap to exploit, and from urban elites who fear an even greater deluge of migrants from the countryside if it becomes easier to live in the city. But the most formidable opposition may be that of local governments, which worry about paying for the health care, education and other benefits that migrants and their children would qualify for as legal residents. [Source: Andrew Jacobs, New York Times August 29, 2011]

In 2010, 15 Chinese newspapers ran a joint editorial calling on Beijing to immediately scrap the "inhumane" hukou system. Some have speculated that China’s labor shortage might embolden migrant to demand a speedier end to the hukou system, which violates the Chinese Constitution.In 2007, the Chinese government began issuing residency cards to the 150 million people that had moved to the cities but had not yet acquired residency. The aim was aimed at addressing crime and gaining better control over China’s floating population of migrants.

In the 12th Five-Year Plan in 2011, reform of the hukou reform was is mentioned as a possible tool to promote labour mobility, boost incomes, rebalance the growth model towards consumption and create a stable urban society. While there has been a lot of "talk of reforms", concrete proposals remain scarce so far (beyond some experiments at the provincial level). In the context of growing urbanisation pressures in China, a hukou reform is increasingly becoming both an economic and political necessity. In view of its complexity and heavy financial implications, the hukou reform appears as a litmus test of the new leaders' willingness and capacity to undertake reform. [Source: Bu Annika Melander and Kristyna Pelikanova, ECFIN Economic Briefs no. 26, July 2013]

Relaxing the Hukou System

Keith B. Richburg wrote in the Washington Post, “In the 1990s, some cities, including Shanghai, Shenzhen and Guangzhou, began allowing people to acquire a local hukou if they bought property in the city or invested a large sum of money. Shanghai further relaxed the rules last year so that professionals who have lived in the city for seven years as tax-paying temporary residents could qualify....The Beijing government has taken several small steps toward hukou reform over the years. A Beijing pension can now be transferred to another city, for example, and the city's public kindergartens and grade schools were recently opened to all students, regardless of hukou status.”

Tania Branigan wrote in The Guardian, “Cities such as Chongqing and Guangdong have been experimenting with limited hukou reform. But such programmes are often tightly restricted and cover workers who have moved from country to town within a province. In many cases migrants have been wary of switching registration, fearing the compensation for lost land and home is insufficient to establish them in the city. [Source: Tania Branigan, The Guardian, October 2, 2011]

Kam Wing Chan, an expert on migrants at the University of Washington, told The Guardian reforms needed to go deeper and to involve Beijing."Hukou reform has to be gradual, but it has to tackle the core of the issue," he says. "The core issue, for example, in Guangdong, is to gradually accept migrant workers from outside the province — the majority of the migrant workers — as equals."

Abolishing the Hukou System?

Some critics advocating an overhaul of the hukou system “or abolishing it altogether — said changes must be gradual to avoid large-scale disruption. Some have recommended assigning hukous by income or giving priority to those who have paid taxes in a city. Whatever the pace of change, experts said, the hukou has outlived its usefulness. "Migration is inevitable," said Tao of Renmin University. "We're proposing the government should just open all the cities."

Branigan wrote: Wholesale hukou reform is an alarming prospect for officials, raising the spectre of an expensive and uncontrollable surge to the cities. But the alternative is an unbridgeable gap between town and country. Willy Lam wrote: Many government officials worry that throwing out the hukou regime could lead to more overcrowding in already very populous cities ranging from Beijing and Tianjin to Shanghai and Shenzhen. Pleading that their health, education and social-welfare facilities are stretched to the limit, cadres have vigorously opposed allowing more migrant workers to settle in the east. [Source: Willy Lam, China Brief, March 10, 2011]

Ending the Hukuo: an Engine for Growth?

Yukon Huang, a former country director for China at the World Bank and now a senior associate at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace’s Asia Program in Washington, told Bloomberg that ending the hukou system “would probably increase growth by half a percentage point a year.” [Source: Bloomberg News, December 17, 2012 |+|]

According to Bloomberg: Overhauling the system would help expand a consumer class as migrants to cities settle there, buying homes and household goods rather than sending money home, said Kam Wing Chan, a professor at the University of Washington in Seattle who has consulted for the World Bank on the hukou system. That would help shift China’s economy from one driven by exports to one based more on consumer demand, he said. “A lot of them are saving up to build a house back in the countryside,” Chan said. “They are coming to work, they are not really spending, and the system prevents them from moving up because a lot of opportunities are not opening to them.” |+|

“Inequality between China’s rural residents and its city- dwellers has led to a wealth gap that’s now 50 percent higher than the minimum level that can trigger social unrest, according to a survey by the Survey and Research Center for China Household Finance. Xi Jinping pledged to tackle the gap after he was named Communist Party general secretary. Overhauling the hukou system would require changes to local government finances, said the University of Washington’s Chan. The central government distributes money to local authorities based on the number of registered residents they have.

Phasing Out the Hukou System?

The China Economic Review reported: “In March 2014, the central government set a rough timeframe for phasing out the hukou system, under which rural migrants are barred from accessing welfare benefits in the cities in which they work. By 2020, the plan says 100 million workers and other permanent residents will receive urban hukous. [Source: China Economic Review, May 19, 2014 \^/]

“By Kam Wing Chan's count, many migrants will never integrate fully into China's cities. The plan the government put forward this year is “largely the same as the old one,” Chan said. Leaders in Beijing have simply drawn from and synthesized older urbanization plans to form the new one. At the pace marked out by the government, Chan says comprehensive reform to the hukou system could take up to 50 years. Many migrants might as well consider their outsider status permanent. \^/

Image Sources: Nolls site, Beifan.com, CG Stock, Picasaweb; Wiki Commons, Wikipedia, Asia Obscura

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated July 2015