FOREST MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM

Phra Paisan is a modern forest monk. Thomas Fuller wrote in the New York Times: “His life is a portrait of traditional Buddhist asceticism. He lives in a remote part of central Thailand in a stilt house on a lake, connected to the shore by a rickety wooden bridge. He has no furniture, sleeps on the floor and is surrounded by books. He requested that a reporter meet him for an interview at 6 a.m., before he led his fellow monks in prayer, when mist on the lake was still evaporating.Urban monks stress scholarship while forest monks emphasize mediation.

According to Wikipedia: The Thai Forest Tradition is a tradition of Buddhist monasticism within Thai Theravada Buddhism. Practitioners inhabit remote wilderness and forest dwellings as spiritual practice training grounds. Maha Nikaya and Dhammayuttika Nikaya are the two major monastic orders in Thailand that have forest traditions. The Thai Forest Tradition originated in Thailand, primarily among the Lao-speaking community in Isan. [Source: Wikipedia]

The Thai Forest Tradition emphasizes direct experience through meditation practice and strict adherence to monastic rules (vinaya) over scholastic Pali Tipitaka study. Forest monks are considered to be meditation specialists. The Forest Tradition is usually associated with certain supernatural attainments (abhiñña). It is widely known among Thai people for its orthodoxy, conservatism, and asceticism. Because of these qualities, it has garnered great respect and admiration from the Thai people. dherents model their practice and lifestyle on those of the Buddha and his early disciples. They are referred to as 'forest monks' because they keep alive the practices of the historical Buddha, who frequently dwelt in forests, both during his spiritual quest and afterwards.

Vassa (in Thai, phansa), is a period of retreat for monastics during the rainy season (from July to October in Thailand). Many young Thai men traditionally ordain for this period, before disrobing and returning to lay life.

The Thai Forest Tradition stresses on meditation and strict adherence to monastic rules. Known for its orthodoxy, conservatism and asceticism, the Thais greatly respect monks who observe this tradition. Scaling new height: Sometimes there are no roads in the woods and you have to climb the rocks to get over the other side and continue your journey, says Ajahn Cagino. Once he did this ‘stunt’ and fell off the ledge. Fortunately, his fall was broken by the branches of a tree before he landed by the riverside. “I want to be a forest monk because Buddha himself spent much time dwelling in the forest. It is a strict, disciplined path,” says Cagino. [Source: Majorie Chiew, The Star, September 5, 2011]

Theravada Buddhism Websites: Readings in Theravada Buddhism, Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org/ ;

Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Encyclopædia Britannica britannica.com ;

Pali Canon Online palicanon.org ;

Vipassanā (Theravada Buddhist Meditation) Wikipedia article Wikipedia ;

Pali Canon - Access to Insight accesstoinsight.org ;

Forest monk tradition abhayagiri.org/about/thai-forest-tradition ;

BBC Theravada Buddhism bbc.co.uk/religion

See Separate Articles: MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM factsanddetails.com; NOVICE MONKS IN THERAVADA BUDDHISM AND THEIR ORDINATION factsanddetails.com

Origins of Forest Monks and the Pali Canon

In Thailand, Buddhism plays a central role in society. In the early 1900s, the urban monasteries often served as scholastic learning centers. Monks usually receive their education in monasteries and earn the rough equivalent of "graduate degrees" in Pali and Tipitaka studies, without necessarily engaging in the meditative practices described in the scriptures. During that period, it was also generally believed that it was no longer possible to achieve awakening. Because of the tendency in urban monastic life towards scholarship, debate, greater social activity and so on, some monks believed the original ideals of the monastic life (sangha) had been compromised. It was in part a reaction against this perceived dilution in Buddhism which led Ajahn Sao and Ajahn Mun to the simpler life associated with the forest tradition and meditation practice. Forest monasteries are situated far away from urban areas, usually in the wilderness or very rural areas of Thailand. One finds such monastic settings in other Buddhist countries as well such as Sri Lanka, Cambodia and Myanmar. The Forest Tradition revival is an attempt to reach back to past centuries before modernization, and reclaim old discipline standards, as an attempt to stave off increasing laxness in contemporary monastic life. [Source: Wikipedia]

In the early 1900s, Thailand's Ajahn Sao Kantasilo Mahathera and his student, Mun Bhuridatta led the Forest Tradition revival movement. In the 20th century notable practitioners included Ajahn Thate, Ajahn Maha Bua and Ajahn Chah. Theravada Buddhists regard the forest as part and parcel of the monastic training ground. As such, this training method was revived and maintained for the benefit of oneself and future generations. Myanmar and Sri Lanka have had their own forest traditions. It was later spread globally by Ajahn Mun's students including Ajahn Thate, Ajahn Maha Bua and Ajahn Chah and several western disciples, among whom the most senior is Luang Por Ajahn Sumedho.

The Thai Forest Tradition draws its inspiration from Pali Canon teachings contained in the Sutta and Vinaya Pitakas, where the Buddha is frequently described as dwelling in forests.[4] In the Pa-li discourses, the Buddha frequently instructs his disciples to seek out a secluded dwelling (in a forest, under the shade of a tree, mountain, glen, hillside cave, charnel ground, jungle grove, in the open, or on a heap of straw).[5] The Buddha himself achieved Awakening in a forest, under the foot of a Bodhi tree. In the Bhaya-bherava Sutta, the Buddha explained that the mental challenge he faced during his stay in the forest had aided his quest for Awakening.[6] There are many suttas in the Pali Canon where the Buddha instructs monks to practice in remote wilderness. Here are some examples:

monk in Khao Luang, Sukhothai, Thailand

1) In the Andhakavinda Sutta: 'Come, friends, dwell in the wilderness. Resort to remote wilderness & forest dwellings.' Thus they should be encouraged, exhorted, & established in physical seclusion. 2) In the Dantabhumi Sutta: Come you, monk, choose a remote lodging in a forest, at the root of a tree, on a mountain slope, in a wilderness, in a hill-cave, a cemetery, a forest haunt, in the open or on a heap of straw. 3) In the Maha-Saccaka Sutta: The household life is close and dusty, the homeless life is free as air. It is not easy, living the household life, to live the fully-perfected holy life, purified and polished like a conch shell. What if I, having shaved off my hair & beard and putting on the ochre robe, were to go forth from the home life into homelessness?

Meditation and Forest Monks

Meditation is a central component in the Thai forest tradition. Methods of meditation are numerous and diverse. Meditation methods frequently used by Ajahn Sao Kantasilo Mahathera and his student, Ajahn Mun Bhuridatta, are the walking meditation and the sitting meditation. Outside the sitting meditation session, the practitioner must be aware and mindful of his or her body and mind movements in all positions: standing, walking, sitting and lying. During sitting meditation, the mind is calmed with traditional practices such as mindfulness of breathing (anapanasati). The mental intoning of the mantra "Buddho" is used in order to maintain attention on the breath (in-breath is "Bud", out-breath is "dho") or the contemplation of the 32 body parts. The meditator goes through three levels of samadhi (concentration). In khanika-samadhi the mind is only calmed for a short time. In upacara-samadhi, approach concentration lasts longer. And in appana-samadhi, jha-na is attained. When sufficient concentration has been established, the three characteristics (impermanence, suffering and non-self) are contemplated, insight arises and ignorance is extinguished. No distinction is made between samatha meditation and insight (Vipassana) meditation; the two are used in conjunction. [Source: Wikipedia]

Luangpor Teean Jittasubho was a forest monk and a contemporary meditation master. He developed a meditation technique called Mahasati meditation. This method is a short cut for cultivating awareness. The practitioner pays attention to his or her body movements in all positions: standing, walking, sitting and lying. If the practitioner is aware of him or herself, then moha "delusion" will disappear. Mahasati Meditation does not call for reciting "in" or "out". There is no need to know whether one's exhalations or inhalations are long or short, fine or coarse, nor any need to perform rituals. This practice has frequently been called satipatthana because it is very similar to the method taught by the Buddha, in the Pali Canon, in the suttas of the same name (Maha Satipatthana Sutta found in the Digha Nikaya, sutta 22, Satipatthana Sutta found in the Majjhima Nikaya sutta 10, and an entire book where this practice is detailed throughout many short suttas, found in the Samyutta Nikaya section 47, titled "Satipatthana Samyutta"), but whatever people call it the point is to be aware of oneself. When thought arises the practitioner sees it, knows it and understands it. When he or she sees it, thought stops by itself. When thought stops, panna "knowing" arises, and she or he knows the source of dosa – moha – lobha "anger – delusion – greed". Then dukkha "suffering" will end.

Precepts, Customs and Ordination of Forest Monks

For forest monks there are several precept levels: Five Precepts, Eight Precepts, Ten Precepts and the Patimokkha. The Five Precepts (Pañcas'i-la in Sanskrit and Pañcasi-la in Pa-li) are practiced by laypeople, either for a given period of time or for a lifetime. The Eight Precepts are a more rigorous practice for laypeople. Ten Precepts are the training-rules for samaneras (male) and samaneris (female), novice monks and nuns. The Patimokkha is the basic Theravada code of monastic discipline, consisting of 227 rules for monks (bhikkhus) and 311 for nuns (bhikkhunis). Temporary or short-term ordination is so common in Thailand that men who have never been ordained are sometimes referred to as "unfinished." Long-term or lifetime ordination is deeply respected. The ordination process usually begins as an anagarika, in white robes. [Source: Wikipedia

A prominent characteristic of the Forest Tradition is great veneration paid toward Sangha elders. As such, it is vitally important to treat elders with the utmost respect. Care must be taken in addressing all monks, who are never to be referred to solely by the names they received upon ordination. Instead, they are to be addressed with the title "Venerable" before their name, or they may be addressed using just the Thai words for "Venerable," Ayya or Than (for men). All monks, on the other hand, can be addressed with the general term "Bhante". For monks and nuns who have been ordained 10 years or more, the title Ajahn, meaning "teacher", is reserved. For community elders the title Luang Por is often used, which in Thai can roughly translate into "Venerable Father".

In Thai culture, it is considered impolite to point the feet toward a monk or a statue in the shrine room of a monastery. It is equally considered impolite to address a monk without making the anjali gesture of respect. When making offerings to the monks, it is considered inappropriate to approach them at a higher level than they are at - for instance, if a monk is sitting it would be inappropriate to approach that monk and stand over them while making an offering.

In practice, the extent to which this cultural code of behavior is enforced will vary greatly, with some communities being more lax about such cultural codes than others. The one element which the forest monastic community are not lax about is the standard Theravada monastic code (vinaya). Although Forest monasteries exist in extremely rural environments, they are not isolated from society. Monks in such monasteries are expected to be an integral element in the surrounding society in which they find themselves.

Wat Tham Suea

Wat Tham Suea

Wat Tham Suaa (eight kilometers northeast of Krabi) is the most famous of southern Thailand’s forest temples. According to Lonely Planet: The main wíha(an (hall) is built into a long, shallow limestone cave. On either side of the cave, dozens of kùtì (monastic cells) are built into various cliffs and caves. You may see a troop of monkeys roaming the grounds. The most shocking thing about Wat Tham Seua is found in the large main cave. Alongside large portraits of Ajahn Jamnien Silasettho, the wat’s abbot who has allowed a rather obvious personality cult to develop around him, are close-up pictures of human entrails and internal organs, which are meant to remind guests of the impermanence of the body. Skulls and skeletons scattered around the grounds are meant to serve the same educational purpose.

Ajahn Jamnien, who is well known as a teacher of Vipassana (insight meditation) and Metta (loving kindness), is said to have been apprenticed at an early age to a blind lay priest and astrologer who practised folk medicine, and has been celibate his entire life. On the inside of his outer robe, and on an inner vest, hang scores of talismans presented to him by his followers – altogether they must weigh several kilograms, a weight Ajahn Jamnien bears to take on his followers’ karma. Many young women come to Wat Tham Seua to practise as eight-precept nuns.

The best part of the temple grounds can be found in a little valley behind the ridge where the bòt (central sanctuary) is located. Walk beyond the main temple building keeping the cliff on your left and you’ll come to a pair of steep stairways. The first leads to a truly arduous climb of over 1200 steps – some of them extremely steep – to the top of a 600m karst peak. The fit and fearless will be rewarded with a Buddha statue, a gilded stupa and great views of the surrounding area; on a clear day you can see well out to sea.

The second stairway, next to a large statue of Kuan Yin (the Mahayana Buddhist Goddess of Mercy), leads over a gap in the ridge and into a valley of tall trees and limestone caves. Enter the caves on your left and look for light switches on the walls – the network of caves is wired so that you can light your way, chamber by chamber, through the labyrinth until you rejoin the path on the other side. If you go to the temple, please dress modestly: pants down to the ankles, shirts covering the shoulders and nothing too tight. Travellers in beachwear at Thai temples don’t realise how offensive they are and how embarrassed they should be

Life of a Forest Monk

Majorie Chiew wrote in the Malaysian newspaper The Star: “Venerable Ajahn Cagino, 43, lives in a cave with two snakes and eight bats. The cave is two kilometers from the nearest village in Mae Hong Son in northern Thailand. Nestled in a deep valley hemmed in by high mountain ranges that border Myanmar, Mae Hong Son is isolated from the outside world and is covered with mist throughout the year. “I’ve had enough of wandering,” says the Malaysian monk of the Thai Forest Tradition, which is a branch of Theravada Buddhism.[Source: Majorie Chiew, The Star, September 5, 2011]

For 12 years, Cagino had been walking through the remotest jungles of Thailand, before settling down in a cave. It was all part of the spiritual training of a forest monk.During the past 12 years, he was in and out of the forest with other monks. But six years ago, Cagino set off alone into the deep wilderness to experience what it was like to be a forest monk. All he had with him were five pieces of cloth, an alms bowl, cup, umbrella, mosquito net and walking stick. “The stick is important as we can make some noise to warn snakes and other creatures of our presence when we’re walking through the forest,” says Cagino. Cagino described his wandering years as a journey of exploration and discovery, not a time of hardship. “I enjoyed those years even though I know not if there was a meal for tomorrow or where I was heading. I just walked on to see the world,” he says.

A forest monk leads a nomadic life as he moves from one place to another to find the ideal location to practise meditation. He usually camps by the river for easy access to water supply. “We stay 15 days at the most at one place; not too long as we’re not supposed to feel attached to a place,” says Cagino. “If a place has ample food and shelter but is not conducive for meditation, we must leave promptly. If the place is great for meditation, the forest monk will stay a bit longer. It allows us to enhance our wisdom.” Sometimes Cagino would ask villagers for directions to caves where monks had previously stayed. “There may be a fireplace and an old kettle left behind. Sometimes I will borrow a hammer and nails to make a seat for meditation,” says Cagino.

The life of a forest monk is not without its challenges. There are times when they have to track through muddy paths, cross streams and rivers, or climb down cliffs. One can easily get lost in the jungle, too. The forest monk will usually stay 2-3km from the nearest village so that he can go for alms in the morning. He accepts only food, never money. 1Once, Cagino came upon a little girl who blocked his path. He noticed she had something to give. He lowered his alms bowl and she placed a packet of rice, vegetables and a carton of milk in his bowl. “When I was about to eat, I found a toy egg on the rice. I was touched that the little girl, out of the pureness of her heart, decided to give dana (food offering) to a monk!”

Cagino was professional photographer before he became a forest monk Despite his success, Cagino did not find happiness and fulfilment. As a photographer, he had to keep honing his skills. “What used to be the best photo was not the best anymore. At the next photo contest, you’ve to improve your skills and get the winning shot,” he says. “Nothing seems to be the ultimate.” Floating to the other shore: Meditating on a bamboo raft for spiritual tranquility. Cagino was miserable and disillusioned, and wondered if there was more to life than its never-ending challenges. At 27, Cagino turned his back on all material pursuits, sold off his worldly belongings, and became a monk.

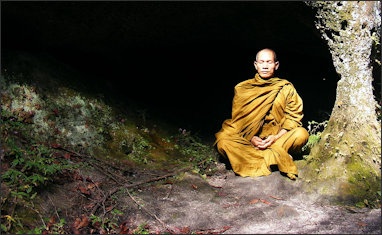

"A Monk Rests in the Forest"

Over the next two years, Cagino visited forest monasteries in Thailand and New Zealand to learn more about Buddhism. Cagino was ordained as a samanera (novice monk) at 29, and stayed at Ang Hock Si Temple in Perak Road, Penang, for the next one-and-a-half years. He trained as a forest monk under Thai master Ajahn Ganha for five years, and was re-ordained at Wat Pah Nanachat (The International Forest Monastery), a Buddhist monastery in north-east Thailand, in the Theravada Forest Tradition.

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: East Asia History Sourcebook sourcebooks.fordham.edu , Asia for Educators, Columbia University; Asia Society Museum “The Essence of Buddhism” Edited by E. Haldeman-Julius, 1922, Project Gutenberg, Virtual Library Sri Lanka; “World Religions” edited by Geoffrey Parrinder (Facts on File Publications, New York); “Encyclopedia of the World's Religions” edited by R.C. Zaehner (Barnes & Noble Books, 1959); “Encyclopedia of the World Cultures: Volume 5 East and Southeast Asia” edited by Paul Hockings (G.K. Hall & Company, New York, 1993); BBC, Wikipedia, National Geographic, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Smithsonian magazine, The New Yorker, Reuters, AP, AFP, and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2024