SPECIES OF RHINOCEROS IN ASIA

Indian rhinoceros

Of the five species of rhinoceros, three are in Asia: 1) the one-horned Indian rhinoceros in India and Nepal, 2) the one-horned Javan rhinoceroses in Java and previously Southeast Asia, 3) the two-horned Sumatran rhinoceros in Sumatra and previously Borneo. All species of rhinos are extremely endangered due to overhunting and destruction of their habitat. Humans have hunted rhinos extensively because nearly all parts of the animal have been used in folk medicine. The most prized part of the rhino is its horn, which has been used as an aphrodisiac, fever-reducing drug, dagger handle, and as a potion for detecting poison.

The Indian rhinoceros is the second largest of the five species of rhino. The African white rhino is the largest and the African black rhino is third, followed by the Sumatran rhino and the Javanese rhino. The folds in the inch-thick hide of the Indian and Sumatran rhinos make them look as if they are plated in armor. Most Asian rhinoceroses are found in India and Nepal with some in Sumatra, Java and Borneo and perhaps Vietnam, Malaysia, Myanmar Thailand, Cambodia, and Laos.

There are far fewer rhinos in Asia: only 4,100, versus 23,000 across Africa. According to Save the Rhino, as of 2022, there were 4,000 Indian rhinoceros, 35 to 50 Sumatran rhinoceros and 76 Javan rhinoceros. In recent years the population of some species has risen while for others it has declines. In the late 2000s, according to Save the Rhino there were 2,850 Indian rhinoceros, 200 Sumatran rhinoceros and 50 Javan rhinoceros. Countries where Asian rhinos are found — Indonesia, Nepal and India — have pledged to take steps to grow their rhino populations by three percent annually.

RELATED ARTICLES:

RHINOCEROSES: THEIR HISTORY, CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR factsanddetails.com

HUMANS, RHINOCEROS AND RHINO ATTACKS factsanddetails.com ;

INDIAN RHINOCEROSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND COMEBACk factsanddetails.com

JAVAN RHINOCEROS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, UJUNG KULON factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED JAVAN RHINOCEROS factsanddetails.com

SUMATRAN RHINOCEROS: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR, MATING factsanddetails.com

ENDANGERED SUMATRAN RHINOS: THREATS, GOOD AND BAD NEWS factsanddetails.com

BREEDING ENDANGERED SUMATRAN RHINOS: EFFORTS, SUCCESS, SETBACKS factsanddetails.com

Websites and Resources on Animals: International Rhino Foundation rhinos.org ; Save the Rhino International savetherhino.org; Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; BBC Earth bbcearth.com; A-Z-Animals.com a-z-animals.com; Live Science Animals livescience.com; Animal Info animalinfo.org ; World Wildlife Fund (WWF) worldwildlife.org the world’s largest independent conservation body; National Geographic National Geographic ; Endangered Animals (IUCN Red List of Threatened Species) iucnredlist.org

Rhino News: mongabay.com;

History Asian Rhinoceroses

It seems like Sumatran rhinoceroses evolved from a population of cave rhinos that ranged as far as Tibet during the Ice Age. Its seem plausible that a sub-population of these prehistoric animals migrated as far as Sumatra and eventually resided and breed there, giving birth to the Sumatran rhinoceros. The Asian one-horned rhinoceroses (the Javan rhinoceros and Indian rhinoceros) evolved from prehistoric rhinos that also produced the rhinos in Africa.

Much of the historical information about Asian rhinos is questionable as Javan and Sumatran rhinoceroses were considered the same species through the late 1800s. /=\

Rhinoceroses are large mammalian megaherbivores, As foragers, they have developed an elongated upper lip that extends out and over the bottom lip. Asian rhinoceros species possess thick folds in their gray skin, giving the illusion that the animals are wearing armor. Javan rhinoceroses has shallower skins folds than India Rhinoceroses. Both species possess a prehensile upper lip, used to pull in browse. [Source: Evan Smith, Animal Diversity Web (ADW) /=]

Indian Rhinos

The Indian rhinoceros — also called greater one-horned rhinoceros and Asian one-horned rhinoceros — and the Javanese rhinoceros are the only rhinos with one horn. The Indian species has thick, silver-brown skin which creates huge folds all over its body. Its upper legs and shoulders are covered in wart-like bumps, and it has very little body hair. Fully grown males are larger than females in the wild, weighing from 2,500 to 3,200 kilograms (5,500 to 7,100 pounds). Female Indian rhinos weigh about 1,900 kilograms. The single horn of the Indian rhino reaches a length of between 20 and 100 centimeters. Males have larger, tusklike incisors for fighting other males during the breeding season.

The Indian rhinoceros is the second largest animal in Asia after the Asian elephant. It stands at 1.75 to 2.0 meters (5.75 to 6.5 feet) at the shoulder and are three to four meters long. The largest one ever recorded weight approximately 3,800 kilograms. Its size is comparable to that of the white rhino in Africa. The Indian rhino is a creature of habit. Every evening it visits regular sites to wallow in the mud. The deeps folds in its skin create a plating effect, making the animal look as if is wearing armor, which is accentuated by tubercles (lumps), especially on the sides and rear. These resemble rivets. The pink skin within the folds is vulnerable to parasites. These are sometimes removed by egrets and tick birds. Indian rhinos have very little body hair aside from eyelashes, ear fringes and tail brush.

The Indian rhinoceros is usually found in areas of tall grass, an environment also favored by tigers. The grasses can grow as tall as eight meters high in the wet season and serve as a hiding place and a primary sources of food. These rhinos tend to feed mainly at twilight and at night, curling their upper lip around the stems to bend and bite the tend tips. They are also the most aquatic rhino. They are often seen wading or swimming, in wide rivers. A typical rhino has a territory of two to eight square kilometers, whose size is dependant on the availability of food and the quality of the habitat. Males are tolerant of intruders into their territory outside the breeding season. A single calf is usually born after a 16 month gestation period. It typically stays with the mother until her next offspring is born, which ma be three years later.

See Separate Article: INDIAN RHINOCEROSES: CHARACTERISTICS, BEHAVIOR AND COMEBACk factsanddetails.com

Javan Rhinoceros

The Javan rhinoceros is slightly smaller than the Indian rhino and a little bit larger than the Sumatran rhino. Like the closely related Indian rhinoceros, the Javan rhinoceros has a single horn. Its distinguishing features are its 26-centimeters horn and a prominent fold in the hide of its front shoulder. More than almost any other creature living today it resembles the prehistoric mammals which dominated the earth millions of years ago. [Source: Diter and Mary Plage, National Geographic, June 1985]

The Javan rhino may be the rarest large mammal on Earth. There are thought to be only around 50 of the animals left in existence, all living in the wild in Ujung Kulon National Park. There are none in captivity. Reporting from Ujung Kulon, Arlina Arshad of AFP wrote: “The shy creature, whose folds of loose skin give it the appearance of wearing armour plating, once numbered in the thousands and roamed across Southeast Asia. Officials in Ujung Kulon believe there were 51 of the rhinos in 2012, including eight calves, basing their estimate on images captured by hidden cameras. They hope the true figure may be in the 70s and will have a new estimate once data for 2013 has been collated. [Source: Arlina Arshad, AFP, December 23, 2013]

The Javan rhinoceros’s hairless, hazy gray skin falls into folds into the shoulder, back, and rump giving it an armored-like appearance. The Javan rhino's body length reaches up 3.2 meters (10 feet), including its head and stands 1.5 to 1.7 meters (4 feet, 10 inches to 5 feet 7 inches) at the shoulder. Adults are variously reported to weigh between 900 to 1,400 kilograms or 1,360 to 2,000 kilograms. Only males have true horns. Females have knobs or nothing that is visible.

Of all the rhino species, the least is known of the Javan Rhino. These animals prefer dense lowland rain forest, tall grass and reed beds that are plentiful with large floodplains and mud wallows. Javanese rhinos are very shy. They will flee their normal browsing grounds if they sense humans or animals such as oxen or deer coming near. Females give birth and raise their calves near the coast. The gestation period is 16 months. One calf is born and it is thought to saty with the mother for around two years. Sections of males home ranges usually extend to the coast. They are thought to be territorial, marking their territory with piles of dung and urine pools.

See Separate Article: JAVAN RHINOCEROS: THE WORLD'S RAREST RHINO factsanddetails.com

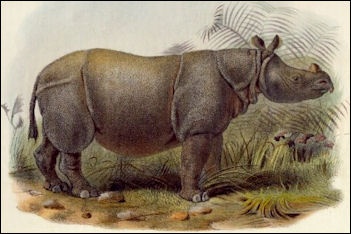

Sumatran Rhinoceros

Sumatran rhino

The Sumatran rhinoceros in the smallest and hairiest of the five rhino species. It is believed to be possibly related to the extinct woolly rhinoceros, having been around for around for 20 million years. A mature Sumatran rhino typically stands about 100 to 150 centimeters (50 to 75 inches) at the shoulder, with a body length of 240 to 315 centimeters (94 to 124 inches) and weighs around 600 to 950 kilograms (1,320 to 2,095 pounds). Like the African species, it has two horns; the larger is the front (25 to 79 centimeters), with the smaller usually less than 10 centimeters long. The males have much larger horns than the females.

Hair can range from dense (the densest hair in young calves) to scarce. The color of these rhinos is reddish brown. They have relatively few skin wrinkles except around the neck. Their body is short and has stubby legs. They also have a prehensile lip. Under ceratin conditions it will grow a thick coat of hair like that of the long-extinct woolly rhino.

Little is known about the Sumatran rhino. It is rarely seen in the wild and likes dense forests. One scientist who spent three years studying them in northern Sumatra’s Gunung Leuser National Park — one of the areas they are said to be most plentiful — only saw one once when it charged through his camp unexpectedly. Most of what is known about them has been deduced from specimens kept in captivity.

The Sumatran rhinoceros lives in both lowland and highland tropical rain forests in peninsular Malaysia, coastal areas of Sumatra, particularly in the west and south, and dense forest in very high altitudes in Sabah, Malaysia in northeast Borneo. Roaming across a grazing territory of about 16 square kilometers, it spends much of its day in wallows and browses on twigs, leaves, fruits, saplings and tender fruit. The animal is used to the shade. Captive animals exposed to long periods in the sun developed eye problems. They are pretty picky about what they eat. They prefer fresh Ficus browse. If they don’t get that they often won’t eat.

The Sumatran rhino (Dicerorhinus sumatrensis) is found in small, fragmented populations on the islands of Sumatra (Indonesia) and Borneo (Malaysia), as well as a recently identified individual or group in Indonesian Borneo. Many of these found in Sumatra live near Mount Leuser, Way Kambas and Bukit Barisan Selatan.

See Separate Article SUMATRAN RHINO factsanddetails.com

Endangered Asian Rhinoceroses

All three Asian rhino species are endangered, with two of them critically endangered: 1) The Sumatran rhinoceros is threatened by habitat loss and fragmentation, which is driven by the expansion of palm oil plantations. The use of pesticides and herbicides in these plantations can also harm the rhinos and the plants they eat. 2) The Javan rhinoceros is the most threatened of the five rhino species. There are only around 76 Javan rhinos left, and they live only in Ujung Kulon National Park in Java, Indonesia. 3) The Indian rhinoceros is threatened, but has greater numbers than the other two species. It is slowly recovering thanks to conservation efforts.

Threats to Asian rhinos include: Illegal wildlife trade, Human wildlife conflict, climate change, and inbreeding and reduced genetic diversity. According to Animal Diversity Web: The horn of the Javan rhino has been greatly sought after in many cultures. The horns of Asian rhino species are worth up to 10 times their African counterparts. The horns are used for medical purposes in Chinese remedies as a fever reducer. Other non-legitimate purposes include snake bite cures, Indian aphrodisiacs and a natural detector of poisonous substances. It is believed that the reaction occurring from poisonous substances is from the high concentration of calcium. However, no real medical values have ever been confirmed. /=\

Conservation efforts include: 1) Managed breeding; 2) In situ conservation of their habitats; 3) Supporting law-enforcement agencies to patrol rhino habitatsl 4) Working with communities to protect forested corridors used by rhinos; 5) Creating buffer zones around protected areas and 6) Reducing consumer demand for rhino horn

Growth of Nepal's Rhino Population Linked to COVID-19 Lockdowns

The population of India rhinoceroses of Nepal experienced a significant increase between 2016 and 2021 that was is likely linked, in part, to the worldwide travel restrictions placed in response to the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic. People magazine reported: “According to multiple outlets, a recent census conducted by Nepal's Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation shows that the country's one-horned rhino population increased by about 17 percent from the previous survey six years ago. The census also notes that the current one-horned rhino population in Nepal is 752 rhinos. "It's great news for all of us who care for conservation of rhinos," Deepak Kumar Kharal, the department's director-general, told the Wall Street Journal. "COVID-19 had a small but an important role helping the growth in our rhinos' population." [Source: Eric Todisco, People, April 13, 2021]

“The population of one-horned rhinos was once below 100 in the 1960s. But authorities and the government stepped up conservation efforts to boost the population and began a census every five years starting in 1994. The first census revealed there were roughly 466 rhinos in Nepal in 1994. In 2015, the census counted 645 one-horned rhinos. Per The Wall Street Journal, rangers performed the latest census, which was delayed by one year due to the pandemic, by riding on the backs of elephants for nearly three weeks in late March to count the rhinos. GPS equipment, binoculars, and cameras were all used to create the census, Phys.org reported.

“While the gestation period for rhinos is as long as 18 months, the rangers said they saw more baby rhinos than ever before and believed many survived last year due to COVID-19 lockdowns around the world, which led to a lack of tourists in jeeps. "COVID lockdown gave the best environment for the birth and growth of baby rhinos," said Bishnu Lama, a wildlife technician who worked on the census, according to the WSJ.

“According to Phys.org, the World Wildlife Fund, which provides financial and technical assistance for the census, called the rhino population increase a "milestone" for Nepal, according to Phys.org. "The overall growth in population size is indicative of ongoing protection and habitat management efforts by protected area authorities despite challenging contexts these past years," said Ghana Gurung, the WWF's Nepal representative. According to ANI News, 161 rhinos were found dead in and around Nepal's Chitwan National Park over the last five years. Five were killed by poachers, while the rest reportedly died of natural causes.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Animal Diversity Web animaldiversity.org ; National Geographic, Live Science, Natural History magazine, David Attenborough books, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, Discover magazine, The New Yorker, Time, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Wikipedia, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2024