TEA CULTIVATION

Two leaf and a bud,

Sylhet, Bangladesh

There are two main varieties of tea plant: the small-leafed China plant and the large-leafed Assam variety, discovered on the Burma-India border in 1824. There is also a Cambodian variety used mostly in hybrids. The Chinese type — Camellia sinensis var. sinensis, — is multiple-stem shrub with small leaves. It is long-lived and can withstand cold weather. The Indian type — Camellia sinensis var. assamica — is a single-stem plant with larger, softer leaves — more like a tree if left unpruned. It is more delicate, shorter-lived, and best grown in subtropical and rainy regions. [Source: Fowler Museum at UCLA]

Tea grows best in misty, rainy regions at altitudes of 2,000 to 7,000 feet in the tropics and lower elevations in temperate regions.. The best tea is produced in regions that have dry days and cool nights. Slow growth under some stress brings out the best flavor in tea but yields are lower under these conditions. Tea bushes are pruned to about one meter in height so they can be easily plucked. If left unattended they would grow into 12-meter-high trees. The bushes produce a white flower and a hazelnut-size fruit with three compartments, each with a seed. In many cases these are not allowed to develop. The leaves of the plant are what produces tea. The tea flavor is produces by oils in the leaves

Tea requires year round maintenance. Every one to five years the plants are trimmed from waist to knee height to keep them from growing into trees and prevent the branches from extending too far sideways. Seasonal pickings keep the bushes trimmed like a hedge.

The waist-high bushes at a typical tea plantation are often 25 to 90 years old. Tea growers are now experimented with new strains such TV29 that produce as many more quality leaves than present bushes.

See Separate Article TEA: ITS HISTORY, HEALTH AND DIFFERENT KINDS OF TEA factsanddetails.com ; TEA IN CHINA: HISTORY, BUSINESS AND CONNOISSEURS factsanddetails.com ; KINDS OF CHINESE TEA factsanddetails.com ;TEA DRINKING AND CULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ;TEA AGRICULTURE IN CHINA factsanddetails.com ; TEA IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

Good Websites and Sources: Book: "All the Tea in China" by Kit Chow and Ione Kramer; Wikipedia article on History of Tea in China Wikipedia ; Rare Teas holymtn.com ; Tea Culture index-china-food.com ; Asia Recipe asiarecipe.com ; 19th Century Tea Trade in China Harvard Business School

Tea Agriculture

Much of the world's tea is harvested on plantations called "estates" or "gardens." Many of these have ski-tow-like ropeways and chutes that are used to carry leaves to where the leaves are processed. The tea industry is a labor-intensive business driven by thousands of peasants who pluck and dry the leaves are paid very little — often less than $1 a day — but usually live in free housing in crude dormitories on the estate where they work, and they are given free medical care and education. .

Tea bushes are grown from cuttings or seeds. They take about four years to mature. When they are six to 18 months old they are planted in a the plantation and when they get a little bigger they replanted into their permanent spot in a row at the plantation about four feet apart. About 3,000 plants grow in hectare of land.

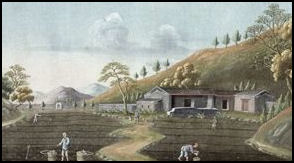

Tea grows best on sloping terrain. Tea plants on mountains and hills rest on carefully constructed terraces that trap water and prevent erosion. Sometimes trees are planted for shade and windbreaks. Plants grow in low regions are ready to harvest after three years. Plants grow in high regions are ready to harvest after five years.

Tea Harvesting

Tea plantation in India

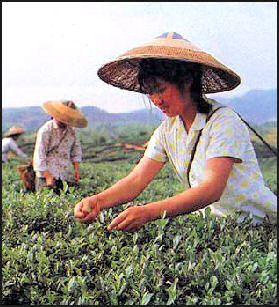

Tea is almost exclusively hand picked. In most parts of the world the work is done by women. Tea leaves have to be picked carefully. If they are too big they are too tough; if they are too small they are not economically viable

The tea pickers pluck new and tender "flush" (two leaves and a bud). These flushes appear every seven or eight days in hot climates and around twice that long in cooler climates. Generally the buds near the end of a branch are considered to be the best quality. Lower quality ones are found further down the branch. The flushes are flung over the shoulder of the pickers into baskets strapped onto their heads and backs. Good pickers pick around 72 kilograms (160 pounds) of leaves a day, from which about 18 kilograms (40 pounds) of finished tea is made.

Freshly picked leaves weigh about twice as much as correctly dried tea leaves. Skill and experience are needed to accurately judge their condition. It is difficult to produce a high quality tea. Some that do pick just one bud and two leaves from a single twig (many companies remove more leaves to increase production) and pick the leaves between 9:00am and 3:00pm when the leaves are in the best condition.

Tea Processing

Most tea is processed in large multistory buildings that often look like giant wooden sheds. The tea is often brought in by trucks, moved through the factory on conveyor belts and elevators. A factory may process 20,000 kilograms of leaves a day in the high season. This yields 5,000 kilograms of tea. The final product is placed in large bags that are moved by truck, train or ship.

Green tea is put in a "steamer" and heated immediately after it is picked. This softens the tea for rolling. The tea is not fermented. The leaves are rolled and dried. Leaves that are made into black tea are “withered” (de-moisturized by blowing air through them) in a withering shed or upper story of the factory. Here, piles of leaves are set on hessian mat, nylon "tats," and withered by duct-blown hot air created by large machines with large fans and heaters. Withering removes moisture while leaving the leaves soft and pliable.

Next the tea is rolled in special machinery rather than crushed so that they aromatic oils that flavor tea are not destroyed. While being rolled the juice oozes for tea leaves and fermentation begins. After rolling the tea is fermented more by placing in a cool, moist room to accelerate oxidation, in the process turning the tea from green to bright copper. The length of their fermentation process determines how much oxidation takes place, which in turn determines whether the tea is green, black or oolong or another variety.

During the next stage the tea is dried or “fired” for 15 to 25 minutes. For black teas, the copper leaf turns black as carefully controlled driers reduce water content to 3 percent. The key — and the tricky part — to producing good tea is stopping fermentation and cutting off oxidation at precisely the right time. Finally, the “made tea” is sorted and rated into commercial grades, ready for shipment. The grades are determined both by size and quality and the elevation they are grown. Different sizes are sorted using machines with trays that shake the tea.

Tea Tasters

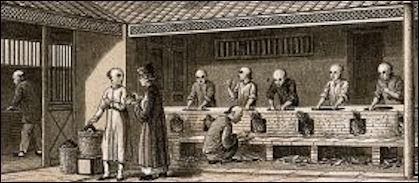

tea tasters

Companies often how their teas will be blended and how much they will offer growers for their products based on the work of tea tasters sample up to 200 cups a day of tea to gauge their quality. Each cup is made with 6.5 grams of the sample tea steeped for exactly six minutes with freshly boiled filtered water, plush two teaspoons of fresh, TTB-tested milk and no sugar (the British way of drinking tea) and tea is judged by taste, color and aroma. Sometimes three grams steeped for three minutes in 100̊C water

The cups are usually lined up in a row. The tea tasters don't drink the samples but taste and test them by making loud slurping noises as they slosh them around in their mouth, finally spitting the samples into enamel spittoons that they roll along with them. To fully enjoy the flavor of a brew, tea tasters recommend that you slurp it.

Buyers and tasters refer to different kinds as tea as bright, strong and thick (good), chesty (meaning it tastes like plywood), and cheesy (the worst). Pinty, pungent, meaty, body and bakery are all terms used to describe taste. Coppery, dull and bright describe color. A medium grade tea might be described as "alpha, little flaky, thick, bright, rupees 2.20.”

Based on decisions form the tea tasters, teas are blended in different varieties and generally sold in bags or loose leaves Tea quality and taste are influenced by blending, cultivation techniques, soil quality, altitude, rain, sun, plucking, weather during the growing season and care taken during processing and shipping, among other things. According to one expert Americans prefer "pointy," light flavored high altitude teas while English like "thick" teas.

Tea Production

Tea is usually at auctions in the country of origin or at commodity markets in Europe or the United States and simple sold in deals made between producers and buyers. In the old days tea was sold in chests and buyers drilled holes in the chests to sample the quality.

The tea industry has suffered as a result of global competition, fickle consumer tastes and labor disputes.

In 1998, a glut of tea from low-cost producers caused prices and profits to dive. Some estates suffered labor problems or sold their tea at below cost prices. Others went bankrupt or abandoned their operations.

Kenya and Sri Lanka are now the world’s largest tea exporters, each sold 314 million kilograms on 2006, ahead of India, which sold 204 million kilograms. In 2008 Kenya was the leading tea exporter.

Tea production costs: 1) India ($1.62); 2) Sri Lanka ($1.16); 3) Kenya and Malawi ($0.84). Costs are higher in India in part because of laws that estates must provide workers with education and medical care and drinking water.

In 2010, prices reached a record $3.97 a kilogram in part because a drought in Kenya that was devastating to tea crops there.

Fair-Trade Tea

The fair trade tea movement, which has grown considerably over the last few decades, reflects an attempt to address some of the inequities that tea-producing countries experience by setting up and monitoring fair labor practices, health and living conditions, and environmental standards on the plantations. While the work of fair trade institutions is worthy of praise, critics contend that it caters mostly to large plantation owners — ironically subsidizing a dysfunctional structure left over from exploitative colonial practices — and that it fails to address the needs of small-scale growers, who are increasingly being marginalized by the global economy. Others note that it is too easy to acquire the status of.fair trade retailer. by adding just a few fair trade teas to the general catalog and that some retailers take advantage of this, motivated by the desire to capture the fair trade market and not by a true respect for ethical practices. [Source: Fowler Museum at UCLA]

Tea planting

Clearly, more work needs to be done to create satisfactory living and working conditions for the workers who produce the tea we enjoy; to build market access for small- and medium-scale tea growers and make the certification system accessible to them; to encourage the development of cooperatives among small farmers working in remote areas without infrastructure; and, last but not least, to develop and enforce regulations for truly sustainable environmental practices in order for nature‘s cycles to be preserved and respected instead of exploited and drained.

Parminder Bahra wrote in Times of London, “In the tea market, Fairtrade is taking on an industry that for decades has been accused of exploiting its workers. The task is complicated because most workers are hired by tea estates that have hardly changed in a century. Estates are run as small kingdoms, with worker’s accommodation supplied by the company...In tea estates, the premium is initially held by the estate owners. Under Fairtrade rules, the estates must set up a joint body of managers and workers who decide how the premium is spent. In many instances that does not happen.”

The system works much better with coffee. Bahra wrote in Times of London, “In the coffee industry, the relationship between the farmer or worker, and the premium is much closer. Fair-trade certifies only small-scale farmers (or co-cooperatives) and the Fairtrade premium paid by coffee buyers goes directly to the farmers or cooperative.

In the tea industry Bahra wrote, “Inspections are vital to ensure that poor practices are tallied, but there remains a nagging doubt as to whether they are sufficiently robust when the labeling scheme, standards and inspections are all run by the same organization. Fairtrade admits that some workers have not heard of Fairtrade but argues that it takes time to educate and involve the workers. But consumers have a right to known that there are problems in the tea industry and that the situation is not as rosy as some of the marketing suggests.”

Workers at Fair-Trade-Certified Tea Plantations

Fairtrade tea

Dunsandle is a tea estate in the Niligiri Hills of south-central India that been received Fairtrade certification since 2000. Workers at the estate that talked to the Times of London were quick to criticize the designation or had never heard of it. One said, “No matter what the propaganda [related to Fair-trade] is in Europe, nothing is being done here to help us.” Another said, “If there is extra money, we have no idea what is happening to it. We requested help to buy gas or a bus to take the children to school. There was talk of a community center being built, but nothing has happened.” One of the problems with Dunsandle is that only a small percentage of the tea sold by the estate is Fairtrade.” The workers earn a basic wage of $1.76 a day. Much of the money from the Fairtrade premiums have gone into a retirement bond scheme that its beneficiaries don’t understand.

Kitumbe is a Fair-trade-certified tea estate, owned by the international tea conglomerate Finlay’s, near the Great Rift Valley in Kenya. Workers there live three or four to a room in one room shacks with leaky roofs. The Times of London reported managers at the estate were given ample warning that the FLO inspectors were coming. Before they arrived huts were painted and workers were coached what t say. A report by Kenya Human Rights said that sexual harassment and the mistreatment of workers was common at tea estates owned by Finlay’s. The organization said workers were often hired based on their ethnicity and hosting was ‘deplorable.’ There, workers are paid about 42 cents a day.

World’s Top Tea Producing Countries

World’s Top Producers of Tea (2020): 1) China: 2970000 tonnes; 2) India: 1424662 tonnes; 3) Kenya: 569500 tonnes; 4) Argentina: 335225 tonnes; 5) Sri Lanka: 278489 tonnes; 6) Turkey: 255183 tonnes; 7) Vietnam: 240493 tonnes; 8) Indonesia: 138323 tonnes; 9) Myanmar: 126486 tonnes; 10) Thailand: 97697 tonnes; 11) Bangladesh: 89931 tonnes; 12) Iran: 84683 tonnes; 13) Japan: 69800 tonnes; 14) Uganda: 63411 tonnes; 15) Malawi: 47865 tonnes; 16) Tanzania: 46058 tonnes; 17) Rwanda: 33645 tonnes; 18) Mozambique: 33592 tonnes; 19) Nepal: 24270 tonnes; 20) Burundi: 16337 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org. A tonne (or metric ton) is a metric unit of mass equivalent to 1,000 kilograms (kgs) or 2,204.6 pounds (lbs). A ton is an imperial unit of mass equivalent to 1,016.047 kg or 2,240 lbs.]

Tea picking

World’s Top Producers (in terms of value) of Tea (2019): 1) China: Int.$5358728,000 ; 2) India: Int.$2682219,000 ; 3) Kenya: Int.$885371,000 ; 4) Sri Lanka: Int.$579095,000 ; 5) Vietnam: Int.$519589,000 ; 6) Turkey: Int.$503611,000 ; 7) Indonesia: Int.$265897,000 ; 8) Myanmar: Int.$255653,000 ; 9) Iran: Int.$175264,000 ; 10) Bangladesh: Int.$174981,000 ; 11) Argentina: Int.$165420,000 ; 12) Japan: Int.$157644,000 ; 13) Uganda: Int.$141794,000 ; 14) Tanzania: Int.$121762,000 ; 15) Thailand: Int.$113463,000 ; 16) Malawi: Int.$95678,000 ; 17) Mozambique: Int.$66000,000 ; 18) Rwanda: Int.$60852,000 ; 19) Nepal: Int.$48636,000 ; [An international dollar (Int.$) buys a comparable amount of goods in the cited country that a U.S. dollar would buy in the United States.]

Top Tea Producing Countries in 2008: (Production, $1000; Production, metric tons, FAO): 1) China, 1380615 , 1275384; 2) India, 871615 , 805180; 3) Kenya, 374331 , 345800; 4) Sri Lanka, 344995 , 318700; 5) Turkey, 214386 , 198046; 6) Vietnam, 189331 , 174900; 7) Indonesia, 163297 , 150851; 8) Japan, 104462 , 96500; 9) Argentina, 82270 , 76000; 10) Thailand, 66636 , 61557; 11) Bangladesh, 63868 , 59000; 12) Malawi, 52112 , 48140; 13) Uganda, 46340 , 42808; 14) Iran (Islamic Republic of), 45842 , 42348; 15) United Republic of Tanzania, 37671 , 34800; 16) Myanmar, 28686 , 26500; 17) Zimbabwe, 24139 , 22300; 18) Rwanda, 21612 , 19965; 19) Mozambique, 18257 , 16866; 20) Nepal, 17493 , 16160

World’s Top Tea Exporting Countries

World’s Top Exporters of Tea (2020): 1) Kenya: 575509 tonnes; 2) China: 348815 tonnes; 3) Sri Lanka: 285087 tonnes; 4) India: 210486 tonnes; 5) Vietnam: 126450 tonnes; 6) Uganda: 72454 tonnes; 7) Argentina: 65978 tonnes; 8) United Arab Emirates: 57720 tonnes; 9) Malawi: 46923 tonnes; 10) Indonesia: 45265 tonnes; 11) Poland: 24262 tonnes; 12) Germany: 22111 tonnes; 13) Russia: 20538 tonnes; 14) United Kingdom: 19087 tonnes; 15) Tanzania: 18879 tonnes; 16) Rwanda: 15309 tonnes; 17) Netherlands: 14338 tonnes; 18) United States: 14262 tonnes; 19) Nepal: 13570 tonnes; 20) Zimbabwe: 12138 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Tea (2020): 1) China: US$2037982,000; 2) Sri Lanka: US$1329509,000; 3) Kenya: US$1224063,000; 4) India: US$692074,000; 5) United Arab Emirates: US$315633,000; 6) Poland: US$264869,000; 7) Germany: US$226462,000; 8) Vietnam: US$198926,000; 9) Japan: US$154401,000; 10) United Kingdom: US$136347,000; 11) Netherlands: US$114363,000; 12) Russia: US$105418,000; 13) Taiwan: US$100346,000; 14) Indonesia: US$96325,000; 15) United States: US$88717,000; 16) Uganda: US$78672,000; 17) Argentina: US$75365,000; 18) Malawi: US$74449,000; 19) France: US$52988,000; 20) Belgium: US$48040,000

Malaysia tea plantation

World’s Top Exporters of Tea, Maté Extracts (2020): 1) Spain: 93205 tonnes; 2) Canada: 55107 tonnes; 3) United States: 19238 tonnes; 4) Germany: 12339 tonnes; 5) China: 12322 tonnes; 6) United Kingdom: 10136 tonnes; 7) Malaysia: 9897 tonnes; 8) Thailand: 8558 tonnes; 9) India: 7294 tonnes; 10) Netherlands: 5864 tonnes; 11) Ireland: 4704 tonnes; 12) Poland: 4686 tonnes; 13) France: 4581 tonnes; 14) Jordan: 3863 tonnes; 15) Kenya: 3309 tonnes; 16) Sri Lanka: 3146 tonnes; 17) Chile: 2893 tonnes; 18) Argentina: 2826 tonnes; 19) Greece: 2374 tonnes; 20) Philippines: 2026 tonnes

World’s Top Exporters (in value terms) of Tea, Maté Extracts (2020): 1) United States: US$166318,000; 2) Netherlands: US$151287,000; 3) China: US$130871,000; 4) Ireland: US$90095,000; 5) Germany: US$77378,000; 6) United Kingdom: US$71313,000; 7) Canada: US$62687,000; 8) India: US$54463,000; 9) Spain: US$47885,000; 10) Malaysia: US$33829,000; 11) Thailand: US$32517,000; 12) Sri Lanka: US$24609,000; 13) Japan: US$22587,000; 14) Chile: US$18475,000; 15) Singapore: US$17145,000; 16) Kenya: US$16795,000; 17) France: US$15403,000; 18) Jordan: US$15202,000; 19) Italy: US$11360,000; 20) South Korea: US$11307,000

World’s Top Tea Importing Countries

World’s Top Importers of Tea (2020): 1) Pakistan: 254406 tonnes; 2) Russia: 151441 tonnes; 3) United Kingdom: 129865 tonnes; 4) United States: 107414 tonnes; 5) Egypt: 74695 tonnes; 6) United Arab Emirates: 74417 tonnes; 7) Morocco: 71535 tonnes; 8) Iran: 63286 tonnes; 9) Iraq: 54930 tonnes; 10) China: 43343 tonnes; 11) Poland: 42356 tonnes; 12) Saudi Arabia: 41945 tonnes; 13) Germany: 41759 tonnes; 14) India: 33184 tonnes; 15) Uzbekistan: 31426 tonnes; 16) Taiwan: 30569 tonnes; 17) Kazakhstan: 29251 tonnes; 18) Japan: 27476 tonnes; 19) Malaysia: 27300 tonnes; 20) South Africa: 23308 tonnes. [Source: FAOSTAT, Food and Agriculture Organization (U.N.), fao.org]

World’s Top Importers (in value terms) of Tea (2020): 1) Pakistan: US$589756,000; 2) United States: US$473832,000; 3) Russia: US$412245,000; 4) United Kingdom: US$349763,000; 5) Iran: US$277026,000; 6) Saudi Arabia: US$243557,000; 7) Hong Kong: US$221816,000; 8) Morocco: US$202682,000; 9) Germany: US$197742,000; 10) Egypt: US$197215,000; 11) United Arab Emirates: US$194431,000; 12) Iraq: US$181338,000; 13) China: US$180014,000; 14) France: US$167708,000; 15) Netherlands: US$157682,000; 16) Japan: US$156431,000; 17) Poland: US$131628,000; 18) Canada: US$123672,000; 19) Australia: US$105951,000; 20) Kazakhstan: US$101237,000

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons; University of Washington, Nolls China website http://www.paulnoll.com/China/index.html , Beifan.com; Weird Meat; All Posters com Search Chinese Art

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, Lonely Planet Guides, Compton’s Encyclopedia and various books and other publications.

Last updated March 2022