OTTOMAN SULTANS

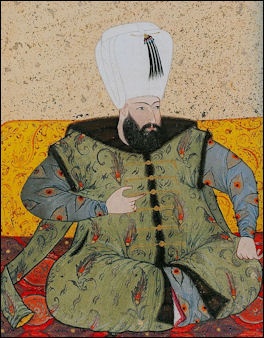

Ahmed I

The early Ottoman rulers were more like tribal chiefs that European-style monarchs, but in Constantinople they became sultans who established an absolute monarchy, based on Byzantine model, with lots of pomp and rituals.On documents the sultans were referred to as “His majesty, the victorious and successful sultan, the ruler aided by God, whose undergarment is victory.” Sometimes they were called caliph, which didn’t imply they were descendants of Mohammed as it had in the past. The government was often called “the Porte” because most government affairs were handed inside the gates of the sultans’s palace.The Ottoman sultans were revered as the caliphs of Sunni Islam” heirs to the Prophet Mohammed and the temporal and spiritual heads of Islam. They ruled from Topkapi Palace in Istanbul and expressed their will through decrees, orders and a variety of correspondence and documents stamped with the sultan’s elaborately-decorated “tugba” (“imperial monogram”). The creators of the tugba were some of the most highly-skilled artist in the Ottoman Empire.

Authority was held by the “house of Osman” rather than a single family member. There was no set rules for succession and, with a few exceptions, succession was relatively smooth and the sultans enjoyed long, relatively unchallenged reigns. Until the 17th century most sultans were succeeded by their ablest son After that it was the oldest living member of his family.

During the Ottoman equivalent of a coronation, the new sultan went to Eryup Mosque in Istabul and was girded with the sword of Osman, the founder of the Ottoman Empire. Turkish prime ministers still visit the shrine after being appointed.To mark the sultan’s ascension to the throne, a special ceremony was held in which the sualtn recived homage from his officials.

Websites and Resources: Ottoman Empire and Turks: The Ottomans.org theottomans.org ; Ottoman Text Archive Project – University of Washington courses.washington.edu ; Wikipedia article on the Ottoman Empire Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Ottoman Empire britannica.com ; American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century Shapell Manuscript Foundation shapell.org/historical-perspectives/exhibitions ; Ottoman Empire and Turk Resources – University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkis ; Turkey in Asia, 1920 wdl.org ; Wikipedia article on the Turkish People Wikipedia ; Turkish Studies, Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkish/turkic ; Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages users.telenet.be/orientaal/turkcestan ; Turkish Culture Portal turkishculture.org ; ATON, the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University aton.ttu.edu ; The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Ottoman Sultan Cruelty

15th century Hungarian Anti-Turk drawing

The Ottoman throne was technically open all sons. This meant there was wild fight among the sons to obtain the throne after an old sultan died. Once a new sultan took power he often eliminated any threats by promptly murdering all his brothers.

The Ottoman sultans could be very violent. When Mehmet the Conqueror became sultan the first thing he did was strangle his baby brother. Before Murat III died in 1695, he had 19 of his 20 sons murdered so the remaining one, Mehmet III, could ascend the throne without plots and intrigues.

According to the BBC: “Sultan Selim introduced the policy of fratricide (the murder of brothers). Under this system whenever a new Sultan ascended to the throne his brothers would be locked up. As soon as the Sultan had produced his first son the brothers (and their sons) would be killed. The new Sultan's sons would be then confined until their father's death and the whole system would start again. “This often meant that dozens of sons would be killed while only one would become Sultan. In the later centuries of Ottoman rule, the brothers were imprisoned rather than executed. [Source: BBC, September 4, 2009]

Tamerlane and the Sultans Before Suleyman the Magnificent

Europe was given a respite from Turkish threats and the Ottomans suffered a major setback , when Tamerlane (Timur) swept into Anatolia from Samarkand. He defeated the Ottomans at Angora in 1402 and captured the Ottoman sultan Bajazet I and carried him away in chains. During his 1402 campaign Tamerlane advanced as far west as the Aegean port of Smyrna (Izmir, Turkey), where he captured a crusader castle and massacred its defenders. Tamerlane was a Turk.

When Tamerlane died, the Ottomans under Murat II (ruled 1421-51) regain much of their lost territory, plus some taken by Tamerlane, and conquered Macedonia and part of Greece and Serbia (1439). Bajazet II (ruled 1481-1512) ruled over a period of relative peace. The Janissaries, who liked war because they could obtain land and loot, rebelled and helped Bajazet’s aggressive son Selim I take power.

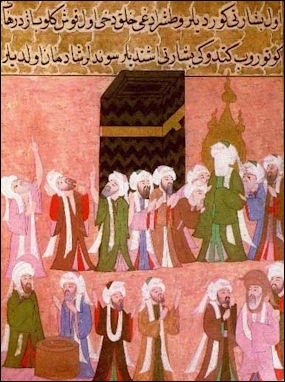

During the short rule of Selim I (ruled 1512 to 1520), the Ottomans responded to a Persian attack and moved eastward and southward under the banner of jihad inro Syria, Mesopotamia, Arabia and Egypt. Under Selim I there was a mass slaughter of dissident Muslims on the eve of the war with the Safavids in 1514. Selim I extended Ottoman sovereignty southward, conquering Syria, Palestine, and Egypt. He also gained recognition as guardian of the holy cities of Mecca and Medina.

Ottoman Rulers

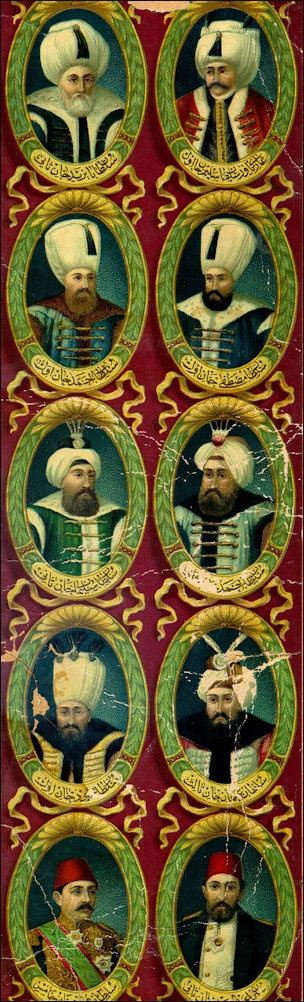

Ottoman sultans

Ottoman: 680–1342: 1281–1924

Ruler, Muslim dates A.H., Christian dates A.D.

Ertugrul: ca. 679–80: ca. 1280–81

Osman: 680–724: 1281–1324

Orhan: 724–61: 1324–60

Murad I: 761–91: 1360–89

Bayezid I: 791–805: 1389–1403

[Interregnum: 805–16: 1403–13]

Mehmet I Chelebi: 816–24: 1413–21

Murad II (1st reign): 824–48: 1421–44

Mehmet II Fatih (1st reign): 848–50: 1444–46

Murad II (2nd reign): 850–55: 1446–51

Mehmet II Fatih (2nd reign): 855–86: 1451–81

Bayezid II: 886–918: 1481–1512

Selim I Yavuz: 918–26: 1512–20

Süleyman I Kanuni: 926–74: 1520–66

Selim II: 974–82: 1566–74

Murad III: 982–1003: 1575–95

Mehmet III: 1003–12: 1595–1603

Ahmed I: 1012–26: 1603–17

Mustafa I (1st reign): 1026–27: 1617–18

Osman II: 1027–31: 1618–22

Mustafa I (2nd reign): 1031–32: 1622–23

Murad IV: 1032–49: 1623–40

Ibrahim: 1049–58: 1640–48

Mehmet IV: 1058–99: 1648–87

Süleyman II: 1099–1102: 1687–91

Ahmed II: 1102–6: 1691–95

Mustafa II: 1106–15: 1695–1703

Ahmed III: 1115–43: 1703–30

Mahmud I: 1143–68: 1730–54

Osman III: 1168–71: 1754–57

Mustafa III: 1171–87: 1757–74

cAbdülhamid I: 1187–1203: 1774–89

Selim III: 1203–22: 1789–1807

Mustafa IV: 1222–23: 1807–8

Mahmud II: 1223–55: 1808–39

cAbdülmecid I: 1255–77: 1839–61

cAbdüleziz: 1277–93: 1861–76

Murad V: 1293: 1876

cAbdülhamid II: 1293–1327: 1876–1909

Mehmet V Reshad: 1327–36: 1909–18

Mehmet VI: 1336–41: 1918–22

[Source: Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art]

cAbdülmecid II (caliph only): 1341–42: 1922–24

Kšprülü Wazirs: 1066–1122: 1656–1710

Mehmet Pasha: 1066–72: 1656–61

Fazil Ahmed Pasha: 1072–87: 1661–76

Kara Mustafa Pasha (by marriage): 1087–95: 1676–83

Fazil Mustafa Pasha: 1101–2: 1689–91

Hüseyin Pasha: 1109–14: 1697–1702

Nucman Pasha: 1122: 1710

Sultan's Life

According to the BBC: “The Sultans lived in the Topkapi Palace in Istanbul. The Sultan's life was run by rituals copied from the Byzantine court. For example, the Sultan wore his silk robes once and then they were discarded. (Many now are preserved in the Topkapi Museum.) The Topkapi Palace held many objects which were used to give legitimacy to the Ottomans and reinforce the Sultan's claim to be leader of all Muslims. The most important of these was the mantle of the Prophet Muhammad and his standard and footprint. These were brought from Egypt when Cairo fell to the Ottomans. [Source: BBC, September 4, 2009 |::|]

“It was in the Harem that the Sultan spent his life. Every inhabitant of the 230 small dark rooms in the Topkapi palace was his to command. The number of concubines often exceeded a thousand and came from all over the world. The only permanent male staff consisted of eunuchs. |::|

“Access to the Sultan meant power. But no one was to be trusted. The Sultan moved every night to avoid assassination. Favoured males were promoted to rule places far away like Syria; males not in favour could be locked up inside the palace. |::|

“The harem was a paradox, since it was a feature of the Ottoman Empire (and other Islamic states) yet contained much that was not permissible in Islam. The harem was extravagant, decadent, and vulgar. The concentration of wealth, suffering and injustice toward women was far from the ideals of marriage and married life in Islam. Despite this, the harem could bring benefits to a family who had a woman in the harem. It meant patronage, wealth and power; it meant access to the most powerful man in the Empire - the Sultan. |::|

Ottoman Pageantry and Court Life

Harem eunuch

The sultan wore armor made master craftsman and carried a ceremonial sword and canteen. The sword represented his authority as the commander-in-chief of the army and the protector of Islam. The canteen carried purified drinking water, an ancient Turkish customs that can be traced by their back to when they were horsemen on the Central Asian steppes. This sword and canteen were the equivalent to the crown and orb used by European monarchs.

The sultan regularly attended Fridays prayers at a mosque somewhere in Constantinople. He was accompanied by a large entourage. These visits were one of the few times the sultans was seen in public and could be petitioned. The sultan was attended by servants who carried his weapons and water to be used in ablutions before prayers.

Court life adhered to rigid protocol based on ancient Turkish traditions. Ceremonies included religious holidays, when subjects presented their greetings to the sultan; and receptions of foreign heads of state and ambassadors. During these events the sultan was dressed in magnificent garments and accompanied by hundreds of attendants, all dressed in richly patterned brocaded satins and velvets.

An indication that Turkish sultans were not far removed from their nomadic past, they used to set up tents in their palace gardens and dress up in horseman's caftans and seat themselves on cushions and carpets. By their sides were quivers and bow cases. When they traveled they brought their thrones of gem-encrusted gold or inlaid wood, which were constructed in several interlocking sections that could easily be assembled or disassembled.

In the sultan’s presence the entire court was supposed to remain quiet. Western visitors were often struck by how absolutely quiet large assemblies with the sultan were. Subject were often required to kiss various parts of his clothing and body depending on their rank. High officials might kiss his toes and low ranked subjects might kiss the edge of his scarf or the ground he walked on. Ambassadors who greeted the Turkish sultan had to walk backwards when the departed from the throne. No one was allowed to turn their back on the sultan.♂

Visit to the Wife of Suleiman the Magnificent

A Visit to the Wife of Suleiman the Magnificent (Translated from a Genoese Letter, c. 1550): “When I entered the kiosk in which she lives, I was received by many eunuchs in splendid costume blazing with jewels, and carrying scimitars in their hands. They led me to an inner vestibule, where I was divested of my cloak and shoes and regaled with refreshments. Presently an elderly woman, very richly dressed, accompanied by a number of young girls, approached me, and after the usual salutation, informed me that the Sultana Asseki was ready to see me. All the walls of the kiosk in which she lives are covered with the most beautiful Persian tiles and the floors are of cedar and sandalwood, which give out the most delicious odor. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song, and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 509-510.

“I advanced through an endless row of bending female slaves, who stood on either side of my path. At the entrance to the apartment in which the Sultana consented to receive me, the elderly lady who had accompanied me all the time made me a profound reverence, and beckoned to two girls to give me their aid; so that I passed into the presence of the Sultana leaning upon their shoulders. The Sultana, who is a stout but beautiful young woman, sat upon silk cushions striped with silver, near a latticed window overlooking the sea. Numerous slave women, blazing with jewels, attended upon her, holding fans, pipes for smoking, and many objects of value.

“When we had selected from these, the great lady, who rose to receive me, extended her hand and kissed me on the brow, and made me sit at the edge of the divan on which she reclined. She asked many questions concerning our country and our religion, of which she knew nothing whatever, and which I answered as modestly and discreetly as I could. I was surprised to notice, when I had finished my narrative, that the room was full of women, who, impelled by curiosity, had come to see me, and to hear what I had to say.

“The Sultana now entertained me with an exhibition of dancing girls and music, which was very delectable. When the dancing and music were over, refreshments were served upon trays of solid gold sparkling with jewels. As it was growing late, and I felt afraid to remain longer, lest I should vex her, I made a motion of rising to leave. She immediately clapped her hands, and several slaves came forward, in obedience to her whispered commands, carrying trays heaped up with beautiful stuffs, and some silver articles of fine workmanship, which she pressed me to accept. After the usual salutations the old woman who first escorted me into the imperial presence conducted me out, and I was led from the room in precisely the same manner in which I had entered it, down to the foot of the staircase, where my own attendants awaited me.

Dining With The Sultana, 1718

Lady Mary Wortley Montagu wrote in 1718: “I was led into a large room, with a sofa the whole length of it, adorned with white marble pillars like a ruelle, covered with pale-blue figured velvet on a silver ground, with cushions of the same, where I was desired to repose till the Sultana appeared, who had contrived this manner of reception to avoid rising up at my entrance, though she made me an inclination of her head when I rose up to her. I was very glad to observe a lady that had been distinguished by the favor of an emperor, to whom beauties were every day presented from all parts of the world. But she did not seem to me to have ever been half so beautiful as the fair Fatima I saw at Adrianople; though she had the remains of a fine face, more decayed by sorrow than by time. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song, and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 511-515.

Roxelana

“But her dress was something so surprisingly rich, I cannot forbear describing it to you. She wore a vest called donalma, and which differs from a caftan by longer sleeves, and folding over at the bottom. It was of purple cloth, straight to her shape, and thick-set, on each side, down to her feet, and round the sleeves, with pearls of the best water, of the same size as their buttons commonly are. You must not suppose I mean as large as those of my Lord ____, but about the bigness of a pea; and to these buttons large loops of diamonds, in the form of those gold loops so common upon birthday coats. This habit was tied at the waist with two large tassels of smaller pearl, and round the arms embroidered with large diamonds: her shift fastened at the bottom with a great diamond, shaped like a lozenge; her girdle as broad as the broadest English ribbon, entirely covered with diamonds. Round her neck she wore three chains, which reached to her knees: one of large pearl, at the bottom of which hung a fine colored emerald, as big as a turkey-egg; another, consisting of two hundred emeralds, close joined together of the most lively green, perfectly matched, every one as large as a half-crown piece, and as thick as three crown pieces; and another of small emeralds, perfectly round. But her earrings eclipsed all the rest. They were two diamonds, shaped exactly like pears, as large as a big hazelnut. Round her talpoche she had four strings of pearl, the whitest and most perfect in the world, at least enough to make four necklaces, every one as large as the Duchess of Marlborough's, and of the same size, fastened with two roses, consisting of a large ruby for the middle stone, and round them twenty drops of clean diamonds to each. Beside this, her headdress was covered with bodkins of emeralds and diamonds. She wore large diamond bracelets, and had five rings on her fingers, all single diamonds, (except Mr. Pitt's) the largest I ever saw in my life. It is for jewelers to compute the value of these things; but, according to the common estimation of jewels in our part of the world, her whole dress must be worth above a hundred thousand pounds sterling. This I am very sure of, that no European queen has half the quantity; and the Empress' jewels, though very fine, would look very mean near hers.

“She gave me a dinner of fifty dishes of meat, which (after their fashion) were placed on the table, but one at a time, and thus extremely tedious. But the magnificence of her table answered very well to that of her dress. The knives were of gold, the hafts set with diamonds but the piece of luxury that gripped my eyes was the tablecloth and napkins, which were all tiffany, embroidered with silks and gold, in the finest manner, in natural flowers. It was with the utmost regret that I made use of these costly napkins, as finely wrought as the finest handkerchiefs that ever came out of this country. You may be sure that they were entirely spoiled before dinner was over. The sherbet (which is the liquor they drink at meals) was served in china bowls; but the covers and salvers were massy gold. After dinner, water was brought in a gold basin, and towels of the same kind as the napkins, which I very unwillingly wiped my hands upon; and coffee was served in china, with gold sou-coupes.

“The Sultana seemed in very good humor, and talked to me with the utmost civility. I did not omit this opportunity of learning all that I possibly could of the seraglio, which is so entirely unknown among us. She never mentioned her husband without tears in her eyes, yet she seemed very fond of the discourse. "My past happiness," said she, "appears a dream to me. Yet I cannot forget that I was beloved by the greatest and most lovely of mankind. I was chosen from all the rest, to make all his campaigns with him; I would not survive him, if I was not passionately fond of my daughter. Yet all my tenderness for her was hardly enough to make me preserve my life. When I lost him, I passed a whole twelvemonth without seeing the light. Time has softened my despair; yet I now pass some days every week in tears, devoted to the memory of my husband."

“There was no affectation in these words. It was easy to see she was in a deep melancholy, though her good humor made her willing to divert me. She asked me to walk in her garden, and one of her slaves immediately brought her a pellice of rich brocade lined with sables. I waited on her into the garden, which had nothing in it remarkable but the fountains; and from thence she showed me all her apartments. In her bed chamber her toilet was displayed, consisting of two looking-glasses, the frames covered with pearls, and her night talpoc1te set with bodkins of jewels, and near it three vests of fine sables, every one of which is, at least, worth a thousand dollars (two hundred pounds English money). I don't doubt these rich habits were purposely placed in sight, but they seemed negligently thrown on the sofa. When I took my leave of her, I was complimented with perfumes, as at the grand vizier's, and presented with a very fine embroidered handkerchief. Her slaves were to the number of thirty, besides ten little ones, the eldest not above seven years old. These were the most beautiful girls I ever saw, all richly dressed; and I observed that the Sultana took a great deal of pleasure in these lovely children, which is a vast expense; for there is not a handsome girl of that age to be bought under a hundred pounds sterling. They wore little garlands of flowers, and their own hair, braided, which was all their headdress; but their habits all of gold stuffs. These served her coffee, kneeling; brought water when she washed, etc. It is a great part of the business of the older slaves to take care of these girls, to teach them to embroider and serve them as carefully as if they were children of the family.”

Ottoman Imperial Clothes

The Ottoman ceremonial kaftan was a floor-length, loose robe with long sleeves that reached the ground. Vertical slits in the shoulders allowed the arms to pass through and exposed the sleeves of the inner kaftan. Accessories consisted of gold ornaments attached to tall turbans, ivory or mother-of -pearl belts, and embroidered handkerchiefs. [Source: National Gallery of Art, Washington]

Kaftans made of luxurious textiles woven of shimmering silk and metallic thread were greatly valued; they were preserved in the treasury and presented to esteemed visitors, officials and artists. The most sumptuous fabrics were woven in the imperial workshops attached to the palace, while others for domestic use and foreign export were produce in Bursa, a center famous for its textile industry.

In the Ottoman court brocaded fabrics and embroidered silks were used to upholster benches, cover quilts and bolsters, and furnishings fashioned of textiles were also used in the field, re-creating the opulence during military campaigns and hunting expeditions. After the death of a sultan, his ceremonial garments and objects were carefully registered in the treasury, while other personal items were placed in his mausoleum

Topkapi Palace

Topkapi Palace (overlooking the Bosporus and the Golden Horn) is maze of buildings, gardens and courtyards, surrounded by a massive wall, 30 feet high and 20 feet thick. Taking up a good portion of Old Istanbul, Topkapi was the home of the 25 Turkish sultans from the 15th to 19th century. The Ottoman Empire was one of the richest empires ever and the treasures it accumulated over 450 years are all displayed right here in a series of museums that are among the best in the world. The palace was originally called the New Imperial Palace. But later the name was changed to Topkapi Sarayi (“Palace of the Cannon Gate”). [Sources: Stanley Meisler, Smithsonian; Dora Jane Hamilton, Smithsonian, February 1987; Merle Severy, National Geographic, November 1987]

The first part of the palace was built between 1459 and 1465 by Mehmet the Conqueror, shortly after the Ottomans claimed Istanbul, on a 175 acre wedge-shaped promontory formally occupied by a Byzantine acropolis. At the height of the Ottoman empire in the 17th century, Topkapi hosted parties with 40,000 people. As the sultans became increasingly Westernized they began to scorn Tokapi and spent less time there. In 1853, the sultans moved to Dolmabahçe and Topkapi became a rest home for aged concubines and slaves.

Studies by Gulru Necipoglu, an expert on Islamic art and architecture at Harvard, have shown that the layout of Topkapi resembles a traditional tent encampment used when the sultan lead his armies in battle. Power was demonstrated by accessibility to the sultan, who was protected by walls and courts. Foreigners were generally only allowed in the outer courts while trusted aids and family members were allowed into the inner courts where the sultan lived, now occupied by the Treasury.

Visitors enter Topkapi through a gate in back of Aya Sofya, where the heads of executed traitors were displayed in Ottoman times. Visitors then buy tickets in a courtyard that only the sultan could ride through on horseback. The tickets are taken in another gate, where yet more heads were displayed. The first, outer, court contains a wooded garden. The second court features a magnificent courtyard and a garden shaded with plane trees and cypresses. The third courtyard holds the Hall of Audience, the Library of Ahment III.

Rooms of Topkapi Palace

The lay out Topkapi resembles that of a small city. There are gardens, offices, residences, halls, quarters for soldiers, bureaucrats, and servants, workshops and kitchens that at first glance seem to be organized with no real rhyme or reason. The outer walls resemble those of a European castle but inside there is no grand palace, where the sultan lived, but rather a complex collection of pavilions, rooms, buildings, gardens and courtyards.

Topkapi kitchen

The Palace Kitchen (right of the second court, near the entrance gate) is where meals were sometimes prepared for 8,000 people with recipes that called for 500 lambs. The food for these massive banquets were delivered by relays of slaves and prepared by a regular staff of 17 butchers, 23 yoghurt makers, 17 chicken handlers, 27 candlemakers and six people in charge of supplying ice and snow for summer drinks. On display now are ladles the size of pots and pots large enough to boil African explorers.

Next to the kitchen are rooms and rooms of Chinese porcelain, a collection scholars say is surpassed only in Beijing and Dresden. Many of the dishes are made of greenish celadon, a ceramic material the sultans thought would change color in the presence of poisoned food. The are also displays of silver and crystal here.

In the rooms off the courtyard around the Harem today there are silk brocade ceremonial caftans, stitched together with gold and silver thread; other imperial costumes worn by the sultans and their family; silk carpets; armor, musical instruments; postage stamp-size Koran manuscripts; talismanic shirts with Koranic scriptures used to ward off evil spirits; paintings of sultans and their battles; medieval manuscripts; and 15th century clocks and celestial instruments. In one museum you can see a poem penned by Süleyman the Magnificent with gold flaked ink that reads, "I AM THE SULTAN OF LOVE."

The nomad-tent-shaped council chamber is where the sultan listened in on the meetings of his viziers. In the throne room ambassadors greeted the sultan after walking past 2000 bowing officials. Other buildings include the executioners room, stables, artist's studio, school for officials, the armory and the training room for elite troops. Baghdad Kiosk and Revan Kiosk are set in a garden where the sultans relaxed among fountains and luxurious carpets and furniture.

Treasury of Topkapi Palace

Topkapi diamond

The Topkapi Treasury houses a stunning assemblage of gems equaled only by the Crown Jewels in Britain and the Shah's treasures in Iran. The buildings now occupied by the treasury are where the sultan lived. Some of the museum's treasures, such as rotating music boxes and solid silver elephants from India, were gifts from foreign dignitaries to the sultans. Some, like the gem encrusted Korans, were gifts from pashas under the sultan controls. And others were spoils of war.

Yet others were crafted by palace craftsmen and artists. Among the 575 artisan who worked at the palace in 1575 were goldsmiths, engravers, furriers, potters, musical instrument makers, calligraphers, weavers, painters and bookbinders from Turkey, Herat, Tabriz, Cairo, Bosnia, Hungary and Austria. The sultans often oversaw the work by the craftsman The sultans were all trained in a particular trade and sometimes produced their own works of art.

Treasures in the Treasury include silver and gold belts lined with emeralds the size of quail eggs; shields rimmed with pearls and precious stones; exquisitely carved mirrors of ivory; and quivers made of silk and yet more gems. Even the water canteen the sultan took with him to battle is something to behold. It is made of 4.5 pounds of gold and imbedded with rubies, emeralds and diamonds. Not all the red stones in the treasury are real rubies and not all the clear ones are diamonds.

Other goodies in the treasury include the diamond encrusted armor of Mustafa III, an 18th century gold hookah, and a jewel encrusted cradle where newborn princes were presented to the sultan. There is a jade mug encrusted with rubies and emeralds and a figure of a sultan carved from an enormous pearl. The 86-carat diamond inside a glass vault, the story goes, was found by a fisherman, who traded it for three spoons. The reliquary of St. John the Baptist's arm has a square opening so you can see the bone inside.

The 16th century walnut, ivory and ebony throne was used by Sulyeman the Magnificent. Inlaid with gold, jewels, mother of pearl and tortoise shell, it is appreciated more for its detailed craftsmanship than European sumptuousness. It was made with special cushions so the sultan could sit cross legged on it.

Emerald Treasures and Islamic Relics at Topkapi

Topkapi dagger

The emerald treasures in the Treasury are especially dazzling. These include an emerald-plated snuff box and a gold writing box with emeralds and rubies. The 18th century emerald-studded dagger featured in the Orson Wells film has three golf-ball size emeralds and rows of diamonds on the handle. A forth large emerald conceals a small clock. The dagger was originally meant to be a present for the Nadir Shah of Iran. He was assassinated before the gift could be presented to him so the sultan kept it.

The emerald pocket watch was also supposed to be a gift from the Turkish sultan to the ruler of Persia, but the messenger died before he got to Iran and somehow the watch made its way back to Istanbul. Most of the magnificent emeralds came from Columbian mines via Spain and India in the 17th and 18th century. "Diamond-loving Europeans were at first not very found of emeralds," says gemologist Fred Ward, " which is one reason why the Ottomans...ended up with so many monstrous stones."

In the Pavilion of the Holy Mantle (center of the third courtyard), through another series of gates, you can see treasures looted from Mecca and Medina, when Ottoman sultans were the protectorate of Islam's holiest cities. Inside one display case is a tooth and a couple of strands of hair purported to be from the Prophet Mohammed himself. You can also lay eyes upon a couple of his swords and his massive Shaquille-O'Neal-size footprint. In another chamber is a part of the silver casing from the black stone of the Kaaba, an artifact that is as holy to Muslims as the True Cross or the Holy Grail is to Christians. An imam, or Muslim holy man, is inside a glassed off chamber with many of these relics, chanting prayers around the clock, something you won't see in Louvre or the Hermitage. The collection is housed in the Privy Chamber, where the sultan lived and kept his throne among gleaming domes and walls decorated with Iznik tiles. The light is kept dim out of respect to the holy objects kept here.

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples “ by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures “ edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994). “ Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018