ALCOHOLIC DRINKS IN ASIA

About half of all Asians lack an active enzyme which breaks down acetaldehyde, a toxic chemical derived from ethanol found in most forms of alcohol. As a result, when they drink they often get sick to their stomach or turn red in the face. Most westerners have this enzyme, and consequently they need to drink much more to get drunk or turn red. Some Asians turn bright red after only a few sips of alcohol. If they continue drinking they often vomit because their bodies reject the alcohol.

Beer for the most part was introduced by the colonial powers, who introduced their regional tastes, and some were adapted for local preferences. There are some interesting Asian beers. In the Himalayan kingdom of Bhutan, the Bumthang Brewery makes an unfiltered wheat beer called Red Panda. At the Archipelago Brewery in Singapore, expatriate American brewer Fal Allen uses lemon grass, Chinese orange peel and ginger in his recipes.

Scotch is very popular in Asia, where it is regarded as a prestige drink. In 1994, sales rose by 35 percent in Thailand, by 48 percent in South Korea and by 83 percent in Taiwan.

Asia Overtakes Europe in Beer Consumption

According to Kirin Asia overtook Europe as the No.1 beer producer in 2009 when it produced 58.67 million kiloliters of brew. In the previous year beer production in Europe shrunk 5.1 percent to 55.15 million kiloliters. Almost all beer is consumed where it is made, so Asians collectively drink more beer than the people of any other continent.

In August 2010 The Economist reported: “That would seem like encouraging news for the world's big four brewers — Anheuser-Busch InBev (ABI), SABMiller, Carlsberg and Heineken — which between them supply nearly half the needs of the world's beer drinkers. But unlike America and other hugely profitable mature markets where beer drinking has levelled off or is in decline, China’s drinkers provide slender profits. Still it remains a market with huge potential, though foreign brewers must now be rather tired of hearing that. [Source: The Economist and The Economist online, August 17, 21 2010]

”All four have pursued roughly the same strategy in recent years. They bought breweries in rich countries, where beer drinking has levelled off or fallen, and boosted profitability by stripping out costs. At the same time they snapped up brewers in emerging markets, where the party can only get livelier. But they cannot afford yet to relax with a cool one. Most tasty takeover targets have been swallowed, so the brewing giants will henceforth have to rely more on organic growth. Asia's spectacular thirst ought to help a lot, but won't yet.

”Consider China, which has come from nowhere a few decades ago to become the world's biggest quaffer of beer by far. Its people slosh down 70 percent more than Americans do, and the market is growing by nearly 10 percent a year (a bit better than America's 1.2 percent). But profits are slim. ABI's results for the first half of this year show margins of 41 percent in America but only 14 percent in China and South Korea. And China's market is highly fragmented — the top two brewers have only 35 percent of it, compared with 70-100 percent in some countries. This means that retailers have brewers over a barrel.

”Buy a brewer in a poor country and you get a familiar brand and a ready-built distribution network. As incomes rise, the locals may be lured into drinking more profitable premium beers. Alas for the big brewers, this is not yet happening in China, and may not for a generation, says Anthony Bucalo of Credit Suisse, a bank. Other Asian markets are tiny, apart from Japan. But western brewers have never been able to compete with Japanese ones on their home turf. And takeovers are unthinkable given the country's ice-cold attitude to foreign ownership. Some day, billions of thirsty Asians will make global brewers sing. But not today.

Beer and Asian Food

Beer columnist Greg Kitsock wrote in the Washington Post, “Don't hand me a wine list when I'm dining on Sichuan or Indian or Thai cuisine. For me, wine tends to lock in the heat of the heavily seasoned dishes of South and East Asia and fares poorly itself. "Spices distort wine flavors, turning white wines hot and red wines bitter," writes Garrett Oliver in his book "The Brewmaster's Table."[Source: Greg Kitsock, Washington Post, August 13, 2008]

”But beer works hand in glove with those cuisines. "Curry's main ingredients -- garlic, chilies, lemon grass, coriander, turmeric, cinnamon, ginger -- all those warming spices meld wonderfully with the toasty flavors of malted barley," says Lucy Saunders, author of "The Best of American Beer & Food" and a contributing writer to Asian Restaurant News. "The richness of coconut milk and palm oil can't knock out the crisp texture of carbonation. . . . Plus, a beer is often served chilled, which in itself is a refreshing contrast."

India pale ale was originally brewed for export to India and is not a native Indian style. It has higher alcohol content and extra hopping to help it stand up to Indian curries and chutneys. German hefeweizen, with its fruity flavors and lively carbonation, pairs well with Chinese food. It refreshes the palate like a mini-dish of sherbet, recalibrating your taste buds for the next course. Try it with a pu-pu platter or when you're sharing dishes with a party of friends.

Coriander is a spice native to the Mediterranean that has worked its way into Asian cooking. It's also an integral ingredient, along with crushed orange peel, in Belgian-style witbiers. Hitachino Nest White Ale, from a Japanese sake maker that branched into microbrewing, contains orange juice and nutmeg in addition to the traditional ingredients. Witbier complements many seafood dishes, including various sushi. If you're a fan of wasabi horseradish, you might choose a more aggressive version of the style, such as Southampton Double White Ale (6.8 percent alcohol by volume) from Southampton Ales & Lagers in Southampton, N.Y.

Asian Beers Produced in North America

Kitsock wrote that imported beers sold at Asian restaurants “are usually slight variations on the ubiquitous European pilsner style. Indeed, some are actually made in North America for the U.S. market. Read the fine print on the label: The Kingfisher served in Indian restaurants is brewed by Olde Saratoga Brewing in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. The Japanese import Kirin comes from the Anheuser-Busch plant in Los Angeles. Two other Japanese brands, Sapporo Reserve and Asahi Super Dry, are made in Canada. [Source: Greg Kitsock, Washington Post, August 13, 2008]

Brewing a beer here under license does guarantee a fresher product. The Tsingtao from China and the Singha from Thailand often have a slightly cardboardy taste from oxidation that takes place on the long boat ride over here. (Singha, hoppier and stronger, has fared better than most imports, although its Boon Rawd Brewery last year reduced the alcohol content from 6 percent to a more common 5 percent.)

Toddies

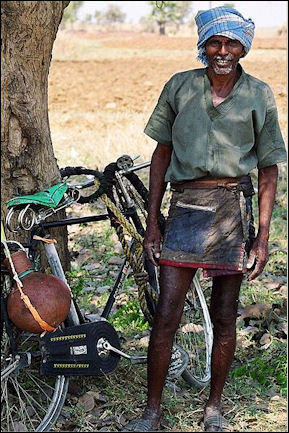

Toddy tapper Toddies and hot toddies are rich and refreshing drinks made with sweet sap tapped straight from the stems and flowers of a mature toddy palms. The sap can be drunk fresh or it can be boiled down to form a kind of brown sugar called jaggery, a key ingredient in many Southeast and South Asian sweets. The "hot toddy" originally came from Burma.

Toddy liquid left to ferment for a several hours becomes toddy wine, which sells for about 25 cents a bottle and according to some tastes like Milk of Magnesia. It takes two bottles to get a decent buzz. These have to be consumed more or less right after they are purchased, after several hours toddy wine turns to sour toddy mush.

Palm wine — which in turn can be distilled into a potent spirit widely consumed in West Africa, Sri Lanka, India and Southeast Asia — comes from a palm tree as toddy. Toddy trees are prevented from bearing fruit by binding the open flowers and bending them over. The sap is extracted initially after three weeks and collected every month or so. A good toddy tree can yield 270 liters of sap a year.

Toddy Tappers

Toddy sap is collected once every three weeks or so by agile toddy tappers who climb the trees to collect the sap and sometimes move from tree to tree on lines like tight rope walkers, using a pair of ropes — one to walk on and the other to hold with their hands for balance. The work has traditionally been each morning at dawn A single tree may produce up to two liter each time it is collected.

To begin the tapping process a toddy tapper climbs a tree and beats the round fruit on the tree with a stick and later takes in stems and flowers of the tree to withdraw the sap. After that toddy tappers go from flower to flower every morning and evening with little pots.

Typically toddy tappers climb their trees with pot in the evening, tapping the tree overnight, and collect the pot the next day in a process not unlike collecting maple syrup, earning about $3.00 a day from collecting the tap from 16 trees. A good tapper can get a month's worth of sap from one flower. After the sap is collected it is boiled until it thickens and crystallizes into golf-ball-size lumps. Yeast is added to make inexpensive wine that is ready in a few hours to drink.

Tea

Tea is the most popular drink in the world after water. A lot more people drink it than coffee, especially in China, India, Japan, Britain, Russia, Turkey and other countries in Asia, eastern Europe and the Middle East.

Tea is a drink made with the leaves of Camelia sinensis, a plant indigenous to China. The word "tea" comes from the Xiamen area of China. Tea is one of the first known stimulants. The legendary Chinese emperor Shen Nung reportedly wrote in his medical diary in 2737 B.C. that tea not only "quenches thirst" but also "lessens the desire to sleep." According to legend Shen-Nung discovered the drink when some tea leaves from a bush accidently fell into some water he was boiling to stay healthy. He liked the taste and tea was born.

According to another legend tea was created by an Indian monk with bushy eyebrows named Bodhidharma, who mediated for nine years by staring at the wall of a cave. To battle his occasional bouts of drowsiness, he came up with a novel idea — cutting off his eyelids so his eyes wouldn't close. On the place where he placed his severed eyelids, the first tea bushes appeared.

Tea contains caffeine but significantly less than coffee. A typical cup of tea-bag-brewed tea contains 40 millimeters of caffeine, compared to 100 millimeters for a typical cup of brewed coffee. The caffeine content of tea can range from 20 to 90 milligrams per cup depending on the blend of tea leaves, method of preparation and length of brewing time. Contrary to myth, green tea contains about the same amount of caffeine as black teas.

Tea has is the most popular drink in many parts of Asia. Asians love to drink tea and drink tremendous amounts of it. Prices range from a 50 cents per kilo for common teas to $730 per kilo for the rarest varieties. Tea has traditionally been served as alternative to water. It is safer than tap water or river water because at least the water was boiled.

Many people drink tea in a bowl without a handle. Throughout China you will see people on the go with thermoses and water bottles with leafy, unstrained tea, which is consumed all day long. Hot tea is usually served plain, or with sugar or milk. Chinese tea often has a lot of stuff floating in it. Jasmine tea one Washington Post reporter commented “has so much foliage on the bottom that it resembles a terrarium.”

Tea houses have traditionally been places where people met and socialized, serving as neighborhood gathering places the same way pubs do in Britain. Tea drinking customs in China include: 1) refill your friends cups; 2) turn the pot lid upside down to request more tea: and 3) say thank you to the waiter by tapping four times on the table. Tea ceremonies somewhat like those done in Japan are performed in the Anhui province of China.

Tea Agriculture See Agriculture, Economics

Websites: Stash Tea: www.stashtea.com ; Tea Council Tea Trail: www.teatrail.co.uk : Tea Council of the USA. www.tea.com

History of Tea

Originating from Southeast Asia and the Yunnan province of China, tea was mentioned in a Chinese dictionary around A.D. 350. Tea processing is believed to date to around A.D. 500.

Tea was brought to imperial China from Southeast Asia about A.D. 900. It became popular during Tang dynasty, when it was associated with Buddhism (monks reportedly used it to stay awake while meditating). During this period of time, tea was not prepared like it is today. The leaves were first steamed and compressed and then dried and pounded in a mortar. China still produces more varieties of tea than any other nation.

The consumption of tea spread from China to Japan and India between around A.D. 1000 or 1100, perhaps by Buddhist monks. It was originally brought over as a medicine not drink. It did not become popular in Japan with the aristocracy until the 17th century and did not really catch on with ordinary people until the 18th century.

In 1609 tea reached Europe via Amsterdam. The first tea to arrive in Britain came from China in 1652. The tea carried on ships in the Boston Tea Party came from China. The British established the tea industries in India and Sri Lanka.

Iced tea was invented in 1904 by an Englishman in St. Louis. He tried to introduce hot tea to the United States and had little success. Out of desperation he poured it over ice. The drink was an immediate success. The same year the same man came up with he novel of idea of selling tea in bags so that it could be dropped in the water.

Kinds of Tea

There are at least eight major types of tea. They include hundreds of well-known varieties of green tea, oolong, black and puer. There are different preparation methods. Green tea is prepared using fresh tea leaves that are first stir-fried; black tea is made from fermented fresh leaves; oolong tea is both fried and fermented in a process that makes the leaves green in the middle and red at the edges.

True teas (excluding so called "teas" from other plants) are divided into four categories according to methods of processing: 1) unfermented; 2) slightly fermented; 3) semi-fermented; and 4) fermented. The reference to fermentation is misleading because tea undergoes oxidation not fermentation.

There are thousands of different kinds of tea. Different soils, different climates, different altitude, different drying methods can all affect the flavor and look of a tea. Many companies blend teas and produce teas that favorable to people in certain regions.

Teas are also categorized by size, quality and the elevation they are grown. Tea particle sizes range from “dust,” to fannings and broken grades to “leaf” tea. Quality is described with words like flowery and pekoe (Orange Pekoe is a quality name that has nothing to do with the color of the tea or oranges).

Low-grown teas (those grown under 600 meters) are full bodied but lacking in flavor. High-grown teas (those grown above 1,200 600 meters) grow more slowly and are known their subtle flavor. Mid-grown teas are between the two. Most commercials teas are blends with some high-grown leaves for flavor and low-grown leaves for body.

There are at least 800 different types of Chinese tea. Chinese rank their teas and recognize their places of origin. They classify tea according to six colors: green tea, blue tea, red tea, white tea, yellow tea and dark green tea. The main varieties known in the West are green tea, black tea (the same as Chinese red tea) and oolong tea.

Bubble milk tea is a strong, milky iced tea with chewy tapioca balls. It is popular with the shopping mall crowd.

Green Tea and Black Tea

Green teas are the least processed of all teas. They are steamed, rolled and dried (in Japan) or pan fried (in China) soon after picking to kill the enzymes and prevent oxidation before drying. Green tea has a slightly bitter, grassy flavor. The fragrance at first is grassy but later becomes sweet. The taste has been described as "fresh, energetic and sweet."

Green teas are popular in Japan, China, Pakistan and Afghanistan. They have become more popular in the West since the discovery of possible health benefits associated with them. The most prized green tea — longjin — is produced mainly in the Hangzhou area of east China.

When making green tea, the water should ideally be cooled to 158̊F to 176̊F (boiling is 212̊F) and made in a broad-bottomed pot preferably made of stoneware that allows heat to escape and exposes the maximum amount of tea-leaf surface to the water. Longjin and other green teas are made in lidded white cup called a chung from which the tea is poured into smaller cups.

Black teas (red teas) are highly processed and oxidized. After they are picked the leaves are exposed to air, then crushed and stored in temperature- and moisture-controlled rooms, where they oxidize ("ferment"), which turns the leaves deep brown and intensifies their flavor. Grown primarily in India and Sri Lanka, these are the teas most familiar to Westerners and are the mostly widely consumed in Europe, North America, Russia and the Middle East Black teas are made in a slightly larger pot with water that is near boilng temperature.

Other Kinds of Teas

Dark green or black oolong teas are 30 to 70 percent oxidized. Most common in China, they are exposed to heat and light and crushed for less time than black tea. Their level of processing is about half way between green and black tea. They have a strong and sometime flowery fragrance and a fruity, mellow flavor. Common mainland oolong teas include Tikuanyin, Shuxian and Dahongpao. Taiwan oolong tends to be milder than mainland teas with an emphasis on fragrance over flavor.

Oolong teas are infused with nearly boiling water in very small round-bottomed pots that are almost filled to the top with leaves that expand in the water. A tea connoisseur told the New York Times, "Oolong is bitter and sweet, with good memories, sometimes quite uncomfortable. But only when you have seen the vicissitudes of life will you understand the meaning of it."

Relatively uncommon white teas are slightly oxidized and have a light, flowery fragrance. The leaves of white teas are light to medium brown and sometimes are covered by furry silvery hairs. Silver needles, white peony and shoumei are common white teas. White teas should be infused in water around 170̊F.

Scented teas, such as jasmine tea, and compressed teas in cake form are made both from oolong and red teas.

Herbal teas are made from a variety of plants. They are not true teas because they are not made with the tea plant. Red tea sometimes refers to herbal teas made from the South African rooibos shrub. It has a strong taste and smells earthy. It is high in antioxidants and is caffeine free.

Non-drink products made from tea include Green Tea Cooling Bubbles Foot Lotion and Green Tea Radiant Body Foam made by Elizabeth Arden. A French fragrance company has introduced a tea-scented perfume spray made with Chinese Lapsang Souchong, Indian Darjeeling and Sri Lankan Orange Pekoe. Super-model Claudia Schiffer and actresses Michelle Pfeifer and Isabelle Adjani are among those who are said to use it.

Asians Losing Interest in Tea

In 2007, Reuters reported: “From Beijing to Tokyo, Seoul, Hong Kong and Taipei, fast-paced modern life means that tea has little appeal for Asian youth who don't have the patience to wait the 10 minutes it takes to brew tea in the traditional way. "Consumption of traditional tea is declining because it's not being passed down," Taiwan tea expert Yang Hai-chuan told Reuters. "Basically there's no one promoting it." [Source: Reuters, 15 October 2007]

Yang teaches tea brewing classes to a handful of students. He sells sachets of mixed oolong and green tea leaves at teahouses across Taipei, marketing them as hip flavored beverages rather than the traditional teas that have been drunk for centuries. Determined to restore tea to its exalted status in Asia, tea lovers are trying to repackage tea as a funky new-age brew to a young generation more inclined to slurp down a can of artificially-flavored tea than to sip the real thing. They cater to younger people's fixations on their health and a thirst for novelty. In Japan, a new tea line is winning fans among young Japanese with its claims to reduce body fat, while a South Korean brand called "17 Tea" is popular for its claims to blend teas that cure a host of ills.

The elaborate tea making ceremonies of past centuries are largely defunct across North Asia, although traditional drinkers avoid Western tea bags and devoutly adhere to tea-making customs by pouring hot water from clay pots over tea leaves. Teahouses across the region, from airport waiting halls in China to parks and temples in Taiwan, continue the tradition but mostly to the older generation who are willing to pay up to $1 per gram for prime tea leaves.

Younger drinkers prefer canned tea, powdered tea, soft drinks and coffee. They increasingly refer to traditional tea as "old people's drink". Minoru Takano, director of the Japanese Association of Tea Production, admits that canned flavored teas have helped keep consumption levels up in Japan. "But we are concerned that tea culture will not be nurtured by these drinks," Takano said. "We are trying to promote making tea by the pot. There are some households that do not (even) have a pot. We are concerned that the tradition and culture may disappear."

Tea is so embedded in Taiwan culture that tea lovers can argue for hours about the merits of tea grades and water temperatures for preparation of the brew. But Taiwan youngsters won't have a bar of it. "Our children don't want to carry on the traditions, so in the future it will be forgotten," complained Wang Cheng-long, a life-long bulk leaf seller in Taiwan's historic tea-growing region of Pinglin. Many of those attending Yang's classes sign up mostly because of the coffee-making section in the course. "I don't have any time or relevant tea culture," says Becca Liu, a 25-year-old college graduate in Taipei. "I'm more curious to know how to make coffee."

Image Sources: Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, National Geographic, The New Yorker, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wall Street Journal, The Atlantic Monthly, The Economist, Global Viewpoint (Christian Science Monitor), Foreign Policy, Wikipedia, BBC, CNN, NBC News, Fox News and various books and other publications.

Last updated May 2021