DESPERATE JAPANESE MEASURES

Saratoga Kamikazee hit

In the battles at Okinawa and Iwo Jima, the Japanese fought to the death and used kamikaze attacks. Japanese youths were recruited at age 14 to fight. One Japanese soldiers recalled, "At the time, it was quite natural for us to volunteer for military service, to fight for the Emperor...This system of 'volunteering' was a virtual form of conscription. We were brainwashed into blind belief.”Japanese were taught that dying for their country was a great honor. "Bear in mind that duty is weightier than a mountain, while death is lighter than a feather," read a piece of propaganda attributed to the Japanese Emperor. Japanese soldiers who believed they were going to die washed themselves and splashed on perfume like their samurai ancestors.

In many cases Japanese soldiers preferred dying in hopeless circumstances to surrendering because of the power of shame. The military code issued to soldiers in 1941 forbade retreat or surrender. In 1945, as the United States was preparing to invade Japan, copies of the code were given to civilians. One Japanese scholar told the New York Times, “It had always been a virtue in Japan to sacrifice oneself for someone of higher status, and the government at the time exploited that sentiment.”

The Japanese were determined to die to the last man. At the assault of Tarawa (1943) only eight members of 5000 man Japanese garrison were found alive. There were no search and rescue missions for downed Japanese pilots. As a result hundreds of aviators were lost. The Japanese code of never surrender made them problematic prisoners of war. After captured Japanese soldiers tried to sabotage American submarines, U.S., ships refused to picked them except as for an occasional “intelligence sample.”

During the war, some Japanese have said, generals and admirals believed their own propaganda about Japan being a sacred country that could defeat its foes with spiritual purity alone, and thus allowed themselves to fall behind the United States in developing technology and building up their forces. “We were brainwashed during the war, “ one man told the New York Times.

The Japanese were not the only ones that performed suicide missions. An Australian who had won the Victorian Cross in World War I set off alone towards Japanese lines "with grenades in his hands and "no capitulation for me" on his lips. [Source: "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books]

See Suicide Bombers, Under Terrorism

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: OKINAWA, KAMIKAZES, HIROSHIMA AND THE END OF WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; IWO JIMA AND THE DRIVE TOWARD JAPAN factsanddetails.com; BATTLE OF OKINAWA factsanddetails.com; SUFFERING BY CIVILIANS DURING THE BATTLE OF OKINAWA factsanddetails.com;KAMIKAZE PILOTS factsanddetails.com; FIRE BOMBING ATTACKS ON JAPAN IN WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; DEVELOPMENT OF ATOMIC BOMBS USED ON JAPAN factsanddetails.com; DECISION TO USE TO ATOMIC BOMB ON JAPAN factsanddetails.com; ATOMIC BOMBING OF HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI factsanddetails.com; SURVIVORS AND EYEWITNESS REPORTS FROM HIROSHIMA AND NAGASAKI factsanddetails.com; HIROSHIMA, NAGASAKI AND SURVIVORS AFTER THE ATOMIC BOMBING factsanddetails.com; JAPAN SURRENDERS, THE USSR GRABS LAND AND JAPANESE SOLDIERS WHO DIDN'T GIVE UP factsanddetails.com; APOLOGIES, LACK OF APOLOGIES, JAPANESE TEXTBOOKS, COMPENSATION AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF THE ATOMIC BOMBING OF JAPAN AND OBAMA'S VISIT TO HIROSHIMA factsanddetails.com; LEGACY OF WORLD WAR II IN JAPAN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Memoirs of a Kamikaze: A World War II Pilot's Inspiring Story of Survival, Honor and Reconciliation” by Kazuo Odachi, Alexander Bennett - translator, et al. Amazon.com; “Blossoms in the Wind: Human Legacies of the Kamikaze” by M.G. Sheftall Amazon.com; “The Divine Wind: Japan's Kamikaze Force in World War II “ by R. Inoguichi, T. Nakajma and R. Pineau, 1959 Amazon.com; “Kamikaze: Japanese Special Attack Weapons 1944–45" by Steven J. Zaloga and Ian Palmer Amazon.com; “The Kamikaze Hunters: Fighting for the Pacific: 1945" by Will Iredale Amazon.com

Kamikaze

Kamikaze crashin near the USS Essex in 1945

Kamikaze were officially known as the Special Attack Forces, or Tokko in Japanese. According to to Associated Press: The U.S. Strategic Bombing Survey and data kept at the library at Yasukuni shrine in Tokyo estimate that about 2,500 of them died during the war. Some history books give higher numbers. About one in every five kamikaze planes managed to hit an enemy target.” [Source: Yuri Kageyama, Associated Press, June 17, 2015]

David Powers of the BBC wrote: “Even though nearly 5,000 of them blazed their way into the world’s collective memory in such spectacular fashion, it is sobering to realise that the number of British airmen who gave their lives in World War Two was ten times greater. Although presented in poetic, heroic terms of young men achieving the glory of the short-lived cherry blossom, falling while the flower was still perfect, the strategy behind the kamikaze was born purely out of desperation.” [Source: David Powers, BBC, February 17, 2011 ***]

The Japanese "tokko" campaign was incorporated as a military policy in July 1944 as a means to “destroy enemy aircraft carriers and transport ships at any cost. The strategy became a policy when the Tokko Department was established in September 1944. The first Kamikaze Special Attack For consisted of four units. In October, a 13-man attack force crash dove explosive-laden planes against enemy positions in the Philippines. About 700 pilots died in operation in the Philippines which continued until January 1945. The attacks had little impact on the fighting there.

Kamikaze attacks became a tactic in the sea battle for Okinawa. A handful of kamikaze pilots hit their targets, but the vast majority fell harmlessly into the sea. They caused relatively little damage; their most profound effect was psychological.

A total of 9,500 people died, including 3,535 Japanese, 34 warships were sunk and 185 were damaged in kamikaze attacks. In addition to this tens of thousands of Japanese soldiers and civilians died in the name of "gyokusai", which literally means “jewel smashing” but came to mean “dying an honorable death” either by uselessly throwing their lives away in futile attacks or committing suicide rather than being captured.

Kamikaze Attacks

Essex Hit

Kamikaze suicide attacks sunk 34 ships between October 1944 and the end of the war, and played a part in a the U.S. Navy's worst single day loss, at Okinawa. Named after a divine wind and "nature god" that saved Japan from a Mongol attack in the 13th century, kamikaze planes were usually ordinary service aircraft, loaded with bombs and extra fuel tanks that would explode on impact. They were the equivalent of human-powered cruise missiles, an idea not so different than the one behind the September 11, 2001 terrorist attack on the World Trade Center in New York.

Kamikaze pilots operated manned-flying bombs (“Oka”) and human-powered torpedoes (“Kaiten”) in addition to explosives-laden aircraft. The idea of the suicide attacks was a last ditch measure by the Japanese to inflict as much damage and carnage as possible to break the will of the Allied forces. The suicide bombers were part of a mission called Ten Go (Operation Heaven). Most kamikaze aircraft were aimed at ships, some where also aimed at American B-29 bombers.

Praising a kamikaze attack in June 1944 Tojo said: “The best thing about Japan is that all people will risk their lives and are not afraid to die...Making infinite use of this advantage, we can destroy the enemy with death squads, by which one airplane destroys one enemy vessel or one special submergible sinks one enemy vessel.”

Book: “Blossoms in the Wind” by Mordecai Sheftall (New American Library, 2005) Amazon.com; ; “The Divine Wind: Japan's Kamikaze Force in World War II “ by R. Inoguichi, T. Nakajma and R. Pineau, 1959 Amazon.com;

Film: “The Winds of God: Kamikaze” is a film about a couple of comedians who die in a bicycle accident and are reincarnated as kamikaze pilots.

History of Kamikaze Attacks

Okha Kamikaze glider Takijiro Onishi, the vice admiral who founded the kamikaze force, suggested that 20 million people might have to die to secure a Japanese victory. In additional to kamikaze aircraft, his staff also drew up plans for manned flying bombs, human torpedoes, and suicide boats.

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “In September 1944, the Japanese Army 4th Air Army and the Japanese Navy 1st Air Fleet conducted tests and concluded that tokko, short for tokubetsu kogeki or "special attack", during which the pilot carried the bomb all the way through the dive and releasing only a split second before the aircraft struck the enemy ship, was much more effective than the standard anti-ship bombing technique during which only one in four skills crews could score hits with bombs. The first authorized tokko attack took place on 13 September 1944 by Army planes based at Los Negros, Philippine Islands. On 17 Oct 1944, Vice Admiral Takijiro Onishi took command of the 1st Air Fleet, and soon organized a special unit within the 201st Air Group based in the Philippine Islands named Shimpu Tokubetsu Kogeki Tai, or "Divine Wind Special Attack Unit". The kanji characters used for shimpu could also be read as kamikaze especially in modern mortgage; despite Onishi’s usage of shimpu as the pronunciation, kamikaze became the common pronunciation in western literature.[Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, from “The Divine Wind” by Rikihei Inoguchi and Tadashi Nakajima,, “Seafire vs A6M Zero” by Donald Nijboer and “Kamikaze” by Steven Zaloga ]

Justin McCurry wrote in The Guardian, “By January 1945 more than 500 kamikaze planes had taken part in suicide missions, and many more followed as fears rose of an impending US-led invasion of the Japanese mainland. By the end of the war, more than 3,800 pilots had died. Although there are still disputes over their effectiveness, suicide missions sank or caused irreparable damage to dozens of US and allied ships. [Source: Justin McCurry, The Guardian, August 11, 2015]

Chen wrote: “Ultimately, aerial special attack did not improve the Japanese ability to defend the home islands significantly; the 296 tokko aircraft that had successfully hit an Allied shipping only managed to sink 45 ships, and most of them were targets of relatively less value such as destroyers and landing ships. The Japanese leadership continued to be blinded by optimism, however. A conference at the 6th Air Army headquarters in Jul 1945, for example, concluded that aerial special attacks could destroy as much as a third of the Allied invasion force sailing for Japan when the invasion came. The Japanese Navy was slightly more conservative in its faith in special attacks, but it was still plagued by over-confidence; the admirals believed that they would be able to organize a fleet of 2,400 tokko aircraft, and about 400 of them would be able to hit American ships of tactical value.”

Logistics of a Tokko (Kamikaze) Attack

Kamikaze pilots used a special plane called the Okha. Yuri Kageyama of Associated Press wrote: “Though the Zero was used in kamikaze missions, it was not designed for the task. The Ohka was. It was a glider packed with bombs and powered by tiny rockets, built to blow up. They were taken near the targets, hooked on to the bottom of planes, and then let go. Ohka means cherry blossom, and to this day kamikaze are associated with the briefly glorious trees. Americans called it the "Baka bomb." Baka is the Japanese word for idiot. Because their cruise range was so limited, they were easily shot down.” [Source: Yuri Kageyama, Associated Press, June 17, 2015 +++]

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “A tokko usually began with dispatch from a communications center, whose information came from forward reconnaissance aircraft. The special attack air group commander would then determine the attack force’s size base on weather, enemy strength, and the overall tactical objective. While the air group commander briefed the pilots, the ground crew fueled, armed, and warmed up the aircraft. The standard kamikaze aircraft were usually fighters or other similar light aircraft, while the standard armament were either four 60 kilogram or one 250 kilogram bombs. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, from “The Divine Wind” by Rikihei Inoguchi and Tadashi Nakajima,, “Seafire vs A6M Zero” by Donald Nijboer and “Kamikaze” by Steven Zaloga ]

“Depending on distance to the enemy and weather conditions, commanders determined the best launch time in order to reach the enemy at 1820 at the latest. The time was chosen in order to avoid reaching the enemy after sunset, after which time finding enemy vessels and selecting targets would become difficult. Some air group commanders preferred dawn attacks if the option was available to them. Dawn time attacks tend to encounter the least number of enemy interceptors en route.”

“A standard special attack group consisted of three tokko aircraft and two escort aircraft. The reason for such a formation was because the formation must be kept small enough to be launched in a short amount of time and could maneuver with maximum mobility. Three tokko aircraft was determined to be optimal as sometimes against a larger target such as a fleet carrier, multiple hits might be necessary to sink or disable the target.

“The two escorts were very important for that they were charged with warding off enemy interceptors. However, the escort fighters were not to initiate air duels before the target area was reached. If they were drawn into air combat before the target area was reached, they were not to depart from their general paths to seek vantage points. The reason for such an order was because the tokko aircraft must be guarded until the moment of attack. Any deviation in the flight paths on the part of the escort aircraft might create such a great distance between the escort aircraft and the kamikaze aircraft that catch up became impossible, leaving the kamikaze aircraft undefended when they reach the target area.

“During take off, pilots were instructed to not allow the cheering comrades to distract the take off procedures. After taking off, they kept the nose of their aircraft from rising too soon, maintaining an altitude of 50 meters while gaining air speed before climbing to cruising altitude. Finally, aircraft of a special attack force tend to take off successively with minimal time lapse between each launch; this prevented aircraft that took off earlier to have to circle the airfield waiting for the other aircraft. Aircraft typically took off in 100 meter intervals to prevent circling.”

Justin McCurry wrote in The Guardian, “By the latter stages of the war, Japan was relying on ageing planes that had been stripped and adapted for suicide missions. Many failed to start or encountered engine trouble en route to their targets. Most of those that got within striking distance of allied warships were shot down before they made impact. [Source: Justin McCurry, The Guardian, August 11, 2015]

Kamikaze Missions and Cherry-Blossom Plane

Some pilots only 17

Most of the kamikaze flights to Okinawa, Iwo Jima and other places near Japan took off from Chirancho in southern Kyushu, where there was also a training camp for kamikaze pilots. Most of the planes only carried enough fuel in their engine tanks for a one-way flight. The planes tended to be old and poor condition. One pilot wrote in his final letter, "I only hope I will be able to set off on my mission in a plane in good repair."

A Japanese pilot named Kaoru Hasegawa survived a kamikaze attack. After aborting two kamikaze missions he decided on his third try near Okinawa to "go to the goal this time." As he aimed his plane for an aircraft carrier he was shot by an American destroyer. He feel unconscious and was thrown from the plane when it hit the sea and was later rescued by the same ship that shot him down. He was taken to Guam for medical treatment. On the way there he tried to commit suicide because he felt dishonored because he failed in his mission

The thought that Japanese could kill themselves so easily gave American soldiers the willies. Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee wrote in The New Yorker: “I could not imagine myself in the heat of battle where I would perhaps instinctively take some sudden action that would almost surely result in death. I could not imagine waking up some morning at 5 a.m., going to the church to pray and knowing that in a few hours I would crash my plane into a ship on purpose.”

The "ohka" ("cherry blossom plane") was a glider that was released from the wing of a bomber near an enemy ship. Launched with three minutes of fuel, it contained a 2,600-pound bomb in its nose. The pilot who tried to slam the crafts into and enemy ship. The pilots of the ohka were called the Dive Thunderbolt Corps. Once deployed, the pilot had no means of escape.

Human-Powered Torpedoes

Kaiten

Forty-eight-foot-long "kai-ten" ("return to heaven") human-powered torpedoes could travel 48 miles at a speed of 10 knots. Packed with explosives, the nine-ton crafts were dropped from a mother ship and steered underwater towards an American ship by a pilot who used a periscope to see where he was going.

Kumiko Makihara wrote in the New York Times: “The human torpedoes were named kaiten, literally “turn heaven,” and shorthand for “shake up the heavens and change the course of the war,” reflecting Japan’s desperate desire to reverse the steady string of U.S. victories in the Pacific. They were the brainchild of the Imperial Navy officers Hiroshi Kuroki and Sekio Nishina who eyed the stockpiles of torpedoes sitting in sheds after Japan had shifted its focus of fighting from sea to air. The missiles were redesigned to have a tiny pilot’s chamber, an engine and a gyroscope so they could be steered into their targets. They began shipping out in 1944, the year before Japan’s defeat. [Source: Kumiko Makihara, New York Times, November 3, 2010]

“The volunteers “ if the men who signed up for the missions under immense pressure can be called that “ were mostly in their late teens and early 20s. Their writings describe a calm acceptance of their fate along with words of gratitude and affection to their families. Some are poetic, like the one of the 18-year-old who wrote, “I am the sea. I am normally calm and blue. The turbulent swirls are the angry me.”...They often addressed their final messages to their mothers. “That lunch box was really delicious. I should have asked you to make some more,” were the last words written by one 21-year old.

“To get a first-hand look at a kaiten, we visited Tokyo’s Yushukan military museum...The sleek missile, nearly 15 yards long, was striking in its length compared to the narrow one-yard diameter into which the soldier would squeeze. Painted in white on the hatch was a chrysanthemum floating on water, the family crest of a samurai loyal to the emperor. “The 1.5 tons of explosives in its bow instantly sank a ship,” reads the museum pamphlet.

“What it doesn’t say is that the more than 100 kaiten launches resulted in only two major sinkings of enemy vessels; the oiler U.S.S. Mississinewa and the destroyer escort U.S.S. Underhill. The torpedoes had limited maneuverability and often set out at night amid rough waters, making it difficult to reach their targets. U.S. ships frequently detected the submarines before the kaiten could even be deployed. And more than a dozen pilots died during training missions, having rammed their missiles aground.

Kamikaze Ship Attack

Training

C. Peter Chen wrote in World War II Database: “Tokko pilots were instructed to choose fleet carriers and escort carriers as their primary targets. As for the points of aim, special attack pilots were instructed to hit specific areas of each ship type. Against carriers, the most desirable point of aim was the central elevator where even a less than perfect attack might render the carrier’s function useless. Secondary points of aim against carriers were other elevators and the base of the bridge. Against other ship types, the base of the bridge or the area between the bridge and the center of the ship were both desirable. Like carriers, taking out the bridge of a ship meant disabling the ship’s combat-worthiness at least temporarily. Against ships of equal or smaller size of destroyers, a single successful hit between the bridge and the center of the target ship might cause it to break in half and sink. The points of aim, therefore, were determined based upon the desire to cause the greatest amount of damage with the least expenditure in aircraft and lives. Although pilots were made aware of the points of aim for smaller ships, many air group commanders discourage attacks on targets unworthy of a tokko attack; instead, some of the pilots were instructed to return to base if they could not locate an enemy carrier, battleship, or cruiser. [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, from “The Divine Wind” by Rikihei Inoguchi and Tadashi Nakajima,, “Seafire vs A6M Zero” by Donald Nijboer and “Kamikaze” by Steven Zaloga ]

“Escorting fighters sometimes returned to base reporting that some special attack aircraft crashed into the target vessel without causing an explosion. It was determined that some pilots, in the heat of the moment, would forget to release the bomb safety before hitting their targets. Standard operation procedure disallowed pilots from disengaging the bomb fuse safety before battle, because if the bombs were not expended before landing, they must be wastefully jettisoned into the ocean for a safe landing. Therefore, it became the responsibility of the escort pilots to fly close to the tokko aircraft before the dives to make a visual inspection. If they believe the bomb fuse safety were still engaged, they would remind the tokko pilots via hand signals or radio.

“During the diving attack, the tokko aircraft might approach the enemy vessel two different ways. The first method was the high attitude approach, where the aircraft approached the target at about 6,000 to 7,000 meters. The high altitude was vulnerable enemy radar or visual detection, but it took time for enemy fighters to reach the high altitude to intercept. If the enemy interceptor did reach the attack formation, it was hoped that the enemy pilots' ability to fight effectively might be reduced due to the thinner oxygen content of high altitude air. As the tokko aircraft approached, it began a shallow 20 degree dive until it reached about 1,000 to 2,000 meters in altitude, and then it dove sharply at 45 to 55 degrees, crashing toward the enemy vessel. Pilots were told to ensure the final dive angle would not be so steep that the aircraft might become out of control and miss the target.

“An extremely low altitude approach was also believed to be effective. With this method, the tokko aircraft hugged the ocean at a height of mere 10 to 15 meters while approaching the target area, avoiding radar and visual detection. However, as the aircraft neared the target, it must quickly climb to 400 to 500 meters in altitude, then begin a dive for the target vessel.”

Shooting Down Kamikaze

a defense against a kamikaze attack

British Royal Navy Fleet Air Arm pilot Lieutenant Commander Mike Crosley of 880 Naval Air Squadron aboard HMS Implacable commented after witnessing several tokko special attacks: “The kamikaze was a weird form of terrorism which seemed to us to deserve nothing but a painful death and eternal damnation. With their clever, decoy-led, low-level approach below the radar of the carrier air defence, it was worrying to think that 100 percent kills would be necessary before a sure defence could be provided. Each one of these part-trained, one-way aviators could park a 500lb bomb within a few feet of his aiming point if he was allowed to get within a few miles of the fleet. However, we felt that the Seafire, of all aircraft, would be the best possible defence in such circumstances, and we were not too frightened provided we could see the kamikazes coming.” [Source: C. Peter Chen, World War II Database, from “Seafire vs A6M Zero”]

Ray Anderson, a gunner on a U.S. navy ship, wrote: The fourth invasion was the small island of Ie Shima off the coast of Okinawa where Ernie Pyle, the famous war correspondent, was killed by a sniper bullet when he was on the front line looking out of a foxhole. Later when we were patrolling off the north shore of Okinawa a single Jap Kamikaze suicide plane spotted our ship and flew at our ship. Firing our guns we hit the plane so the pilot barely missed the mast of our ship and flew about 10 feet over my head where I was stationed with my gun crew in the bow of the ship, exploding in the sea about 50 yards from the ship and lifting the bow of our ship partially out of the water leaving me soaking wet from water that came over us. Petrified I thought that I would be killed and that my life was to end. Hundreds of beautiful tropical fish floated to the surface. [Source: Ray Anderson's Eyewitness Account to World War II, The American Legion, legion.org/yourwords ==]

“When we returned to the anchorage at Ie Shima our captain was summoned to the flagship where he was awarded a Bronze Star for heroism in battle. Our entire crew knew that he was a coward who left his station in the conning tower and fled to the rear of the tower for protection. Crew members who stayed at the battle stations firing guns, hitting the Jap plane with 20MM and 50-caliber machine guns which made the pilot miss the mast of our ship were the real heroes.” ==

Eyewitness Account of a Kamikaze Attack in November 1944

Describing a kamikaze attack on November 27, 1944 in the Leyte Gulf near the Philippines, James J. Fahey a seaman on the cruiser USS Montpelier, wrote: "At 10:50 A.M. this morning General Quarters sounded, all hands went to their battle stations. At the same time a battleship and a destroyer were alongside the tanker getting fuel. Out of the clouds I saw a big Jap bomber come crashing down into the water. It was not smoking and looked in good condition. It felt like I was in it as it hit the water not too far from the tanker, and the 2 ships that were refueling. One of our P-38 fighters hit it. He must have got the pilot. At first I thought it was one of our bombers that had engine trouble. [Source: Eyewitness to History.com; “Pacific War Diary 1942-1945 “ by James Fahey, 1963]

“It was not long after that when a force of about 30 Jap planes attacked us. Dive bombers and torpedo planes. Our two ships were busy getting away from the tanker because one bomb-hit on the tanker and it would be all over for the 3 ships. The 2 ships finally got away from the tanker and joined the circle. I think the destroyers were on the outside of the circle. It looked funny to see the tanker all by itself in the center of the ships as we circled it, with our guns blazing away as the planes tried to break through. It was quite a sight, better than the movies. I never saw it done before. It must be the first time it was ever done in any war.

“Jap planes were coming at us from all directions. Before the attack started we did not know that they were suicide planes, with no intention of returning to their base. They had one thing in mind and that was to crash into our ships, bombs and all. You have to blow them up, to damage them doesn't mean much. Right off the bat a Jap plane made a suicide dive at the cruiser St. Louis there was a big explosion and flames were seen shortly from the stern. Another one tried to do the same thing but he was shot down. A Jap plane came in on a battleship with its guns blazing away. Other Jap planes came in strafing one ship, dropping their bombs on another and crashing into another ship. The Jap planes were falling all around us, the air was full of Jap machine gun bullets. Jap planes and bombs were hitting all around us. Some of our ships were being hit by suicide planes, bombs and machine gun fire. It was a fight to the finish.

While all this was taking place our ship had its hands full with Jap planes. We knocked our share of planes down but we also got hit by 3 suicide planes, but lucky for us they dropped their bombs before they crashed into us. In the meantime exploding planes overhead were showering us with their parts. It looked like it was raining plane parts. They were falling all over the ship. Quite a few of the men were hit by big pieces of Jap planes. We were supposed to have air coverage but all we had was 4 P-38 fighters, and when we opened up on the Jap planes they got out of the range of our exploding shells. They must have had a ring side seat of the show. The men on my mount were also showered with parts of Jap planes. One suicide dive bomber was heading right for us while we were firing at other attacking planes and if the 40 mm. mount behind us on the port side did not blow the Jap wing off it would have killed all of us. When the wing was blown off it, the plane turned some and bounced off into the water and the bombs blew part of the plane onto our ship.

“A Jap dive bomber crashed into one of the 40 mm. mounts but lucky for them it dropped its bombs on another ship before crashing. Parts of the plane flew everywhere when it crashed into the mount. Part of the motor hit Tomlinson, he had chunks of it all over him, his stomach, back, legs etc.The rest of the crew were wounded, most of them were sprayed with gasoline from the plane. Tomlinson was thrown a great distance and at first they thought he was knocked over the side. They finally found him in a corner in bad shape.

“Planes were falling all around us, bombs were coming too close for comfort. The Jap planes were cutting up the water with machine gun fire. All the guns on the ships were blazing away, talk about action, never a dull moment. The fellows were passing ammunition like lightning as the guns were turning in all directions spitting out hot steel...The deck near my mount was covered with blood, guts, brains, tongues, scalps, hearts, arms etc. from the Jap pilots. The Jap bodies were blown into all sorts of pieces. I cannot think of everything that happened because too many things were happening at the same time."

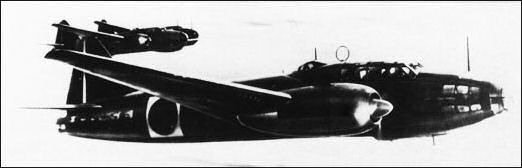

one kind of Kamikaze plane

Eyewitness Account of a Kamikaze Attack in May 1945

Describing a kamikaze attack on May 9, 1945, Michael Moynihan wrote:"Out of a clear evening sky Japanese Kamikazes swopped for the second time in five days on heavy hits of the British Pacific Fleet...The first two to penetrate the fighter and flak screen made for the same ship, an aircraft carrier. Both hit the flight deck and both by some lucky chance plunged from there into the sea, blazing wrecks." [Source: “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey, Avon Books, 1987]

"On the death dive of the third Kamikaze I had a breath-taking view from the Admiral's bridge. Its approach was signaled as usual by the gun flashes of battleship, carrier, cruiser, destroyer and a rash of some puff against the clear sky. The Zeke was flying low and we could see it now speeding on level course across the Fleet, ringed around, pursued by the bursting shells. It seemed to bear a charmed life, cutting unscathed through the murderous fail of flak. Less than a mile from us we saw it turn aft for another carrier. It was approaching its kill."

"The Jap climbed suddenly and dived. It was all a matter for seconds. He came up to the center of the flight deck, accurate as a homing plane, and abruptly all was lost in a confusion of smoke and flame. The whole superstructure of the ship disappeared behind billows of jet-black smoke and through flames as the tanks of aircraft ranged on the deck exploded."

"It seemed at the time that the ship was doomed, that nothing could service that inferno. But within half an hour the flames were extinguished...the damage seemed negligible for all that chaos of smoke and flame. When a few weeks ago this carrier was hit by a Kamikaze, planes were taking off again within seven minutes."

At 10:00am on May 10, 1945, a kamikaze pilot in a Japanese Zero crashed into the deck of the U.S. aircraft carrier “Bunker Hill” destroying 30 bomb-laden American planes. Thirty seconds later another suicide bomber with 550 pounds of explosives tore into the vessels amidships, blasting a 49-foot hole and setting off a fire that blazed for six hours and took the lives of 353 of the ships 3,000-member crew.

Ohka Cherry Blossom kamikaze glider

Fear and Cutting Off the Ears of a Kamikaze

Ray Anderson wrote: “Several days after that event as I was walking through the crew mess hall I spotted a glass jar on the bookshelf. They explained that the dead pilot had floated to the surface and they fished him out of the sea, cut off his ears, threw his body back into the sea and then put his ears in a bottle with medical alcohol. That was their victory trophy. Incensed, I threw the contents of the bottle into the sea, assembled the crew at General Quarters and delivered one of my more passionate lectures condemning their barbaric act. [Source:Ray Anderson's Eyewitness Account to World War II, The American Legion, legion.org/yourwords ==]

“One night we were ordered to anchor close to a cargo ship that was loaded with ammunition. Several Jap Kamikaze planes came into the harbor and we knew that if they hit the cargo ship the resulting massive explosion would have blown our ship out of the water. I was so frightened that I collapsed and fell down on the deck. The strain became almost unbearable. Our radioman, a young man with a wife and two small children back in the states, couldn't stand the tension and became hysterical. We had to strap him on a bunk and assign several crew members to hold him down trying to calm him until we were able to transfer him to a hospital ship the next morning.” ==

At Okinawa, “I especially remember the "turkey shoot" one afternoon when 69 Jap Kamikazes flew into the harbor where or fleet was anchored. We exhausted our ammunition firing our guns at them. Their targets were larger ships such as battleships, aircraft carriers, cruisers and destroyers and they succeeded in inflicting major damage to our fleet. A shell probably fired by one of our destroyers exploded on our gun deck with shrapnel hitting our ready boxes, ventilator and wounding five crew members who were temporarily evacuated to a hospital ship for treatment.

Kaiten schema

Legacy of Kamikazes and Human Torpedoes

Kumiko Makihara wrote in the New York Times: I was blown away when my son told me he wanted to do his sixth grade research project on Japan’s human torpedoes...Since then I’ve been watching to see if an 11-year-old boy growing up in an officially pacifist country “ Japan’s Constitution renounces war and the country only has forces for defense “ can fathom a time when thousands of frenzied young men signed up to ride torpedoes, or planes in the case of the better known kamikaze pilots, to meet certain death in the name of the emperor and their country. [Source: Kumiko Makihara, New York Times, November 3, 2010]

Nationalism is a remote concept for Japanese children today. The flag and national anthem remain controversial symbols of war-time militarism in some sectors. The government encourages public schools to raise the flag and sing the anthem, but my son’s private school never mandates those acts. My son cannot recite the lyrics to the anthem even though it happens to be one of the shortest in the world, with only 11 measures.

An avid reader, my son immersed himself in books filled with letters, wills and diaries of the soldiers. My mother became worried that her grandson was getting brainwashed after she heard him say in an admiring tone, “They did it for the emperor.” She pointed out that the officers were men not that much older than him...At the Kaiten Memorial Museum on a small island off the coast of Western Japan’s Yamaguchi Prefecture, stone tablets bearing the names of the dead dot what was once the parade ground of the country’s largest kaiten base. My son skipped around the tiny monuments, calling out the names he recognized.

Legacy of Kamikazes and Human Torpedoes

Kumiko Makihara wrote in the New York Times: I was blown away when my son told me he wanted to do his sixth grade research project on Japan’s human torpedoes...Since then I’ve been watching to see if an 11-year-old boy growing up in an officially pacifist country “ Japan’s Constitution renounces war and the country only has forces for defense “ can fathom a time when thousands of frenzied young men signed up to ride torpedoes, or planes in the case of the better known kamikaze pilots, to meet certain death in the name of the emperor and their country. [Source: Kumiko Makihara, New York Times, November 3, 2010]

Nationalism is a remote concept for Japanese children today. The flag and national anthem remain controversial symbols of war-time militarism in some sectors. The government encourages public schools to raise the flag and sing the anthem, but my son’s private school never mandates those acts. My son cannot recite the lyrics to the anthem even though it happens to be one of the shortest in the world, with only 11 measures.

An avid reader, my son immersed himself in books filled with letters, wills and diaries of the soldiers. My mother became worried that her grandson was getting brainwashed after she heard him say in an admiring tone, “They did it for the emperor.” She pointed out that the officers were men not that much older than him...At the Kaiten Memorial Museum on a small island off the coast of Western Japan’s Yamaguchi Prefecture, stone tablets bearing the names of the dead dot what was once the parade ground of the country’s largest kaiten base. My son skipped around the tiny monuments, calling out the names he recognized.

“What’s he famous for?” I asked him about one of them. Taro Tsukamoto made an audio recording of his will, my son told me. Sure enough, at the Yushukan museum one can hear through the static, the voice of the 21-year-old reminiscing about gathering silver grass for moon-viewing parties and having snowball fights. “I wish I could live happily like that forever,” he says. “But I must not forget that I am foremost a Japanese. ... May my country flourish forever. Goodbye everyone.” Six months after he started research, I asked my son what he thought about the kaiten. “I can’t say,” he said, causing me to momentarily worry about the outcome of his report. But then he explained, “You can’t describe in words how sad it is.”

Image Sources: National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, “History of Warfare “ by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, “The Good War An Oral History of World War II” by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016