ENDANGERED ELEPHANTS

elephant umbrella stand in Vietnam

At the turn of the 20th century there were 200,000 Asian elephants. In the 1970s there were around 150,000. Now there are between 36,000 and 51,000. Asian elephants are in a worse predicament than African elephants even though the latter get much more attention. The total population of Asian elephant is only about a tenth of the number of African elephants.

"A lot of the attention has tended to go to Africa," Simon Hedges, co-chair of the World Conservation Union (IUCN)'s Asian Elephant Specialist Group, told Reuters. “Asian elephants are somewhat the poor relation ... We really don't know how many elephants there are in Asia. In some countries we don't even know where the elephants are."

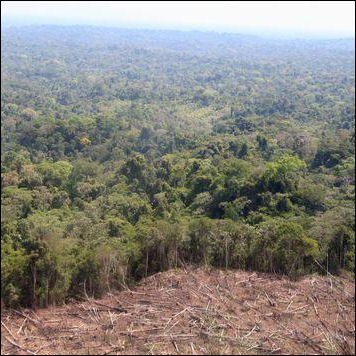

Clarence Fernandez of Reuters wrote: Across Asia, elephants are being driven from their homes as people clear forests to build houses, roads or cultivate farms, provoking often violent encounters that claim the lives of scores of humans and elephants every year. Poachers are another threat, hunting them for their tusks, meat, hair and skin. [Source: Clarence Fernandez, Reuters, March 3, 2006]

Elephant expert Cynthia Moss told the Los Angeles Times, “Asian elephants are very endangered. There are only 40,000 of them alive. African elephants, there may be as many as 400,000. But there are estimates that as many as 38,000 elephants are being killed every year by poaching and, with only 400,000 left, they could go extinct in a generation. [Source: Thomas H. Maugh II, Los Angeles Times, July 19, 2010]

Asian Elephants and Loss of Habitat

While poaching has been the greatest threat to African elephant populations, loss of habitat by human encroachment has posed the great threat to Asian elephants. These animals require huge tracts f land to feed and migrate. "The scenario is rather bleak," an Indian wildlife official told the Washington Post. "The main problem facing us today is habitat destruction. There is frequent straying into human settlements where they raid the crops and people shoot them. [Source: Washington Post]

Wild elephants are being surrounded and squeezed by human populations and threatened by the transformation of forests into farmland and commercial tea, coffee, oil palm, and rubber plantations. Centuries-old migration routes are disrupted by highways, canals and urban development; low valley habitats are flooded by dams; males are killed for their tusks. A report put out by the organization said the future of the Asian elephant is more precarious than its African counterpart because it lives in "smaller more fragmented groups."

Wide ranging elephants in many ways are more vulnerable to human encroachment than tigers, rhinoceroses and other endangered animals who tend to live in small pockets. Elephants by contrast need large areas to roam and feed in. Squeezed by loss of habitat, elephants attack villages and consume farm crops. In some cases elephants are given preference to people. Villagers who have encroached on government forest lands are driven out by police and their villages are destroyed.

Asian Elephants Illegally Taken From the Wild

Gillian Murdoch of Reuters wrote: “While tourism has become the only game in town for most of Asia's captive elephants, the industry's growth could also be a threat to dwindling wild populations, conservationists fear. "There are suggestions that elephants are being illegally caught or even being smuggled into Thailand to replace the ones that are dying," said Hedges, referring to elephants dying in camps in the north where they are used for tourist jungle treks. [Source: Gillian Murdoch, Reuters, December 23, 2007]

Once wild animals are sucked out of their forest habitats, there is little chance for "tamed" elephants to go back. Reintroducing captive elephants to forests is neither easy to do, nor a conservation priority, Hedges said. "The priority is that you work with the wild animals, and don't direct too much attention or resources to reintroduction or returning captive elephants back to the wild," he said.

The problem of illegal elephant capture and smuggling is a big problem in India. In November 2010, AP reported: Five people were arrested and three wild elephants seized as Indian police busted an elephant-smuggling ring in north-eastern Assam, officials said today. Police official PK Dutta said documents seized during the operation showed that the gang had smuggled at least 92 elephants from the north-eastern state to other parts of India over the past five years. The smugglers regularly captured wild elephants from the forests of Assam, trained them for a year or two, and then claimed they were the offspring of the state's many domestic elephants, he said.[Source: AP, November 1, 2010]

“Selling elephants is barred under Indian law and even getting permission to move domesticated elephants between states is a lengthy procedure. Nevertheless, authorities say there remains a thriving trade in elephants, with many wealthy landowners in the states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh buying the animals as status symbols. Authorities said the elephants are usually transported by truck. The smugglers are suspected of colluding with forestry officials, who have checkpoints along the major roads to prevent this type of smuggling.

Ivory

For centuries elephants have been hunted and poached for their ivory. African elephants have traditionally been a bigger source of ivory than Asian elephants because their tusks are considerably larger and have more ivory; both males and females have tusks (only male Asian elephants have them); and Asian elephants were considered more valuable as living working animals than dead sources of ivory. In some cases ivory has been taken from tusks sawed off

Most of the poached ivory found its way to Belgium, Hong Kong and Japan where ivory carvers, lathes and saws turn the raw tusks into jewelry, figurines and piano keys. One elephant tusk produces three billiard balls; two tusks provides enough ivory for a piano.

Much of the ivory in Japan is used for making signature seals, hanko, which Japanese used put their stamp on documents and papers the same way Westerners sign their names. When the Japanese economy was at its beak in the 1980s, ivory hanko were such a status symbol they primary destination of elephant tusk ivory. Forty percent of the ivory poached from Africa n the 1980s ended up in Japan, compared to 15 percent in the United States and 20 percent in Europe.←

African have always valued ivory which they say has is capable of protecting the wearers from evil spirits and curing them of illness. Ivory earrings and pendants are often adorned with dot and and circle designs that represent the "good eye." Ivory is not the only material taken from elephants. Elephant tail hair is used for making bracelets. [Source: Angela Ficher, National Geographic, November 1984]

Elephant Poaching in the 1980s

Africa's elephant population was estimated at between 5 million and 10 million before white hunters came to the continent with European colonization. In the old days elephants were sometimes hunted by encircling a herd with fire. After the animals burned to death their tusks were harvested.

Massive poaching for the ivory trade in the 1980s halved the remaining number of African elephants to about 600,000. In the decade before the 1989 ban on the ivory trade Africa’s elephant population fell from 1.3 million to 600,000. In the 15 years before the ban Kenya lost 85 per cent of its elephants.

The decline in the number of elephants has been shocking: Uganda was once the home of 20,000 elephants. In 1989 it had only 1,600. Uganda’s Kabalega Falls National Park had over 8,000 elephants in 1966. By the time unruly soldiers and heavily armed poachers were through in 1980 there were only 160 very frightened animals left. In Kenya the numbers dropped from 140,000 in 1970 to 16,000 in 1989. In the same time period there was a a decline from 250,000 animals to 61,000 in Tanzania. [Source: Douglas Chadwick, National Geographic, May 1991]

Greatly accelerating the number of elephants taken was the increased presence of firearms. In the 1980s Africa had ten times as many weapons, many of them powerful automatic rifles, than it had in the 1960s. Elephants were mercilessly killed with automatic weapons in the Idi Amin and post-Idi Amin eras in Uganda in the 1970s and 1980s. Douglas-Hamilton landed inside Uganda's Kabalega Falls National Park in 1980 and counted 78 carcasses only 58 live animals. More than 1,000 elephants were killed there. The killing was done by both soldiers loyal to Amin and those that opposed him who came afterwards. The rangers guarding the park earned six dollars a month and had only one working vehicle. ∈

Many of the poachers in Kenya's parks in the 1980s were tough bush bandits armed with AK-47 assault rifles. Chadwick helped a bloodstained German tourist onto a rescue plane after he had been shot by poachers only a mile away from where Chadwick had been watching giraffes earlier. These same poachers more or less closed down Meru National Park and Mount Elgon National Park near Uganda and made it necessary for tourists to have an armed escort.←

Elephant poachers in Thailand sometimes went after tame elephants, either killing them or stunning them with a high-voltage cattle prod, and then sawing off the tusks. Even when they stunned the elephants they might well just killed the animal, because the sometimes they sawed so close to base of the tusk root, it caused severe nerve damages and the animal died a pain death from infection.←

In Africa poachers often hacked of half of an elephant's refrigerator-size head to get at the roots of the tusks. Some carcasses look like they have been splattered with white paint as a result of the all vulture droppings. With the price of ivory running above $200 a kilograms in the 1980s and park rangers making only $20 a month it was no surprise that they participated in the poaching and even wildlife ministers reaped great sums from the ivory trade.

Consequences of Elephant Poaching in the 1980s and Efforts to Combat It

Pouching in the 1980s has led to the death of many wild elephants. Both sexes were hunted for their hides and teeth and males were especially prized for their ivory. So many males were poached in southern India that females still significantly outnumber males there.

Tsavo National Park in Kenya was devastaed by poachers. In the 1970s there were 20,000 elephants in Tsavo. By 1990 there were perhaps a thousand. Describing the decline naturalist Iain Douglas Hamilton said, "As the big tuskers disappeared , poachers turned to females. Bang! there went the reproducing part of the population — and its learned traditions involving migratory routes, dry season water sources, and so on. The whole society began to collapse. Now you see leaderless bands of sub-adults orphans. The gathering of these last groups into terrified herds of refugees. Always on the move. Poachers close behind.←

After the slaughter the elephants in Tsavo National Park fled once they got the scent of humans. Chadwick watched a group of 600 elephants feed at a water hole in Tsavo, when the wind changed and carried his scent in their direction the three million ton mass sped off into the bush as if they had seen a ghost.←

Often times the park rangers that fought the poachers were equipped World War I, bolt-action rifles while the better equipped poachers possessed AK-47s and high-powered rifles. Things changed in Kenya when Richard Leakey, son of the famous anthropologist, became head of Kenya's Wildlife Service in 1989. He outfit his anti-poaching units not only automatic weapons, but also witj helicopter gunships and shoot to kill orders. As of 1991 over a 100 poachers had been killed.←

In a dramatic move that received quite a bit of publicity worldwide Kenya's president Daniel arap Moi gave the order to burn over 2,500 elephant turks, worth an estimated $3 million.

Ivory Ban and Containment of Elephant Poaching

In 1989, after sharp declines of elephant populations in Africa, with most of the animals poached for their ivory, a worldwide ivory ban was imposed that was agreed upon by 105 of 110 nation members of the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES).

The ivory ban, aggressive anti-poaching measures and media attention on the plight of elephants were largely successful in helping to restore elephant populations in Africa but had less impact on Asian elephants. Demand for ivory and the price of ivory has dropped, and there less incentive for poachers to kill elephants.

Following the 1989 ban on ivory trade and concerted international efforts to protect the animals, elephant herds in east and southern Africa made a dramatic come back. The number of elephants in Kenya increased 60 percent — from 16,000 to 26,000 animals — between 1989 and 1993. The elephant population in Kenya stabilized at around 25,000 and the number of poaching deaths was reduced from 3,000 in 1989 to 20 in 1994. [Source: Susan Okie, Washington Post, December 27, 1993]

Poaching was not a big problem in the 1990s and early 2000s but it continues. Many countries were overrun with elephants. Malawi, Zambia, South Africa, Botswana and Zimbabwe had herds that were so large the animals had to be culled to prevent destruction of the land. Elephants tore down trees, trampled fields and generally made a nuisance of themselves. Park rangers wanted to cull the elephant herds and use money generated from ivory sales to finance wildlife programs.

End of the Ivory Ban

In June 1997, at a CITES meeting elephants were taken of the endangered list in a secret-ballot and the eight-year ivory ban was ended in Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe, allowing these countries sell stockpiled ivory as well as elephant meat and hides and live elephants to zoos. According to the deal all their stockpiled ivory (maybe 120 tons) in those countries was sold to Japan in a tightly controlled operation to make sure no poached ivory entered the market. Worldwide the estimated of stockpiles ivory in 1996 were as high as 500 to 600 tons.

At that time there was a stable population of around 150,00 elephants in Botswana, Namibia and Zimbabwe. Many conservationists went along with the controversial proposals because money raised from the ivory sales was directed to animal conservation and payments to farmers and villagers that live around wild animals to provide them with compensation for lost animals and revenues from tourism and hunting to help them develop an interest in preserving the animals.

Botswana president Ketumil Masire called efforts by Western nations to the control animals in African countries "environmental imperialism." An Namibian official told the Washington Post, there is a "distorted relationships between people and wildlife, in industrialized countries, where Babaar and Dumbo, are more real than the real thing."

Critics of the ivory ban claimed that while elephant herds in Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia were healthy, the end of the ban might encourage poaching in central, western and eastern Africa where elephants population were endangered and vulnerable to poaching. In an attempt to distinguish between ivory from poached elephants and ivory from legally killed animals, scientists tranquilizing elephants and took their DNA "finger prints" so they could tell the difference between culled animals in Zimbabwe and poached ones in Kenya. [National Geographic Earth Almanac, November 1993].

Elephant Poaching in the 2000s

In estimated 257 tons of ivory was taken from poached elephants in 2006. About 23,000 killed elephants are necessary to produce that much ivory, The cost of ivory was around $800 a kilogram that year up from $110 a kilograms in the 1980s.

Tristan McConnell wrote in The Times, “Kenya recorded its worst year for killing in decades in 2009, with 249 elephants killed, up from 140 in 2008 and just 47 in 2007. Last year the killing continued across the continent, the ivory smuggled out of the country as raw tusks or carved ornaments to be sold on the Far East black market. [Source: Tristan McConnell, Times of London, January 8, 2011]

Prices for ivory are so high that fears are growing of a return to the devastation of the 1970s and 1980s. “The rewards are such that you inevitably run into corruption issues,” said Peter Younger, the wildlife crime programme manager at Interpol, who has helped in stings on ivory trafficking gangs. Charlie Mayhew, of Tusk Trust, said: “Prices are so high there are rewards for everyone ... from rangers all the way to politicians....What we are seeing now is more worrying [than the 1980s] because the bans are in place yet poaching is escalating. The gains of the last ten years can be quickly eroded.”

Dr Richard Leakey, a naturalist, added: “We’re right back where we were in the 1980s. I suspect that a lot of the killing in Kenya is carried out by wildlife department personnel or with their full connivance.” Julius Kipngetich denied collusion by his department’s officials saying, “If you look at the seizures it is clear they are not coming from government stocks because those are marked with indelible ink.”

Ian Craig, the chief executive of the Northern Rangelands Trust, a conservation group working to the north of Mount Kenya, has found 23 elephant carcasses in the last few weeks, all with their tusks hacked off. “I’d say that we’ve reached perhaps a ten-year high in our area. Demand is up, prices are up; there are a lot of guns and a lot of criminals,” he said.

Income from the ivory trade provided money to groups like the Janjaweed, which behind much of the violence and ethnic cleansing in the Darfur area of Sudan.

2011 Worst Year in Decades for Endangered Elephants

In December 2011, AP reported: “Large seizures of elephant tusks make this year the worst on record since ivory sales were banned in 1989, with recent estimates suggesting as many as 3,000 elephants were killed by poachers, experts said Thursday. "2011 has truly been a horrible year for elephants," said Tom Milliken, elephant and rhino expert for the wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC. "In 23 years of compiling ivory seizure data ... this is the worst year ever for large ivory seizures," said Milliken. [Source: Associated Press, December 29, 2011]

Some of the seized tusks came from old stockpiles, the elephants having been killed years ago. But the International Fund for Animal Welfare said recent estimates suggest more than 3,000 elephants have been killed for their ivory in the past year alone. "Reports from Central Africa are particularly alarming and suggest that if current levels of poaching are sustained, some countries, such as Chad, could potentially lose their elephant populations in the very near future," said Jason Bell, director of the elephant program for the fund based in Yarmouth Port, Massachusetts He said poaching also had reached "alarming levels" in Congo, northern Kenya, southern Tanzania and northern Mozambique.

Milliken thinks criminals may have the upper hand in the war to save rare and endangered animals. "As most large-scale ivory seizures fail to result in any arrests, I fear the criminals are winning," he said. TRAFFIC said it is clear there's been a "dramatic increase" this year in the number of large-scale seizures -- those over 1,760 lbs. in weight. There were at least 13 large seizures this year, compared to six in 2010 with a total weight just under 2,200 lbs. In Tanzania's Selous Game Reserve alone, some 50 elephants a month are being killed and their tusks hacked off, according to the Washington-based Environmental Investigation Agency.

With shipments so large, criminals have taken to shipping them by sea instead of by air, falsifying documents with the help of corrupt officials, monitors said. In another sign of corruption, Milliken said some of the seized ivory has been identified as coming from government-owned stockpiles -- made up of both confiscated tusks and those from dead elephants.

Asia Fuels Record Killing of Elephants in Africa

In December 2011, AP reported: Most cases of ivory smuggling “involve ivory being smuggled from Africa into Asia. TRAFFIC said Asian crime syndicates are increasingly involved in poaching and the illegal ivory trade across Africa, a trend that coincides with growing Asian investment on the continent. "The escalation in ivory trade and elephant and rhino killing is being driven by the Asian syndicates that are now firmly enmeshed within African societies," Milliken said in a telephone interview from his base in Zimbabwe. "There are more Asians than ever before in the history of the continent, and this is one of the repercussions." [Source: Associated Press, December 29, 2011]

In July 2012, AFP reported: “China, Vietnam and Thailand are among the worst offenders in fuelling a global black market that is seeing record numbers of elephants killed in Africa, environment group WWF said. Releasing a report rating countries' efforts at stopping the trade in endangered species, WWF said elephant poaching was at crisis levels in central Africa. In parts of Asia, elephants' ivory has for centuries been regarded as a precious decoration.[Source: AFP, July 23, 2012]

Global efforts to stem the trade have been under way for years, but China, Thailand and Vietnam are allowing black markets in various endangered species to flourish by failing to adequately police key areas, according to WWF. The WWF it accused China and Thailand of being among the worst culprits in allowing the illegal trade of elephant tusks. "Tens of thousands of African elephants are being killed by poachers each year for their tusks, and China and Thailand are top destinations for illegal African ivory," WWF said.

WWF urged China to improve its enforcement procedures and warn Chinese nationals they would face severe penalties if they were caught illegally importing ivory from Africa. China has also made genuine efforts overall to stop the illegal trade of endangered species' parts, but elephants' ivory remained a big problem because of the huge demand in the world's most populous country, it said.

In Thailand, WWF said the main problem was a unique law that allowed the legal trade in ivory from domesticated elephants. In reality, this was a "legal loophole" that allowed indistinguishable illegal African ivory to be sold openly in upscale boutiques, it said.

China and Elephant Poaching in Africa in the 2000s

Frank Pope wrote in the Times of London in 2011, “Africa is facing its worst elephant poaching crisis for decades with bulls being slaughtered illegally to meet the demand for ivory from China’s nouveau riche. Even in one of the continent’s best protected reserves, the Samburu National Park in northern Kenya, more elephants have been lost in the past two and a half years than in the previous 11. During the last five months, the level of poaching has been the worst on record. [Source: Frank Pope, Times of London, August 2011]

“Even within well-protected, closely monitored populations, bull elephants and matriarchs are being targeted for their large tusks — skewing sex ratios and leaving leaderless herds of orphans,” said Dr Iain Douglas-Hamilton, the founder of Save the Elephants, a research organisation based in Samburu. Last year, 30,000 elephants were poached from just one reserve, Selous, in Tanzania.

“Dr Cynthia Moss, an elephant zoologist at the Amboseli reserve in Kenya, is certain that a decision by the UN’s Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (Cites) to relax a 20-year ban on the ivory trade is to blame. “In 2008, Cites allowed China to buy ivory from a stockpile, and in early 2009 — for the first time in 20 years — we started seeing poaching,” she said. Demand from China’s nouveaux riche has driven the price of ivory to $700 a pound or more, which has encouraged poachers all the more. “If the 200 to 300 million affluent, middle-class Chinese chose ivory as a fashion item, then it could destroy a large part of Africa’s elephants,” Douglas-Hamilton said.

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Vanity Fair, “The previous slaughter was driven by Japan’s economic boom. This new crisis is driven by China’s or bao fa hu (the “suddenly wealthy”), who are as numerous as the entire population of Japan. The main consumers are middle-aged men who have just made it into the middle class and are eager to flaunt their ability to make expensive discretionary purchases. Beautiful ivory carvings are traditional symbols of wealth and status. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair, August 2011]

“Crystal,” a Chinese undercover investigator for the IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare) told Vanity Fair, “Elephants are a global priorityTigers are an Asian priority, and we are trying to do something for the stray cats. China has no animal-welfare laws.” Although the killing of a panda or an elephant was a capital offense until last year. There are only a few hundred wild elephants in China, all of them in the extreme south of Yunnan Province, near the Laos and Burma borders. They are the Asian species, Elephas maximus, of which there are around 50,000 left — about one-tenth of the African population. Most of them are in India, and their annual mortality from poaching comes to only 300 or 400.

Ivory Market in Hong Kong

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Vanity Fair, “In the corridor leading from my plane to the formalities in Hong Kong International Airport, there is a display cabinet of forbidden wildlife products, including a hawksbill-turtle shell and an elaborately carved elephant tusk. But this isn’t stopping Hong Kong and adjacent Macao from being two of the main destinations for African ivory. A few days ago 2,200 pounds of ivory were seized on the beach of the Westin hotel in Macao. Using the commonly accepted figure of 12.6 pounds for the average pair of tusks, that would be 175 elephants. An average 45,000 pounds of ivory a year have been seized in the past decade. Using Interpol’s 10 percent estimate, which is based on the amount of drugs they believe they are intercepting — meaning 90 percent gets past them — that would be 450,000 pounds, or more than 35,000 elephants a year. So IFAW’s 36,500-a-year estimate, 100 a day, is definitely possible. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair, August 2011]

In the shopping arcade of the hotel where I am staying, there are a few bangles identified as “genuine ivory” for sale. Their prices range from $200 to $600. “I thought ivory was banned,” I tell the saleswoman. “This is a free port. You can buy whatever you want,” she says. “But there’s a display at the airport that says it’s forbidden,” I say, and the woman, shamelessly quick on her feet, says, “Well, yes, African ivory is. But this is mammoth ivory. Status fine.” But the bangles are pure, creamy white, unlike mammoth ivory, which is nut-colored or streaky — this is unquestionably savanna ivory from Africa.

Ivory Market in Guangzhou

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Vanity Fair, “I take the evening train to Guangzhou, a big wholesale city and a mecca for thousands of African traders, who buy apparel and footwear to take back home to sell in Dakar or Kinshasa. The three men sitting next to me are Congolese. Guangzhou has a growing population of eight million people, and thickets of brand-new high-rises with kitschy pagodas on their roofs and lots of neon signage. It’s like Disney World, this crass new capitalist China. You can feel the economic vibrance and might of the next global superpower. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair, August 2011]

The next morning Crystal and I go to a jade store in the Liwan District to see if there are any ivory hanko. Hanko are the signature seals that documents in China and Japan are traditionally stamped with. The seals in Japan are round; in China they are square. Japanese tourists fly to Hong Kong or Shanghai for the weekend, where ivory is cheaper, and pick up a cylinder of ivory and take it back to a Japanese hanko shop that will then carve their seal. There are plenty of perfectly good substitutes, like ox bone or wood, but ivory hanko have cachet. It’s like owning a Mont Blanc pen.

The salesman tells us there is strict government control of ivory. “We can’t sell ivory publicly, but” — his voice lowers—“I have a friend who can do it. How many hanko you want?” We continue to the Hualin Street wholesale jade market, which has all kinds of beautiful stuff, not only jade. Contraband wildlife artifacts are openly displayed. One stall has hawksbill-turtle-shell eyeglass frames and combs. In another the man shows us two ivory bangles, a tiny abacus, a little Buddha, and a small tusk carved with a cabbage-leaf motif. He has his own factory in Fujian Province. The ivory comes from Africa by ship to a port near Taiwan. With a little coaxing he brings out the big stuff, wrapped in plastic: a two-foot-long tusk with the cabbage-leaf design for 28,000 yuan (a little more than $4,000).

“Do they have to kill the elephant?,” I ask him.”No,” he says. “After you get the ivory, teeth grow again, just like human teeth.”In the morning I say good-bye to Crystal. “You will see many changes in your lifetime,” I tell her. “China will have taken over the world, and maybe there will be no more elephants.” “I will never let that happen,” she promises me.

Forces Behind the Ivory Market in China

Elephant expert Cynthia Moss told the Los Angeles Times, “There's a big demand in China now, where there has never been before. China has been the carver's site, but (the Chinese) didn't buy it themselves. Now, with the growing middle class, they want ivory ornaments, jewelry, things like that, and so there is a huge demand.” Yhe Chinese government “petitioned to become one of the legal buyers of ivory (from carcasses, confiscated ivory, etc.) and they got that permission the year before last. They've definitely encouraged ivory, because they've encouraged the ivory factories to open again. And of course, there is not enough (legal) ivory for the carvers. So it's very unfortunate they were given permission. [Source: Thomas H. Maugh II, Los Angeles Times, July 19, 2010]

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Vanity Fair, “In Guangzhou there are markets that specialize in wild-animal meat like snakes and rats, and there’s a special cat market. You pick the cat you want to eat, then they kill it and sell you the meat. There’s a saying that the southern Chinese will eat anything with legs except a table, and anything with wings except a plane. I’ve been hearing that this is also now a problem with the Chinese in Africa — and not only those from the South — who are eating domestic dogs and cats, baboons, painted dogs, and leopard tortoises and making soup from the marrow of lower leg bones of giraffes and from lion bones. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair, August 2011]

Grace Ge Gabriel, Crystal’s boss in Beijing, laments, “Chinese society today is ruled by one principle only: Make Money for Me. On the way to make riches for oneself, there is no concern for anything, including other people and the environment, let alone animals. Unfortunately, the south-Chinese practice of “eating everything in sight” is adopted by a lot more people now. And the Chinese have the ability to travel all over the world now. Especially in countries where law and order are not well established, these Chinese feel that they can get away with eating anything and everything.”

“Another problem,” Crystal explains, “is that the Chinese word for ivory is elephant’s teeth — xiang ya. We did a survey. Seventy percent thought tusks can fall out and be collected by traders and grow back, that getting ivory did not mean the elephant is killed, and more than 80 percent would reject ivory products and not buy any more if they knew elephants were being killed, so it’s ignorance.”But the same survey found reluctance to comply with the ivory-control system and a desire for “affordable” ivory. Fourteen and a half percent of those polled were already ivory consumers, and 76 percent were willing to break the law to buy ivory at a cheaper price. Liwan District, Guangzhou

Chinese Ivory Network

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Vanity Fair in 2011, “In the first week of May alone, a ton of ivory was confiscated in Kenya, more than 1,300 pounds in Vietnam — from Tanzania — and a Chinese man was arrested at Entebbe airport in Uganda with 34 pieces of ivory. To top it off, a South Korean diplomat was caught trying to bring 16 tusks into Seoul. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair, August 2011]

Once ivory gets to Nairobi and is ready to be shipped, the Chinese involvement becomes traceable. Hundreds of thousands of Chinese workers and other temporary laborers are employed on road, logging, mining, and oil-drilling crews in all of the elephants’ range states. Some manage to make it home with a few pounds of ivory hidden in their suitcases, thus doubling their meager earnings, or they are recruited as carriers for higher-ups. But they are not the real problem. The real problem is the managers, who have the resources to directly commission some local to kill an elephant and bring them the tusks, and diplomats, whose bags are not checked, and the Chinese businessmen, who are taking over the economy of Africa.

In the last decade the number of Chinese residents in Africa has grown from 70,000 to more than a million. China’s trade on the continent — $114 billion last year — is expected to keep increasing by over 40 percent a year. According to Traffic, a nonprofit wildlife-trade-monitoring network, each day, somewhere in the world, an average of two Chinese nationals are arrested with ivory.

Back to the tusks. Maybe the smugglers deliver them to Mombasa. K.W.S. knows the networks. Once there, little boats come from big ships offshore to private wharves of local “tycoons” with heroin and guns and return with ivory. The drug, arms, money-laundering, and ivory trades are intertwined, K.W.S.”s Julius Kipng’etich told me. Where you have one, you have the others. Once on the big ship, the ivory is hidden in shipping containers with legal consignments like sisal (the fibrous agave that twine is made from), avocados, or pottery.

All over Africa, ivory from freshly killed elephants is being put on planes or ships and is hopscotching around the Middle East and Asia: to Beirut, Dubai, Bangkok (the big hub at the moment), Taipei, Vietnam, Singapore, Kuala Lumpur, Shanghai, Hong Kong, Macao. One consignment hidden in sisal made it all the way from Tanzania to the Philippines and was sent from there to Taiwan, whose customs thought, Sisal from Tanzania going to the Philippines, the world capital of sisal production? That’s like importing oranges to Florida. So they opened the crates, and there were 484 pieces of ivory.

Once a shipment leaves Africa, it never goes directly to the final destination. The routes are constantly changing. It’s a shell game, as Wasser says. But eventually most of the ivory arrives, by land, sea, air, or a combination thereof, in Guangzhou, formerly Canton, China’s main ivory-carving-and-trading center, just up the coast from Hong Kong. All roads lead to Guangzhou. There are around 100 master carvers in this humming city of eight million. Most of them are working in illegal factories. But there are also legal, state-owned factories, which get their ivory from the one-off sales of old stock that CITES allowed South Africa, Botswana, Namibia, and Zimbabwe to have in 2008. These sales supplied 100 tons of ivory to the Chinese and Japanese markets. The argument for allowing them to happen was that China and Japan would be happy with so much ivory, and the poaching would be reduced, but they have had the opposite effect: the poaching has been showing a steady rise, and a lot of illegal ivory is being passed off as old stock.

China and Elephant Poaching in Kenya

Tristan McConnell wrote in The Times, “Authorities in Kenya, where at least 178 elephants and 21 rhinos were killed in 2010, attribute the rise in poaching to unprecedented interest in ivory from the Far East and the increasing presence of Chinese employees in Kenya. [Source: Tristan McConnell, Times of London, January 8, 2011]

According to the Kenya Wildlife Service (KWS) experts, the vast majority of those arrested for trafficking horns and tusks are Chinese. Dr Julius Kipng’etich, the director of KWS, said, “It is not a myth or a theory, it is a reality. Ninety per cent of all the people who pass through our airports and are apprehended with illegal wildlife trophies are Chinese.” Most of these “trophies” consist of ivory parts. Richard Leakey, the renowned Kenyan conservationist and former head of the National Wildlife Authority, said, “All the pointers are that poaching has grown very rapidly, very recently.”

A leaked embassy cable written by Michael Ranneberger, the US Ambassador to Kenya, in February and published recently by the website WikiLeaks said: “KWS noticed a marked increase in poaching wherever Chinese labour camps were located and in fact set up specific interdiction efforts aimed to reduce poaching. “The [Government of China] has not demonstrated any commitment to curb ivory poaching. The slaughter of the animals has left conservationists dismayed and worried for the survival of the species.”

Chinese Infrastructure Projects and the Ivory Network

Poaching for ivory has risen over the past three years in Tanzania, Kenya, Zimbabwe, South Africa and the Democratic Republic of Congo. China is investing billions in Africa every year in deals that swap roads and railways for the minerals and natural resources that fuel its growing economy. The increasing number of Chinese-led infrastructure projects in eastern Africa have provided a ready supply of middlemen willing to send ivory eastwards, according to Esmond Martin, an ivory trade expert. [Source: Frank Pope, Times of London, August 2011]

Charlie Mayhew, the chief executive of the UK-based conservation group Tusk said, “There has been a massive investment in Africa by China and that has resulted in a significant Chinese presence of workers and businessmen across the continent.” Tom Milliken, regional director for east and southern Africa at Traffic, which monitors wildlife trade, said, “China is the major driver for trade in ivory and that is linked to China’s phenomenal economic growth, the level of disposable income there, a re-embracing of traditional culture and status symbols in which ivory plays a role, and the phenomenal increase of Chinese nationals on the African continent.”

Alex Shoumatoff wrote in Vanity Fair in 2011, “Ninety percent of the passengers who are being arrested for possession of ivory at Jomo Kenyatta are Chinese nationals, and half the poaching in Kenya is happening within 20 miles of one of the five massive Chinese road-building projects in various stages of completion. [Source: Alex Shoumatoff, Vanity Fair, August 2011]

There had been almost no poaching around Amboseli for 30 years before a Chinese company got the contract to build a 70-mile-long highway just above the park. Since the road crews arrived, in 2009, four of Amboseli’s magnificent big-tusked bulls have been killed, and the latest word is that the poachers are now going after the matriarchs — a social and genetic disaster, because elephants live in matriarchies, and removing the best breeders of both sexes from the gene pool could funnel the Amboseli population into what is known as an “extinction vortex.”

The Amboseli Trust for Elephants said: “There are two Chinese road camps in the general area,” the Trust reported, “We are told by our informants that they are buying ivory [and] bushmeat.”

Ivory Seizures in Asia

In December 2011, Malaysian authorities seized hundreds of African elephant tusks worth $1.3 million that were being shipped to Cambodia. The ivory was hidden in containers of Kenyan handicrafts. Customs officials in Malaysia made three major seizures, uncovering thousands of elephant tusks.

In October 2011, AP reported: “Vietnamese authorities say they have uncovered more than a ton of elephant tusks that smugglers were attempting to illegally take to China.Customs official Ly Tran Tuan says the 221 pieces of tusks were discovered hidden in rolls of fabric that were being transported on a boat on the Ka Long river bordering the two countries. Tuan said Monday that a Chinese man who was escorting the boat and the Vietnamese captain were detained by local police for further investigation.Vietnam bans the hunting of its dwindling elephant population. In 2009, authorities confiscated nearly 7 tons of elephant tusks smuggled from Tanzania in the country's biggest ivory seizure. Tusks are used for ivory jewelry and home decorations. [Source: AP, October 23, 2011]

In one week alone authorities in Thailand, a favoured transit point for the illegal trafficking, said they had seized 69 elephant tusks and four smaller pieces of ivory smuggled in from Mozambique and worth more than £190,000. “The situation is not hopeless but this is a war and our efforts at the moment equate to a triage,” said Meredith Ogilvie-Thompson, Tusk’s recently appointed Executive Director in the USA. Elephant ivory worth more than £64 per kg to poachers in Africa goes for ten times that price in China. [Source: Tristan McConnell, Times of London, January 8, 2011]

Ivory Seizures in Hong Kong

In 2006, a ship that sailed from Cameroon to Hong Kong was found to ave three containers with false bottoms, each filled with ivory. According to Newsweek the compartments had been “deftly camouflaged with sophisticated metallurgy.” The suspected trafficker, a Taiwanese, was not extradited because of Taiwan’s diplomatic isolation. The trafficker is believed to have sent 40 tons of ivory, from an estimated 4,000 killed elephants, along the same route in shipments labled “timber planks.” DNA tests indicated the elephant came from Gabon and the Congo. [Source: Newsweek, March 10, 2008]

In November 2011, the New York Times reported: “Authorities at the Hong Kong International Airport 33 rhino horns, 758 ivory chopsticks, and 127 ivory bracelets concealed inside a shipping container from Cape Town, South Africa. The concealed animal parts were labeled as “scrap plastic,” an increasingly common trick for smuggling horns and ivory out of Africa and into Asia. [Source: Rachel Nuwer, New York Times, November 21, 2011] Tom Milliken, a program coordinator at Traffic, a wildlife trade monitoring network, said the ivory was likely bound for Guangzhou, China, where the largest waste processing industry in the world is located. “Unfortunately, Guangzhou also has a very large ivory carving industry,” he said.

In August 2011 AP reported: “Hong Kong customs officers have seized a large shipment of African ivory hidden in a container that arrived by sea from Malaysia. Hong Kong government officials said on Tuesday that officers found 794 pieces of ivory tusks estimated to be worth $HK13 million ($1.5 million).The officers found the tusks, which were hidden by stones, on Monday after deciding to examine the shipment, which the officials said was labelled "nonferrous products for factory use". [Source: AP, August 31, 2011]

The container arrived from Malaysia, but the officials did not say where it originated from. A 66-year-old man was arrested and officials are investigating. Wildlife trade monitoring network TRAFFIC said the shipment appeared destined for China, which it considers the leading driver of African poaching. A few weeks before 1041 tusks were seized on the island of Zanzibar, concealed in a container of anchovies destined for Malaysia, an important transit point for ivory smuggling.

Combating Ivory Poaching

Clarence Fernandez of Reuters wrote: “To try and curb the trade, Thailand began implanting microchips in domesticated elephants five years ago in a project that has so far installed the devices in 70 percent of the country’s 2,350 domesticated elephants. “Microchips help us to differentiate wild from domesticated elephants,” said Prasop Tipprasert, a specialist at the National Elephant Institute that runs the project jointly with the Department of Livestock Development and Mahidol University. “When we run across an elephant with no chip, our first suspicion is the animal was taken from the wild. This is an effort to deter wild elephant poaching,” he told Reuters. [Source: Clarence Fernandez, Reuters, March 3, 2006]

Former Chinese NBA basketball player Yao Ming has become an activist and conservationist intent on weaning the Chinese off their fondness for rhino horn, elephant ivory and shark fin soup. He has visited Kenya to raise awareness about the rhino horn and ivory issues and made a film there called “End of the Wild.”

Peter Knights, director of WildAid, an organization that uses Chinese celebrities, like Ming and Jackie Chan, to encourage Chinese not to buy ivory, told Vanity Fair, “It’s a combination of new money and old ideas, a huge bubble we’re trying to burst. The younger generation gets it. It’s the aging new wealthy, who have tremendous purchasing power and see acquiring ivory as part of holding on to their historic Chinese-ness, who have to be reached — before there’s no more ivory left to buy.” Knights told Vanity Fair the Chinese government has been very supportive. CCTV, the state-owned television station, and a whole range of other outlets have donated media time and aired everything from 15- to 30-second public-service announcements to five-minute shorts to half-hour documentaries.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, Natural History magazine, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, The Economist, BBC, and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2012