TURKS

Nomadic Turkic people in China

There are perhaps 135 million Turkic people in the world today, with only about 40 percent of them living in Turkey. They rest are scattered across Central Asia, Eastern Europe, the Middle East and northern and western China, making them one of the most widely scattered races in the world. All these people descended from a small tribe of horseman that originated in the Altai region

The word "Turk," is derived from the Chinese character “Tu-Kiu”, which means "forceful" and "strong." The Chinese believed these Turks descended from wolves and the Great Wall of China may have been built to keep them out. According to legend a gray wolf led the first Turkic tribes from their homeland in Central Asia into Anatolia.

Turks have been known throughout history for their fierceness and fighting skills. Most of the warriors in the Mongol armies were Turks. Turks also dominated the Mamluk forces and beefed up the Persian Safavid and Indian Mogul armies. Turkic tribes were a threat to the Byzantines and Persians starting in the A.D. 6th century. They absorbed Islam during the Arab invasions which began after Mohammed's death in 632.

Websites and Resources: Ottoman Empire and Turks: The Ottomans.org theottomans.org ; Ottoman Text Archive Project – University of Washington courses.washington.edu ; Wikipedia article on the Ottoman Empire Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Ottoman Empire britannica.com ; American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century Shapell Manuscript Foundation shapell.org/historical-perspectives/exhibitions ; Ottoman Empire and Turk Resources – University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkis ; Turkey in Asia, 1920 wdl.org ; Wikipedia article on the Turkish People Wikipedia ; Turkish Studies, Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkish/turkic ; Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages users.telenet.be/orientaal/turkcestan ; Turkish Culture Portal turkishculture.org ; ATON, the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University aton.ttu.edu ; The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Origin of the Turks

The first Turks were nomads who spoke an Ural-Altaic tongue similar to Mongolian, Finnish, Korean and Hungarian. Other Turkic people include the Uzbeks in Uzbekistan, Kyrgyz in Kyrgyzstan, Turkmen in Turkmenistan, Kazakhs in Kazakhstan, Mongolians, Tartars in Russia, Uighars in western China, Azeris in Azerbaijan, Yakuts in Siberia. Some even regard Koreans and Hungarians as the relatives because their languages are similar.

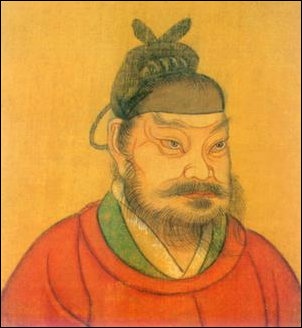

Empero Gaozu of the Later Jin Dynasty was a Turk

Denis Sinor wrote in the “Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia”: “In the 540s there appeared on the Chinese horizon a people previously barely known which, within a few years, not only changed the balance of power in Mongolia – the traditional basis of great, nomad empires – but also introduced into the scene of Inner Asian and world history an ethnic and linguistic entity which in earlier times could not be identified or isolated from other groups showing the same cultural characteristics. It bore the name Türk, an appellation left in legacy to most later peoples speaking a Turkic-language. [Source: The Cambridge History of Early Inner Asia, edited by Denis Sinor. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1990]

“It stands to reason that the Türks of Mongolia were not the products of spontaneous generation and that one must, by necessity, reckon with other Turks living there or elsewhere in centuries preceding the foundation of the empire bearing their name. Yet, such considerations notwithstanding, it should not be lost from sight that the Türks are the first people to whom we can attribute with certainty a Turkic text written in a Turkic language, and that their name – so widely used ever since their rise to power – cannot be traced with absolute certainty before the sixth century A.D.” [Ibid]

J.J. Saunders wrote in “A History of Medieval Islam”: “The Turkish family of nations first emerged into the light of history in the mid-sixth century, when they built up a short-lived nomad empire in the heart of Asia, the steppes which have ever since borne the name Turkestan, the land of the Turks. When it broke in pieces, in the manner of such confederacies, fragments of the Turkish race, under a bewildering variety of names, were scattered over a vast area, from the Uighurs, who once dwelt in Mongolia, to the Polovtsians of the Russian steppes, familiar to us from Borodin's opera Pnnce Igor. Despite the wide differences between them -- some came under Chinese, others under Persian influence -- some were pure nomads, others were settled agriculturists -- they all spoke dialects of the same tongue; they possessed common folk memories and legends; in religion they were shamanists, and they reckoned time according to a twelve-year cycle named after animals, events being placed in the Year of the Panther, the Year of the Hare, the Year of the Horse, and so on. [Source: J.J. Saunders, “A History of Medieval Islam,” (London: Routledge, 1965), chap. 9. "IX The Turkish Irruption" \=]

Ancient Turks

Altais

The Turks were such excellent horsemen the ancient Chinese called them “horse barbarians.” Turkish women reputedly could conceive and gave birth while riding. Based on excavations and stele observations in Mongolia, archaeologists say that early Turks dressed themselves in silk, wool and animal skin garments; men wore daggers in their belts and earrings in both ears; and both men and women braided their hair.

These ancient Turks raised millet, lived in felt "gers" ("yurts") like Mongolian nomads today, and worshiped a fertility goddess, a god of the underworld and their Turkish ancestors. They made swords and spears from iron and were known for their metal working skill. Some of their leaders wore armor made from golden plates.

Throughout Central Asia, Mongolia, the Altai area of Russia and western China they left behind large stone figures known as "balbals" or man stones. Dated to the A.D. 6th through 8th centuries, they are thought to be memorial erected to honor warrior who had fallen in battle. Almost all face east towards the rising sun. Most hold a sword and a bowl and wear a distinctive belt and earrings. They are often found with lines of stone slab that perhaps represent the number of men killed by person the man stone honors.

The ancient Turks were adept hunters, preying on roe deer and mountain goats, which they sometimes drove into pens. They were one of the first groups of people to use saddles with stirrups. This enabled them to swiftly attack their enemies because they could stand up and shoot their long bows while riding. Ancient Turks were so attached to their horses that rulers and warriors often had their fully harnessed mounts buried with them after they died.

Altai Turks

Turkic people trace their ancestry back to the A.D. 3rd century Altai Turks, who came from the Altai Mountains in southern Siberia, Kazakhstan, and Mongolia.

modern Altai region

The Altai (also spelled Altay) Turks were united in A.D. 552 under leadership of a chieftain named Bumin, who, with the help of the Chinese, defeated the overlords that ruled the tribes in the Altai region and then subjugated the tribes on the Mongolian steppe. Later, with the help of the Sassanid Persians, Bumin conquered Central Asia, which gave the Altai Turks control over the Silk Road trade route between China and the West.

The Altai controlled much of southern Siberia and Central Asia from the A.D. 6th century. They were one of the first Central Asian groups to realize the importance of trade and the wealth the trade brought them allowed them to establish permanent settlements.

The ancient Turks of the Altai region developed a written languages which they left in on runic stones as far away as the Yenisei Valley in Siberia to the north and Orkhon Valley in Mongolia to the east. This writing system resembled the script of early Germanic tribes. Later the Uigar script was adopted by many Turkic-speaking peoples. The Uigar script is related to the alphabets of Western Asia and was also used by the Mongols during the era of Genghis Khan.

Altai Region

The Altai Region is a mountainous area in central Asia where Mongolia, Russia, Kazakhstan and China all come together. Situated between the Gobi Desert and the Siberian Plain, it is regarded as the homeland of the of the Mongolians, Turks, Koreans and Hungarians. Ural-Altaic languages are named after the region. Ancient petroglyphs found in the area are believed to have been made the ancestors of the Altay.

The Altay region today is one of the wildest and most interesting parts of Mongolia and Russia. It is varied region with forest, steppes, wild river, lakes, deserts, snow capped mountain and abundant wildlife. On windward sides of the mountains are some of the wettest places in Mongolia, with glaciers, streams and numerous lakes. On the leeward side are some the driest areas.

Natural vegetation in the region includes steppe grasses, shrubs and bushes and light forests of birch, fir, aspen, cherry, spruce, and pines, with many clearings in the forest. These forest merge with a modified taiga. Among the animals are hare, mountain sheep, several species of deer, “bobac”, East European woodchucks, lynx, polecat, snow leopard, wolves, bears, Argali sheep, Siberian ibex, mountains goats and deer. Bird species include pheasant, ptarmigan, goose, partridge, Altai snowcock, owls, snipe and jay, In the streams and rivers are trout, grayling and the herring-like sig.

The Altai Mountains stretch for 1,200 miles across southwestern Mongolia from Siberia to the Gobi Desert. The mountains are of moderate height. There are several peaks over 4,500 meters. Those that are higher than 3,000 meters are snowcapped throughout the year. The region is rich in lakes and streams. The Ob, Irtysh and Yenisei all have their sources in the Altai. The Altai people live mainly in the broad plateaus, steppes and valleys of the ranges, where water is plentiful. The Altai complex of mountain ranges embraces the water divide mountains for all of Asia: the South Altai, the Inner Altai and the east Altai. The Mongolian Altai is connected to this mountain complex, rising to the southeast of the Siberian Altai region.

The climate is continental with extremes in temperatures between the summer and the winter. The mountains help to mitigate the extremes to some extent by causing a winter temperature inversion that produces an island of winter temperatures that are warmer than those in the Siberian taiga to the north and the Central Asian and Mongolian steppes to south and east. Even so temperatures drop as low as -48̊C in the winter. The mountains are a gathering point for precipitation in a region that otherwise is dry. The most rain falls in July and August, with another smaller period of rain in late autumn. The western Altai receives around 50 centimeters of precipitation a year. The eastern Altai receives less: around 40 centimeters a year

The archeological and historical evidence that the Altai Mountains is the original homeland of all Altaic-speaking people is a bit flimsy. The argument is based on simple geography: the fact that it lies at the center of a scattering of Turkic-speaking peoples.

In the first millennium B.C., the Altai were inhabited by pastoral nomads who domesticated sheep, horses and other animals. See Pazyryk, History

Historical and archeological evidence indicate that the people that lived here from 5th to the 1st centuries B.C. were a herding people under the rule of chief or king. These people had contact with peoples in Central Asia. The language of these people is unknown but it seems unlikely that there were Turkic speakers. Turkic speakers arrived in the Altai region at a later time, some time in the A.D. first millennium.

See Separate Article ALTAI REGION AND ALTAI PEOPLE factsanddetails.com

Early Mentions of Türks

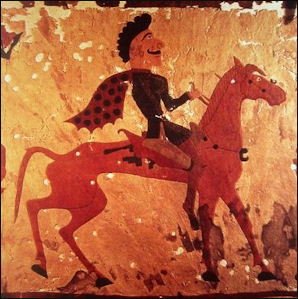

Pazyryk HorsemanIt could be that the first mention of the name Türk was made in the middle of the first century A.D. Pomponius Mela (I,116) refers to the Turcae in the forests north of the Azov Sea, and Pliny the Elder in his Natural History (VI, 19) gives a list of peoples living in the same area among whom figure the Tyrcae.

The first historical references to the Turks appear in Chinese records dating around 200 B.C. These records refer to tribes called the Hsiung-nu (an early form of the Western term Hun ), who lived in an area bounded by the Altai Mountains, Lake Baykal, and the northern edge of the Gobi Desert, and who are believed to have been the ancestors of the Turks. Specific references in Chinese sources in the sixth century A.D. identify the tribal kingdom called Tu-Küe located on the Orkhon River south of Lake Baykal. The khans (chiefs) of this tribe accepted the nominal suzerainty of the Tang Dynasty. The earliest known example of writing in a Turkic language was found in that area and has been dated around A.D. 730. [Source: Library of Congress, January 1995 *]

Other Turkish nomads from the Altai region founded the Görtürk Empire, a confederation of tribes under a dynasty of khans whose influence extended during the sixth through eighth centuries from the Aral Sea to the Hindu Kush in the land bridge known as Transoxania (i.e., across the Oxus River). The Görtürks are known to have been enlisted by a Byzantine emperor in the seventh century as allies against the Sassanians. In the eighth century, separate Turkish tribes, among them the Oguz, moved south of the Oxus River, while others migrated west to the northern shore of the Black Sea.*

Rise of the Ancient Turks

Zhuangzong of the Late Tang Dynasty was a Turk

Northern Wei was disintegrating rapidly because of revolts of semi-tribal Toba military forces that were opposed to being sinicized, when disaster struck the flourishing Ruruan Empire. The Türk, a vassal people, known as Tujue to Chinese chroniclers, revolted against their Ruruan rulers. The uprising began in the Altai Mountains, where many of the Türk were serfs working the iron mines. Thus, from the outset of their revolt, they had the advantage of controlling what had been one of the major bases of Ruruan power. Between 546 and 553, the Türks overthrew the Ruruan and established themselves as the most powerful force in North Asia and Inner Asia. This was the beginning of a pattern of conquest that was to have a significant effect upon Eurasian history for more than 1,000 years. The Türk were the first people to use this later wide-spread name. They are also the earliest Inner Asian people whose language is known, because they left behind Orkhon inscriptions in a runic-like script, which was deciphered in 1896. [Source: Library of Congress, June 1989 *]

It was not long before the tribes in the region north of the Gobi--the Eastern Türk--were following invasion routes into China used in previous centuries by Xiongnu, Xianbei, Toba, and Ruruan. Like their predecessors who had inhabited the mountains and the steppes, the attention of the Türk quickly was attracted by the wealth of China. At first these new raiders encountered little resistance, but toward the end of the sixth century, as China slowly began to recover from centuries of disunity, border defenses stiffened. The original Türk state split into eastern and western parts, with some of the Eastern Türk acknowledging Chinese overlordship.*

Early Turkish States

For a brief period at the beginning of the seventh century, a new consolidation of the Türk, under the Western Türk ruler Tardu, again threatened China. In 601 Tardu's army besieged Chang'an (modern Xi'an), then the capital of China. Tardu was turned back, however, and, upon his death two years later, the Türk state again fragmented. The Eastern Türk nonetheless continued their depredations, occasionally threatening Chang'an. [Source: Library of Congress, June 1989 *]

The Turks began their rise to power when one of their leaders was denied the hand of daughter from another tribe, the Juan Juans, who enlisted the Turk's help. The leader married a daughter of Chinese group who united with Turks to break the Juan Juans. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

The first great state which carried the name Turk was the Kok-Turk State which extended from Manchuria to the Black Sea and Iran between the A.D. 6th and 8th centuries. This empire had trade links with China, Iran and the Byzantines and left behind inscriptions and an unusual alphabet on stones in Mongolia.

The Turkish migrations after the sixth century were part of a general movement of peoples out of central Asia during the first millennium A.D. that was influenced by a number of interrelated factors--climatic changes, the strain of growing populations on a fragile pastoral economy, and pressure from stronger neighbors also on the move. Among those who migrated were the Oguz Turks, who had embraced Islam in the tenth century. They established themselves around Bukhara in Transoxania under their khan, Seljuk. Split by dissension among the tribes, one branch of the Oguz, led by descendants of Seljuk, moved west and entered service with the Abbasid caliphs of Baghdad. [Source: Library of Congress, January 1995 *]

Turks and the Arab-Muslim Conquest

J.J. Saunders wrote in “A History of Medieval Islam”: “The Oxus was the traditional boundary between civilization and barbarism in Western Asia, between Iran and Turan, and Persian legend, versified in Firdawsi's great epic, the Shah-namah, told of the heroic battles of the Iranians against the Turanian king Afrasi- yab, who was at last hunted down and killed in Azerbaijan. When the Arabs crossed the Oxus after the fall of the Sassanids, they took over the defence of kan against the barbarian nomads and pushed them back beyond the Jaxartes. The Turkish tribes were in political disarray, and were never able to oppose a unified resistance to the Arabs, who carried their advance as far as the Talas river. For nearly three centuries Transoxiana, or as the Arabs called it, Ma Wara al-Nahr, 'that which is beyond the river', was a flourishing land, free from serious nomadic incursions, and cities like Samarkand and Bukhara rose to fame and wealth. [Source: J.J. Saunders, “A History of Medieval Islam,” (London: Routledge, 1965), chap. 9. "IX The Turkish Irruption" \=]

Turkic regions and states around AD 700

“From the ninth century onwards the Turks began to enter the Caliphate, not in mass, but as slaves or adventurers serving as soldiers. They thus infiltrated the world of Islam as the Germans did the Roman Empire. The Caliph Mu'tasim (833-842) was the first Muslim ruler to surround himself with a Turkish guard. Turkish officers rose to high rank, commanding armies, governing provinces, sometimes ruling as independent princes: thus Ahmad b.Tulun seized power in Egypt in 868, and a second Turkish family, that of the Ikhshidids (from an Iranian title ikkshid, meaning 'prince'), ran the same country from 933 until the Fatimid conquest in 969. The disintegration of the Abbasid Empire afforded ample scope for such political adventurism, but so long as Transoxiana was held for civilization, the heart of Islam was safe from a massive barbarian break-through. When the Caliphs ceased to exercise authority on the distant eastern frontier, the task was shouldered by the Samanids, perhaps the most brilliant of the dynasties which took over from the enfeebled Abbasids. In the end it proved too heavy a burden, and the Samanid collapse at the end of the tenth century opened the floodgates to Turkish nomad tribes, who poured across both Jaxartes and Oxus into the lands of the Persians and Arabs. \=\

Central Asia in the Early Turkish Period

J.J. Saunders wrote in “A History of Medieval Islam”: “Despite their brief rule of little more than a hundred years, the Samanids had much to their credit. Of Persian origin, they set up a strong centralized government in Khurasan and Transoxiana, with its capital at Bukhara; they encouraged trade and manufactures; they patronized learning, and they sponsored the spread of Islam by peaceful conversion among the barbarians to the north and east of their realm. It was during their time that the vigorous and commercially-minded Vikings gained possession of Russia, and traded their furs and wax and slaves in the markets of the south in exchange for textiles and metal goods, evidence of this trafflc being provided by the hoards of Arabic coins dug up in Sweden, Finland and North Russia. [Source: J.J. Saunders, “A History of Medieval Islam,” (London: Routledge, 1965), chap. 9. "IX The Turkish Irruption" \=]

“One of the main international trade routes of the age ran through the territory of the Bulghars, a Turkish race living in the region of the middle Volga, who accepted Islam before 921, in which year a mission from the Caliph Muktadir visited them and reported on life among this most northerly of Muslim peoples. The Bulghars in turn tried to convert the Russians, but Vladimir of Kiev decided in 988 in favour of Christianity, thereby barring Islam's advance into Eastern Europe. Most probably the Bulghars were converted by merchants from the Samanid kingdom, who also brought the faith to the Turks beyond the Jaxartes, nomads who did a brisk trade in sheep and cattle with the frontier towns. About 956 the Seljuks, destined to so glorious a future, embraced Islam, and in 960 the conversion of a Turkish tribe of 200,000 tents is recorded: their precise identity is unspecified. Thus the tenth century witnessed the islamization, under Samanid auspices, of a large section of the Western Turks, an event of great significance. \=\

“Notwithstanding the prosperity of their kingdom, the Samanids failed to keep the loyalty of their subjects. Their heavily bureaucratized despotism was expensive to maintain, and the burden of taxation alienated the dihkans, on whose support the regime depended. One of their rulers, Nasr al-Sa'id, who reigned from 914 to 943, favoured the Isma'ilis and corresponded with the Fatimid Caliph Ka'im, thereby forfeiting the sympathy of the orthodox. Following the example of the Abbasids, they surrounded themselves with Turkish guards, whose fidelity was far from assured.

ancient Turk geographic map and linguistic tree of Turkic langauges

Mahmud of Ghazna

J.J. Saunders wrote in “A History of Medieval Islam”: “In 962 one of their Turkish officers, Alp-tagin ('hero prince'), seized the town and fortress of Ghazna, in what is now Afghanistan, a wealthy co mercial centre whose inhabitants had grown rich on the Indian trade and set up a semi-independent principality. He died in the following year, and after an interval another Turkish general, Sabuk-tagin, won control of Ghazna in 977 and founded a dynasty which gained immortal lustre from his son Mahmud. The Samanid kingdom fell into anarchy; the Kara-Khanids, a Turkish people of unknown antecedents (they may have been the tribe converted to Islam in 960), crossed the Jaxartes and captured Bukhara in 999, while Mahmud of Ghazna, who had succeeded his father Sabuktagin two years earlier, annexed the large and flourishing province of Khurasan. Thus Persian rule disappeared along the eastern marches of Islam, and Turkish princes reigned in Khurasan and Transoxiana. Barbarians though they might be, they found a certain favour with their subjects: they stood for order, they allowed Persian officials to run the government, they protected trade, they were orthodox Sunnite Muslims, and they professed themselves ardent champions of the faith against heretics and unbelievers. [Source: J.J. Saunders, “A History of Medieval Islam,” (London: Routledge, 1965), chap. 9. "IX The Turkish Irruption" \=]

“The fame of Mahmud of Ghazna rests upon his expeditions into India. In the thirty years between 1000 and his death in 1030 he led some seventeen massive raids into the Indus valley and the Punjab. Ghazna was an admirable base for such attacks; the vast Indian sub-continent was a mosaic of principalities great and small; no strong state existed capable of throwing back the invader, and there was no trace of national consciousness. Mahmud's motives were a mixture of cupidity and religious zeal: when he was looting Hindu shrines he could claim to be destroying idolatry in the name of God and his Prophet, and he received congratulations and honours from the Caliph for his services to the faith. He fought not only against the unbelievers of Hindustan but against the Isma'ili heretics among them the Muslim ruler of Multan. His most celebrated expioit was the capture of Somnath in Gujarat in 1025, where he stormed the temple of Shiva, one of the most richly endowed in India, and levelled it to the ground amid frightful carnage. Ghazna was flooded with Indian plunder, and the multitude of prisoners was such that they were sold as slaves for two or three dirhams apiece. Some of the wealth was used to promote art and learning, and the court of Mahmud was adorned by such notabilities as Firdawsi, Persia's greatest epic poet, Biruni, the most distinguished scientist of the age, and Utbi, the historian of the reign. \=\

“Two consequences of immense importance flowed from Mahmud's repeated incursions into India. First, the collapse of Hindu resistance in the Punjab turned this province into an area of Muslim settlement and exposed the whole Gangetic plain to invasion from the north-west. The early raids up and down the Indus in the days d Muhammad b.Kasim had only touched the fringe of a vast country but Mahmud's expeditions penetrated deep into Hindustan, disoganized its defences, and opened the way to later Muslim invaders, fom the Ghurids to the Moguls, who gradually brought all nortbern and central India within the domain of Islam. Secondly, the preoccupation of Mahmud and his son and successor Mas'ud with their Indian campaigns left them little time or opporunity to observe and check the steadily mounting pressure of Turkish nomads along the Oxus. While their backs were turned, so to speak, the Seljuks rose to prorninence and power in their rear and bcame the masters of all Western Asia. \=\

Population structure of Turkic-populations in the context of their neighbors in Eurasia

Turkish Tribes in the Middle Ages

Dominant Turkic tribes in the 10th, 11th and 12th centuries included the Uighars, Khazars, Kipchacks and Seljucks. The Mongols were slightly related to Turkic groups. One of the main differences between the Mongols and the Turks is that the Mongols tended to return home after their conquests while the Turks tended to stay in their conquered lands. The Russians lumped the Mongols, Tatar and Turks together and called them "Tatars."

All the Turkic tribes converted to Islam except for the reindeer herding Yakuts in Siberia and the Chuvash in the Volga region of Russia, but the wolf mythology stayed with them. Ninth century stelae in Mongolia show young Turkic children suckling from the teats of a mother wolf like Romulus and Remus, and the Osmanli Turks, the forbears of the Ottomans, marched with banners depicting a wolf's head when they conquered their way from Central Asia to the outskirts of Constantinople.

In the 11th Turkish tribes began invading western Asia from their homelands in Central Asia. The strongest of these tribes was the Seljuks. In the wake of the Samanids (819-1005) — Persians who set up a local dynasty in Central Asia within the Abbasid Empire — arose to two Turkish dynasties: the Ghaznavids, based in Khorasan in present-day Turkmenistan, and the Karakhanids from present-day Kazakhstan. Karakhanids are credited with converting Central Asia to Islam. The established a large empire that stretched from Kazakhstan to western China and embraced three important cities: Balasagun (present-day Buruna in Kyrzgzstan), Talas (present-day Tara in Kazakhstan) and Kashgar. Bukhara continued as a center of learning. The Karakhanids and Ghaznavids fought one another off and on until they were both out maneuvered diplomatically and militarily by the Seljuk Turks, who created a huge empire that stretched from western China to the Mediterranean.

Ancient Turkmen

Historians believe that the original Turkmen — of present-day Turkmenistan — were nomadic horse-breeding clans known as the “Oghuz” from the Altai region of what is now Mongolia and Siberia. They began migrating from their homeland around the 6th century, then were driven out by the Seljuk Turks, and formed communities in the oases around the Kara-kum deserts of modern Turkmenistan and also parts of Persia, Anatolia and Syria.

The Orguz first appeared in the area of Turkmenistan is the A.D. 8th to 10th centuries. According to legend Turkmen are descended from the fabled Orghuz Khan or the warriors who formed clans around his 24 grandsons.

The name Turkmen first appeared in 11th century sources. It referred to groups among the Oghuz that converted to Islam. During the 13th century Mongol invasions they fled to remote areas near the shores of the Caspian Sea. There they remained relatively isolated. Unlike many other Central Asian peoples, they were not influenced much by Mongol culture or political traditions.

Gokturk artifacts from 7th century Mongolia

In the 11th and 12th century Orguz-Turkmen established the Khorosan and Khorsem khanates, the core of the future Turkmen nation. In the 15th century what is now Turkmenistan was divided between the Khivan and Bukharan khanates and Persia..

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, Comptom’s Encyclopedia, Lonely Planet Guides, Silk Road Foundation, “The Discoverers “ by Daniel Boorstin; “ History of Arab People “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Islam, a Short History” by Karen Armstrong (Modern Library, 2000); and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2016