SOUTH CHINA SEA AND SPRATLY ISLANDS

The South China Sea is the world's largest sea. According to the Guinness Book of Records, it covers 1,148,500 square miles. In the last 2,500 years mariners for Malaysia, China and Indonesia navigated the South China Sea to trade sandalwood, silk, tea and spices. Today it carries roughly a third of the world's shipping and accounts for a tenth of the world's fish catch. China, Vietnam, Taiwan, Malaysia, Indonesia, Brunei and the Philippines all have 200-mile coastal economic zones in the South China Sea. All of these countries also claim the Spratly Islands which are in the middle of the sea

About $5.3 trillion of global trade passes through the South China Sea each year, $1.2 trillion of which passes through U.S. ports. Below the South China Sea is an estimated $3 trillion worth of oil, gas and minerals. Fisheries in the South China Sea have been decimated by overfishing and polluting chemicals from shrimp farms and factories. By some estimates there is enough oil under the South China Sea to last China for 60 years.

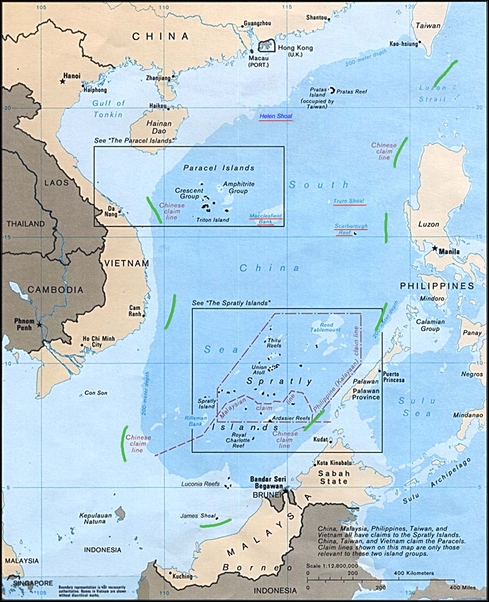

The Spratly Islands are a group of tiny islands, reefs, shoals and rocks in the South China Sea claimed by China, Vietnam, the Philippines, Taiwan, Malaysia, Brunei and Indonesia. Most of the islands are submerged during high tide and generally regarded as uninhabitable. No one paid much attention to them until the 1960s when it was realized there could be mineral wealth and oil deposits located in the waters around them. [Source: Tracy Dahlby, National Geographic, December 1998]

The Spratlys and Paracels straddle busy shipping lanes. United Nations Convention on the Law of the Seas states that countries have exclusive economic zones in areas within 200 nautical miles of their shores. In the South China Sea, particularly in the Spratly Islands, these zones overlap. When a country claims the Spratly Islands it also claims the waters win a 200 nautical mile radius around them.

Dozens of fishermen and sailors have been killed in disputes involving the Spratly Islands. Also naval vessels have faced off, fishermen have been arrested, oil rigs have been blockaded and occasionally shots are fired.

Dispute in the South China Sea

The South China Sea has long been regarded, together with the Taiwan Strait and the Korean Peninsula, as one of East Asia's three major flashpoints. Gareth Evans wrote in Project Syndicate: “More neighbouring states have more claims to more parts of the South China Sea - and tend to push those claims with more strident nationalism - than is the case with any comparable body of water. And now it is seen as a major testing ground for Sino-American rivalry, with China stretching its new wings, and the United States trying to clip them enough to maintain its own regional and global primacy. [Source: Gareth Evans, Project Syndicate, Christian Science Monitor, July 30, 2012. Evans was Foreign Minister of Australia from 1988-1996 and is President Emeritus of the International Crisis Group]

The legal and political issues associated with the competing territorial claims - and the marine and energy resources and navigation rights that go with them - are mind-bogglingly complex. Future historians may well be tempted to say of the South China Sea question what Lord Palmerston famously did of Schleswig-Holstein in the nineteenth century: 'Only three people have ever understood it. One is dead, one went mad, and the third is me - and I've forgotten.'

The core territorial issue currently revolves around China's stated interest -- imprecisely demarcated on its 2009 'nine-dashed line' map - in almost the entire Sea. Such a claim would cover four disputed sets of land features: the Paracel Islands in the northwest, claimed by Vietnam as well; the Macclesfield Bank and Scarborough Reef in the north, also claimed by the Philippines; and the Spratly Islands in the south (variously claimed by Vietnam, the Philippines, Malaysia, and Brunei, in some cases against each other as well as against China.)

There has been a scramble by the various claimants to occupy as many of these islands - some not much more than rocks - as possible. This is partly because, under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea, which all of these countries have ratified, these outcroppings' sovereign owners can claim a full 200-mile Exclusive Economic Zone (enabling sole exploitation of fisheries and oil resources) if they can sustain an economic life of their own. Otherwise, sovereign owners can claim only 12 nautical miles of territorial waters.

What has heightened ASEAN'S concern about Beijing's intentions is that even if China could reasonably claim sovereignty over all of the land features in the South China Sea, and all of them were habitable, the Exclusive Economic Zones that went with them would not include anything like all of the waters within the dashed-line of its 2009 map. This has provoked fears, not unfounded, that China is not prepared to act within the constraints set by the Law of the Sea Convention, and is determined to make some broader history-based claim.

Spratly Islands and China

The Chinese have built minbases for helicopters and naval cargo and grown cabbages, tomatoes and cucumber of floating platforms on the Spratlys. Some people call Chinese activity as a "creeping invasion." Pessimists worry that a dispute in the Spraty Islands could evolve in showdown between the United States and China.

In regard to the Spratly Island China’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu said, “China enjoys indisputable sovereign rights on the South China Sea islands and their adjacent waters.” At an ASEAN meeting a Chinese representative intimidatingly told the representative from Southeast Asia, “China is a big country and other countries are small countries and that’s just a fact.”

China Maritime Surveillance is in charge of watching over the vast area of sea that China claims. The agency has 300 vessel of various types and 10 aircrafts. In May 2011 it announced it was going to raise the number of personnel by 10,000 and purchase 36 new ships over five years.

Oil, Gas, Fishing, Shipping and the Spartlys Islands and South China Sea

At stake is not just the islands themselves, but also the fishing rights in the waters around them and the rights to potential reserves of oil which might exist on the nearby continental shelf. Oil as not been discovered there. Drilling would set off an international crisis. One Navy officer told National Geographic, "I just hope they don't find oil in the Spratlys."

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post The are believed to be large supplies of natural gas beneath the Spratlys and large amounts of oil and gas elsewhere in the South China Sea but nobody yet really knows the true extent of it. In the absence of detailed surveys, estimates vary widely, though even a low-ball figure by the U.S. Geological Survey estimates that the South China Sea could contain nearly twice China’s known reserves of oil and plenty of gas, too. China’s own estimates are many times higher.

Control of the Spratly Islands also means control of some of the world’s most important shipping lanes. The Spratly Islands are 1,700 miles from the Strait of Malacca, one of the world's busiest shipping lanes. Everyday 200 merchant vessels, including ships that carry 80 percent of Japan's oil, pass through waters around the Spratly Islands.

History of the Dispute Over the Spratly Islands

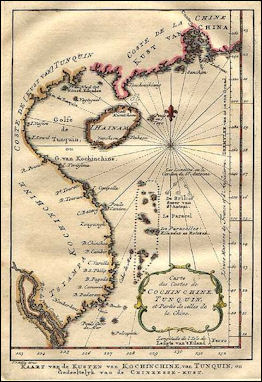

Vietnam map from 1754

China claims all of the Spratly Islands and claims its claims date backs 2000 years to the Han dynasty. Beijing uses a "talk and take" strategy, simply stating the islands are "indisputably" their sovereign territory and showing all them with Chinese territorial waters on Chinese maps. After World War II, the Taiwan government said they had the Chinese claim to the islands, and in turn occupied the largest island of Taiping.

Vietnam annexed the Spratly Islands in 1933 when the country was controlled by French. After that the Philippines declared the islands was theirs. In 1974, after the U.S. military left South Vietnam, China grabbed the Paracel Islands claimed by China and Vietnam. Vietnam later occupied the westernmost islands but China halted their expansion plans in 1988 by taking six reefs from Vietnam, sinking three Vietnamese ships and killing at least 70 sailors.

China has used arcane issues of international law and ancient shards of pottery as evidence of its “indisputable sovereignty” over the South China Sea. Some date the dispute back to 1947, when the doomed Chinese government of Chiang Kai-shek issued a crude map with 11 dashes marking as Chinese almost the entire 1.3 million-square-mile waterway. The Communist Party toppled Chiang but kept his map and his expansive claims, though it trimmed a couple of dashes.

In 2002, 10-member Association of Southeast Asian Nations and China signed a nonbinding accord that calls for maintaining the status quo. The Declaration on the Conduct of Parties (DOC) that was signed seeks to resolve the territorial disputes of the signers by peaceful means and in accordance with international law, including the 1982 UN Convention on the Law of the Sea. The agreement however has little teeth. China wants to engage claimants individually — against the wishes of countries like the Philippines that want to negotiate as a bloc. Diplomats say that China seems to favor one-on-one talks withe each ASEAN nation, fearing the group could gang up on it if acting together.

In 2006, China, Vietnam and the Philippines cooperated in the joint exploration of the Spratly’s area for oil and gas using the Nanhai 502, a 731-ton Chinese sea-bed geology research. In 2007, China complained about a $2 billion gas pipeline project in the South China Sea through Vietnam

In March 2009, official Chinese news organizations reported that the government intended to bolster its naval presence in the South China Sea by sending six more patrol vessels to the region in the next three to five years. The official reason was to curb illegal fishing. But the announcement came after tensions with the Philippines rose over the disputed Nansha Islands, which the Filipino government claimed as its territory in a law passed on March 10. [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, April 21, 2009]

In 2010, China stepped up its activities regarding its claims to the South China Sea and the Spratly Islands, It warned Exxon Mobile and BP to stop exploring for oil and gas in offshore areas near Vietnam. Vietnamese fishing vessels have been seized and their crews have been detained for fishing in disputed waters. In 2010 in waters around Indonesia's Natuna Islands, a showdown occurred between an Indonesian patrol vessel trying to seize Chinese boats engaged in illegal fishing operations and an armed Chinese vessel protecting them.

See Separate articles on the SPRATLY ISLAND DISPUTES WITH VIETNAM AND THE PHILIPPINES

Mischief Reef

In 1995, China took over a reef, appropriately name Mischief reef, also claimed by the Philippines, in the Spratly Islands The reef — a doughnut-shaped ring of coral several miles in diameter — is 125 nautical miles west of the Philippine Island of Palawan, and well within the Philippines 200 mile economic zone, and 700 nautical miles from Hainan Island, the nearest piece of China land. The move took place not long after the United States closed its bases in the Philippines.

On Mischief reef, the Chinese dynamited a break through the coral, built four bunkers and some bamboo huts and erected a pole flying the Chinese flag. The Filipino navy blew up one of the huts; China confronted a Philippine vessel; a Hong Kong magazine suggested that China might make a military strike at the Philippines.

When China claims a reef, it first puts down a buoy, then builds a concrete marker, followed by makeshift wooden and bamboo huts. Sometimes the markers are discovered and blown up. If they are left undisturbed they build larger and more permanent structures.

In November 1998, a Philippine reconnaissance planes discovered two concrete fort-like building on Mischief reef, where there were only wooden structure before. The structures have command posts, satellite communications equipment, observation towers and a helicopter pad. Beijing claims the men on the island are fisherman but Philippine authorities claim they are spies, saying they wear tracksuits, they arn’t tanned and don’t have rough hands like normal fisherman and "don't even act like fishermen."

In March 2009. China upset some its neighbors by sending a patrol boat into a disputed area around the Spratly Islands.

China’s Motives and Expectations in the South China Sea

Jim Holmes wrote in Foreign Policy: China's motives in the South China Sea — have remained remarkably constant over the decades. Indeed, the map on which the nine-dashed line is inscribed is an artifact from the 1940s, not something dreamed up in recent years. Chiang Kai-shek's government published it before fleeing to Taiwan, and the Chinese communist regime embraced it. Now as then, the map visually expresses China's interests and aspirations. Oil and natural gas deposits thought to lie in the seabed obsessed maritime proponents -- most notably Deng Xiaoping, the father of China's economic reform and opening project. Fuel and other raw materials remain crucial to China's national development project three decades after Deng launched it. [Source: Jim Holmes, Foreign Policy, July 26, 2012]

The motive of averting superpower encirclement has also influenced Chinese strategy. By the late 1970s, Deng had come to believe that the Soviet Union was pursuing a "dumbbell strategy" designed to entrench the Soviet navy as the dominant force in the Indian Ocean and Western Pacific. The Strait of Malacca was the bar connecting the two theaters. To join them, Moscow had negotiated basing rights in united Vietnam, at Cam Ranh Bay and Da Nang. Beijing believed it had to forestall a Soviet-Vietnamese alliance. Indeed, the PLA undertook a cross-border assault into Vietnam in 1979 in large part to discredit Moscow as Hanoi's defender.

Beijing may view the 2007 U.S. maritime strategy -- the official U.S. Navy, Marine Corps, and Coast Guard statement on how the sea services see the strategic environment and intend to manage it -- as a throwback to Moscow's dumbbell strategy, predicated as it is on preserving and extending American primacy in the Western Pacific and the greater Indian Ocean. Chinese strategists fret continually about American encirclement, especially as the United States "pivots" to Asia. For China, it seems, everything old is new again. Nor should we overlook honor as a motive animating Beijing's actions. Recouping China's honor and dignity after a "century of humiliation" at the hands of seaborne conquerors was a prime mover for Chinese actions in 1974 and 1979. It remains so today. The China seas constitute part of what the Chinese regard as their country's historical periphery. China must make itself preeminent in these expanses.

Expectations are sky-high among the Chinese populace. Having regularly described their maritime territorial claims as a matter of indisputable sovereignty, having staked their own and the country's reputation on wresting away control of contested expanses, and having roused popular sentiment with visions of seafaring grandeur, Chinese leaders will walk back their claims at their peril. They must deliver -- one way or another.

And they have the means to do so. China has amassed overpowering naval and military superiority over any individual Southeast Asian competitor. The Philippines possesses no air force to speak of, while retired U.S. Coast Guard cutters are its strongest combatant ships. Vietnam, by contrast, shares a border with China and fields a formidable army. Last year, Hanoi announced plans to buttress its naval might by purchasing six Russian-built Kilo-class diesel submarines armed with wake-homing torpedoes and anti-ship cruise missiles. A Kilo squadron will supply Vietnam's navy a potent "sea-denial" option. But Russia has not yet delivered the subs, meaning that Hanoi can mount only feeble resistance to any Chinese naval offensive. That's still more reason for China to lock in its gains now, before Southeast Asian rivals start pushing back effectively.

Complexity of the South China Sea and Spratly Island Disputes

Neil Chatterjee of Reuters wrote: “The need for import-dependent Asian countries to secure energy supplies has led to many protracted disputes, as areas of potential wealth lie on strategic shipping lanes in a region where losing litigation may mean losing face and influence...Agreeing maritime boundaries start with political leadership at the top, which requires the backing of the people on issues that have led to public protests and gunboat diplomacy in Asian waters in recent years. Persuading oil firms to wade in disputed waters may not be easy, given the legal and fiscal uncertainties that add to soaring exploration costs and the risk of drilling dry wells.[Source: Neil Chatterjee. Reuters, April 30, 2007]

"It's extremely hard for governments to compromise on territory," Clive Schofield, research fellow at the Australian National Centre for Ocean Resources and Security, told Reuters. "If you draw up definite boundaries, then you run the risk that the majority or all the resources at stake may end up on the wrong side -- this uncertainty promotes deadlock."

Claims rest on the intricacies of international rules, based on the 1982 U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea, ambiguous on topics such as the difference between islands and rocks that each allow different sea territory. But a successor is unlikely. "Most states would be deeply wary of going back and opening Pandora's Box," said Schofield. And other factors such as strategic influence are especially important in disputes with China, looking to maintain open sea routes to secure its booming commodity shipments or to help its military in the event of any hostilities with rival Taiwan.

Noel Tomnay at energy consultancy Wood Mackenzie in Singapore told Reuters. "Border issues are holding up prospective areas of acreage -- but a lot are quietly being resolved." The key to solving these disputes will be separating territorial claims from joint agreements to explore for oil, and then agreeing how to divide up the resources. This could involve one country claiming tax and passing some on to the other, or a joint authority to issue permits and remit proceeds. "You can agree to disagree -- to explore and to develop natural resources under the sea, without giving up the rights to fishing or to patrol the area," said Tomnay.

This distinction is seen as the secret to successful Malaysian agreements with Thailand and Vietnam, and between Australia and East Timor, where the two sides established joint development zones instead of formal boundary lines and the $5 billion development of the Greater Sunrise gas fields may begin soon. But these agreements have still been protracted affairs. “These things can be glacial -- but countries are acting and in diplomatic terms this looks like Formula One,” Tomnay said. Any next step will be to agree how to divide exploration blocks. "Countries will go to war for resources but for small amounts of oil it's risking a lot," said Flynn.

China Seems to Be Opting for the Military Option in the South China Sea

China's naval might is far superior to that of the Philippines and other nations near China. China even has a plan to deploy its first aircraft carrier soon. Jim Holmes wrote in the Foreign Policy: “Beijing is reaching for its weapons” as it did in the battle over the Paracel islands in 1974. “Unlike in 1974, however, Chinese leaders are doing so at a time when peacetime diplomacy seemingly offers them a good chance to prevail without fighting. I call it "small-stick diplomacy" -- gunboat diplomacy with no overt display of gunboats. [Source: Jim Holmes, Foreign Policy, July 26, 2012]

Chinese strategists take an extraordinarily broad view of sea power — one that includes nonmilitary shipping. In 1974, propagandists portrayed the "Defensive War for the Paracels" (as the conflict is known in Chinese) as the triumph of a "people's navy," lavishly praising the fishermen who had acted as a naval auxiliary. Fishing fleets can go places and do things to which rivals must respond or surrender their claims by default. Unarmed ships from coast-guard-like agencies constitute the next level. And the PLA Navy fleet backed by shore-based tactical aircraft, missiles, missile-armed attack boats, and submarines represents the ultimate backstop.

Beijing can solidify its hold within the nine-dashed line by dispatching surveillance, fisheries, or law-enforcement ships to protect Chinese fishermen in disputed waters, stare down rival claimants, and uphold Chinese domestic law. And it can do so without overtly bullying weaker neighbors, giving extraregional powers a pretext to intervene, or squandering its international standing amid the anguish and sheer messiness of armed conflict. Why jettison a strategy that holds such promise?

Because small-stick diplomacy takes time. It involves creating facts on the ground -- like Sansha -- and convincing others it's pointless to challenge those facts. Beijing has the motives, means, and opportunity to resolve the South China Sea disputes on its terms, but it may view the opportunity as a fleeting one. Rival claimants like Vietnam are arming. They may acquire military means sufficient to defy China's threats, or at least drive up the costs to China of imposing its will. And Southeast Asians are seeking help from powerful outsiders like the United States. Although Washington takes no official stance on the maritime disputes, it is naturally sympathetic to countries of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN). Some, like the Philippines, are treaty allies, while successive U.S. administrations have courted friendly ties with Vietnam.

So a window of opportunity remains open for Beijing -- for now. Chinese diplomacy recently thwarted efforts to rally ASEAN behind a "code of conduct" in the South China Sea. Washington has announced plans to "rebalance" the U.S. Navy, shifting about 60 percent of fleet assets to the Pacific and Indian Ocean theaters. But the rebalancing is a modest affair. More than half of the U.S. Navy is already in the theater, and the rebalancing will take place in slow motion, spanning the next eight years.

Chinese leaders thus may believe they must act now or forever lose the opportunity to cement their control of virtually the entire South China Sea. More direct methods may look like the least bad course of action -- whatever the costs, hazards, and diplomatic blowback they may entail in the short run. Beijing may have concluded that patient diplomacy will forfeit its destiny in the South China Sea. In Chinese eyes, it's better to act now -- and preempt the competition. The lesson of 1974: Timing is everything.

Salami Slicing in the South China Sea

On Chinese policy in the South China Sea, Robert Haddick wrote in Foreign Policy, “What about an adversary that uses "salami-slicing," the slow accumulation of small actions, none of which is a casus belli, but which add up over time to a major strategic change? U.S. policymakers and military planners should consider the possibility that China is pursuing a salami-slicing strategy in the South China Sea, something that could confound Washington's military plans. [Source: Robert Haddick, Foreign Policy, August 3, 2012]

“Appendix 4 of this year's annual Pentagon report on China's military power displays China's South China Sea claim, the so-called "nine-dash line," along with the smaller claims made by other countries surrounding the sea. A recent BBC piece shows China's territorial claim compared to the 200-nautical mile exclusive economic zones (EEZs) that the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea has granted to the countries around the sea. The goal of Beijing's salami-slicing would be to gradually accumulate, through small but persistent acts, evidence of China's enduring presence in its claimed territory, with the intention of having that claim smudge out the economic rights granted by UNCLOS and perhaps even the right of ships and aircraft to transit what are now considered to be global commons. With new "facts on the ground" slowly but cumulatively established, China would hope to establish de facto and de jure settlements of its claims.

“On the eve of the ill-fated Phnom Penh summit, the China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC), a state-owned oil developer, put out a list of offshore blocks for bidding by foreign oil exploration companies. In this case, the blocks were within Vietnam's EEZ -- in fact, parts of some of these blocks had already been leased by Vietnam for exploration and development. Few analysts expect a foreign developer such as Exxon Mobil to legitimize China's over-the-top grab of Vietnam's economic rights. But CNOOC's leasing gambit is another assertion of China's South China Sea claims, in opposition to UNCLOS EEZ boundaries most observers thought were settled.

“China's actions look like an attempt to gradually and systematically establish legitimacy for its claims in the region. It has stood up a local civilian government, which will command a permanent military garrison. It is asserting its economic claims by leasing oil and fishing blocks inside other countries' EEZs, and is sending its navy to thwart development approved by other countries in the area. At the end of this road lie two prizes: potentially enough oil under the South China Sea to supply China for 60 years, and the possible neutering of the U.S. military alliance system in the region.

“Meanwhile, The Pentagon intends to send military reinforcements to the region and is establishing new tactical doctrines for their employment against China's growing military power. But policymakers in Washington will be caught in a bind attempting to apply this military power against an accomplished salami-slicer. If sliced thinly enough, no one action will be dramatic enough to justify starting a war. How will a policymaker in Washington justify drawing a red line in front of a CNOOC oil rig anchoring inside Vietnam's EEZ, or a Chinese frigate chasing off a Philippines survey ship over Reed Bank, or a Chinese infantry platoon appearing on a pile of rocks near the Spratly Islands? When contemplating a grievously costly war with a major power, such minor events will appear ridiculous as casus belli. Yet when accumulated over time and space, they could add up to a fundamental change in the region.

A salami-slicer puts the burden of disruptive action on his adversary. That adversary will be in the uncomfortable position of drawing seemingly unjustifiable red lines and engaging in indefensible brinkmanship. For China, that would mean simply ignoring America's Pacific fleet and carrying on with its slicing, under the reasonable assumption that it will be unthinkable for the United States to threaten major-power war over a trivial incident in a distant sea. But what may appear trivial from a U.S. perspective could be vital to players like the Philippines and Vietnam, who are attempting to defend their territory and economic rights from an outright power grab. This fact may give these countries a greater incentive to be more aggressive than the United States in defending against China's encroachments. And should shooting break out between China and one of these small countries, policymakers in Beijing will have to consider the reputational and strategic consequences of blasting away at a weaker neighbor.

Both the United States and ASEAN members would greatly prefer a negotiated code of conduct for resolving disputes in the South China Sea. But should China opt to pursue a salami-slicing strategy instead, policymakers in Washington may conclude that the only politically viable response is to encourage the small countries to more vigorously defend their rights, even if its risks conflict, with the promise of U.S. military backup. This would mean a reversal of current U.S. policy, which has declared neutrality over the sea's boundary disputes.

The United States has stayed neutral because it doesn't want to pre-commit itself to a sequence of events over which it may have no control. That approach is understandable but will increasingly conflict with security promises it has made to friends in the region and to the goal of preserving the global commons. Policymakers and strategists in Washington will have to ponder what, if anything, they can do against a such a sharp salami-slicer.

Dispute Between ASEAN and China Over the South China Sea

China has insisted on handling the disputes with other nations on a one-on-one basis rather than multilaterally, a strategy some critics have described as "divide and conquer". China says its sovereignty is indisputable and historically based. In 1992, China enacted the law in the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone, triggering a territorial dispute in the South China Sea between ASEAN (a group of 10 Southeast Asian nations) and Beijing. On the basis of the law, China regards various islands in the sea as its territory. [Source: Takashi Shiraishi, Yomiuri Shimbun, February 7, 2011]

Takashi Shiraishi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: In response, ASEAN adopted the Declaration on the South China Sea in 1992, emphasizing "the necessity to resolve all sovereignty and jurisdictional issues by peaceful means, without resort to force" and calling for the establishment of "a code of international conduct" over the disputed waters. But in 1995, China, advocating the bilateral approach in settling the disputes, occupied Mischief Reef, which is claimed by the Philippines.

In 2000, China modified its policy toward ASEAN. As a result, China and ASEAN concluded in 2002 the Framework Agreement on Comprehensive Economic Cooperation and the Joint Declaration on Cooperation in the Field of Nontraditional Security Issues and signed the Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea. In 2003, China subscribed to the Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia--ASEAN's signature pact of association. However, the 2002 declaration on the conduct of parties is not legally binding and China has refused to accede to any binding code with ASEAN in this respect.

Takashi Shiraishi wrote in the Yomiuri Shimbun: The disputes initially flared up in 2007, when Beijing created a symbolic administrative region, named Sansha, to administer two archipelagoes--the Paracel and Spratly islands--and the Macclesfield submarine bank in the South China Sea. In response, Vietnam this year adopted a law of the sea claiming sovereignty over both the Paracels and the Spratlys. Soon afterward, China reciprocated with the announcement that it would establish a military presence in the newly established city of Sansha. Furthermore, incidents have frequently taken place in the South China Sea in recent years, in which oil and natural gas exploration activities have been interrupted or fishing boats have been detained. [Source: Takashi Shiraishi, Yomiuri Shimbun, September 24, 2012. Shiraishi is president of both the National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies and the Institute of Developing Economies, Japan External Trade Organization]

Chinese Fishermen Who Fish in the South China Sea Subsidized by Beijing

Kor Kian Beng wrote in the Straits Times: “In Tanmen, a fishing village of 32,000 tucked in the eastern corner of Hainan island, there is little diplomacy when it comes to tension in the South China Sea, believed to contain huge energy reserves. Nearly half the residents of the village are fishermen who regularly trawl near the waters claimed by China, the Philippines, Vietnam, Malaysia, Brunei and Taiwan. For them, the dispute is brutal, bloody and sometimes deadly. [Source: Kor Kian Beng, Straits Times, August 31, 2012]

Yet, the Chinese government gives subsidies to fishermen who work the disputed waters, such as in the Spratlys, in an otherwise loss-making venture. Fishermen say they get annual fuel subsidies based on the horsepower of their boats. For instance, Chen received about 400,000 yuan ($63,000) in such subsidies last year for his 750-horsepower boat, while Pu Mingkuang got about 300,000 yuan for his 600-horsepower boat. They say they get an additional subsidy of about 5,000 yuan each time they make a fishing trip to the Spratlys.

Government officials have visited Tanmen village and urged them to continue fishing in the Spratlys so as to protect China's sovereignty claims against others, fisherman Chen Yibin told the Strait Times, adding, "I agree we have to do that, even without the subsidies. It's like you have a piece of land and if you never bother to tend to it, others will sneak in and claim it as theirs."

Maritime security expert Zhang Hongzhou of Singapore's S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies observed in a recent paper that China is encouraging its fishermen to venture to faraway waters such as those around the Spratlys because of depleting fishery resources in its inshore waters. "These operations become triggers for maritime tensions and clashes in the region," he wrote. Agreeing, analyst Ian Storey from Singapore's Institute of Southeast Asian Studies believes the monetary incentives could increase tensions. "As we have seen in the recent past, it will lead to arrests and detentions, ramming of boats and even to exchanges of gunfire," he says. "To my mind, it's just a question of time before one of these incidents turns really ugly and people get killed."

Violence Involving Chinese Fishermen in the South China Sea

Chinese fisherman Chen Yibin alleges that Philippine troops boarded the boat his cousin was on and opened fire, killing the 20-year-old and other crew members when they were fishing in the Spratlys in 2007. Kor Kian Beng wrote in the Straits Times: “Chen Yibin ended up having to pack his 20-year-old relative's body into a freezer that was meant to store fish, as he made a three-day dash back to their hometown here. To this day, Chen believes his cousin was killed by Filipino soldiers who boarded the Chinese fishermen's boat, charging that it had strayed into Philippine waters and then firing at them. [Source: Kor Kian Beng, Straits Times, August 31, 2012]

Citing survivors' accounts, Chen, who was on another boat when the shooting took place, claims several other crew members were killed or injured. His account cannot be independently verified. "I hate the Philippines for what it did. How could it be so cruel?" says Chen, holding up a clenched fist. "If China goes to war against the Philippines, I will be the first to sign up to fight them."

As it is, most of Tanmen's fishermen can tell stories of run-ins with foreign navies, from being chased away to having warning gunshots fired into the air. Some say foreign naval troops boarded their boats and looted their belongings. "What can you do but to let them take what they want? They have guns," says boat captain Tang Haoxin, 50. Others say they have been thrown into foreign jails. Pu, 60, says he was detained for six months in eastern Malaysia in 1989, after he was arrested for entering Malaysian waters during a fishing trip near the Spratlys.

Fishermen from other countries in the region have complained of similar harassment by the Chinese authorities. In April, China released 21 Vietnamese fishermen and their two boats after having detained them for over a month for fishing illegally in the disputed Paracels. In May, it released 14 Vietnamese fishermen after having held them for five days, but kept their boat.

Militant Chinese Fishermen in the South China Sea

Many Chinese fishermen's support their government's assertive posture against other claimants in the South China Sea. Boat captain Lu Jiabang, told the Strait Times: “"Now that our country is strong again, we should not give in to others any more. Why should we be bullied in our own territory?" In particular, locals applaud the establishment of Sansha city in the Paracels last month to administer some 2 million square-kilometers of the waters surrounding the area, the Spratlys and the Macclesfield Bank - all localities where there are overlapping claims. After all, 60 percent of the 1,000-plus Sansha residents were relocated from Tanmen. [Source: Kor Kian Beng, Straits Times, August 31, 2012]

One of them, He Shixuan, 57, moved to Sansha after a run-in with the Philippines' naval troops near Scarborough Shoal in April. "They boarded our boats, held us at gunpoint and forced us to sign confession statements that we were in Philippine waters," he recounts. "But we refused, pointed to the Chinese flag on our boat and yelled 'This is China's territory!' at them." The rising nationalism has fueled the Tanmen fishermen's resolve to press towards the troubled waters.

They are egged on by He Jianbin, who heads the state-run Baosha Fishing Corporation based on Hainan Island. He has urged the Chinese government to turn fishermen into fighters."If we put 5,000 Chinese fishing boats in the South China Sea, there will be 100,000 fishermen," he said in the nationalistic Global Times in June. "And if we make all of them militiamen, give them weapons, we will have a military force stronger than all the combined forces of all the countries in the South China Sea."

Such militant domestic pressure, which is seen in the Philippines and Vietnam too, could prevent these governments from taking any stance that could be seen as backing down from a conflict or giving in, cautions Storey. But for the fishermen of Tanmen, the war cry is in tune with their own desires. Says fisherman Li Linbo, 60: "For centuries, our ancestors fished in the South China Sea. It is our zu zong hai ("ancestral waters" in Mandarin). If we don't safeguard it, who will?"

China’s Energy Claims and the South China Sea

Pratas Island In January 2011, China’s Ministry of Land and Resources in Beijing told the People’s Daily, the Party’s official organ, that Chinese geologists had found 38 oil and gas fields under the South China Sea and would start exploiting them this year.

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, “China’s onshore oil resources have been heavily tapped since the 1960s. An expected decline in output is prompting offshore exploration and production in other locations, including the South China Sea. With consumption soaring and the price of imports rising, China is desperate for new sources to boost its proven energy reserves, which for oil now account for just 1.1 percent of the world total — a paltry share for a country that last year consumed 10.4 percent of total world oil production and 20.1 percent of all the energy consumed on the planet, according to theBP Statistical Review of World Energy. As a result, Beijing views disputed waters as not merely an arena for nationalist flag-waving but as indispensable to its future economic well-being. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, September 17 2011]

“The potential for what lies beneath the sea is clearly a big motivator in a recent shift by China to a more pugnacious posture in the South China Sea, said William J. Fallon, a retired four-star admiral who headed the U.S. Pacific Command from 2005 until 2007. China is wary of pushing its claims to the point of serious armed conflict, which would torpedo the economic growth on which the party has staked its survival. But, Fallon said, such a thick fog of secrecy surrounds China’s thinking that “we have little insight into what really makes them tick.”

In the summer of 2011 China’s largest offshore petroleum producer launched a $1 billion oil rig from Shanghai, The drilling platform, said China, would soon be heading in the general’s direction — southward into waters rich in oil and natural gas, and also in volatile fuel for potential conflict. The China National Offshore Oil Corp. (CNOOC), owner of the rig, declined to comment on the whereabouts of its drilling platform — which allows China to drill in much deeper waters than before. Reconnaissance flights by the Philippines military initially have not yet picked up any sign of it.

Tensions Over China’s Search for Oil and Gas in the South China Sea

Andrew Higgins wrote in the Washington Post, China’s insistence that it owns virtually the whole sea — and the resources beneath it — has fueled deep unease, undoing much of the goodwill China previously worked hard to develop.” Maybe they need energy more than they need their image,” said Abraham Mitra, the governor of Palawan. [Source: Andrew Higgins, Washington Post, September 17 2011]

When CNOOC launched the $1 billion oil rig, Lt. Gen. Juancho Sabban, the commander of Philippine military forces 1,500 miles away in the South China Sea, began preparing for trouble. “We started war-gaming what we could do,” said Sabban, a barrel-chested, American-trained marine who, as chief of the Philippines’ Western Command, is responsible for keeping out intruders from a wide swath of sea that Manila views as its own but that is also claimed by Beijing.

A big factor in this uncertainty is a meshing of Chinese commercial, strategic and military calculations.Like other giant energy companies in China, CNOOC, pursues profit but is ultimately answerable to the party, whose secretive Organization Department appoints its boss. When CNOOC took delivery of the new high-tech rig, Sabban took fright at Chinese reports that it would start work at an unspecified location in the South China Sea. With only a handful of aging vessels under his command but determined to block any drilling in Philippine-claimed waters, he came up with an unorthodox battle plan: He asked Filipino fishermen to be ready to use their boats to block the mammoth rig should it show up off the coast of Palawan, a Philippine island from whose capital, Puerto Princesa, the lieutenant general runs Western Command. “We can’t stand up to the military power of China, but we can still resist,” Sabban said. “We have to send a message that we will defend our territory.”

Chinese Politics and Underwater Exploration in the South China Sea

Antelope Reef In 2004, China, Vietnam and the Philippines signed an agreement to carry out join oil exploration. China has mainly used the agreement to explore areas on other country’s continental shelves. In the summer of 2010, a Chinese submersible set a record by diving more then three kilometers to the bottom of the South China Sea and planting a flag there. The effort was seen as much as gesture of its claim on the maritime region as it was an achievement in underwater exploration. [Source: William J. Broad, New York Times, September 11, 2010]

William J. Broad wrote in New York Times.” When three Chinese scientists plunged to the bottom of the South China Sea in a tiny submarine early this summer, they did more than simply plant their nation flag on the dark seabed. The Jiaolong submersible planted a Chinese flag on the bottom of the South China Sea The men, who descended more than two miles in a craft the size of a small truck, also signaled Beijing intention to take the lead in exploring remote and inaccessible parts of the ocean floor, which are rich in oil, minerals and other resources that the Chinese would like to mine. And many of those resources happen to lie in areas where China has clashed repeatedly with its neighbors over territorial claims.”

Liu Feng, director of the dives, was quoted as saying by China Daily, as saying, “The global seabed is littered with what experts say is trillions of dollars’ worth of mineral nodules as well as many objects of intelligence value: undersea cables carrying diplomatic communications, lost nuclear arms, sunken submarines and hundreds of warheads left over from missile tests. While a single small craft cannot reel in all these treasures, it does put China in an excellent position to go after them.”

United States and the Spratly Islands

The conflict could draw in the United States, which worries that the disputes could hurt access to one of the world's busiest sea lanes The United States has said it takes no sides in the territorial spats but that it considers ensuring safe maritime traffic in the waters to be in its national interest It has backed a call for a "code of conduct" to prevent clashes in the disputed territories. US Secretary of State Hillary Rodham Clinton said that the peaceful resolution of disputes over the Spratly and Paracel island chains was in the American national interest. The Philippines and Vietnam have sought the backing of the U.S., which said it wants to keep international maritime traffic free from interference. China has accused the U.S. of stoking tensions in the region by holding naval drills in the contested waters.

Edward Wong wrote in the New York Times, “In 2009, two American warships were involved in prominent incidents in which the Chinese Navy appeared to be working closely with civilian law enforcement vessels and fishing trawlers, Pentagon officials said. On March 4, the Victorious, an American ship, was illuminated with a spotlight by a fisheries patrol vessel in the Yellow Sea. The next day, 12 maritime surveillance aircraft did flybys of the Victorious. Four days later, the Impeccable, an American ship surveying off the south coast of China, was “harassed” by five Chinese vessels — four of them civilian ships, the Pentagon said. In these encounters, Mr. Blasko said, “Beijing demonstrated its will to employ military and civilian capabilities to protect what it considers its sovereignty.” [Source: Edward Wong, New York Times, October 5, 2010]

The United States called on China to ease up and called for freedom of navigation in the South China Sea. Complicating the issue is the role the United States wants to play in resolving the dispute. It is a key Philippine defense treaty partner, which means that in case of Chinese attack it is obligated to come to Manila’s aid.

In an apparent reference to U.S. meddling in the South China Sea, China’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Jiang Yu said, “We are resolutely opposed to countries not involved interfering...and we oppose the internationalization of the South China Sea dispute because it only make the issue more complicated.” In response to this Washington said it would support other Southeast Asian countries at an ASEAN meeting and said free navigation in the area was a U.S. “national interest” and called for a “code of conduct” be established for “legitimate claims in the South China Sea.”

In July 2011 U.S. Secretary of State Hillary Clinton and Chinese Foreign Minister Yang Jiechi, met at Asia's biggest security conference, appeared eager to ensure the South China Sea dispute did not become another source of friction between the two countries. "I want to commend China and ASEAN for working so closely together to include implementation guidelines for the declaration of conduct in the South China Sea," Clinton said at the meeting on the Indonesian resort island of Bali. [Source: Reuters, July 22, 2011]

At the Bali meeting Clinton called on rivals in the disputed South China Sea to back up territorial claims with legal evidence — a challenge to China's declaration of sovereignty over vast stretches of the region. "We also call on all parties to clarify their claims in the South China Sea in terms consistent with customary international law...Claims to maritime space in the South China Sea should be derived solely from legitimate claims to land features.”

China Media Tell U.S. to "Shut Up" over South China Sea Tensions

According to a Reuters report: The stakes have risen in South China Sea as the U.S. military shifts its attention and resources back to Asia, emboldening its long-time ally the Philippines and former foe Vietnam to take a bolder stance against Beijing. The United States has stressed it is neutral in the long-running maritime dispute, despite offering to help boost the Philippines' decrepit military forces. It says freedom of navigation is its main concern about a waterway that carries $5 trillion in trade -- half the world's shipping tonnage. [Source: Reuters, August 5, 2012]

In August 2012, Reuters reported: “China's state-run media ramped up condemnation of the United States over tensions in the South China Sea, with the Communist Party's top newspaper telling Washington to "Shut up" and charging it with "fanning flames" of division in the region. The Chinese Foreign Ministry's condemned a U.S. State Department statement that said Washington was closely monitoring territorial disputes in the South China Sea, and that China's establishment of a military garrison for the area risks "further escalating tensions in the region". [Source: Reuters, August 6, 2012]

Beijing has said its disputes with Vietnam, the Philippines and other southeast Asian claimants should be settled one-on-one, and it has bristled at U.S. backing for a multilateral approach to solving the overlapping claims. "We are entirely entitled to shout at the United States, 'Shut up'. How can meddling by other countries be tolerated in matters that are within the scope of Chinese sovereignty?," said a commentary in the overseas edition of the People's Daily, an offshoot of the ruling Chinese Communist Party's top newspaper.

The main, domestic edition of the newspaper was equally harsh, and accused Washington of seeking to open up divisions between China and its Asian neighbors. "Fanning the flames and provoking division, deliberately creating antagonism with China, is not a new game," said a commentary in the People's Daily domestic edition. "But of late Washington has been itching to use this trick."

The ire from Beijing shows the potential for tensions over the South China to fester into a wider diplomatic quarrel, even outright military confrontation remains unlikely. A week before, the People's Daily said China's "core interests" were at stake in its territorial claims across the South China Sea -- language that puts such claims on a similar footing with China's claims of indisputable sovereignty over Tibet and Xinjiang in its west.

Solutions to the South China Sea Dispute

Gareth Evans wrote in Project Syndicate: “A sensible way forward would begin with everyone staying calm about China's external provocations and internal nationalist drumbeating. There does not appear to be any alarmingly maximalist, monolithic position, embraced by the entire government and Communist Party, on which China is determined to steam ahead. Rather, according to an excellent report released in April by the International Crisis Group, its activities in the South China Sea over the last three years seem to have emerged from uncoordinated initiatives by various domestic actors, including local governments, law-enforcement agencies, state-owned energy companies, and the People's Liberation Army. [Source: Gareth Evans, Project Syndicate, Christian Science Monitor, July 30, 2012. Evans was Foreign Minister of Australia from 1988-1996 and is President Emeritus of the International Crisis Group.

China's -foreign ministry understands the international-law constraints better than most, without having done anything so far to impose them. But, for all the recent PLA and other activity, when the country's leadership transition (which has made many key central officials nervous) is completed at the end of this year, there is reason to hope that a more restrained Chinese position will be articulated.

China can and should lower the temperature by re-embracing the modest set of risk-reduction and confidence-building measures that it agreed with Asean in 2002 - and building upon them in a new, multilateral code of conduct. And, sooner rather than later, it needs to define precisely, and with reference to understood and accepted principles, what its claims actually are. Only then can any credence be given to its stated position - not unattractive in principle - in favour of resource-sharing arrangements for disputed territory pending final resolution of competing claims.

The US, for its part, while justified in joining the Asean claimants in pushing back against Chinese overreach in 2010-2011, must be careful about escalating its rhetoric. America's military 'pivot' to Asia has left Chinese sensitivities a little raw, and nationalist sentiment is more difficult to contain in a period of leadership transition. In any event, America's stated concern about freedom of navigation in these waters has always seemed a little overdrawn.

One positive, and universally welcomed, step that the US could take would be finally to ratify the Law of the Sea Convention, whose principles must be the foundation for peaceful resource sharing - in the South China Sea as elsewhere. Demanding that others do as one says is never as productive as asking them to do as one does.

Image Sources: Wikicommons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, Yomiuri Shimbun, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2012