HMONG SOCIETY

Hmong in Vietnam

For the Hmong patrilineal descent defines kin groups which in turn form the basis of village and community organization. Most villages are made up of members of local lineages that can trace their origin back to a common ancestor. Status and rank are determined by age and lineage. Major lineage differences are distinguished by variations in household rituals and funeral ceremonies. The ritual head of the lineage is the oldest living member of that lineage.

Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino wrote in the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: “The household and the clan are the key units of Hmong life. Primary loyalty is to them, not to a village or region. Hmong like to live near their clan relatives, whom they can call on for social, economic, and emotional support. Ethnic prejudice against the Hmong complicates their relations with lowland people. [Source: Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

A Hmong's last name is a clan name. About 18 clans have been identified in Thailand and Laos. These patrilineal exogamous clans each trace their descent back to a common mythical ancestor. There are several subdivisions in Hmong society, usually named according to features of traditional dress. The White Hmong, Striped Hmong, and Green Hmong (sometimes called Blue Hmong) are the most numerous. Their languages are somewhat different but mutually comprehensible, and all recognize the same clans. Each village usually has at least two clans represented, although one may be more numerous. Wives almost always live with their husband's family. [Source: Library of Congress]

Villages are relatively self sufficient. Villagers grow their own food. Their political and social units are the family, clan and the village. Hmong villages are relatively egalitarian. Inheritance is not a big thing because there is little privately owned land and thus little land to inherit. Property is generally divvied out at marriage and when houses are built and children are born rather than at death.

The Hmong language and culture is nuanced and subtle. Hmong that have come to the United States find Americans uncomfortably blunt and direct. Most disputes are between local lineages over marriages, bride-price payments, children born out wedlock and extramarital affairs. There are also been disputed over Christian proselytizing and land claims. In rare cases lineages declare war on one another. Problems and disputes are arbitrated on the village level by an assembly of male lineage elders. At assemblies women can play an informal role. The ritual head of the lineage and the village shaman have the highest status. In some places village headmen are appointed to deal with specific issues such as extramarital affairs. Social control is exerted more through traditional customs and taboos that laws of the nation, where the Hmong live. Gossip, accusations f witchcraft and the power of men over women and fathers over sons are also used to exert social control.

See Separate Articles HMONG MINORITY: HISTORY, RELIGION AND GROUPS factsanddetails.com; HMONG IN AMERICA factsanddetails.com; HMONG, THE VIETNAM WAR, LAOS AND THAILAND factsanddetails.comMIAO MINORITY: HISTORY, GROUPS, RELIGION factsanddetails.com; MIAO MINORITY: SOCIETY, LIFE, MARRIAGE AND FARMING factsanddetails.com ; MIAO CULTURE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: "Culture and Customs of the Hmong" by Gary Yia Lee and Nicholas Tapp Amazon.com; "An Introduction to Hmong Culture Illustrated Edition" by Ya Po Cha Amazon.com; “Hmong Language: The Hmong Phrasebook” by Blong Kong Amazon.com; “A People's History of the Hmong” by Paul Hillmer Amazon.com; “Calling in the Soul: Gender and the Cycle of Life in a Hmong Village” by Patricia V. Symonds Amazon.com; “Folk Stories of the Hmong: Peoples of Laos, Thailand, and Vietnam” by Dia Cha and Norma J. Livo Amazon.com; Miao: “Hmong/Miao in Asia” by Nicholas Tapp, Jean Michaud, et al. Amazon.com; “Butterfly Mother: Miao (Hmong) Creation Epics from Guizhou” by Mark Bender Amazon.com; “The Art of Ethnography: A Chinese "Miao Album"” by David Deal, Laura Hostetler, et al. Amazon.com ; “Minority Rules: The Miao and the Feminine in China's Cultural Politics” by Louisa Schein Amazon.com; “Tourism and Prosperity in Miao Land: Power and Inequality in Rural Ethnic China’ by Xianghong Feng Amazon.com; Textiles, Clothes, Jewelry: “Miao's Attires” by Wan Zhixian, Yan Da, et al. Amazon.com; “Ethnic Miao Silver” by Yu Weiren and Wan Zhixian Amazon.com; “Every Thread a Story & The Secret Language of Miao Embroidery” by Karen Elting Brock, Wang Jun, et al. Amazon.com; “Miao Textiles from China” by Gina Corrigan Amazon.com; “Children Of The Meo Hill Tribes” (1981) by Campbell Bruce Hawker Frances Amazon.com

Hmong Life

Rice, the staple of the Hmong diet, is supplemented with bread made from corn. The Hmong like to eat pumpkin vines stir fried with fish sauce, lemon grass and chilies. Pumpkin fruit is given to pigs to eat. Corn is also distilled in a powerful moonshine. Less potent rice wine, known as room, is consumed from a communal crock with four-foot-long straws. According to journalist Howard Sochurek room tastes like white wine that has turned to vinegar. Hmong drink bitter green tea out of fine china cups and eat stir fried dishes prepared in a wok.Women often smokes pipes packed with marijuana when they do their work.

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: “The Hmong prefer white rice to sticky rice, but grow both kinds. Sometimes they have to buy additional rice. Other food comes from their fields and gardens, supplemented by hunting, fishing, and gathering. Corn is always grown along with squash, melons, and greens of various kinds. Tubers, shoots, mushrooms, and other wild plants are found in the forest. Various rodents and insects are also eaten. Most foods are boiled and seasoned with salt and chilies. Meat is rarely part of the diet, although occasionally a hunter gets lucky. The pigs and cattle they raise are largely for sacrifices to the spirits, but they are eaten on ceremonial occasions once the offering has been made. There are usually bananas and other fruit trees and often some sugar cane. Wild foods and fish are abundant during the rainy season, but little grows in the hot dry season. [Source: Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

“In Laos, living conditions for Hmong are rather poor. Village houses cluster together on barren mountain tops. The house is set directly on the ground with a beaten earth floor. The walls are usually made of split bamboo and the roof of thatch. Usually 6–8 people live in a house measuring 6 x 8 m. Furnishings are minimal—a couple of stools and a table. A sleeping alcove is set a foot or two above the floor. There may be a walled-off bedroom for a couple. Much of the house may be used for storage, with a granary, tools, etc. An open hearth is used for cooking. The pigs and chickens may be brought into the house at night but wander freely in the daytime. There is usually no electricity, no running water, and no sanitary facilities. The pigs keep the village clear of edible refuse and human waste. Access to health care is limited. Travel is usually by foot, although wealthier families may have pack horses. There are few roads. Each family tries to be as self-sufficient as possible. Despite these conditions, Hmong villages are often more prosperous than those of surrounding minorities. This is due in part to remittances from overseas Hmong. In some cases, the income discrepancies between Hmong and their poorer ethnic neighbors creates tension, particularly when Hmong are able to buy the ancestral lands of other groups. *\

“Schools have been extended to Hmong areas only in recent years in Thailand and Laos. Many Hmong settlements are still remote from schools. Most Hmong in Laos attend school only for a year or two. Males are more likely to attend school and study longer than females. Most Hmong men can speak the national language to some extent and may have gained some literacy in it. Females are more likely to be illiterate. Education occasionally is an issue in Hmong families in the United States. Sometimes traditional parents want their teenage daughters to leave school and enter an arranged marriage, while their more Americanized daughters rebel. *\

“As governments have extended their control of border regions, the Hmong are under great pressure to give up their traditional way of life and settle down. Settled agriculture, wage labor, and the cash economy are replacing traditional self-sufficiency and have led to more emphasis on the individual and less on clan ties. Children exposed to lowland life are assimilating the dominant culture. Generational contrast and conflict is particularly acute for refugee families living in modern cities in the United States. It is a challenge to maintain Hmong culture and language while adapting to modern life. *\

Hmong Marriages

Hmong wedding

Arranged marriages are the norm but couples are often given a degree of freedom in choosing a partner. Marriages outside the clothing color, language or dialect group are uncommon. When a women marries she leaves her family and clan and enters the family and clan of her husband. She often moves to her husband’s village When she dies she is worshiped by his descendants. Usually only the youngest son lives with the parents after marriage.

Couples have traditionally been monogamous, but polygamy is practiced. For a while it was encouraged because so many men were killed during the Vietnam War and it was difficult to find husbands for all the women. In polygamous unions two or three wives often live in the same house. Because bride prices are so high generally only rich could afford to have multiple wives.

The Hmong practice polygyny, although the government officially discourages the custom. Given the regular need for labor in the swidden fields, an additional wife and children can improve the fortunes of a family by changing the consumer/worker balance in the household and facilitating expansion of cropped areas, particularly the labor-intensive opium crop. Yet the need to pay bride-price limits the numbers of men who can afford a second (or third) wife. *

Anthropological reports for Hmong in Thailand and Laos in the 1970s suggested that between 20 and 30 percent of marriages were polygynous. However, more recent studies since the mid-1980s indicate a lower rate not exceeding 10 percent of all households. Divorce is possible but discouraged. In the case of marital conflict, elders of the two clans attempt to reconcile the husband and wife, and a hearing is convened before the village headman. If reconciliation is not possible, the wife may return to her family. Disposition of the bride-price and custody of the children depend largely on the circumstances of the divorce and which party initiates the separation. *

After a young married man dies, according to Hmong tradition, his widow is married to clan member, who provides for her children.The Hmong also practice levirate marriages. If a man dies his eldest brother usually has first dibs on the widow. If he doesn't want her, the widow's family is required to return some of the bride-price. Bride kidnapping is still practiced by the Hmong. In many cases it is nothing but elopement and usually occurs when parents disapprove of a match or boy doesn't get along with the girls parents.

Couples are often very young when they get married. Many get married when they 14 or 15. Divorces are uncommon, partly because the bride prices are so high that the bride’s family is unwilling to return it. Often the only way an unhappy wife can get out of here marriage is through suicide.

Hmong Courting

Young people are permitted to enjoy a "golden period of life" in which premarital sex is allowed and even encouraged. Many villages have traditionally had “youth houses,” where unmarried young people could meet. In some cases groups of young men travel from village to village to met up with young women at these houses. Marriage often takes place at the first pregnancy.

According to “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”: “Young men and women mix freely, and premarital sex is accepted as the norm, much to the horror of the dominant populations where they reside; women are expected to be chaste even if the men are promiscuous. Pregnancy usually leads to marriage. [Source: Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ++]

Prospective couples often begin their relationship by playing a courtship game called pov pob, dancing and singing antiphonal songs during the Hmong New Year festival (See Hmong New Year festival). If a couple decides to marry the family of the groom has to give the bride's family a bride price in silver and animals that usually amounts to several thousand dollars, quite a lot of a Hmong family. Unions are often sealed with a pig. In lieu of a bride price or sometimes in addition to one the husband works for two years for the bride’s parents to make up for the loss of their daughter, who is regarded as a strong, hard worker.

See Sapa Love Market Under SAPA: HILL TRIBES, TREKKING, KARST SCENERY AND THE LOVE MARKET factsanddetails.com

New Year courting game in Laos

Hmong Weddings

Marriage is traditionally arranged by go-betweens who represent the boy's family to the girl's parents. If the union is acceptable, a bride-price is negotiated, typically ranging from three to ten silver bars, worth about US$100 each, a partial artifact from the opium trade. The wedding takes place in two installments, first at the bride's house, followed by a procession to the groom's house where a second ceremony occurs. Sometimes the young man arranges with his friends to "steal" a bride; the young men persuade the girl to come out of her house late at night and abduct her to the house of her suitor. Confronted by the fait accompli, the girl's parents usually accept a considerably lower bride-price than might otherwise be demanded. Although some bride stealing undoubtedly involves actual abductions, it more frequently occurs with the connivance of the girl and is a form of elopement. [Source: Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Before a Hmong marriage a chicken is sometimes killed in front of the husband and bride to be. If the chicken's eyes are identical that means the marriage will be a happy one. If the eyes are different that is a bad omen, and the wedding plans are quickly scrapped. The weight the chicken is also significant. If either the bride or the groom breaks the engagement their family has to pay the other family the weight of the chicken in silver.

As a result of a government directive discouraging excessive expenditures on weddings, some districts with substantial Hmong populations decided in the early 1980s to abolish the institution of bride-price, which had already been administratively limited by the government to between one and three silver bars. In addition, most marriages reportedly occurred by "wife stealing" or elopement, rather than by arrangement. In the past, males had to wait for marriage until they had saved an adequate sum for the bride-price, occasionally until their mid-twenties; with its abolition, they seemed to be marrying earlier. Hmong women typically marry between fourteen and eighteen years of age. *

Hmong Women and Men

Hmong gender roles are strongly differentiated. Women are responsible for all household chores, including cooking, grinding corn, husking rice, and child care, in addition to regular farming tasks. Patrilocal residence and strong deference expected toward men and elders of either sex often make the role of daughter-in-law a difficult one. Under the direction of her mother-in-law, the young bride is commonly expected to carry out many of the general household tasks. This subordinate role may be a source of considerable hardship and tension. Farm tasks are the responsibility of both men and women, with some specialization by gender. Only men fell trees in the swidden clearing operation, although both sexes clear the grass and smaller brush; only men are involved in the burning operation. [Source: Library of Congress]

During planting, men punch the holes followed by the women who place and cover the seeds. Both men and women are involved in the weeding process, but it appears that women do more of this task, as well as carry more than half of the harvested grain from the fields to the village. Harvesting and threshing are shared. Women primarily care for such small animals as chickens and pigs, while men are in charge of buffalo, oxen, and horses. Except for the rare household with some paddy fields, the buffalo are not trained but simply turned out to forage most of the year.

Hmong women have traditionally done the most work: cleaning, cooking, pounding rice, tilling the fields, taking care of the children and making clothes. Men have traditionally woven baskets, plowed the fields, hunted for meat and defended the village from enemies. But, in many cases, the traditional work system has broken down and women do all the work. Many Hmong men don't do much except sit around the village and get drunk or smoke opium. Women sometimes say they are so busy they encourage their husband to take another wife so they don't have so much work to do.

Hmong women are famous for their embroidery and cloth making skills. They spend a lot of their time spinning, weaving and embroidering cloth often made from hemp, ramie and cotton they grow themselves. Often a woman's ability to attract a good husband is determined by how well she can sew. Because Hmong women don't use sewing machines, pins or patterns their stitches are virtually invisible. Some Hmong women in America have had success cashing in on their sewing skills.

Hmong Families and Children

Hmong households traditionally consist of large patrilineal extended families, with the parents, children, and wives and children of married sons all living under the same roof. Households of over twenty persons are not uncommon, although ten to twelve persons are more likely. Older sons, however, may establish separate households with their wives and children after achieving economic independence. By the 1990s, a tendency had developed in Laos for households to be smaller and for each son and his wife to establish a separate household when the next son married. Thus, the household tends toward a stem family pattern consisting of parents and unmarried children, plus perhaps one married son. Following this pattern, the youngest son and his wife frequently inherit the parental house; gifts of silver and cattle are made to the other sons at marriage or when they establish a separate residence. In many cases, the new house is physically quite close to the parents' house. [Source: Library of Congress, 1994 *]

Today there are nuclear family and extended family households. A typical Hmong household consists of parents, unmarried children, and married sons and their families. The largest families are made up of parents with young married sons, their wives and children. Fathers have traditionally taken an active role in some aspects of child rearing.

From a young age, children help with chores and become engaged in village life. Literacy rates are low because most children don’t go to school. Young boys are taught to hunt and learn local custom by attending ceremonies and rituals. Girls are taught weaving, singing and other skills from their mothers. Children learn subsistence skills by working in the fields at a relatively young age.

Hmong Villages

making a house, look who's doing the work

The Hmong have traditionally lived in villages located at 3,000 to 6,000 feet, an altitude perfect for growing opium poppies, their major cash crop. Most Hmong have settled in the mountains because the lowlands have always had dense populations and they didn't want to encroach and stir up trouble. In addition the mountain tops are easier to defend and the Hmong seem to prefer a cool climate. Hmong villages are often interspersed with villages of other groups, particularly the Yao, Akha, Ding, Zhuang and Yi.

The Hmong used to say that the world reached only as far as a man could walk. Hmong villages typically have seven to 50 households and are often organized in a horseshoe pattern just below the ridge of a mountain, sheltered by forests and near a water source. The buildings are oriented in accordance with the principals of feng shui. Water is often piped in a series of troughs made from split bamboo or collected from a well or tap system.

Usually bamboo, peach and banana trees are grow around the village to provide food and shade. Many villages have a grove of trees where religious ceremonies are held. Nearby slopes are used to raise herbs and vegetables. Rice and other grains are stored granaries raised off the ground for protection against animals. Chicken coops and stables are also built. Pigs are generally allowed to run free. Some villages have shops run by Chinese traders.

Hmong Homes

Unlike lowlanders, who build their homes on stilts, Hmong houses are built firmly on the ground. Extended families live in the same houses, with each belonging to clan, which is headed by a clan leader. Almost every house has a simple altar mounted on one wall for offerings and ceremonies associated with ancestral spirits. [Source: Library of Congress]

Hmong houses are constructed with walls of vertical wooden planks and a gabled roof of thatch or split bamboo. In size they range from about five by seven meters up to ten by fifteen meters for a large extended household. The interior is divided into a kitchen/cooking alcove at one end and several sleeping alcoves at the other, with beds or sleeping benches raised thirty to forty centimeters above the dirt floor. Rice and unhusked corn are usually stored in large woven bamboo baskets inside the house, although a particularly prosperous household may build a separate granary. Furnishings are minimal: several low stools of wood or bamboo, a low table for eating, and kitchen equipment, which includes a large clay stove over which a large wok is placed for cooking ground corn, food scraps, and forest greens for the pigs.

The traditional Hmong house is built on the ground rather than on piles and has a roof thatched with teak leaves or cognon grass, a dirt floor and no windows. The frame is made of lengths of timber notched together or bound with hemp rope, without the use of nails. In some parts of China Hmong houses are made from mud bricks or stone. In Thailand and Laos they are often built in the Thai style. Families that can afford it have zinc or polyurethane roofs. The poorest of the poor build their houses entirely from split bamboo and matting.

Hmong: sleep on straw sleeping pallets, bamboo beds or wooden platforms and food is cooked over an open fire pit or primitive stove. Every house is built so that the owner can see a distant mountain from the front door. When a site for a house is chosen one grain of rice is laid down for each member of the family and left over night. If the spirits move them a new site must be chosen. [Source: W.E. Garret, National Geographic, January 1974]

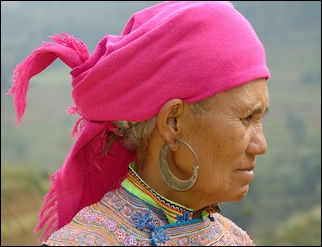

Hmong Clothes, Beauty and Jewelry

Hmong are famous for their traditional costumes and wonderful embroidery. Women wear black tunics and pleated skirts, or calf-length black trousers with a short black skirts, or maroon or colored jacket or shirt with a colorful vest along with silver ornaments, and a turban-like headdresses strung with dangling coins. They sometimes sport silver rings around their necks. They also wear distinctive colorfully-embroidered aprons which Hmong women believe can be dipped in water and used as a wash cloth to cure their husbands of any illness. Many wear gaiter that reach from the knees to the ankles. In Laos women dress in an ornately embroidered skirt, black blouse and tightly wound black turban. Around their waist they wear a silver chain strung with dozens of antique French coins that ring and jangle when they walk.

Hmong men have traditionally worn black short-sleeve tunics, with beautiful embroidered panels on the chest, and black baggy trousers with a crotch so deep it almost touches the ground. Draped around their shoulders and waist are sashes and bandolier-like belt hung with silver coins. On their head they wear turbans, satin skullcaps with pink pompons, or caps that look like crosses between a fez and a yamuka. "Black" Hmong men wear dark skull caps, indigo homespun tunics, with embroidered colors, over long shirts and wide pants, held together by a wide, embroidered belts. Sometimes they have silver loops around their neck, bronze bracelets and a dagger in their belt. [Source: Spencer Sherman, National Geographic, October 1988]

According to the “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life”:Hmong are identified by their clothing, which indicates dialect and regional group. The Green Hmong, the White Hmong, and the smaller group of Striped Hmong are known by the traditional dress of their women. Women of the Green Hmong, sometimes called Blue Hmong, wear short, blue, indigo-dyed skirts, each done in intricate batik patterns and containing hundreds of tiny pleats. The skirts usually have cross-stitch embroidery and appliqué as well. The skirt is worn with a black long-sleeved blouse, leggings, and a black apron. An outfit takes about one year to make in one's spare time. Women also wear large silver neck rings. The men wear short, baggy black pants and black shirts, sometimes with embroidery, a long sash around the waist, and a Chinese-style black cap decorated with embroidery. The White Hmong women wear black pants or white pleated skirts and a black blouse with an elaborately decorated collar piece at the back of the neck. Accessories include embroidered sashes, coin belts, and aprons. The men's pants are not as short and baggy as the Green Hmong outfit. The Striped Hmong women wear blouses with striped sleeves. Women's headdresses may be very elaborate and indicate regional differences. Younger people are more likely to dress like the majority population, in T-shirts and sarongs or pants. [Source: Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 ]

Hmong often wear complex necklaces, bracelets, earnings and headdresses Women wear their hair in topnot surrounded by a towel. In the old days both men and women had gapping holes in their ear lobes. Men used to put ivory stoppers in their holes and women put in wooden disks in theirs. The Hmong don’t have a lot of body hair. Hmong children are amazed by the hair growing on white people's arms. Sometimes they'll try to yank some off as a souvenir. The Hmong used to consider a full set of teeth to be ugly. In the old days each village had a "dentist" who charged one chicken for every four teeth he treated. During the treatment the teeth were chipped and filled into sharp points and then covered with shiny black lacquer made from tree sap. Umbrellas were once considered prized possessions among Hmong women, who used them primarily for protection from the sun. The Hmong equate fair skin with status. The dark-skinned Lao Theung sub-tribe are looked down upon by other Hmong.

Some Hmong, have really long hair. According to the Guinness Book of Record, Hu Sengla, a Hmong man who lived in northern Thailand, had the world’s longest hair. It reached a length of 5.79 meters. He washed his hair only once a year, mainly to earn money from tourists. His brother, Yi Sengla, had the world’s second longest hair. His was 5 meters long. A younger brother cuts his hair.

See Clothes, Beauty and Silver Ornaments in the article MIAO CULTURE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

Hmong Culture

The Hmong are famous for their traditional story cloths and needlework squares with intricate appliquéd designs. Traditionally the latter were presented by a young couple to their parents and parents-in-law with a blessing. These pieces are placed in the coffin with a person after death. This type of needlework has been incorporated into modern handicraft items made for sale. [Source: Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

The Hmong are famous for their traditional story cloths and needlework squares with intricate appliquéd designs. Traditionally the latter were presented by a young couple to their parents and parents-in-law with a blessing. These pieces are placed in the coffin with a person after death. This type of needlework has been incorporated into modern handicraft items made for sale. [Source: Nicholas Tapp and C. Dalpino “Worldmark Encyclopedia of Cultures and Daily Life,” Cengage Learning, 2009 *]

Embroidery, and the chanting of love songs are particularly esteemed skills There are ritual songs, courting songs, and teaching songs. Songs are passed from one generation to another. Many still contain references to life in China, although the Hmong may have left there generations ago. A skilled singer gains great renown among the Hmong. The playing of the reed pipes, the notes of which are said to express the entirety of Hmong customs, is an art that takes many years to acquire. New dances, song forms, and pictorial arts have appeared in the context of the refugee camps. | Lacking a writing system, the Hmong have passed down their legends and ritual ceremonies orally and in crafts (especially textiles) from one generation to another. They are noted for their sung poetry. The exquisite appliqué and embroidery of their story cloths depicts cenes of daily village life for the Hmong: growing corn, caring for pigs and chickens, hauling rice from the fields, etc. Some have a story line that meanders across the cloth. More recent story cloths tell of war, exile, and going to America. *\

The Hmong are often so busy with chores they have no time for sports or entertainment. Even young children often have to work long hours. Hmong boys like to play with spinning tops. Fishing is often an activity that children do. Hmong sung poetry is a favorite form of entertainment. Often the songs deal with loss—of one's family, one's love, or one's homeland.

Hmong Literature and Music See MIAO CULTURE, MUSIC AND CLOTHES factsanddetails.com

Hmong Health

The Hmong believe that the length of one's life is predetermined, and life prolonging or life saving care is futile. Hmong believe minor illness is organic but serious illness is supernaturally caused. Though immigrants may wish to use a shaman or spiritual healer, they can be expensive. Also, they are not easy to find in the U.S., and since many specialize in different types of disorders, one may not be able to find the right healer for their malady. [Source: Pamela LaBorde, MD, Ethnomed]

For example, the Mien and Hmong believe that there are supernatural factors, more so than biological factors, which contribute to sickness. Consequently, they seek treatment from priests who they believe can communicate with higher beings. Women from these groups often refuse anesthesia when giving birth.

The average Hmong life span in some places in the 1970s was 35; the infant mortality rate was fifty percent. The Hmong have been in the mountains for so long they easily get tropical diseases when they head into the lowlands. Eighty percent of all Hmong get malaria in the lowlands if they don't take medication.

The Hmong, like most hill tribes, believe that physical deformities such as withered arms and club feet are punishments for misdeeds performed by ancestors. The Hmong also believe that surgery maims the body and makes it difficult for a person to be reincarnated. "If a child is born blind," a Hmong man in America told the New York Times, "We don't face it. If we try to change it, someone else in the family will die and get sick."

To ease the pain of a headache, a water buffalo horn is heated by a fire and then suctioned into place at the site of the headache. Massage and magic therapy is also used. Modern medicine is valued where it is available.

Hmong Healing Ceremonies

Sickness, many hill tribes believe, results when evil spirits lure the soul from the body. The Hmong believe that the soul can only be taken through the front door and potential evil-spirit carriers such as pregnant women are supposed to enter through the backdoor. Wrist-tying is a custom performed by almost all the hill tribes do to keep an individual's 32 to 64 souls (depending on the tribe) within its body.

The Hmong rely on shaman and female herbalist to treat sickness. During a ceremony that offers thanks to the gods for healing a sick baby, a Hmong shaman known as tu-ua-neng mix rice and corn mix rice and corn liquor with herbs and folk medicine and offer it to chanting participants. The shaman then goes into frenzied trances to make deals with evil spirits in the clouds, at the bottom of a pond, in China to exorcize evil spirits from a house. Deals with the spirits are usually sealed with a pig or cow sacrifice from a rich customer and chicken sacrifice from poor one. [Source: "The Hmong of Laos" by W.E. Garret, January 1974]

In another kind of healing ceremony a spider is dropped on the sick person's head. The Hmong believe that a spider spirit is the most important spirit to have near one's head. Each night the spider spirit leaves the head when a person sleeps, the Hmong say, and it returns when he or she wakes up. Sickness occurs if the spider's spirit leaves the body when a person is awake. To become healthy again the spider's soul is encouraged to return to the body.

Hmong Economy

Most Hmong have traditionally been and continue to be farmers. The Hmong do not produce their own pottery. Their villages generally do not have any full time craftsmen. As with all Laotian ethnic groups, there is virtually no occupational specialization in Hmong villages. Everyone is first and foremost a subsistence farmer, although some people may have additional specialized skills or social roles. The only jobs are that of blacksmiths, wedding go-betweens, funeral specialists and shaman.

The trading of opium for rice or cash has traditionally been the most important economic activity. Individual households sold opium to traders and representatives of organized paramilitary groups that visited at the time of the harvest. In Laos the Hmong traditionally grew more opium than any other group.

Hmong communities have traditionally not had regional markets and engaged in a batter economy in which iron was the media of exchange. They have traditionally relied on trade with other groups and occasionally visited lowland markets and towns to get supplies and sometimes sell silver jewelry, forest products or vegetables. Some sell silver jewelry and traditional cotton clothes to tourist shops.

Hmong men have traditionally hunted wild game in the forests with flintlock muskets and crossbows and poisoned arrows. During the Vietnam War, tribesman often used grenades for fishing. The exploding grenades, which were tossed underwater, usually didn't kill the fish but stunned them long enough so that they could be gathered up by hand. Entire villages would sometimes assembled around a river to collect the fish before they were swept away by the current. While they collected fish some tribesmen held fish in their mouth to free their hands to catch more fish.

See Economy, Wealth Under MIAO MINORITY: SOCIETY, LIFE, MARRIAGE AND FARMING factsanddetails.com

market in Vietnam

Hmong Agriculture

The Hmong swidden farming system is based on white (nonglutinous) rice, supplemented with corn, several kinds of tubers, and a wide variety of vegetables and squash. Rice is the preferred food, but historical evidence indicates that corn was also a major food crop in many locations and continues to be important for Hmong in Thailand in the early 1990s. Most foods are eaten boiled, and meat is only rarely part of the diet. Hmong plant many varieties of crops in different fields as a means of household risk diversification; should one crop fail, another can be counted on to take its place. Hmong also raise pigs and chickens in as large numbers as possible, and buffalo and cattle graze in the surrounding forest and abandoned fields with little care or supervision. [Source: Library of Congress, 1994 *]

In response to increasing population pressure in the uplands, as well as to government discouragement of swidden farming, some Hmong households or villages are in the process of developing small rice paddies in narrow upland valleys or relocating to lower elevations where, after two centuries as swidden farmers, they are learning paddy technology, how to train draft buffalo, and how to identify seed varieties. This same process is also occurring with other Lao Sung groups to varying degrees in the early 1990s as it had under the RLG. *

Hmong farmers who practiced slash-and-burn agriculture have generally not had title to their land. Many don’t even have citizenship rights in the countries where they live. Traditionally, the farmer who first cleared the land had the right to cultivate it. In some places where Hmong practice permanent wet rice agriculture they have land-use rights.

The Hmong have traditionally raised rice for food, maize for animal feed and opium as a cash crop. They also grow oranges and papayas on the lower slopes of mountains and peaches, apples, oats, potatoes, hemp, millet and buckwheat on the upper slopes. In some places the Hmong grow dry rice on mountain slopes that have been slashed and burned. In other placed they raise wet rice in irrigated terraces. The Hmong plant corn in swirls rather than rows, a practice that probably was conceived as a way of accommodating the irregular shaped mountain fields. To make corn flour, the kernels are crushed with a contraption that looks like a see saw.

Hmong farming is not mechanized but depends on household labor and simple tools. The number of workers in a household thus determines how much land can be cleared and farmed each year; the time required for weeding is the main labor constraint on farm size. Corn must be weeded at least twice, and rice usually requires three weedings during the growing season. Peppers, squash, cucumbers, and beans are often interplanted with rice or corn, and separate smaller gardens for taro, arrowroot, cabbage, and so on may be found adjacent to the swiddens or in the village. In long- established villages, fruit trees such as pears and peaches are planted around the houses. *

Rice is usually planted at the beginning of the wet season. For dry rice the forest is slashed and burned, and the rice is planted in fields fertilized by the nitrogenous ashes. In many cases the land is tilled with simple wooden hand plows or hoes. While rice fields have be left fallow after two or three years. Maize can be replanted for eight years. Before planting Hmong farmers taste the soil. If it is sweet (meaning its has a high lime content) then the soil is ideal for growing opium. During planting men march along poking holes in the soils with a dibble stick while women and children follow behind sowing seeds. Corn and rice is largely ground by hand. In some Hmong villages you can find a water-powered threshers that pounds rice with a sledgehammer-like devise. The mixture is then placed in water, the chaff rises to the top.

See Agriculture Under MIAO MINORITY: SOCIETY, LIFE, MARRIAGE AND FARMING factsanddetails.com

Hmong and Opium

Hmong have traditionally grown opium in small quantities for medicinal and ritual purposes. From the beginning of their colonial presence, the need for revenue prompted the French to encourage expanded opium production for sale to the colonial monopoly and for payment as head taxes. Production, therefore, increased considerably under French rule, and by the 1930s, opium had become an important cash crop for the Hmong and some other Lao Sung groups. Hmong participate in the cash market economy somewhat more than other upland groups. They need to purchase rice or corn to supplement inadequate harvests, to buy cloth, clothing, and household goods, to save for such emergencies as illness or funerals, and to pay bride-price.

Chinese traders introduced opium to ethnic minorities in Southeast Asia. The French as well as the English grew it as a cash crop. One fourth of the money the French earned in Southeast Asia was generated from opium. The French gave poppy seeds to the Hmong in Laos, and gave them advise on how to increase their opium yields. At one point about 90 percent of the Laos's total opium output was produced by the Hmong.

Opium poppies are a cold-season crop, In the isolated upland settlements favored by the Hmong they are typically planted in cornfields after the main harvest. Opium, a sap extracted from the poppy plant, traditionally has been almost the only product that combined high value with low bulk and was nonperishable, making it easy to transport. It was s thus an ideal crop, providing important insurance for the household against harvest or health crises.

In the 1970s many Hmong smoked opium on occasion, but not to the point of addiction. It was regarded as acceptable for elderly people to smoke opium and pass away the end of their life in peaceful euphoria but was considered disgraceful for young people to become addicted. National Geographic recounted a story about a Hmong man who ordered his son to stop smoking. The young man tried and failed. The father then told him to kill himself. He did.

Opium and corn are often grown together. Opium is planted in September or October and harvested after the New Year. Corn is planted in May or June and harvested in August or September before opium is planted. Some have argued that the degradation of the soil by slash and burn agriculture and Hmong indebtedness to Chinese traders forces many Hmong to grow opium, which grows well in poor soils and provides the biggest profits.

The Laos government officially outlawed opium production, but, mindful of the critical role it plays in the subsistence upland economy, has concentrated efforts on education and developing alternatives to poppy farming, rather than on stringent enforcement of the ban. It also established a special police counternarcotics unit in August 1992. Opium toleration policies in Thailand have ended. There the Hmong and other groups have been encouraged to grow alternative cash crops.

See Separate Articles: OPIUM, MORPHINE AND HEROIN AND THEIR HISTORY factsanddetails.com; OPIUM, MORPHINE AND HEROIN USE factsanddetails.com OPIUM, MORPHINE AND HEROIN ADDICTION factsanddetails.com OPIUM CULTIVATION, HEROIN PRODUCTION AND THE OPIUM AND HEROIN TRADE factsanddetails.com

Image Sources: Nolls China website San Francisco Museum, Wiki Commons

Text Sources: Primary Source: Encyclopedia of World Cultures. Other Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications. Spencer Sherman, National Geographic, October 1988; W.E. Garret, National Geographic, January 1974

Last updated October 2022