BULGARIA AND ROMANIA BREAK AWAY FROM THE OTTOMANS

Bulgarian soldiers

Balkan nationalism rose in the late 19th century and the Russians stepped in to offer their assistance. The Romanians won their independence from the Turks in 1859. Two Romanian provinces united and became virtually independent in 1866.

Russian Tsar Alexander II helped Bulgaria to gain independence from Ottoman Turkey in the 1878 Russo-Turkish War. Bulgarian peasant guerillas with cherry-log canons, assisted by Imperial Russian troops, many of whom fell in battle, finally liberated Bulgaria from the Ottoman Empire. Some 200,000 Russian soldiers died fighting for Bulgaria. The Turks were a rivals of Russia.

The Bulgarians became independent in 1878. Two Bulgarian districts united and formed an autonomous state in 1885. Russian help was particularly instrumental in the Bulgarian defeat of the Turks. In 1908, Bulgaria and Romania declared their formal independence. The Turks withdrew from Crete in 1898. It was incorporated into Greece in 1913.

The Turks lost Albania and Macedonia and it remaining territory in Serbia, Greece, Montenegro and Bulgaria by 1912. Italy took the Dodocene islands in 1912. Having earlier formed a secret alliance, Greece, Serbia, Montenegro, and Bulgaria invaded Ottoman-held Macedonia and Thrace in October 1912. Ottoman forces were defeated, and the empire lost all of its European holdings except part of eastern Thrace. *

Websites and Resources: Ottoman Empire and Turks: The Ottomans.org theottomans.org ; Ottoman Text Archive Project – University of Washington courses.washington.edu ; Wikipedia article on the Ottoman Empire Wikipedia ; Encyclopædia Britannica article on the Ottoman Empire britannica.com ; American Travelers to the Holy Land in the 19th Century Shapell Manuscript Foundation shapell.org/historical-perspectives/exhibitions ; Ottoman Empire and Turk Resources – University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkis ; Turkey in Asia, 1920 wdl.org ; Wikipedia article on the Turkish People Wikipedia ; Turkish Studies, Turkic republics, regions, and peoples at University of Michigan umich.edu/~turkish/turkic ; Türkçestan Orientaal's links to Turkic languages users.telenet.be/orientaal/turkcestan ; Turkish Culture Portal turkishculture.org ; ATON, the Uysal-Walker Archive of Turkish Oral Narrative at Texas Tech University aton.ttu.edu ; The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

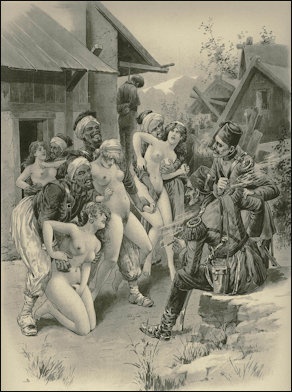

Turkish Atrocities in Bulgaria

During the war of liberation in the 1870s a journalist from Ohio entered Bulgaria on horseback and found mounds of the decomposing bodies and was told about babies skewered on bayonets, women repeatedly raped in front of their children, and surivors forced to carry the heads of decapitated relatives. Most of this was done by “bashi-bazouks”, the notorious Ottoman irregulars. [Source: Boyd Gibbons, National Geographic, July 1980]

Accounts of Turkish atrocities against civilians in the 1870s were originally thought to be exaggerated but later it was determined they were understated. A Bulgarian revolt in August 1876 was brutally put down by Turkish troops, especially ill-disciplined irregulars known as Bashi-Bazouks. News coverage of the event led to the creation of the autonomous state of Bulgaria.

Bulgarian martyresses, a painting by Konstantin Malovsky that raised awareness of what was going down in Bulgaria

Describing Turkish atrocities after a Bulgarian revolt in August 1876, Daily News Correspondent J.A. MacGahan wrote, “Down in the bottom of one of these hollows we could make out...the village of Batak, which we were in search of. The hillside were covered with little fields of wheat and rye, that were golden with ripeness. But although the harvest was ripe, and over ripe...there was no sign of reapers trying to save them.

“As we approached our attention was directed to some dogs on a slope overlooking the town...They barked at us in an angry manner, and then ran off into adjoining fields. I observed nothing peculiar as we mounted, until my horse stumbled, When looking down I perceived he had stepped on a human skull partly hid among the grass. It was quite dry and hard, and might to all appearances, have been there for two or three years, so well had the dogs done their work. A few steps further there was another, and beside it part of a skeleton, likewise white and dry. As we ascended, bones, skeletons and skulls became more frequent, but here they had not been picked so clean, for there were fragments of half-dry, half-putrid flesh still clinging to them.

“At last we came to a kind of plateau...We rode...but all suddenly drew rein with an exclamation of horror, for right before us, almost beneath our horses feet, was a sight that made us shudder. It was a heap of skulls, intermingled with bones from all parts of the human body, skeletons, nearly entire, rotten clothing, human hair and putrid flesh...It emitted a sickening odor, like that of a dead horse...In the midst of this heap I could distinguish one slight skeleton form still enclosed in a chemise...the bony ankles encased in the embroidered footless stockings worn by Bulgarian girls. We looked around us. The ground was strewed with bones in every direction, where the dogs had carried them off to gnaw them at their leisure.”

Ottoman-Inflicted Horror in a Bulgarian Village

J.A. MacGahan continued: “There was not a roof left, not a wall standing: all was a mass of ruins...On the other side of the way were the skeletons of two children lying side by side, partly covered with stones, and with frightful saber cuts in their little skulls. The number of children killed in these massacres is something enormous. They were often spitted on bayonets, and we have several stories from eye witnesses who saw little babies carried about the streets...on the points of bayonets.The reason is simple. When a Mahometan has killed a certain number of infidels, he is sure of Paradise, no matter what his sins may be. Mahomet probably intended that only armed men should count, but the ordinary Mussulman takes the precept in broader acceptation, and counts women and children as well.”

Ottoman atrocities

“Here in Batak, the Bashi-Bazouks, in order to swell the count ripped open pregnant women, and killed the unborn infants. As we approached the middle of town, bones, skeletons and skulls became more numerous. There was not a house beneath the ruins which we did not perceive human remains...A few steps further saw a woman on a doorstep, rocking herself to and fro, and uttering moans heartrending beyond anything I could have imagined...Her fingers were unconsciously twisting and tearing her hair as she gazed into her lap, where lay three little skulls with the hair still clinging to them.

At the church “we discover what appeared to be a mass of stones and rubbish is in reality an immense heap of human bodies covered over with a thin layer of stones. The whole of the little church yard is heaped up with them to a depth of three or four feet, and its from here that a fearful odor comes. Some weeks after the massacre, orders were sent to bury the dead. But the stench at the time had become so deadly that it was impossible to execute the order, or even to roam in the neighborhood of the village.

“Now could be seen projecting from the monster grave, heads, arms, legs, feet and hands, in horrid confusion. We were told there were three thousand people lying here in this little churchyard alone, and we could well believe it. It was a fearful sight—a sight to haunt one through life. There were little curly heads there in that festering mass, crushed down by heavy stones; little feet not as long as your fingers on which the flesh was dried hard...little hands stretched out as if to help; babes that had died wondering at the bright gleam of sabers as the red hands of fierce-eyed men who wield them.”

Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks in Macedonia, 1907

The Bashi-Bazouks were irregular soldiers in the Ottoman army. They had nasty reputation of being particularly cruel and brutal. Arthur D. Howden-Smith wrote in “An Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907": “We slipped into the courtyard and stood in a group about Mileff, while he whispered his instructions for the night to the several sub-chiefs. The small inclosure was packed with men in long cloaks, which were blown aside by the wind now and then, revealing glistening rifles and belts of serried cartridges. But they were quiet—unnaturally quiet. None spoke above a whisper, and the sandals made no noise on the stones.I noticed that perfect comradeship prevailed. The chetniks crowded up to the knot of chiefs and craned over their shoulders like children, eager to hear what was being discussed. They readily made way for me, and the militiamen whispered among themselves, pointing at my smooth face,—considered an affliction in Macedonia; —"Americansky," they muttered. Others crowded up to see the strange being from another land, and soon I found myself in the heart of the cheta—which was what I wanted. Mileff turned and introduced me briefly to the chief of the militiamen, a big, lusty fellow, who gripped my hand in his sinewy fingers, and muttered, "Nos dravey," a phrase that means something like "Your good health, sir." [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 421-435]

Bashi-Bazouk

“The sub-chiefs of the cheta, Nicola and Andrea, grinned at me joyfully. They were more like children than ever. In chuckling murmurs, they tried to describe to me what was going to happen to the Bashi-bazouks. Mileff laughed at them and pulled me aside. "We march at once," he explained. "Until we reach Osikovo, we shall keep together. At Osikovo, we shall divide. Andrea, with ten men, will circle the village and come down on it from the hills in the rear. The rest of us will attack from the front." He turned to the chetniks. "It is time. Where is the guide?"A tall youth pushed his way through the throng, tossing a Männlicher over his shoulder. "I am the guide, voivode," he said, saluting respectfully. I could not help observing that white the chetniks were as familiar with their chief as with each other, to the militiamen he was a superior person, one who had not only attained fame and dignity, by the blows he had dealt the Turks, but who had been across the mountains to the Frank towns, where he had learned much wisdom out of books. It is strange how a people with whom books are rare look up to the possessors of them. I have seen villagers sit for hours, listening to Mileff reading from one of the Russian authors. But all this is far from the courtyard of the house in Kovatchavishta. Mileff spoke a sharp word of command to the chetniks and militiamen, and they fell into single file behind him, the chetniks being scattered at intervals among the more numerous militiamen. Gurgeff took down the great wooden bar which held the gate, and the guide glided out. Giving him five seconds' lead, Mileff followed and the rest of the long line behind him. There was no moon in the sky, so we had to absolutely feel our way along the village street. If one had a sharp ear, it was possible to keep out of the brook-sewer that occupied the middle of the road; otherwise, the result was unpleasant.There was never a noise in the sleeping village. This time the dogs had been securely muzzled. Looking back along the line, one could only realize the presence of the cheta by occasional vague sounds and moving dots, that appeared and disappeared in the darkness. I could not see the guide at all, but Mileff, just ahead of me, with his cat's eyes, had no difficulty in following him. Soon we had left the village behind, and began the ascent of the rocky hills that rose abruptly above the house-tops. It was the same road we had ascended previously, and if it had been hard to climb down, it was twice as difficult to climb up.

“Many times we stopped for necessary rest, and each time I marveled that the Bashi-bazouks had possessed the courage to dare such a journey for a few trivial cattle. Near the head of the trail, we were challenged sharply by a squad of figures that rose suddenly from the shelter of a boulder.By the light of a star or two in the gloomy black heavens, we could see their rifle-barrels thrown athwart the stones, and we halted. They were the militia patrol, who mounted guard at the head of the mountain-road day and night, to ward against the coming of the askars. The Bashi-bazouks who had come the week before had been allowed to pass because their small numbers were a guaranty that they could not do much harm.

Bashi Bazouks smoking a nargile

“Against a larger force, the village would have risen to the last man. At a word from the guide, supplemented by an exclamation from Mileff, the patrol lowered their rifles and stood forth in the murk while we passed. To each one of us they spoke a hasty word of greeting, and then they sank back into the oblivion of the rocks, and we toiled on over; a wide moor, covered with long grass that concealed the hollows, into which one's feet slipped unawares. Sometimes the moors broke into sudden declivities, down which we half climbed, half slid. Stretches of sandy soil intervened, through which we ploughed heavily. The pace was a rapid one, for Mileff wished to get into position before midnight. Once, standing on a sort of tor that rose above the moor, I glanced backward at the line of figures that undulated as far as I could see, each one shrouded in its long sheepskin cloak, from which projected a rifle-barrel. It was marvelous how quiet and swift they were, moving over that rough, wild country, with not even a trail to guide them. Light-footed and sure of their movements as goats, they made no difficulty out of what required all my nerve and watchfulness.

“Several times we stopped for a few minutes, while the guide went ahead to reconnoiter the way. Again, on a couple of occasions it was necessary to make detours around villages. Another time, we marched straight through a collection of huts—a small outlying Christian village. We made no noise and did not waken anyone, however. We had been marching for perhaps three hours, when we came to a rude stone wall, sure sign that a village lay just beyond. Mileff called softly to the guide and held a brief consultation with the sub-chiefs, after which we proceeded more slowly. It was plain that we were entering a valley. The hills began to shut in on either side, and in front of us they narrowed so as to become a defile. Mileff detached a couple of men on the flanks to act as scouts, and we cautiously approached the portals of the valley, marching over a wagon-road, deserving of the name because deep ruts could be felt in its surface.Presently loomed up in the distance a roof. Other roofs came into view, and yet others. I leaped upon a boulder and, looking down the valley, saw a long succession of roofs sloping up the hillside to the right of the road. We continued along the road, keeping just outside of the village. Dogs barked at intervals, but otherwise the silence was absolute. At a point opposite the center of the village we halted, and Andrea passed down the line, picking out ten men whom he motioned to follow him. Without a word of farewell, they marched off into the night.The rest of us lay down behind the wall and waited. I pulled my watch out and borrowed Mileff's electric hand-lamp. It was five minutes past midnight. The chetniks arranged their knapsacks under their heads, wrapped themselves in their cloaks, taking care to protect the breeches of their rides from the moisture, and dozed off. But the militiamen did not sleep. They leaned on elbows and murmured to each other. You could see in their shining eyes the excitement that the prospect of the fight brought. With the chetniks it was too old a story to deprive a man of a nap.

Joining Local Rebels in the Fight Against the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907

Arthur D. Howden-Smith wrote in “An Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907": “For a long time, it seemed, nothing happened. The dogs barked infrequently, not at anything in particular, but just to make a noise. A wind sprang up that rustled the grass, and the leaves of the trees beside the road rattled against each other, drearily. In the distance, a nightbird croaked. Gradually, without knowing it, I dropped off to sleep, even as I had when we were waiting at the frontier line for the Turkish patrol to pass. I could not have closed more than one eye, for almost at once, I was awakened by the glare of Mileff's searchlight, inside his cloak. He was looking at his watch. I looked at mine. It was nearly one. Mileff rolled over and prodded me; taking the signal, I prodded the man next to me. So it passed down the line. We all rose to our knees and reslung our knapsacks. Still, there was not a sound. The trees across the way seemed to be moaning louder. Could the wind have so increased in force? I noticed that Mileff was holding one hand to his ear. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 421-435]

Bulgarian sentries keeping guard in the snow

“He drew a whistle from his pocket and blew gently on it. There came, from right beside me, the low whining note of the wind blowing through the tree-boughs. From beyond the trees it was answered. And I understood. Andrea and his men were signaling to us from the mountain-side.Mileff merely raised one hand, and our line swung over the stone wall into the road. Bending double, the men ran across it to the wall that lined the opposite side, surmounted it, and broke through an orchard at a run. In five minutes we were speeding along the main street of Osikovo. It was fairly sandy, and so we made little noise. The guide kept ahead, but otherwise there was no attempt at formation. Behind Mileff and me, the rest huddled together like fox-hounds in full cry. We dodged around a corner and pulled up in a little square where three streets intersected. At each corner was a house. They were all massive structures, built of stone, with slate roofs, and stood in courtyards, of which they formed one wall. One house was slightly larger than the other two, and it was immediately in front of us. There was something sinister about the blank surface of its lower walls, and the small barred windows of the two upper stories. The gateway was high, broad, and arched. The gate, itself, appeared to be substantially built of wooden beams, bolted together with iron. A huge iron lock fastened it to the side of the arch.Our line huddled in the shadows cast by the two other houses, and the guide stepped across the roadway to the gate. Lifting his carbine, he pounded vigorously for a minute upon the beams. In the stillness of the village, the blows were as distinct as the reports of a Gatling. They seemed to echo and re-echo from the archway. I fancied that in the house behind me I could already hear people waking up and moving around. A second time the guide pounded the gate. Just why, I could not say, but I was certain that I could now hear, all around me, the sounds made by people roused from sleep. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 421-435]

“Osikovo was awakening. From the other side of the gate came a shuffling of feet, and a voice demanded hoarsely what the caller wanted. "We are friends," answered the guide, his rifle at his shoulder. "We are Pomaks from Libyaho. Let us enter. We have passed chetniks in the hills." He spoke hurriedly, in the Turkish dialect. The Bashi-bazouk in the yard seemed to hesitate. "I must see your face," he said, at last. "I must see you—you and your friends—before you may enter, for it is seldom that friends come to their friends' houses after dark, and if you be friends, you will not mind the wait."Breathlessly, we waited to see what would happen. There was a creaking noise and a wicket, a hand's-breadth in size, swung open midway up the gate. Through it was stuck a rifle-barrel. The guide had shrunk to the ground, out of the range of fire. Of the Bashi-bazouk we could see nothing, because the wicket was small, and the yard beyond dark. "Stand forth," said the voice. "Stand forth, now, you and your friends, that I may see you." As luck had it, Dodor moved beside me, uneasily, and a wandering star-gleam caught, for an instant, on the steel of his bayonet. The watchful eye of the Bashi-bazouk at the wicket saw, and his rifle settled rigidly into line, while Dodor collapsed noiselessly to one side."You are armed," spoke the Bashi-bazouk. "Who are you that come armed ? Are you friends, as you say, or foes? Speak, quickly, for I do not wait long." "It is useless," breathed Mileff. "They are too suspicious. We will charge, openly." He placed the whistle at his lips, and the quivering, penetrating sigh pierced the night. The Bashi-bazouk's rifle jerked upward, and he shouted hasty words in Turkish, which I did not understand.

Firefight During the Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907

Serbian forces prepare to attack

Arthur D. Howden-Smith wrote in “An Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907": A door crashed shut in the house above him, and feet sounded on the stairs. "Charge!" cried Mileff, leaping to his feet. "Viva Makedonia!"We bunched across the road at a run, firing our rifles at the gate. I had a glimpse of the guide shooting through the wicket at the Bashi-bazouk warder, and the next thing I knew, I was in a mass of pushing, shoving men, jabbing the tough wood with bayonets, hammering on it, and even using their bare hands. Then Mileff's voice rose from the ruck. "Stand back, stand back!" he called. "Fire at the lock! Aim at the lock, every man!"Ten or a dozen rifles were concentrated at the lock, and in a trice it was blown to atoms, the gate swinging slightly ajar. For a second we paused, hesitating. A young militiaman leaped forward, put his shoulder to the timbers, and sent the portal to one side. We cheered confusedly, and ran across the yard at the doorway that showed in the irregular stone wall. From a line of windows in the upper story came a spattering fire, accompanied by sheets of flame. The chetniks fired back, crouching behind whatever cover was available. I saw one man put a bullet into a bullock, and use the carcass as a shield. Mileff and several others were in front of the house-door, shooting into the lock. It was a matter of less than a minute to smash it in, but stout bars of wood held the framework in place. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States,and Turkey, pp. 421-435]

“In the meantime, the fight was going rather against us. One of the militiamen crawled out of the gateway, dragging a limp leg behind him, and we could not see that our fire was making any impression. Quick to see the need for some new action, Mileff seized a huge balk of timber lying by the doorstep, and with Nicola and a couple of others, backed off a pace or two. Taking a short run, they brought it against the door with a mighty swing. The timbers groaned. Again they battered it, with short, fierce strokes, and because of their height from the ground, and consequent inability to see what was going on directly beneath them, the Bashi-bazouks could not effectively interrupt the maneuver.With every blow, the door tottered more helplessly.

“We saw that it must come down. But where were Andrea and his men? We needed them badly at this time. The voivode blew his whistle, as the battering-ram was swung the last time, and the door fell inward, opening up a cavernous hollow of blackness. Our own men were on hand, crouched against the house-wall, out of the Bashi-bazouk's line of fire. So we stayed, for what seemed several minutes, though it must really have been less.A cheer, the pattering of sandaled feet on the road out-side, and a renewal of firing by the askars overhead, heralded the approach of Andrea's force. They descended upon the rear of the Bashi-bazouks' fortalice. This was our chance. Not a man waited for orders. They did not need them. They sprang at the steep stairs, hardly more than a ladder, that led up to the second floor, like a gang of wolves. It did not seem as if anything could stop them. A couple of the more cautious ones, crowded out in the intensity of the first stampede, waited behind, pumping bullets up through the trapdoor, over the heads of the leaders. It was lucky they did stay back.

Ambush During the Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907

Arthur D. Howden-Smith wrote in “An Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907": “The first man through the trap was the chief of the militiamen. He bounded lightly up the stairs and disappeared from view. A revolver cracked, and as Mileff, behind him, reached the trap, his body fell backward, sweeping his comrades from the stairs as effectually as a broom. The head of a Bashi-bazouk showed for an instant, but Kortser took aim and the Turk came down on top of the pile of chstniks. It was a mess, indeed. Outside, Andrea's men were occupying the attention of the Bashi-bazouks by a steady fire at the windows, and the couple of us who had stayed below fired up the stairs as fast as we could work the ejectors. Our fire stopped the first rush, and the scanty numbers of the Bashi-bazouks did not allow them to take full advantage of the situation, so that by the time Mileff had leaped from under the pile of chetniks at the stair foot, a semblance of order had been restored.I don't know how it happened, but something had been set afire in the pent-houses by the courtyard walls that served as stables, and they were blazing vividly, lighting up the entire village. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States,and Turkey, pp. 421-435]

Bashi Bazouks escaping with war plunder

"Frightened sheep, cattle, goats, and horses ran about the yard, and the corpse of the Bashi-bazouk warder lay in a twisted heap by the gate, not far from a chetnik, whose body was simply drilled with bullet-holes. Certainly, it was a mad scene. And all about us was the village, blank and apparently tenantless, save for a prolonged wailing that rose from the scores of waiting women and children, who wept in fear of their fate. Gazing at the confusion that filled the courtyard, and deafened by the constant popping of rifles upstairs and out of doors, I did not at once hear Mileff's voice when he spoke to me. His face was black with powder, and his beard, partly singed off, was flecked with blood. He pressed his mouth close to my ear. "This is no use," he shouted. "We must retire." He beckoned to the men, and crouching close to the ground, we ran across the courtyard, in the blinding glare.

“Bullets spat in the dust on every side, but no one was hurt. The dancing of the flames, constantly tossing back and forth, filled the yard with conflicting lights and shadows that made good shooting impossible. Beyond the gate we halted, and the men dropped down, exhausted. Dodging a crazy horse which ran screaming through the street, I hastened to the group that had swiftly formed about the voivode. Andrea and his men, in line, carrying their rifles at the ready, swung around the neighboring corner, as I joined the council. They were comparatively fresh, for all they had done was to lie in the shelter of houses, and pot at the windows in the fortalice. Mileff called for a list of casualties. We had lost two men killed, including the handsome young chief of the militia detachment, and two wounded. So far as we knew, two of the enemy were dead."There must be no more of this," said Mileff, decisively. “I cannot afford to waste good men on a nest of rats. They must be smoked out." He explained his plan. His detachment would form a covering force for Andrea's party, who would carry inflammable materials into the lower floor of the house. When a sufficient quantity had been collected, they would be set alight. After that, it would only be necessary to shoot any Turks who tried to escape. Without any unnecessary talk, the sub-chiefs ran to their detachments, and told off men for the work. Andrea's party broke into near-by yards, and seized all the lumber, hay, and straw they could find. One man discovered a large can of oil, which was received with joy. Fagots were made, and a dozen of us deployed along the street in positions which commanded the house windows.Finally, when all the fagots were ready, our fire was stopped completely.

“Almost immediately, the Bashi-bazouks ceased shooting. It was as if they realized that a new development might be expected, and had stopped firing to listen—to strain their ears, that they might detect their enemy's next purpose. There sounded the sighing murmur of the voivode's whistle, and Andrea's squad ran forward into the yard the rest of us, outside, kept a steady stream of lead pouring into the windows. Andrea's men were cheering as they ran; they had their rifles slung over their shoulders, and they meant to be in at the death. The Bashi-bazouks managed to fire back at us, but they were given no time to aim, and Andrea reached the house in safety. The fagots were hurled in through the doorway, and as each man threw down his load, he doubled back across the yard, out of the gate where Mileff and I were huddled, in the shelter of the posts. Andrea was the last to leave. He emptied the oil over the pile that bulged from the doorway; and stuck the lighted torch he carried into the mass. Then he, too, ran for the gate. A burst of cheering greeted him from the chetniks' line, and, as if in a frenzy of despair, the Bashi-bazouks redoubled their fire, the spurtsof flame squirting from the upper windows in never ceasing streams. “

Satisfaction Over Defeating and Killing the Bashi-Bazouks

killing a Turk

Arthur D. Howden-Smith wrote in “An Attack on the Bashi-Bazouks, Macedonia, 1907": Looking back, coldly, it seems a monstrous cruel thing to do—this roasting alive of half a dozen men It is difficult to believe that it could have happened in this so-called enlightened twentieth century. For some reason, it seems to smack more of the bigoted cruelty of the days of the Inquisition, or when a mere matter of kings' names was sufficient to cause the beheading of honest men. But, after all, it could not have been helped. It was the quickest and cheapest way to get rid of a nest of vermin that had been terrorizing the countryside,—thieves, murderers, and women-stealers, every one of them. They do not understand, and set squeamishness down as weakness. The flames gained rapidly. They leaped to the stables that had escaped the first blaze and licked them up, mounting the outer walls of the house, and gaining footholds through the windows. It was not many minutes before the whole building was a single vast pillar of flames that towered to the sky, making the village, and the hills surrounding it, loom blackly against the unnatural glare. And from this house of flames came a shrill screaming, such as words cannot hope to describe and such as once heard it is beyond the power of man to forget. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States,and Turkey, pp. 421-435]

“The chetniks leaned sternly on their rifles, watching the conflagration take its course, and the villagers, by this time certain of the identity of the marauders, stole from their homes to look also on the destruction of their oppressors.For months they had groaned beneath the exactions of the little band of arrogant, well-armed Bashi-bazouks, and yet, now when their deliverance had come, they could not exult. They could only look on, awesomely, at the dreadful doom that had been meted out by the "Men of the Night." In little knots they thronged the house-tops and the streets, watching the flames that swirled and roared, the women hugging their children to their breasts, and the men staring with a fixed concentration at the scene. As the front wall of the house fell in amid a shower of coals, Mileff's signal blew, and the chetniks hastened to him from their positions in the rough circle they had cast about the place, to prevent the possible escape of any of its inmates.

Several had bandaged arms or heads. One was carried by a couple of comrades on a rude litter. The villagers watched them with even greater awe than they had the burning fortalice. But the magic of the night was upon them, and they said no word. As silently as they came, the chetniks formed their line and departed through the dust of the road, the people who lined the way looking at them with curious drawn faces. A baby cried drearily, because it was tired, and a second wall fell in the house that had become the tomb of the Bashi-bazouks. On a crest the cheta halted for a minute, and I looked back at Osikovo, still showing red in the fire glare, and dotted with the groups of wonder-struck peasants. In the east, a beam of rosy light shot over the dark wall of the pines, and Mileff muttered "Heidi!" [forward] to the weary men who stumbled after him.”

Balkan Wars

states involved in the First Balkan War

Ottoman ruled ended in the Balkans after the Turks were ousted from Bulgaria, Serbia, Montenegro in the brutal First Balkan War in 1912. The Second Balkan War in 1913 was fought between Greece, Serbia and Bulgaria over the division of Macedonia. Before the wars, the power exerted over the Balkans by the Ottoman Empire was greatly reduced after a defeat by the Ottomans to Russia in 1877-1878. After thatnationalist and rebel movements were born in Macedonia and other Balkan Countries.

Four Balkan states defeated the Ottoman Empire in the first war; one of the four, Bulgaria, suffered defeat in the second war. The Ottoman Empire lost the bulk of its territory in Europe. Austria-Hungary, although not a combatant, became relatively weaker as a much enlarged Serbia pushed for union of the South Slavic peoples. The war set the stage for the Balkan crisis of 1914 and thus served as a "prelude to the First World War". [Source: Wikipedia +]

By the early 20th century, Bulgaria, Greece, Montenegro and Serbia had achieved independence from the Ottoman Empire, but large elements of their ethnic populations remained under Ottoman rule. In 1912 these countries formed the Balkan League. The First Balkan War had three main causes: 1) The Ottoman Empire was unable to reform itself, govern satisfactorily, or deal with the rising ethnic nationalism of its diverse peoples. 2) The Great Powers quarreled amongst themselves and failed to ensure that the Ottomans would carry out the needed reforms. This led the Balkan states to impose their own solution. 3) Most importantly, the Balkan League had been formed, and its members were confident that it could defeat the Turks. +

The Ottoman Empire lost all its European territories to the west of the River Maritsa as a result of the two Balkan Wars, which thus delineated present-day Turkey's western border. A large influx of Turks started to flee into the Ottoman heartland from the lost lands. By 1914, the remaining core region of the Ottoman Empire had experienced a population increase of around 2.5 million because of the flood of immigration from the Balkans. +

Citizens of Turkey regard the Balkan Wars as a major disaster (Balkan harbi faciası) in the nation's history. The unexpected fall and sudden relinquishing of Turkish-dominated European territories created a psycho-traumatic event amongst many Turks that is said[by whom?] to have triggered the ultimate collapse of the empire itself within five years. Nazım Pasha, Chief of Staff of the Ottoman Army, was held responsible for the failure[citation needed] and was assassinated on 23 January 1913 during the 1913 Ottoman coup d'état. +

First Balkan War

The First Balkan War began when the League member states attacked the Ottoman Empire on 8 October 1912 and ended eight months later with the signing of the Treaty of London on 30 May 1913. The Second Balkan War began on 16 June 1913. Both Serbia and Greece, utilizing the argument that the war had been prolonged, repudiated important particulars of the pre-war treaty and retained occupation of all the conquered districts in their possession, which were to be divided according to specific predefined boundaries. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Seeing the treaty as trampled, Bulgaria was dissatisfied over the division of the spoils in Macedonia (made in secret by its former allies, Serbia and Greece) and commenced military action against them. The more numerous combined Serbian and Greek armies repelled the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked into Bulgaria from the west and the south. Romania, having taken no part in the conflict, had intact armies to strike with, invaded Bulgaria from the north in violation of a peace treaty between the two states. The Ottoman Empire also attacked Bulgaria and advanced in Thrace regaining Adrianople. In the resulting Treaty of Bucharest, Bulgaria lost most of the territories it had gained in the First Balkan War in addition to being forced to cede the ex-Ottoman south-third of Dobroudja province to Romania. +

Alfred Lord Tennyson: Montenegro

Eva March Tappan wrote: “In the Middle Ages, Montenegro was under the control of Serbia; but when the battle of Kossovo laid Serbia at the mercy of the Turks, in 1389, Montenegro became independent; and independent it has remained. It is a country of warriors, who were well prepared to play their part in the late Balkan War.” [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, p. 420.

Alfred Lord Tennyson wrote in “Montenegro”:

They rose to where their sovereign eagle sails,

They kept their faith, their freedom, on the height,

Chaste, frugal, savage, arm'd by day and night

Against the Turk; whose inroad nowhere scales

Their headlong passes, but his footstep fails,

And red with blood the Crescent reels from fight

Before their dauntless hundreds, in prone flight

By thousands down the crags and thro' the vales.

O smallest among peoples! rough rock-throne

Of Freedom! warriors beating back the swarm

Of Turkish Islam for five hundred years,

Great Tsernogora! never since thine own

Black ridges drew the cloud and brake the storm

Has breathed a race of mightier mountaineers.

Siege of Adrianople, 1912

Adrianople is now known as Edirne, a town in present-day Turkey near the Bulgarian border. Eva March Tappan wrote: “In February, 1912, Bulgaria, Serbia, Greece, and Montenegro formed an alliance for the purpose of wresting from Turkey her European territory. War began in October. The Turks, fatally handicapped by the inefficiency and dim organization of their commissariat, were steadily driven back by the invading armies, and Scutari and Adrianople, their most important cities in Europe, were besieged. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 436-440]

moving in artillery for the Siege of Adrianople

Philip Gibbs wrote in “The Siege of Adrianople” (1912): “So the siege went on, tedious and interminable, and as often as possible I went out to the hills, dodging the vigilant officers, who had a quick eye for the red brassard of a correspondent, and riding or walking as far as possible from the main road until I had reached the last hill which looked down upon the city. From afar the turrets and roofs and domes and minarets of Adrianople appeared like a mirage through a haze of sunshine and a thin veil of mist. The sky was very clear above it. Only a few fleecy clouds rested above the horizon.

“But suddenly, as I watched one day, a new cloud appeared like a great ball of snow, which unfolded and spread out in curly feathers, and then, after a few moments, disappeared. It was the bursting of a great shell, and the report of it came with a crash of thunder which seemed to shake the hills. Two, three, four shells burst together like bubbles, and then there followed long, low rolls of thunderous sound like great drums beating a tattoo. The noise had a peculiar rhythm, like the Morse code, with long stroke and short, signaling death. It was made by the Bulgarian batteries on the hill-forts, and it was answered by the Turkish batteries from neighboring hills. Presently, as the wreaths of smoke from the guns faded into the atmosphere, I saw that tall, straight columns of smoke were rising from the city of Adrianople and did not die down. They rose steadily and spread out at the top, and flung great wisps of black murkiness across the sky. It was the smoke of buildings set on fire by the shells. Other towers of black smoke rose from valleys which dipped between hills. The Turkish shells, far-flung from their fortifications, crashed into little villages once under Turkish rule and now abandoned by all inhabitants. Soon there would be nothing left of them but blackened stumps and heaps of ash.As I stood watching one day I saw two scenes in this grim drama which made my pulses beat with a great excitement.

Air Attacks During the Siege of Adrianople, 1912

Philip Gibbs wrote in “The Siege of Adrianople” (1912): A great bird flew across the sky towards the city, and as it flew it sang a droning song like the buzzing of an enormous bee. It was a monoplane, flown by a Bulgarian aviator, who had volunteered to reconnoiter the Turkish defenses. It disappeared swiftly into the smoke-wrack, and for some time I listened intently to a furious fusillade which seemed to meet this winged spy. After half an hour the aeroplane came back, flying swiftly away from the shot and shell which pursued it from the low-lying hills. Its wings were pierced, so that one could see the sky through them, but it flew steadily from the chase of death, and I heard its rhythmic heart-beat overhead. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 436-440]

Siege of Adrianople

“Its escape was certain now. It had mocked at the pursuit of the shells, and the loud beat of its engine above me was a song of triumph. I watched it disappear again—to safety. So it seemed; but death has many ways of capture, and when I came back to Mustafa Pasha that day I heard that the unfortunate aviator, after his escape from the guns, had fallen from a great height within sight of home, and that the hero's body lay smashed to pieces in the wreckage of his machine.Then on another day I saw another drama in the air.

“While my eyes watched the smoke-clouds from the siege-guns something twinkled and glittered to the left of the four tall minarets of the great mosque of Adrianople. It was the smooth silk of an airship which caught the rays of the sun; this cigar-shaped craft rose slowly and steadily to a fair height, though I think it was tethered at one end. It rose above peaceful ground into a great tranquillity, which lasted about ten minutes. Then suddenly there was a terrific clap of thunder and a shell burst to the left of the airship. I gave a great cry. It seemed to me that the frail craft had burst and disappeared into nothingness. But a few seconds later, when the smoke was wafted away, I saw the airship still poised steadily above the earth, untouched by that death machine. A second shell was flung skywards, far to the right; and for an hour I watched shells rise continually round that airship, trying to tear it down from its high observation, but never striking it. I do not know the names of the men who piloted that ship, but, whoever they were, they may boast of a courage which kept them at their post in the sky—amid that storm of shells.It was at night that the bombardment of Adrianople reached the heights of a most infernal beauty. Then the sky quivered with flashes of light, and tongues of flame leaped out from the hillsides, and fire-balls danced between the stars.

Artillery Attacks During the Siege of Adrianople, 1912

Philip Gibbs wrote in “The Siege of Adrianople” (1912): “As I lay in bed after a day on the hills the noise of the bombardment chased sleep away, and every great gun shook the old Turkish farmhouse in which I lived as though heavy iron bedsteads were being dumped down upon the roof. Then there came a continued roll of great artillery. It was so loud and seemed so close that for a moment the wild idea came to me that the Turks had smashed their way out of the besieged city and that there was fighting in Mustafa Pasha. I rose and dressed hastily, lighted a lantern, and went out into the darkness. All around me was the barking and howling of dogs, hundreds of them, baying back an answer to the guns. I stumbled through quagmires of mud and pools of water until I came to the bridge of Mustafa overlooking the wide sweep of the Maritza. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art, (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 436-440]

“I passed on through the village, and past many lines of sentries and men encamped round fires outside the mosques. Then in the shadow of a doorway I stood still and watched the sky, upon which was written the signs of death still seeking victims, and destruction away in the city below the hills. There was no moon, but the sky was thickly strewn with stars, and it seemed as though some flight of fallen angels were raging in the heavens. I saw a great shell burst below Orion's belt, and the pointers of the Great Bear were cut across by a sword of flame. The Milky Way throbbed with intermittent flashes like sheet lightning, and the pathway of the stars was illumined by the ruddy glare of burning houses and smouldering villages. I had an irresistible desire to get closer to all this hellish beauty, to walk far across the hills to a place of vantage from which I had seen the bombardment by day. But when I raised my lantern and walked forward I was arrested by a Bulgarian officer—and this was the end of my night's vigil.As all the world knows now, the city of Adrianople did not fall before the armistice arranged between the allies and Turkey; and its garrison, which had maintained such an heroic defense, deserved the fullest honors.”

civilians drowned in a river during the Siege of Adrianople

Battle of Lule-Burgas

Battle of Kirk Kilisse was part of the First Balkan War between the armies of Bulgaria and the Ottoman Empire. It took place on 24 October 1912, when the Bulgarian army defeated an Ottoman army in Eastern Thrace. The initial clashes were around several villages to the north of the town. The Bulgarian attacks were irresistible and the Ottoman forces were forced to retreat. On 10 October the Ottoman army threatened to split 1st and 3rd Bulgarian armies but it was quickly stopped by charge by 1st Sofian and 2nd Preslav brigades. After bloody fights along the whole town the Ottomans began to pull back and on the next morning Kırk Kilise (Lozengrad) was in Bulgarian rule.

After the capture of Kirk-Kilisse, the Bulgarians, pushed on to cut off the retreat of the Turks. Part of the Turkish forces were withdrawn to Lule-Burgas, and here a fierce battle took place, The Battle of Lule Burgas took place from October 28 to November 2 1912. The outnumbered Bulgarian forces made the Ottomans retreat to Çatalca line, 30 kilometers from the Ottoman capital Constantinople. In terms of forces engaged it was the largest battle fought in Europe between the end of the Franco-Prussian War and the beginning of the First World War. At the the close of the battle the Turks were forced to make the retreat which is here described.

Bernard Grant wrote in “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas” (1912): “I now come to the days of October 29 and 30. Glorious weather continued, and tempted all of us to the open country, away from this filthy little village, where we were penned up like sheep. From afar I heard the music of the guns. It came in continuous shocks of sound, the crash of great artillery bursting out repeatedly into a terrific cannonade. It was obviously the noise of something greater than a skirmish of outposts or a fight between small bodies of men.While the war correspondents were cooking food in their stewing-pots a big battle was in progress, deciding the fate of nations and ending the lives of many human beings. That thunder of guns made my pulses beat, throbbed into my brain. I could not rest inactive and in ignorance of the awful business that was being done beyond the hills. Ignoring the orders to remain in the village, I rode out towards the guns. Although I did not know it at the time, as we were utterly without information, I was riding towards the battle of Lule-Burgas, which destroyed the flower of the Turkish army and opened the way of the Bulgarians to Constantinople. [Source: Bernard Grant “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas,” 1912, Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 441-450]

“Of the actual battle itself I am unable to speak as an eyewitness. Indeed, there was no mortal eye who could see more than a small part of it, as it covered a front of something like fifty miles; and even to the commanders of the army corps engaged, it was a wild and terrible confusion of great forces hurling themselves upon other great bodies of men, sometimes pressing them back, sometimes retiring, swept by a terrific fire, losing immense numbers of men, and uncertain of the damage they were inflicting upon the opposing troops. Only from those who took part in it have I been able to gather some of the grim details of that great tragedy to the Turks.

Battle of Lule-Burgas

“Certain facts stand out in all their accounts. The Turkish artillery was overmastered from the first. The Bulgarian guns were in greater numbers and better served, and they had an inexhaustible supply of ammunition. Not so the Turks. In consternation, in rage, in despair, the Turkish artillery officers saw their ammunition dwindling and giving out at a time when they needed it most: when the enemy's shells were bursting continuously upon their positions, when the enemy's infantry were exposing themselves on the ridges, and when the Bulgarian soldiers made wild rushes, advancing from point to point, in spite of their heavy losses in dead and wounded. There were Turkish officers and soldiers who stood with folded arms by the limber of guns that could no longer return the enemy's fire, until to a man they were wiped out by the scattered shells. The frantic messages carried to the commander-in-chief notifying him of this lack of ammunition passed unheeded, because the supply was exhausted.”

Fighting Against the Turks at Lule-Burgas, 1912

Bernard Grant wrote in “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas” (1912): “Abdullah Pasha was a sad man that day, when from one of the heights he looked down upon his scattered army corps and saw how gradually their fire was silenced. Now on his right wing and his left his legions were pressed back until they wavered and broke. And now, with an overwhelming power and irresistible spirit of attack, the Bulgarians cut the railway line, scattered his squadrons of cavalry, broke through his various units, and bore down upon his rear-guard holding the town of Lule-Burgas. I do not believe the Turkish soldiers were guilty of cowardice during those hours of battle. It was only afterwards, when the fighting was finished and the retreat began, that panic made cowards of all of them and seemed to paralyze them. [Source: Bernard Grant “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas,” 1912, Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 441-450]

“But from all that I have heard the Turkish soldiers in the mass behaved as bravely during the battle as all the traditions of their fighting spirit have led us to believe. They fought resolutely and doggedly, although, as I know now, they had gone into the battle hungry and were starving at the end of it. They died in sufficient numbers, God knows, to prove their valor. They died in heaps. Many of the battalions were almost annihilated, and the greatest honor is due to the men of the Second Corps, who, after they had been beaten back again and again, after the battle had really been lost irretrievably by the failure of Mukhtar Pasha to repress the general attack of the Bulgarians with his Third Army Corps, which had come up from the direction of Viza, re-formed themselves and marched to an almost certain death. For a little while they held their own, but the Bulgarians were now in an impregnable position on the heights, and in such places of vantage for their artillery that they could concentrate their fire in a really terrific manner.

“The men of the Second Corps found themselves in a zone of bursting shells, and in the face of a withering rifle fire which swept upon them like a hailstorm. A great cry broke from the ranks of the living, in which already there were great gaps, as the dead and wounded fell in all directions. The ranks were broken. It was only a rabble of terror-stricken men, running away from that hunting-ground of death, who came back beyond the reach of the Bulgarian bullets. The town of Lule-Burgas was already in the hands of the enemy. And in the great field of battle, extending over the wild countryside for many miles, divisions, regiments, and battalions were scattered and shattered, no longer disciplined bodies of men, but swarms of individuals, each seeking a way to save his own life, each taking to flight like a hunted animal, each bewildered and dazed by the tragic confusion in which he staggered forward.”

after the Battle of Lule-Burgas

Retreating Soldiers and Refugees

Bernard Grant wrote in “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas” (1912): This is a connected account of what happened. But in war events are not seen connectedly, but piecemeal, confusedly, and without any apparent coherence, by those who are units in a great scheme of fate. So, looking back upon those days, it seems to me that I lived in a muddling nightmare, when one experience merged into another, and when one scene changed to another in a fantastic and disorderly way. I first came in touch with bodies of retreating soldiers when, in my ride out from the village of Chorlu, I crossed the railway line and went on towards the guns. Those men were in straggling groups or walking singly. They were the first fugitives, the first signs, on this day of Tuesday, 29th, that the battle which was raging with increasing fury was not going well for the Turks. The men were coming away from the fight weary, dejected, hopeless. They had no idea as to the direction in which they wanted to go. They wandered along aimlessly, some this way, some that, all of them silent and sullen, as though brooding over the things they had seen and suffered, and as though resentful of the fate that had befallen them. [Source: Bernard Grant “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas,” 1912, Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 441-450]

“I did not grasp the full significance of these wandering soldiers. I thought they were just faint-hearted fellows who had deserted from their battalions. Soon I saw the real truth. The pale dawn came grayly across the plain, and the shadows of night crept away, and in the hush of the early hour men were silent, wondering what would be the fortune of war that day. So came the break of day on October 31st, a date which now belongs to history, remembered with bitterness by the Turks and with triumph by the Bulgarians. Before the sun had dispelled the white, hard frost on the grass there came to our ears once more the thunder of the guns, which had stopped at dark on the night before. We made a hasty breakfast, eager to get close to the battle, not only for professional reasons, but because no man may withstand the thrill which comes when men are fighting. But our hopes were dashed to the ground, and we were thrown into consternation when Major Waffsy came to us and ordered an instant and hurried retreat. We were disposed to rebel, to protest against this order, which seemed ignominious, and absurd, and unreasonable. But very soon we saw that Waffsy Bey had reason on his side and that things were very serious.

“Thousands of Turks were making their way in great disorder in the direction of Chorlu. They were literally running from the distant guns. They were like great flocks of sheep scared by the wolf, and stumbling forward. Men fell as they ran, stumbling and staggering over the boulders and in the ruts. They seemed to be pursued by an invisible terror, so that they did not dare to stop, except to regain breath to amble forward with drooping heads. They had no shame in this flight. These tall fellows of fine physique, except for their leanness and starvation looks, ran like whipped dogs, with eyes that glinted with the light of a great fear. It was a distressing and painful sight. Major Waffsy seemed in just as much hurry. The sight of these fugitive soldiers seemed to shake his nerves terribly, and his face was very white and strained. I pitied the man, for he was a patriotic Turk and a courteous gentleman, although sometimes we hated him because he kept us so strictly in hand. Now he started back on the line of the retreat with part of his charge, who seemed to think that this time he would be a valuable companion; but none of the English went with him. We had decided to give him the slip. So we tarried over our preparations and deliberately lengthened the time of our packing, and found many difficulties in the way of an early start.

troops retreating from Lule Burgas accross the bridge at Karisdiran

“Major Waffsy set off without us, not suspecting our ruse, and when he was well out of harm's way we proceeded on our own line of route, which was forward to the battle-field.I made my way to the river and there saw an astounding sight of panic in its most complete and furious form. It was, indeed, the very spirit of panic which head taken possession of the soldiers whom I now met on this spot. Never before had I seen men so mad with fear. I hope that never again shall I see a great mass of humanity so lost to all reason, so impelled by the one terrible instinct of flight. The bridge was absolutely blocked with retreating soldiers. It was a great stone bridge, with many archways and a broad roadway, with one part of its parapet broken; but, broad as it was, it was not wide enough to contain the rabble ranks which pressed across from the farther bank. They struggled forward, trampling upon each other's heels, pushing and jostling like a crowd escaping through a narrow exit from a theater fire.Most of the men were on foot, some still hugging their rifles, and using them to prod on their foremost fellows, but some of them were unarmed. They bent their heads down, drooped as though their strength was fast failing, breathed hard and panted like beasts hunted after a long chase, and came shambling across the bridge as though on one side there was the peril of death and on the other side safety. The horsemen in the crowdùrugged men swathed in drab cloths like mummies taken from their cases, on lean-ribbed and wretched horses—would not wait for the procession across the bridge, but, spurred on by panic, dashed into the water and forded their way across. All seemed quite regardless of the fact that the Bulgars were several miles away, and that the difference of a few miles would not count in the gap between life and death.I almost expected to see a squadron of the Bulgarian cavalry charging down upon this mass of men, so abject was their terror.

“But the plain behind them showed no sign of an enemy. No guns played upon the fugitives. Instead came a force of Turkish cavalry with drawn swords, galloping hard and rounding up the fugitives. Many officers did their best to stem the tide of panic, and beat the men back with the flats of their swords, and threatened them with their revolvers, shouting, and cursing, and imploring them. But all the effect they had was to check a few of the men, who waited until the officers were out of sight, and then pressed forward again. With a young British officer who was out to see some fighting,

Fighting and Death at Lule-Burgas

Bernard Grant wrote in “The Flight of the Turks from Lule-Burgas” (1912): I turned again towards the town of Lule-Burgas, where a great fight was now taking place, and rode against the incoming stream of wounded and retreating soldiers.They seemed to come on in living waves round my horse, and I looked down upon their bent figures, and saw their lines staggering below me, and men dropping on all sides. I saw the final but fruitless struggle of many of them as they tried to keep their feet, and then fell. I saw the pain which twisted the faces of those who were grievously wounded. I saw the last rigors of men as death came upon them.

Second Balkan War: this war was a conflict which broke out when Bulgaria, dissatisfied with its share of the spoils of the First Balkan War, attacked its former allies, Serbia and Greece, on 16 / 29 June 1913. Serbian and Greek armies repulsed the Bulgarian offensive and counter-attacked, entering Bulgaria.

When we got nearer to the roaring guns, breaking out into great volleys which seemed to shake the earth, and to set the air throbbing, the retreat was being carried out in a more orderly fashion. Men were marching in rank with their rifles slung across their shoulders, and with officers pacing alongside. Those who had broken the ranks were stopped, and unless wounded were compelled to come into the ranks again. I saw many men being chased with whips and swords, while non-commissioned officers were set apart to cut off the stragglers. They were spent with fatigue, and suffering from hunger and thirst, and despondency was written on every face, but at least it was a relief to see an orderly formation and a body of men who had not lost all courage and self-respect. Evidently the best of the army was at the front. [Source: Eva March Tappan, ed., “The World's Story: A History of the World in Story, Song and Art,” (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1914), Vol. VI: Russia, Austria-Hungary, The Balkan States, and Turkey, pp. 441-450]

“As my companion and I were short of food and darkness was coming on, we decided to turn, especially as the fight could not last until the next morning. At dusk we reached the village of Karistaran and met Angus Hamilton and H. Baldwin, and together set out for a night ride to Chorlu.This was far from pleasant. The army was in full retreat, and the roads and bridges were thronged, so that it was impossible to push one's way through the tramping men who, of course, would not open up for us, and whose rifles were like a moving hedge in front of us. It was also difficult to ride at the side of the roads, on account of the exhausted and dying soldiers who lay about in the mud while their comrades passed. This was a sickening thing, and I had a sensation of horror every time my horse halted before one of those prone bodies, or when I had to pull it out of the way of one of them. Another difficulty that worried me was the absence of an interpreter. We should not know if we were challenged, and could not answer if we knew, so that we were in real danger. As a measure of precaution we rode as near as possible together in a group of four, hoping, in the darkness, to be taken for a patrol. If we had been recognized as foreigners, we might have lost our horses; for these Turks, wounded or exhausted, would have coveted our mounts, for which they had a really desperate need. Reading this in cold blood people may accuse us of selfishness. It would have been heroic, they might think, to dismount and, in Christian charity, yield up our horses to suffering men. But that idea would have seemed fantastic had it occurred to us for a moment. We had our duty to perform to our papers, and what, after all, would four horses have meant among so many? Such a sacrifice would merely have led to our own undoing.

“Never shall I forget that ride in the dark night to Chorlu, the vague forms of the retreating army passing with us and around us like an army of ghosts, the strange, confused noise of stumbling feet, of voices crying to each other, of occasional groans, of clanking arms, of chinking bits and bridles, the sense of terror that seemed to walk with this army in flight, the acuteness of our own senses, highly strung, apprehensive of unknown dangers, oppressed by the gloom of this mass of tragic humanity. At last we reached Chorlu in the early hours of the morning, utterly tired out in body and spirit and quite famished, as we had only had a few biscuits since our scanty breakfast on the previous day.”

Bulgarian territory after the end of the Balkan wars in 1913. Annexed territory from the Ottoman Empire in gold, Territory ceded to Romania in dark purple

Image Sources: Wikimedia, Commons

Text Sources: Internet Islamic History Sourcebook: sourcebooks.fordham.edu “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “ Arab News, Jeddah; “Islam, a Short History “ by Karen Armstrong; “A History of the Arab Peoples” by Albert Hourani (Faber and Faber, 1991); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures” edited by David Levinson (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1994); “Encyclopedia of the World’s Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Geographic, BBC, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The Guardian, BBC, Al Jazeera, Times of London, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, Associated Press, AFP, Lonely Planet Guides, Library of Congress, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated September 2018