MONGOL ART

Ilkhanid silk circular

The Mongols for the most part did not produce much art let alone art that is preserved today. They were a nomadic people who carried their possessions on horseback and kept them in tents. They were not known for building grand palaces and filling them with works of art and treasures. However in places where they did settle down— namely in China. Persia and the Middle East— artists and craftsmen hired by Mongol leaders did produce some great work or works. Some of the greatest works were produced by the Ilkanids and the Yuan Dynasty Chinese. For the most part the works were created by people under the Mongols not the Mongols themselves.

According to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: “The Mongols’ promotion of pan-Asian trade, their avid taste for luxury goods, and their practice of relocating artists combined to produce an unprecedented cross-fertilization of artistic ideas throughout Eurasia.” In some parts of the Mongol Empire, the Mongol era “was a period of brilliant cultural flowering as the Mongol masters sought to govern their disparate empire, and in the process they sponsored the creation of a remarkable new visual language. By uniting eastern and western Asia for over a century, the Mongols produced a unique occasion for cultural exchange,” producing “lively manuscript illustrations, opulent decorative arts, and splendid architectural elements.” [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition]

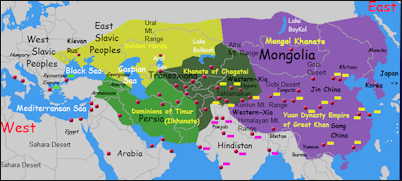

The vast Mongol empire was divided among four dynasties: the Ilkhanids in the Middle East and Iran, the Golden Horde in southern Russia, the Chaghatay in central Asia, and the Yuan in China and Mongolia

Websites and Resources: Mongols and Horsemen of the Steppe:

Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

The Mongol Empire web.archive.org/web ;

The Mongols in World History afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ;

William of Rubruck's Account of the Mongols washington.edu/silkroad/texts ;

Mongol invasion of Rus (pictures) web.archive.org/web ;

Encyclopædia Britannica article britannica.com ;

Mongol Archives historyonthenet.com ; “The Horse, the Wheel and Language, How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes shaped the Modern World", David W Anthony, 2007 archive.org/details/horsewheelandlanguage ; The Scythians - Silk Road Foundation silkroadfoundation.org ;

Scythians iranicaonline.org ;

Encyclopaedia Britannica article on the Huns britannica.com ; Wikipedia article on Eurasian nomads Wikipedia

Books: Amitai-Preiss, Reuven, and David O. Morgan, eds. The Mongol Empire and Its Legacy. Leiden: Brill, 1999; Carboni, Stefano, and Komaroff, Linda, eds. The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353. Exhibition catalogue.. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002; Rossabi, Morris "Genghis Khan." In The Encyclopedia of Asian History, vol. 1, pp. 496–98.. New York: Scribner, 1988;

Pax Mongolia and Cultural Exchanges

Mongol empire in 1294

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: “The Mongols promoted inter-state relations through the so-called "Pax Mongolica" — the Mongolian Peace. Having conquered an enormous territory in Asia, the Mongols were able to guarantee the security and safety of travelers. There were some conflicts among the various Mongol Khanates, but recognition that trade and travel were important for all the Mongol domains meant that traders were generally not in danger during the 100 years or so of Mongol domination and rule over Eurasia. [Source: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu/mongols ]

“The Mongols' favorable attitude toward artisans benefited the Mongols themselves, and also ultimately facilitated international contact and cultural exchange. The Mongols recruited artisans from all over the known world to travel to their domains in China and Persia. Three separate weaving communities, for example, were moved from Central Asia and Persia to China because they produced a specific kind of textile — a cloth of gold — which the Mongols cherished.

“Apparently some Chinese painters — or perhaps their pattern books — were sent to Persia, where they had a tremendous impact on the development of Persian miniature paintings. The dragon and phoenix motifs from China first appear in Persian art during the Mongol era. The representation of clouds, trees, and landscapes in Persian painting also owes a great deal to Chinese art — all due to the cultural transmission supported by the Mongols.”

Mongol Symbols in Chinese Art

page from the Great Mongol Shahnama

Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “ In the creation of luxury textiles and objects for the Mongol elite, Chinese artists developed a visual language that was an effective means of establishing their rule and consolidating their presence throughout the vast empire. A number of motifs that were part of the existing artistic repertoire were adopted as imperial symbols of power and dominance—the dragon and the phoenix, for example, two mythical beasts that integrated the ideas of cosmic force, earthly strength, superior wisdom, and eternal life. The Mongol versions of the creatures are the highly decorative sinuous dragon with legs, horns, and beard and the large bird with a spectacular feathered tail floating in the air. In Iran, these motifs were often paired and became so popular with the Ilkhanids that they eventually lost their original meaning, becoming part of the common artistic repertoire in the first half of the fourteenth century. [Source: Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Other motifs of this period that were familiar throughout the Asian continent are the peony, the lotus flower, and the lyrical image of the recumbent deer, or djeiran, gazing at the moon. The flowers, often seen in combination and viewed from both the side and top, provided ideal patterns for textiles and for filling dense backgrounds on all kinds of portable objects. The djeiran became widespread in the decorative arts because of the well-established association of similar quadrupeds with hunting scenes."^/

“For the semi-nomadic Mongols, portable textiles and clothing were the best means of demonstrating their acquired wealth and power, so it is reasonable to assume that the main mode of transmission of motifs such as the dragon and peony was through luxury textiles. The most prominent clothing accessories were belts of precious metal (gold belt plaques, The Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art). Many of the textiles illustrated here prove transmission from east to west, yet in some instances, exemplified by the Chinese silk with addorsed griffins (cloth of gold: winged lions and griffins, The Cleveland Museum of Art), the origin of the image is clearly Central or western Asia. The Mongol period is unique in art history because it permitted the cross-fertilization of artistic motifs via the movement of craftsmen and artists throughout a politically unified continent."^/

Ilkhanid Empire

According to the Los Angeles County Museum of Art: “By the mid-thirteenth century the Islamic lands beyond the Oxus River, which Genghis Khan’s forces had subdued earlier in the century, had slipped from Mongol control. Accordingly, the Great Khan (Genghis’s grandson) sent his brother Hülegü to consolidate and regain control of western Asia. Between 1256 and 1260 Hülegü conquered an immense territory including western Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, the Caucasus, and eastern Anatolia, which he now ruled on behalf of the Great Khan, assuming the title Il-Khan—meaning subordinate or lesser Khan.[Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

phoenix on an Ilkhanid tile

The Ilkhanid empire was one of three vast principalities nominally under the authority of the Great Khan, who ruled first from Mongolia and, later, China. Of the three, which also included the Golden Horde in southern Russia and the Chaghatay in central Asia, the Ilkhanids maintained the closest ties to China. However, after the death of Kublai Khan in 1294, the formal relationship between the Ilkhanids and the Great Khan or Yuan emperor was less strictly observed. The Ilkhanids’ adoption of Islam as their official state religion in 1295 must also have created a religious gulf with their Mongol cousins in China who had embraced Buddhism.^\^

“Even as the formal alliance between Iran and China lessened, cultural exchange flourished as luxury wares and artists traveled freely across the empire—a process that energized Iranian art with novel forms, meanings, and motifs that were further disseminated throughout the Islamic world. With the Ilkhanids’ conversion to Islam and acculturation to Persian customs and traditions came a remarkable patronage of arts and letters, encompassing written histories, sumptuously illustrated manuscripts, and brilliantly decorated architectural monuments.” ^|^

Ilkhan-Mongol Culture

Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: ““After their rapid gain of power in the Muslim world, the Mongol Ilkhanids nominally reported to the Great Khan of the Yuan dynasty in China, and in the process imported Chinese models to better define their tastes. However, the new rulers were greatly impressed by the long-established traditions of Iran, with its prosperous urban centers and thriving economy, and they quickly assimilated the local culture.The Mongol influence on Iranian and Islamic culture gave birth to an extraordinary period in Islamic art that combined well-established traditions with the new visual language transmitted from eastern Asia." [Source: Department of Education,The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Based on original work by Linda Komaroff metmuseum.org \^/]

Ilkhanid ceramic

“After Ghazan's conversion, an aggressive program of construction and decoration of mosques was undertaken, while tolerance toward Shici Islam and Sufism promoted the building of tombs and shrines devoted to Sufi saints. The best Iranian craftsmen produced mosque furniture and furnishings. Large-scale luxurious Qur'an manuscripts were commissioned for religious institutions. Ilkhanid manuscript illustrations provide rare examples of representations of the prophet Muhammad and his companions, probably influenced by the circulation of Christian, especially Armenian, illustrated gospels and by the eclectic approach to religion in Iran at the time. \^/

Art and Architecture of the Ilkhanid Period (1256–1353)

Arguably, the most impressive art produced by the Mongols was made by the Ilkhanids in Iran. Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: The Mongol rulers in Iran “were greatly impressed by the long-established traditions of Iran, with its prosperous urban centers and thriving economy, and they quickly assimilated the local culture.The Mongol influence on Iranian and Islamic culture gave birth to an extraordinary period in Islamic art that combined well-established traditions with the new visual language transmitted from eastern Asia Following the conversion to Islam of the Il-Khan Ghazan (r. 1295–1304) in 1295 and the establishment of his active cultural policy in support of his new religion, Islamic art flourished once again. East Asian elements absorbed into the existing Perso-Islamic repertoire created a new artistic vocabulary, one that was emulated from Anatolia to India, profoundly affecting artistic production. [Source: Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, Department of Islamic Art, Based on original work by Linda Komaroff metmuseum.org \^/]

Emir Saltuk tomb in Erzerum Turkey

“During the Ilkhanid period, the decorative arts—textiles, pottery, metalwork, jewelry, and manuscript illumination and illustration—continued along and further developed established lines. The arts of the book, however, including illuminated and illustrated manuscripts of religious and secular texts, became a major focus of artistic production. Baghdad became an important center once again. In illustration, new ideas and motifs were introduced into the repertoire of the Muslim artist, including an altered and more Chinese depiction of pictorial space, as well as motifs such as lotuses and peonies, cloud bands, and dragons and phoenixes. Popular subjects, also sponsored by the court, included well-known stories such as the Shahnama (Book of Kings), the famous Persian epic. Furthermore, the widespread use of paper and textiles also enabled new designs to be readily transferred from one medium to another. \^/

“Along with their renown in the arts, the Ilkhanids were also great builders. The lavishly decorated Ilkhanid summer palace at Takht-i Sulayman (ca. 1275), a site with pre-Islamic Iranian resonances, is an important example of secular architecture. The outstanding Tomb of Uljaytu (built 1307–13; r. 1304–16) in Sultaniyya, however, is the architectural masterpiece of the period. Following their conversion to Islam, the Ilkhanids built numerous mosques and Sufi shrines in cities across Iran such as Ardabil, Isfahan, Natanz, Tabriz, Varamin, and Yazd (ca. 1300–1350). After the death of the last Ilkhanid ruler of the united dynasty in 1335, the empire disintegrated and a number of local dynasties came to power in Iraq and Iran, each emulating the style set by the Ilkhanids. \^/

See Separate Article ILKHANID (MUSLIM MONGOL) ART factsanddetails.com

Books: Carboni, Stefano, and Komaroff, Linda, eds. The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256–1353. Exhibition catalogue. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art, 2002; Grube, Ernst J. Persian Painting in the Fourteenth Century: A Research Report. Naples: Istituto Orientale di Napoli, 1978; Hillenbrand, Robert, ed. Persian Painting from the Mongols to the Qajars: Studies in Honour of Basil W. Robinson. London: I. B. Tauris, 2000; Raby, Julian, and Teresa Fitzherbert, eds. The Court of the Il-Khans, 1290–1340. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996; Safadi, Yasin Hamid. Islamic Calligraphy. New York: Thames & Hudson, 1987; Soudavar, Abolala. Art of the Persian Courts: Selections from the Art and History Trust Collection. New York: Rizzoli, 1992; Wilber, Donald N. The Architecture of Islamic Iran: The Il Khanid Period. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1955.

Pen Case with Hadith Inscription, 14th century, Ilkhanid period, probably western Iran, incised brass with silver and gold inlay

Courtly Art of the Ilkhanids

Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art wrote: “Members of the Ilkhanid court wore expensive clothes and accessories, whether they were traveling in luxurious tents or settling in one of their palaces for a while. They also surrounded themselves with opulent functional objects, from wine containers to serving trays, storage jars (56.185.3) to food bowls, lighting devices to wash basins. Some of these items may have been part of the traveling effects of the court, but the majority can be regarded as palace furnishings that were commissioned from the finest craftsmen. Little is known about direct sponsorship and court workshops because few extant objects include inscriptions with dedications or signatures. Nevertheless, the elaborate vessels inlaid with silver and gold and the lavish gilded blue-glazed lajvardina ceramics must have been a familiar sight for the ruler and his entourage and for the most affluent people in Ilkhanid Iran and Iraq. Lajvardina (from the Persian lajvard, or lapis lazuli) tiles, painted in white, black, and red enamels and gold over a monochrome dark blue or turquoise glaze, were often used as well. The lajvardina technique seems to have been a specialty of Iranian potters during the Ilkhanid period alone and was abandoned after their rule. [Source: Stefano Carboni and Qamar Adamjee, Department of Islamic Art, Metropolitan Museum of Art metmuseum.org \^/]

“Inlaid metalwork was highly prized and costly. The gold and silver inlays (91.1.521) that were gently hammered in the indentations carved in the bronze or brass surface have mostly disappeared, but it is still possible to appreciate the technical and artistic skills of the craftsmen who found inspiration in the new visual language brought by the Mongols. The best artists from Mosul in northern Iraq and Shiraz in southern Iran—two famous centers for metalwork—probably moved to the capital, Tabriz, to work for the court. \^/

“Luxury objects, jewelry, and clothing are often depicted in manuscript illustrations from the period, providing evidence of their existence and actual use at the court. The gold necklace (1989.87a-l) and a similar piece of jewelry illustrated in a page of the Great Mongol Shahnama are good examples of the correlation between the arts of the book and the decorative arts." \^/

Examples of Ilkhanid Court Art

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Candlestick, Sa'd ibn 'Abd Allah, Iran (Fars province), 1343-53, Brass, inlaid with silver and gold: “This remarkable candlestick was made for Abu Ishaq (reigned 1343-53), a ruler of the Injuid dynasty that controlled the southern Iranian province of Fars. It is noteworthy not only for its intricate, highly accomplished craftsmanship but also for the large, elaborate enthronement scenes encircling its base. At the base of the socket is a diminutive inscription providing other important information. It reads: "made by the feeble slave Sa'd ibn 'Abd Allah." This piece belongs to the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, Qatar. [Source: “The Legacy of Genghis Khan: Courtly Art and Culture in Western Asia, 1256-1353", Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 2003 exhibition ^\^]

“Encircling the base of this candlestick are four large enthronement scenes enclosed by medallions. Two of the scenes depict the ruler seated on a throne supported by lions and attended by members of his entourage. In one, he wears an elaborate Mongol headdress composed of rounded owl feathers and other, spikier plumage—probably eagle feathers. A third medallion shows a ruler and his consort sharing a platformlike throne. The consort wears the conical headdress reserved for Mongol noblewomen and known as a bughtaq. In the fourth medallion the consort, again wearing the bughtaq, is depicted alone on her throne., Arabic inscriptions set in cartouches on the base are especially significant as they give the name and titles of a member of the Injuid dynasty, Abu Ishaq (r.1343-53), who succeeded his father, Mahmud Shah, as ruler of the Fars.^\^

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Bowl with Four Phoenixes, Iran, 14th century, Fritware, underglaze painted: “This bowl belongs to a general category of Persian ceramics known as Sultanabad ware, after the western Iranian city (between Hamadan and Isfahan) [map] where many similar objects were found, although there is no proof that any of them were actually made there. The phoenix motif, in which the mythical birds are depicted in pairs or groups of three or four (here), typically arranged in the form of a revolving design emphasized the birds’ long, curving tail feathers, may also represent a Chinese import. ^\^

Other courtly object include: 1) a Tapestry Roundel, Iraq or Iran, first half of the 14th century, Tapestry weave, silk, gold thread wrapped around a cotton core; 2) Enthronement Scene, Iran (possibly Tabriz), early 14th century, Ink, colors, and gold on paper. ^\^

Golden Horde Art

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Cup with Fish-Shaped Handles, Golden Horde (Southern Russia), late 13th–14th century, Gold sheet, handles worked in repoussé and engraved: “ This spectacular gold cup was excavated at the site of New Saray (Saray al-Jadid) along the Volga River. New Saray was the second capital of the Golden Horde, the branch of the Mongol dynasty whose empire encompassed parts of the Caucasus, the Crimea, Siberia, and the vast steppe region north of the Caspian Sea.” This piece is now at the State Hermitage Museum, Saint Petersburg.

Los Angeles County Museum of Art description of Three Belt Plaques, Southern Russia or Central Asia, 13th century, Gold, repoussé, chased and engraved, granulation: “The exchange of belts and horses was evidently one means of commemorating alliances among the peoples of the Mongolian steppes. These three gold ornaments and the silver plaque all bear images of deer set within dense vegetation, a common decorative theme in the art of the Mongol empire. The motif was possibly introduced through contact with the art or artists of the Chinese Jin dynasty (1115–1234) when it was a standard decoration among officers in the emperor’s entourage. This piece is in the Nasser D. Khalili Collection of Islamic Art, London.

Metropolitan Museum of Art description of Tympanum with a Horse and Rider, second half 14th century, Caucasus, probably Kubachi, Dagestan, Stone; carved, with traces of paint (height: 73 centimeters; width; 129.5 centimeters; depth: 10.2 centimeters): “The vegetal decoration surrounding the central figure resembles that found on fourteenth- and fifteenth-century tombstones of the town of Kubachi, presently in the republic of Daghestan in the Caucasus. This attribution is supported by the "cloud" collar that covers the rider's chest, which became fashionable after the arrival of the Mongols in the area and was popular in the fifteenth century. The horseman represents a traditional image of a Central Asian nomadic archer, symbolic of the Mongol roots of the Golden Horde (1227–1502). In the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, between the Ilkhanid and the Timurid periods, this dynasty ruled over a large area in Russia, including the province of Daghestan on the north shore of the Caspian Sea. The horseman and his mount provide valuable information about costume and trappings in the Caucasus at this time. A short, tight-fitting short-sleeved tunic is worn over another garment. Tight-fitting high boots, a belt, and a hood reaching to the neck complete the costume. A leather pouch hangs from the belt, as does a quiver of typically Turkic type. [Source: Metropolitan Museum of Art \^/]

“This tympanum was once assembled on the front wall of the so-called House of Ahmed and Ibrahim at Kubachi, an important center under the control of the Golden Horde, which extended from the Lower Volga to the Caucasus on the northwestern shores of the Caspian Sea. It is not clear if the house was destroyed at the beginning of the twentieth century. The building that this object decorated must have been of a secular nature, perhaps the country house of a prince of the Golden Horde.” \=/

Mongol Literature

History had traditionally been kept alive by the Mongols through oral epics, performed by nomadic bards, until writing was introduced in the Genghis Khan era in the 12th century. Because the Mongol Empire was so vast the Mongols were written about in many languages by numerous chroniclers of divergent conquered societies, who provided a wide range of perspectives, myths, and legends. Much of what has been written about the Mongols was produced by people who came in contact with the Mongols—often enemies or hostile neighbors of the Mongols, who generally did not have nice things to say and were less than objective—not the Mongols themselves. Because many foreign accounts are about the Mongol invasions and were written by the conquered, the Mongols often are described in unfavorable terms, as bloodthirsty barbarians who kept their subjects under a harsh yoke. Mongol sources emphasize the demigod-like military genius of Genghis Khan, providing a perspective in the opposite extreme.

The most well known Mongolian work is “The Secret History of the Mongols”. It is renowned as the “oldest surviving Mongolian-language literary work.” The only existing text is a Ming Dynasty Chinese translation of a text originally in Uyghur script found by a Russian diplomat in Beijing a 1866. An original Mongolian copy has never been found. Much of what is known about the Mongols comes from this book, which has been dated to A.D. 1240. It is a history of Genghis Khan written for the Mongol royal family at a time when the Mongols had not been incorporated into China — the Mongols ruled the Han, not vice-versa. Its author is unknown.

folio from the Shahnama

Describing a traditional storyteller reading from one of the Mongol classics at the Lincoln Center Festival in New York, Edward Rothstein wrote in the New York Times, “In one of the final events of the recent, a lone Mongolian bard named Burenbayar came onstage and chanted “The Secret History of the Mongols." He had memorized the 13th-century text during long hours grazing animals on the steppes of Central Asia. And as is true of many ancient sagas, he sang of arms and the man — that is, of warfare and heroism. [Source: Edward Rothstein, New York Times, August 6, 2007]

“His subject was Genghis Khan, a conqueror of many peoples who was both barbarically ruthless and soulfully sentimental, reveling in revenge by tearing out an enemy's heart and liver with his bare hands while also forgiving, again and again, the bloody treachery of an envious childhood friend. He was at all times a warrior whose goal was conquest and whose demands could not be assuaged, except by victory. Almost every culture has such figures in their past, men like Odysseus, King David, Muhammad and Aeneas, whose triumphs were often attained through extreme, horrific battle. Such founding figures often also display powerful streaks of sensitivity and elevated vision along with prophetic abilities; on their broad chests and battle-readiness rest the later triumphs of their civilizations. But warriors don't have to display such qualifying attributes; throughout history they are revered. “

Three Greatest Mongol Historical Works

At the beginning of the 13th century, the Mongols created their written language. After that, various kinds of written works in history and literature appeared, one after another, and some of them were handed down to the present. The most famous ones are “Mongol Secret History”, “Mongol Golden History”,"Mongol Headstream”—which together are called the “Three Greatest Historical Works”. [Source: Liu Jun, Museum of Nationalities, Central University for Nationalities, Science of China, kepu.net.cn ~]

“Mongol Secret History” is also called “Yuan Dynasty Secret History," or “Yuan Secret History." In the Mongol language, it is called "Manghuotaniuchatuobuchaan". The author is unknown. The book was finished around the middle period of the 13th century. As to the exact year, some say that it was finished in 1228 (Heavenly Stem Five, Earthly Branch One), and others say it was 1240 (Heavenly Stem Seven, Earthly Branch One), and still others say 1252 (Heavenly Stem Nine, Earthly Branch One) and 1264 (Heavenly Stem One, Earthly Branch One). It is the first and greatest historical and literary work written in Mongolian. There are 282 sections in the book, which can be divided into 12 or 15 volumes. This chronological historical work describes all kinds of events that happened on the Mongolian Grassland, including the legends of Genghis Khan, according to the oral stories of the Mongols. At the same time, it depicts Mongol society, politics, economics, class relations, Genghis Khan's life story and historical facts during the rule of Wokuotai (Öködei, Ögödei, the third son of Genghis Khan). ~

page from an Ilkhanid Qu'ran

“Mongol Golden History” is chronological history written by the a famous Mongolian scholar, Luobizangdanjin. The book was finished around the end of the Ming dynasty and the beginning of the Qing dynasty in the 17th century. Regarded as the most complete history of the early Mongol, it tracks the history of the Mongols from ancient times to the late Ming and the early Qing period. The first part of the book re-records 233 of the 282 sections of the “Mongol Secret History”, and updates it with insights and discoveries that occurred after “Mongol Secret History” was written. The second half of the book makes use of books like “Essentials of Golden History” (See Below) and constructs a thorough record and supplement of Mongol history from Wokuotai to the late Ming and the early Qing period. This book has a Tibetan Buddhist slant as the author was a firm believer in that religion. The book is regarded as an important work in studying Mongolian history, especially that of the Ming dynasty. “Informative Golden History” is also translated into “Essentials of Mongol Golden History”, Aletan Tuopuchi, to distinguish itself from “Essentials of Golden History” (author unknown), generally called “Great Golden History." ~

“Mongol Headstream”, originally named “Hadun Wenjiaosunu Eerdeni Tuopuchi” in the Mongolian language, is a chronological history of The Mongols. The book was written in Mongol by Sanangchechen, who was an Ordos Mongol scholar, in the first year of the reign of Chinese Qing Emperor Kangxi (1662). Keerke The next year, it was translated into the Manchu language, and then into Chinese, and was named “Mongol Headstream” There are eight volumes in this book: the first two describe the general situation of Buddhism in India and Tibet; the rest record the history of The Mongols. The author referred to seven major sources in both Mongol and Tibetan language, including 1) “Original Meaning of the Essential Sculptures," 2) “History of the Reign of Khans," 3) Sublime Annulus Imperial Edict of Dharma History," and 4) “Ancient History of Mongolian Khans”. He combined information from these sources his own experience and knowledge to write the book, which covers the origin and spread of Buddhism, the origin of The Mongols, the stories of the kings in Yuan and Ming dynasty, among other things. The narratives on Dayan Khan and Anda Khan are especially informative. Although there are some questionable interpretations on the origin of the Mongols and also some mistakes in the events and years, the book is still considered a great contribution to the study of Mongolian history, literature and religion, especially during the Ming and Qing dynasty. ~

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: Asia for Educators, Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu; University of Washington’s Visual Sourcebook of Chinese Civilization, depts.washington.edu/chinaciv /=\; Library of Congress; New York Times; Washington Post; Los Angeles Times; China National Tourist Office (CNTO); Xinhua; China.org; China Daily; Japan News; Times of London; National Geographic; The New Yorker; Time; Newsweek; Reuters; Associated Press; Lonely Planet Guides; Compton’s Encyclopedia; Smithsonian magazine; The Guardian; Yomiuri Shimbun; AFP; Wikipedia; BBC. Many sources are cited at the end of the facts for which they are used.

Last updated February 2019