ORANGUTANS

Orangutans are among the rarest of all apes. Wild ones can only be found on the islands of Sumatra and Borneo in Indonesia and Malaysia. Highly intelligent, their close-set eyes and facial expressions make them look eerily human. The Dyaks consider orangutans to be the equals of humans, and they are treated with the same respect as neighboring tribes. Orangutans are still respected in Indonesia and Malaysia, where they pictured on some paper money and coins. Orangutan is Malay for "person of the forest." [Sources: Biruté Galdikas, National Geographic, October 1975; June 1980; October 1985; Eugene Linden, National Geographic, March 1992; Cherly Knott, National Geographic, August 1998; “Reflections of Eden” by Biruté Galdikas]

Orangutans are apes rather than monkeys and the largest creatures found in the canopy of the rain forest or far that matter are the largest animal period that lives in trees (gorillas are larger but they generally don’t live in trees). Although they have human-like expressions and sometimes display human like-behavior they are regarded as less closely related to humans than gorillas or chimpanzees.

Orangutan researcher Biruté Galdikas told Smithsonian magazine “orangutans are tough. They're flexible. They're intelligent. They're adaptable. They can be on the ground. They can be in the canopy. I mean, they are basically big enough to not really have to worry about predators with the possible exception of tigers, maybe snow leopards. So if there were no people around, orangutans would be doing extremely well." [Source: Bill Brubaker, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010]

Around 50,000 to 60,000 orangutans are left in the wild, with about 90 percent of them in Indonesia . Today an estimated 48,000 orangutans live in Borneo and another 6,500 in Sumatra. About half the orangutans that live on Borneo live peat-swamp forests in Central Kalimantan and the forest in East Kalimantan and Sabah. In the old days orangutans could range across the entire island of Borneo but most live in small, scattered populations.

There are 30 percent less orangutans than there were in the 1980s. As recently as 1900, more than 300,000 orangutans roamed freely across the jungles of Southeast Asia and southern China A few decades ago there were still hundreds of thousands of them.

In the early 2000s it was said there were around 15,000 to 24,000 orangutans are left in the wild. The number was upped to around 40,000 after studies in 2004. A new population with several thousand members was discovered in Kalimantan. There are about 1,000 in captivity.

Orangutan Subspecies

Bornean orangutan

There are two subspecies of orangutan: those originating from Sumatra, and those from Borneo. The two populations have been isolated for more than a million years and are now considered by many to be separate species; the Bornean orangutans are slightly larger than the Sumatran variety. The population in southwestern Borneo, some scientists say, is different enough from others found elsewhere on the island to warrant classifications into a third subspecies.

It is not easy to tell the two subspecies (species) apart. The most pronounced difference is between adult males. Bornean males tend to have larger cheek pads, rounder faces and darker fur while Sumatran males have more whiskers around their cheeks and chins and curlier, more matted hair on their body.

There is also significant genetic differences between the two subspecies. Part of the second chromosome on one species is flipped in relationship to the second chromosome of the other.

The two subspecies diverged at least 20,000 years when Ice-Age-caused land bridges between Sumatra and Borneo were covered up by rising sea water as the Ice Age ended. The genetic evidence seems to indicate the two subspecies were separate hundreds of thousands of years before that. Fossil evidence also indicates that orangutans once lived in southern China, northern Vietnam, Laos and Java and were there until relatively recently.

Orangutan History

Sumatran orangutan

The earliest human ancestor so far discovered is a 33 million year old arboreal animal nicknamed the "dawn ape" found in the Egypt's Faiyum Depression. This fruit-eating creature weighed about eight pounds (three kilograms) and had a lemur-like nose, monkey-like limbs and the same number of teeth (32) as apes and modern man.

About 25 million years ago the line that would eventually lead to apes split from the old world monkeys. Between 20 million and 14 million years ago orangutans split off from the other “great apes,” chimpanzees, gorillas and humans. Between 14 million and 5 million years ago numerous species of early apes spread across Asia, Europe and Africa.

In a June 2007 article in the journal Science, Susannah Thorpe and Roger Holder of the University of Birmingham and Robin Crompton of the University of Liverpool suggested that bipedalism arose much earlier than previously thought among arboreal apes — perhaps as early as between 17 million and 24 million years ago — based on the way wild orangutans navigate their way along fragile tree branches. Thorpe spent a year observing wild orangutans in the forest of Sumatra and saw them walk on two legs on fragile branches to reach fruit, using their arms to keep balance or grasp for fruit while using all four limbs on bigger branches. The finding is significant in that it shows bipedalism might have first evolved as a way to move around in the trees rather than on the ground.

Thorpe spent a year in Indonesia's Sumatran rain forest painstakingly recording the movements of the orangutans. "I followed them from when they woke up in the morning to when they made their night nest in the evening," Thorpe told Reuters. "Our results are important because we have shown how bipedalism could have evolved in the original ape habitat, to navigate the very smallest branches where the tasty fruits are, and the smallest gaps between tree crowns.” [Source: Will Dunham, Reuters, May 31, 2007]

"As the only great ape which remains in the ancestral ape niche (arboreal fruit eaters), orangutans are therefore a vital model for the understanding of the evolution of limb adaptation in apes," Crompton said. The researchers said as the rain forest in eastern and central Africa receded due to climate changes near the close of the Miocene epoch, which ended 5 million years ago, arboreal apes that already had acquired the ability to walk on two legs were forced to spend more time on the ground. They proposed that apes in the evolutionary line that led to people descended to the ground, remaining bipedal. [Ibid]

On seeing an orangutan named Jenny at the London Zoo in 1842, Queen Victoria, declared the beast "frightful and painfully and disagreeably human."

Orangutan Characteristics

Both sexes of orangutans can live 30 to 50 years in the wild. Orangutans hold the longevity record for non-human primates. A pair of orangutan that died in 1976 and 1977 after 48 and 49 years in captivity were believed to be 58 and 59 when they died. In 2008, the oldest orangutan at that time — a Sumatran orangutan named Nonja — choked to death on her own vomit at the 55 at the Miami Metro Zoo after suffering a brain hemorrhage.

Large males in the wild weigh up to 300 pounds, reach a height of 5½ feet, and have an arm span of seven feet. The largest on record was almost six feet tall. Females weigh about half as much. In captivity they can get quite fat. Some males in zoos have tipped the scales at over 200 kilograms.

Orangutan arms and hands are almost twice as long as their legs and feet and reach down to their ankles when the animal stands erect. The legs are short and weak. Although they have a body weight comparable to that of humans, orangutans can be four times stronger. German zoologist Peter Pratje, who was once attacked by a slightly smaller orangutan, told the Los Angeles Times he has calculated that a 140-pound orangutan is twice as strong as Arnold Schwarzenegger.

Orangutans adults have cheek pads and they are especially pronounced in older males 12 years old and older. The cheeks are comprised of fat covered by skin with only a minimal amount of hair. Older males acquire bulging, fatty cheek pads and throat sacs. Healthy males have tight extended face pads. Shriveled cheek pads indicate poor health.

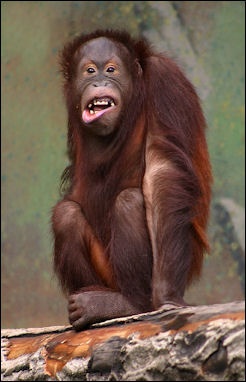

Orangutans have white around the irises in their eyes like humans. Unlike chimpanzees and gorillas they have don’t have pronounced brow ridges. Their powerful jaws and spadelike incisors can rip apart and tear through tough fruit skins and nuts. The grip of their powerful hands is strong enough to crush the bones in your hands. Their unusually flexible mouths are capable of making a wide range of expressions and noises.

Orangutan Characteristics for Life in the Trees

Orangutan have powerful arms, which are used for climbing and swinging. Their hook-like hands allow them to move through high canopy by keeping contact with the limbs at all times and also allow them to hang freely and comfortably from trees and even sleep in this position. The use their weight to sway saplings back and forth to reach their next destination. Even their legs are adapted to walking on branches rather on the ground. When they walk on the ground they do so on all fours with clenched fists (not knuckles like gorillas and chimpanzees).

Orangutan spend almost all their time in the trees and are the only true tree-dwelling ape. The only time that they walk on the ground is to get from one tree to another and occasionally to forage. Because they are so big they have difficulty moving from one tree to another and often descend down one tree to the ground and ascend another using a liana, climbing hand over hand. One reason that orangutans survive better in primary forests rather than secondary ones is that they can move round better on big trees.

The thin and shaggy, dark rufous to reddish brown fur serves as camouflage. Biruté Galdikas wrote in “Reflections of Eden”: At first I simply could not understand how a large, lumbering, two- to three-hundred pound male orangutan covered with bright red hair could virtually melt into the dark shadows of the canopy. I finally deduced that in the shade, the sparse hair of the orangutan almost disappeared from view because no light caught its tips. All one could see was the orange dark skin. Only in the sunlight would the hair catch the light, causing it to blaze as the orangutan were on fire." [Source: “Reflections of Eden” by Biruté Galdikas]

"Hidden high in the crowns of the trees, amid heavy foliage, an orangutan becomes a shapeless black shadow,” Galdikas wrote. “To perfect my spotting technique, I had to learn the search images. I needed to look for shadows that were black and amorphous, and not the shape and color of large, bright orange orangutans."

Orangutan Tree-Dwelling Behavior

Orangutans are mostly active in the day and live mostly in primary rain forests, ranging from those found in swamps to those in mountains as high as 1,500 meters. They need a fair amount space. Males generally need two to six square kilometers each.

Orangutans are generally placid creatures. They sleep in the canopy in large platform nests made from leaves and branches. They usually build a new nest every evening but will sometimes sleep in the same one for more than one night. Some can make a new nest in less than 5 minutes. When it rains orangutans sometimes climb underneath the nest, using it as an umbrella.

Orangutans spend most of their lives eating and resting. They move slowly during the day, covering only 200 to 1,000 meters a day, considerably less than gibbons. They are most active in the morning and the afternoons. Orangutans’ large size makes it much more difficult for them to move through the forest than lighter, more agile monkeys and gibbons. They can not swing through the canopy, where the branches too light and thin to bear their weight, like gibbons. Thus orangutans move around in lower sections of the forest by moving to the end of branches until their weight drops them to where they can grasp onto another branch.

Orangutans generally dislike water. Some orangutans spend as much as half the day on the ground. When they do drop down to the rain forest floor to forage they travel around on all fours foraging at intervals up to six hours. Males have been observed walking through rice fields and napping on the ground and even building nests on the ground. .

Orangutan Anti-Social Behavior

"Large and mostly silent, orangutans are relatively slow, solitary animals. They do not travel in big, noisy groups like chimpanzees, or in large families like gorillas. Spotting one orangutan did not mean the others were nearby. Traveling 100 feet in the dense tropical rain forest canopy, orangutans are masters of hide and seek — now you see them know you don't." [Source: “Reflections of Eden” by Biruté Galdikas]

Orangutans are the least social of the great apes. They are largely solitary and don't seem to care much for the company of their own sex or members of the opposite sex. Adult males and females only come together when they have to mate. Males are nearly always seen alone and go out of their way to avoid each other. Their only contact it seems is vigorously defending their territories against other males. The Dyak believe that human loners belong to the tribe of the orangutans and gregarious people are kin to of gibbons.

Orangutans rarely groom each other like many other primates do. Male-to-male combat, females sneaking way from males they didn't want to mate with are characteristic behavior when they do come in contact with one another. The only real bonding is between a mother and her offspring. Occasionally females with assorted offspring are seen traveling and foraging together but this is rare. Sub adult orangutans are more likely to be seen the company of other orangutans than older ones. They travel alone or with their mothers and sometimes play with other sub adults of both sexes.

Orangutans are the only diurnal primates that exhibit such anti-social behavior. Galdikas believes the solitary nature of orangutans makes sense in their rain forest habitat. If a group of orangutans invaded a fruiting tree they would strip the tree of every ripe piece of fruit and none of the apes would be satisfied. Alone they get enough to satiated their huge appetites.

Orangutan Dreams, Aggression and Self Awareness

Orangutans and chimpanzees are the only two animals that pass the mark test, a measurement of being self aware. In this test an animal is anaesthetized and marked with an odorless dye above an eyebrow or ear. The animal passes if it touches the mark after being shown a mirror after it wakes up. Apes can recognize themselves in a mirror while monkeys think they are confronted with another monkey.

Apes may dream; they have rapid eye movement. One naturalist described a young orangutan who woke up screaming as if they had just had a nightmare. The orangutan t turns out had witnessed his mother being shot down from a tree by tribesman and killed, skinned and eaten before his eyes. Orangutans are also quick learners but sometimes at the cost of unanticipated cost. An orangutan couple in Russia followed instructions from a video on good patenting and then became addicted to television and neglected each other.

Bill Brubaker wrote in Smithsonian magazine, Males are frighteningly unpredictable. Galdikas recalls one who picked up her front porch bench and hurled it like a missile. "It's not that they're malicious," Galdikas assures me, gesturing toward the old bench. "It's just that their testosterone surge will explode and they can be very dangerous, inadvertently." She adds, perhaps as a warning that I shouldn't get too chummy with Tom and Kusasi, "if that bench had hit somebody on the head, that person would have been maimed for life." [Source: Bill Brubaker, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010]

When I visited Gunung Leuser National Park in Sumatra my guide told me several stories about aggressive orangutans. The guide said once a large male started chasing him down a trail and rolled itself into a ball and somersaulted down a downhill section of trail to catch up to the guide, who said he was vigorously man-handled by the ape but emerged more or less uninjured.

Orangutans Customs and Culture

Orangutans pass on behavior from one generation to the next. Some of these “customs” are unique to particular groups which some scientist argue is an expression of “culture,” which is defined as the ability to invent new behaviors adopted by a group which are then passed down to succeeding generations. It was previously thought that only humans and chimpanzees possessed “culture.”

There are a number of examples of orangutans living in one area that possess culture and customs that other groups don’t have. One group at Gunung Palung National Park in Borneo, for example, threatens strangers by making kiss-squeaking noise into a handful of leaves. In Sumatra, orangutans use sticks to pry nutritious seeds from prickly, difficult-to-eat “Neesia” fruits. Others make a raspberry-like noise before turning in for the night, use their fists to amplify sound, employ leaves as gloves when handling spiny fruits, dip leaves in a hole with water and lick the leaves, use leaves as napkins and employ sticks to poke out sections of termite nests.

What is remarkable about the finding compared to other apes is that orangutans are much less social than chimpanzees and humans. Galdikas wrote in Science, “If orangutans have culture, then its tells us that the capacity to develop culture is very ancient...orangutans separated from our ancestors and from the African apes many millions of years ago.” The study suggests “they may have had culture before they separated.”

Feeding Orangutans

Orangutans mostly eat fruit and have a strong preference for wild figs and will travel long distances to seek out fig trees when they are fruiting. They will also eat young leaves and soft material on the inside of tree bark, fungus, wild ginger roots, durians, the red fruit from “baccaurea” trees, “pandanus”, most forms of vegetation, grubs, ants and termites and dirt. Altogether they have been observed eating 400 different items found in the tropical rain forest, including fruit, flowers, bark, leaves and insects.

Wild orangutans are rarely seen eating meat (one scientist saw an orangutan eating a gibbon carcass) although they been observed eating insects, termites, rats and bird's eggs. Sometimes the seem inappropriate more by curiosity than hunger and desire. In zoos, they readily accept meat.

Many orangutans are at the mercy of boom and bust cycles of rain forest fruit. They gorge themselves silly on high-calorie fruit when there is a mast fruiting (when a large number of trees bear fruit at the same time). When times are lean the eat food that are plentiful but low in calories such as leaves bark and stems. Travel patterns of orangutans are affected by the cycle: namely they have to move around more when food sources are more limited. The cycle is also believed to have an affect on when males mature and when females decide to have children.

Rather than eating a whole fruit, orangutans often take a bite form the juiciest part and then throw the rest fruit. One of their favorite treats is the “banitan” fruit which contains two large pits that are so hard even a nutcracker won't break them. To get at the coconut-like material inside orangutans spend hours crushing the pits with their teeth. Orangutans have also been observed hang upside down from branches to drink from a river and bending fruit tree branches to reach them.

Bill Brubaker wrote in Smithsonian magazine, “Males usually search for food alone, while females bring along one or two of their offspring. Orangs have a keen sense of where the good stuff can be found. "I was in the forest once, following a wild orangutan female, and I knew we were about two kilometers from a durian tree that was fruiting," Galdikas says on the front porch of her bungalow at Camp Leakey. "Right there, I was able to predict that she was heading for that tree. And she traveled in a straight line, not meandering at all until she reached the tree." [Source: Bill Brubaker, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010]

Orangutan Noises and Gestures

Orangutans are generally quieter than other higher primates. Scientist have recorded 15 orangutan vocalizations, the most notable of which is the “long call,” is a hair-raising, minutes-long, sequence of roars and groans by the male that can carry a mile and are used to define his territory and space himself from other orangutans. Male mating calls are rarely heard.

Bill Brubaker wrote in Smithsonian magazine, Galdikas “has made discoveries about how males communicate with one another. While it was known that they use their throat pouches to make bellowing "long calls," signaling their presence to females and asserting their dominance (real or imagined) to other males, she discerned a call reserved especially for fellow males; roughly translated, this "fast call" says: I know you're out there and I'm ready to fight you. [Source: Bill Brubaker, Smithsonian magazine, December 2010]

Orangutans loudly smack their lips and throw branches when they sense an invader. When they see a friend they suck their lips in and get a goofy look on their face. Orangutans in both Borneo and Sumatra use leaves to make loud noises. Different groups also make “kiss-squeak” and sputtery raspberry noises. Once when an orangutan was accused of murdering an infant orangutan it raised its hands above its head and then drooped them down fluttering in front of him as if is to say "I give up you win."

Orangutan Males and Females

Males roam the forest alone, consuming huge amounts of fruit. Fully developed males are known as prime males. When they are at their peak they have full cheek pads, large throat pouches and make loud bellowing noises that carry over long distances to announce their presence.

Prime males are only in top physical condition for a few years. Chasing after females and fighting other males takes its toll. Their cheek pads and throat pouches shrink and their ability to make loud calls diminishes. When this occurs their reproductive life cycle ends.

Males sometimes get into vicious fights during the mating season. These fights can be deadly. Males have been seen with severe wounds and canine marks all over their body from fights with other males. In some cases injuries are so bad they prevent the orangutans from moving through the forest and eating, leading to the animal’s likely death. In most cases when two males meet, the dominate one is clear and a fight is avoided when the subordinate one backs off. Females are less hostile to one another that males. Occasionally pairs of females hang out and travel together for up to three days.

Describing a fight between males, Galdikas wrote, “They grappled furiously, biting one another; they fell repeatedly and chased each other into the trees again to resume the fight. Their backs glistened with sweat, its pungent odor lingering on the ground long after they were back in the trees. A few times they pulled apart and stared intently at each other. Then after more than 20 minutes, they separated and sat on adjacent trees. With a mighty heave T.P. threw a snag — and roared. The other male disappeared.”

Cheryl Knott, an anthropologist at Borneo’s Gunung Paiung National Park, Indonesia, wrote in National Geographic: A “significant find at our site was that fully developed adult male orangutans, known as prime males, stay in top physical condition only for a few years. Prime male Jari Manls was in top condition in April 1997 when National Geographic first took his photo (the August 1998 issue). But 19 months later he was a shadow of his former self. Shriveled cheek pads illustrate the difficulty of maintaining peak condition. Martina was likely fathered by Jarí during his prime. Following females and fighting with other males wears them down, diminishing masculine traits such as full cheek pads and large throat pouches and curbing certain behaviors like mating and long-calling — a loud bellowing made to announce their presence. As these features disappear, males become what I call past prime, a condition that usually signals the end of their reproductive cycles. [Source: Cheryl Knott, National Geographic, October 2003]

“Many orangutan males delay developing prime traits for several years, although they’re still capable of fathering offspring. I believe the environment may be partly responsible, Natural plant cycles cause severe fluctuations in fruit production. During shortages orangutans consumer fewer calories — and in females this translates to lower fertility. In response males may wait to attain their prime condition until future time when food is more abundant and they have the best chance of reproducing.”

Orangutan Reproduction

Orangutans have a slow rate of reproduction. Females only give birth up to once every eight years — thought to be longest span of any mammal — even though they ovulate and are capable of getting pregnant once a month. They breed so slowly because the female devotes here attention to rasing her young, which develop slowly, requiring years of maternal care and training. Females spend up to 10 years raising a single offspring, during which time they don't mate.

Both males and females reach sexual maturity at around seven or eight years of age. However, females do not usually give birth until they are about 12 and males do not reach their full sexual maturity until they are around 14. Females sometimes only conceive during periods of high fruit production.

Females prefer larger older males, who in turn are successful beating off male rivals. Galdikas observed one young female abandon a young male “friend” to have sex with older male. The young male seemed jealous and depressed and slunk around in the trees nearby but did not challenge the older male. Sexual competition helps explain why males are so much larger than females. Males need to be strong to fight one another, females do not and if anything a large size makes it more difficult to maneuver around the trees.

Orangutan Sex

The females usually do the choosing and they can be quite bold, displaying their genitals, swinging around in a showy manner and even wacking an uninterested male on the head with a piece of fruit or a branch. When a female orangutan gets the urge she will tweak the penis of the nearest male which males seems to find more embarrassing than arousing..

Females are not ready to mate often but when they are males come from all over. Sometimes clumsy or inexperienced males cause the females to scream in pain or irritation. Females are sometimes raped by large males.

Orangutans sometimes have sex in the face to face position. They are one of the few animal species other than humans that do this. There are even examples of platonic love in the orangutan world. One male liked to have sex with unwilling females but at his side almost all the time was another female he never had sex with.

On his encounter with a lusty male orangutan, John Gittelsohn of Bloomberg wrote: “The sign at Camp Leakey on the Indonesian island of Borneo says: “Never stand between a male and a female orangutan.” We were watching a group of female orangutans feasting on bananas, babies clinging to their bellies, when we learned why. First came the sound of snapping branches, like a bulldozer crashing through the forest. The mother orangutans stuffed their mouths with bananas and started to flee just as Tom, a massive red-haired ape with black cheek pads framing his glassy brown eyes, swung down from the trees. One female, Akmad, was too slow to escape the long arm of Tom. He grabbed her ankle, tossed her on her back and had his way in less than a minute. When Tom was finished, he let out a loud fart. [Source: John Gittelsohn, Bloomberg, June 3, 2012]

Young Orangutans

Females usually give birth to one infant at a time The gestation period averages 245 days.The mean birth weight is about 1½ kilograms. Baby orangutans remain close to their mothers. They like to stare at their mother's face. The single infant remains with its mother for eight or nine years.

Young orangutans cling to their mothers for the first one year or so of their lives and often continue to ride on their mothers until they are 2½. Often mothers will hurl themselves through the canopy at great speed with their young holding on tight to handfuls of skin and hair. A one-year-old youngster adopted Galdikas as his mother. He cling to her night and day. So unyielding was his affection Galdikas couldn't take a bath without him whining to grab hold of her. Changing her clothes was next to impossible.

Chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutan mothers dote on their young. Mothers raise their young in fairly settled surroundings, nursing them for six years, never leaving them, and not weaning them until they are pregnant with another baby. After they have been weaned young orangutans usually establish a territory near their mother’s territory. Only when they are seven or eight do they go off and establish a territory of their own.

"Young orangutans are utterly charming — wide-eyed, playful and trusting." They are often sought as pets. Young orangutans learn the skills necessary to survive in the forest from their mothers. Young protest loudly of their mother won’t share food with them. Those who lose their mothers are often unable to take care of themselves. When the mother deems it is time for young to move on she can be quite rough in persistent in throwing the young out of her nest.

Tool-Using Orangutans

Orangutans have been observed using sticks to pry nutritious seeds from prickly, difficult-to-eat “Neesia” fruits; using their fists to amplify sound; dipping leaves into holes with water and licking the leaves; using leaves as napkins; and employing sticks to poke out sections of termite nests. Orangutans sometimes use leaves like a glove to climb up trees with a horny bark, which they strip away to get the delicious sap underneath.

Orangutans have also been observed using leaves as cups to pick up water from a stream and raising it to their pursed lips. They use a similar method to extract honey from bee nests inside the holes of trees. David Attenborough wrote: “To collect ants or termites, they break off twigs, sometimes chewing the end to form a kind of brush. Then they use these tools to chip away at a nest. Young orangs who stay with their mothers for three or four years doubtless learn these techniques from her.”

On how an orangutan gets seeds from Nessia fruit, Attenborough wrote: “The Nessia tree does not rely on animals to distribute its seeds. The job is done by the waters that regulalrly flood into the forest. The seeds, accordingly, are not wrapped in sweet flesh to tempt animals to swallow the, but protected from those that might make a meal of them by a hard husk covered by stinging hairs. In most parts of Sumatra, orangs ignore Neesia fruit. But not in the northern forests. Here the orangs have discovered how to open hem. The technique is quite complicated. First the stinging hais that cover the husk have to be removed. To do that, an orang produces a special tool. A twig cleaned of its bark . Holding this in his teeth, it carefully cleans off the unpoleasant hairs. Then it opens the fruit by ramming a piece of wood into a crack and forcing the husk apart until it is possible to hook out the seeds with a finger. Doubtless it was one particularly innovative individual that devised the technique many years ago. But because here, thanks to the abundant food supply, adults sometimes feed together, the skill spread by imitation and these northern orangs have a culture that differs from that of any other group. So the comparative simplicity or orangutan behavior elsewhere may be connected to eh fact that the scarcity of food prevents them from living in groups.”

Tool use by wild orangutans is more limited than that reported for chimpanzees. Some scientists think is probably due more to the solitary nature of orangutans rather than a lack of intelligence. But those who have had contact with humans have show quite sophisticated to usage. Galdikas and Brindamour witnessed only two example of tools use that didn't seem to be acts of imitation. One orangutan on his first day of freedom tried to open a coconut with a stick. Another used a branch as a back scratcher. There is evidence that orangutans know how to use plants for medicinal purposes.

Orangutan Murder and Deceit

As is true with chimpanzees it was discovered that orangutans are capable of murder. One seven year-old drowned and mutilated two infant orangutan in a river and was caught trying to do the same to a young female. What was surprising about the murderer is that it had spent more time around humans than any of the others at the Tanjung Puting rehabilitation center. There have also been reports of orangutan kidnaping. A female who was not lactating broke into a rehabilitation center in Sumatra and carried of an infant into the forest.

The New York Times reported: “Great apes, for example, make great fakers. Frans B. M. de Waal, a professor at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center and Emory University, said chimpanzees or orangutans in captivity sometimes tried to lure human strangers over to their enclosure by holding out a piece of straw while putting on their friendliest face. “People think, Oh, he likes me, and they approach,” Dr. de Waal said. “And before you know it, the ape has grabbed their ankle and is closing in for the bite. It’s a very dangerous situation.” Apes wouldn’t try this on their own kind. “They know each other too well to get away with it,” Dr. de Waal said. “Holding out a straw with a sweet face is such a cheap trick, only a naïve human would fall for it.” [Source: Natalie Angier, New York Times, December 22, 2008]

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, Natural History magazine, Smithsonian magazine, Wikipedia, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Top Secret Animal Attack Files website, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, The Economist, BBC, and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2012