ALLIED PRISONERS OF WAR HELD BY JAPAN

The Japanese captured approximately 350,000 prisoners of war, more than half of whom were natives. For propaganda purposes most of the native prisoners were released while 140,000 white prisoners — mainly from Britain, Australia, the United States, New Zealand, the Netherlands and Canada — were kept. The death rate among Japanese POWs was 27 percent, compared to 4 percent for Allied prisoners held in German and Italian camps.Nearly 50,000 U.S. soldiers and civilians became prisoners of wars. Nearly half were forced to work as slave laborers. About 40 percent of American POWs died in Japanese captivity (by contrast only 1 percent died in Nazi camps). Many were killed in fire bomb attacks and atomic bomb blasts or died while being transported to Japan. By one estimate one third of the Allied prisoners who died in captivity died from "friendly fire," including the Atomic bomb.

Allied prisoners endured the Bataan Death March, prison camps throughout Southeast Asia and the Pacific, slave-labor construction of the Siam-Burma railroad, transport by "hellships" back to Japan, and enslavement in Japan. One reason why POWs were treated so poorly was because of the Japanese belief that surrender was dishonorable.

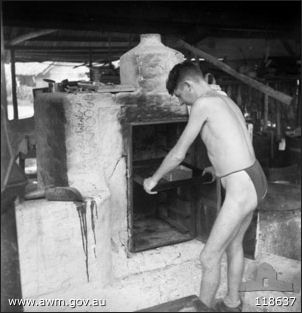

Allied prisoners tried to stave off disease by constructing spotless kitchens and latrines; using bamboo pipes, which brought in cholera-free water from spings miles away: and burning the dead in funeral pyres so they wouldn’t contaminate the living. The prisoners carried out these tasks after torturous, 16-hours work stints, during time they could have spent sleeping. In many cases their efforts proved futile. Scores were dispatched by malaria, dysentery, cholera or starvation anyway.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PEARL HARBOR, JAPANESE VICTORIES AND OCCUPATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF WORLD WAR II IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC factsanddetails.com; PEARL HARBOR AND EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS OF THE ATTACK factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com; JAPAN DEFEATS THE BRITISH AND TAKES MALAYA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com; JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR AND THE BATAAN DEATH MARCH factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com INTERNED JAPANESE AMERICANS DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; FORCED LABORERS IN ASIA IN WORLD WAR II AND THE DEATH RAILWAY IN THAILAND AND BURMA factsanddetails.com; COMFORT WOMEN factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Hidden Horrors” by Yuki Tanaka. Amazon.com; “Prisoners of the Japanese “by Gavan Daws. Amazon.com; ”The Bridge Over the River Kwai” by Pierre Boulle, a classic novel that inspired the film Amazon.com; “Uncommon Brutality: 101 Incidents of Japanese War Crimes during World War II” (Volume 1) by Donald Yates Amazon.com; “Uncommon Brutality: 101 Incidents of Japanese War Crimes during World War II” (Volume 2) by Donald Yates Amazon.com; “World War II and Southeast Asia” by Gregg Huff Amazon.com; “Japan's Infamous Unit 731: Firsthand Accounts of Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program” (Tuttle Classics) by Hal Gold and Yuma Totani Amazon.com; “Unit 731 Testimony: Japan's Wartime Human Experimentation Program” by Hal Gold Amazon.com;

Brutal Treatment of Allied Prisoners of War

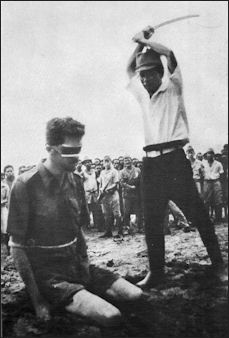

POWs on carts

The Japanese were very brutal to their prisoners of war. Prisoners of war endured gruesome tortures with rats and ate grasshoppers for nourishment. Some were used for medical experiments and target practice. About 50,000 Allied prisoners of war died, many from brutal treatment.Americans were shocked by a photograph run in American newspapers showing a Japanese soldiers raising his sword to behead an Allied prisoner of war, bound and tied and bent over on his knees. Captured airmen shot down over Japan were "beaten to death, beheaded, buried alive, cut into pieces for medical experiments and in a few cases eaten by vengeful Japanese." Some POWs were publically displayed naked in 4-x-5-foot cages. Captured B-29 bombardier Raymond "Hap" Halloran shrunk from 215 to 122 pounds and was displayed naked in a cage at the Tokyo Zoo, where people cursed and threw things at him.

In book entitled “Prisoners of the Japanese”, Gavan Davis wrote, "The idea that a soldier would surrender rather than die, or stay alive in a prison camp rather than kill himself, was just alien to the Japanese."

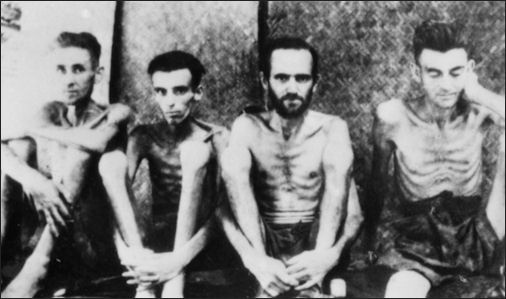

Allied prisoners liberated from Japanese POW camps looked like those liberated from Auschwitz. At the end of the wars Japanese soldiers at prisoner of war camps were told to behead, stab or shoot the 100,000 or so remaining Allied prisoners the moment an invasion began.

Accounts from Prisoners of War

Australian prisoner of war Russell Braddon wrote: “Outside Kanu in a small stream that trickled down from the mountain above, lay a naked man. When asked why he lay there, he pointed to his legs. Tiny fish nibbled at the rotten flesh around the edges of his ulcers. Then he pointed inside the camp. Other ulcer sufferers, reluctant to submit to this nibbling process, wore the only dressing available — a strip of canvas from a tent soaked in Eusol. Their ulcers ran the whole length of their shin bones in channels of putrescence. Looking back on the man in the stream it was impossible to decide, even though he was insane, which treatment was the best." [Source: “The Naked Island” by Michael Joseph]Describing a man who took care of the funeral pyres, Braddon wrote: "He stripped the dead of their gold caps; he stole fearlessly from the guards who dared not touch him less he contaminate them; he cooked what he stole...on the fire where he burnt the bodies.” Once,"as he leaned forward to pick up a faggot, the body he had just tossed into the flame, its sinews contracted, suddenly sat upright and grunted, and its hand thrust out a flaming hand on to the cigarettes in the man's mouth. With a scream of terror the man who had burnt hundreds of bodies with callous indifference fell backwards, his hands over his eyes. When the workers reached him he was jabbering and mad.”

Execution of an Allied Intelligence Officer

Describing the execution of an Allied intelligence officer in New Guinea on March 29, 1943, an anonymous Japanese soldier wrote: " Major Komai stands up and says to the prisoner, 'We are going to kill you.' When he tells the prisoner that in accordance with Japanese “Bushido” he would be killed with a Japanese sword and would have two or three minutes grace, he listens with bowed head." [Source: “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey, Avon Books, 1987]

"Now the time has come and the prisoner is made to kneel on the bank of a bomb crater, filled with water. He is apparently resigned. The precaution is taken of surrounding him with guards with fixed bayonets, but he remains calm. He even stretches his neck out. He is a very brave man indeed...The Major had drawn his favorite sword...He taps the prisoners neck slightly with the back of the blade, then raises above his head with both arms and brings it down with a powerful sweep."

"A hissing sound — it must be the sound of spurting blood, spurting from the arteries: the body falls forward. It is amazing — he has killed him with one stroke. The onlookers crowd forward. The head, detached from the trunk, rolls forward in front of it. The dark blood gushes. It is all over. The head is dead white, like a doll...A seaman...turns the headless body over on its back and cuts the abdomen open with one clean stroke. They are thick skinned, these “keto” [hairy foreigner] even the skin of their bellies is thick."

Sandakan Death March

During the little publicized Sandakan Death, which began in March, 1945 more than 2,700 British and Australian soldiers were forced to march through the steamy jungles of Borneo only to be shot when they reached their destination. Six men escaped — they survived by eating birds and monkeys as well as bugs and crawfish — but only one man survived the war.

The prisoners were brought to Sandakan in 1942 to build an airstrip. As the war went against the Japanese, food and medical supplies ran short and disease spread. Towards the end of the war, the Japanese feared an invasion and decided to move the soldiers inland. Those that couldn't keep up were executed on the spot. When rice supplies ran low prisoners were killed so there was more food for the Japanese soldiers. According to one war crime testimony, a Japanese sergeant told one group of condemned prisoners, "There's no rice, so I'm killing the lot of you today. Is there anything you want to say?"

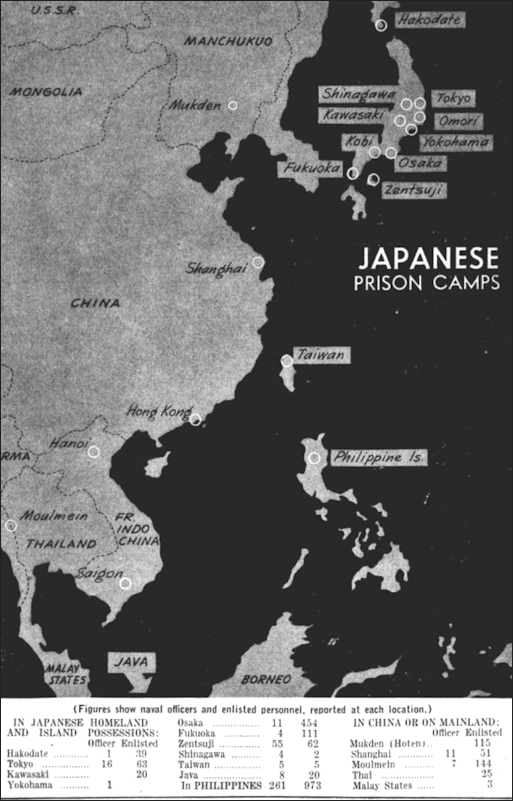

American Prisoners of War in Japan

About 36,000 Allied prisoners of war were held in Japan during the war. Most were forced to work, under extremely harsh conditions, in coal mines, shipyards and munitions factories. The mortality rate was as high as 27 percent, according to the POW Research Network Japan, and many of those who survived went home emaciated. [Source: Anna Fifield, Washington Post , October 16, 2014]

According to James D. Morrow, "Death rates of POWs held is one measure of adherence to the standards of the treaties because substandard treatment leads to death of prisoners."

Western Allied POWs held by Japan: 27 percent (Figures for Japan may be misleading though, as sources indicate that either 10,800 or 19,000 of 35,756 fatalities among Allied POW's were from "friendly fire" at sea when their transport ships were sunk. Nonetheless, the Geneva convention required the labelling of such craft as POW ships, which the Japanese neglected to do. [Source: Wikipedia]

Japanese POW camps in World War II

Experiences of American POWs in Japan

Bill Sanchez was an American prisoner of war at camps in Heiwa Jima and Tokyo in Japan in World War II. He spent 42 months doing back-breaking work there after being brought to Japan on a “hell ship” in 1942 after U.S. forces surrendered in the Philippines, where he was stationed. In Tokyo, he worked as a stevedore, hauling coal and lumber from barges on the canal at a railway yard.“I went through all that suffering, and the Japanese went through all those bombings,” he told the Washington Post. [Source: Anna Fifield, Washington Post , October 16, 2014 -]

Jack Schwartz was a Navy civil engineer captured on Guam on the third day of the war. Oral Nichols was was a civilian helping to oversee the construction of an airstrip on Wake Island when it fell easily to the Japanese. He was imprisoned for virtually the entire war. Schwartz was sent to Kawasaki, south of Tokyo, and spent more than half of his 1,367 days as a POW at a camp there. As an officer, he had been put in charge of the camp. He said he suffered his share of beatings but told the Washington Post, “I consider myself the luckiest POW. I didn’t have to do hard labor because I was an officer, and I didn’t get that sick, and I was never that terribly mistreated.” -

Schwartz kept a diary while in the camp. One entry reads, “September 2. Arrived at Yokohama at nine and took 10 minute ride to Kawasaki. Trucked to camp. What a place. High stockade. 2nd floor windows barred. Other prisoners were already present. We were forced by a firing squad to take an oath not to escape etc.” -

Dutch Japanese Prisoner of War

Jan Bras was the son of a Dutch planter in Indonesia. He was the youngest child of eight children. In World War II he became a Japanese prisoner of war (POW). Elizabeth Day wrote in The Guardian: “From the formative ages of 18 to 21, Jan Bras was a Japanese prisoner of war. When the Japanese invaded the Dutch East Indies during the second world war, he was transported by “hell ship” and cattle wagon to work on the construction of the Burma railway. Later, he was interned in a camp and sent to work in the perilous coal mines at Fukuoka. After liberation in 1945, he was one of the first to walk through a decimated Nagasaki after the detonation of the atomic bomb. [Source: Elizabeth Day, The Guardian, July 26, 2015 ]

“He witnessed unimaginable terror, brutality and death. Throughout it all, Jan Bras survived. For years Bras did not talk about what had happened to him....But then, about 10 years ago, the memories started floating to the surface like driftwood. Scraps at first, then entire stories: the occasion he watched his best friend die; the day his older brother was threatened with execution in the camp, the time he and his fellow prisoners were forced to dig their own graves.

“Bras and his older brother joined the Dutch army three months before war broke out. After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Japan was able to pursue its military objectives against the allies, including the conquest of the Dutch East Indies. By early 1942, the entire Bras family had been taken prisoner. Of the many acts Bras is unable to forgive, the death of his father is the most painful. His father was tortured by Japanese guards: they fed a tube into his mouth and poured water through it until his stomach burst and he died of his injuries. Remarkably, the rest of the family – Bras’s four sisters and his brother – all survived the war. After it ended, Bras and his mother emigrated to Amsterdam, where he pursued medical studies. For a while he and his brother worked in Kingston, Jamaica, where Bras later met his wife, a Scottish doctor. In 1958 they settled in Wrexham in Wales, where Bras worked as a GP for nearly 30 years.

POWs in Burma-Thailand

Dutch Japanese POW Works on Death Railway in Thailand

Elizabeth Day wrote in The Guardian: “Bras and his older brother Gerrit were among thousands transported to Thailand on the notorious hell ships. Their ship was subjected to heavy bombardment and Bras remembers hearing the sound of the bombs dropping in the ocean around them as they made the perilous crossing.“Yes, we were scared,” he says now. “We thought we would drown like rats. We were deep in the hold, covered from the top by a sheet. Two people suffocated. It was a terrible situation.”From Thailand they were taken by cattle wagon to the site of the Burma railway. There, the two brothers joined forced labourers digging 5m trenches and setting down sleepers in desperate conditions. Construction of the 415km railway cost the lives of around 13,000 PoWs and 100,000 native labourers. One man died for every sleeper laid. [Source: Elizabeth Day, The Guardian, July 26, 2015 ]

“Bras says the danger came not from the beatings the Japanese guards meted out at random intervals (“They passed,” he says phlegmatically, “and they didn’t want to kill us because they needed us to work”), but from the threat of cholera and malnutrition. He recalls being “always hungry”, but thinks he survived because, unlike some of his British counterparts, he was acclimatised to the tropics.

“His brother, who was a trainee pathologist, knew it was imperative to boil water before drinking it. Those who didn’t “died like flies”. There was a seasonal elevation of the Kwai owing to high rainfall. Once, after the waters receded, Bras remembers seeing the corpses of people who had died from cholera littering the branches of the trees bordering the river. Bras spent two years on the railway. He and his brother would supplement their meagre daily rice rations with strips of young bamboo and the odd squirrel thrown in for protein.

“Has he seen the film The Bridge on the River Kwai? “Yes!” he says, his voice whooping with laughter. “I think it’s a very beautiful film, but completely beyond the truth.” They did not spend their time singing and dancing and putting on shows, he says. “It [the film] was so ridiculous for a person who experienced the reality. It… it was a joke.”

Dutch POW Doing Hard Labor in Japan

Elizabeth Day wrote in The Guardian: “Extraordinary as it may seem, Bras regards his time on the railway as comparatively tolerable considering what came next. He was taken to Japan, where he was interned in a prisoner of war camp in Fukuoka, on the southern island of Kyushu, and forced to work in the nearby coal mines. It was “very dangerous” work, conducted underground amid the dark and soot, with the constant threat of death. Bras missed being able to see the sky. At night, he was plagued by fleas and could barely sleep. One in three prisoners died in the mines. Bras’s best friend was one; he was made to drill down below a section of lake and was killed when the roof collapsed on top of him.“I had to wash his clothes,” Bras says. “I found brain tissue on them.” [Source: Elizabeth Day, The Guardian, July 26, 2015 ]

“The way he coped was “by trying to do as little as possible. We were out there to sabotage the place… You try to forget a lot. It was so terrible in the mines. It was hard work, and the Japanese always had a stick to beat you with.” After a while Bras became so ill with jaundice he was transferred to the camp sick bay, where his brother was working. He became a medical orderly as a means of escaping the mines. But camp life was relentlessly harsh and unforgiving. “If the Japanese were annoyed for some reason or other, we would be lined up one in front of the other and we had to punch each other and if we didn’t do it hard enough, the guards would beat us up with a stick and tell us to beat each other harder.” His eyes become veiled and tired. “You were beaten by your own kind.”

“And yet, he says, the unexpected conflagrations of violence from their Japanese captors were much worse. At least, with an organised beating, you knew “it would end… The unknown things were more frightening.” The prisoners were expected to bow to the ground and say “Good day” in Japanese every time they passed a guard. On one occasion, when Bras forgot to do so in his haste to carry two buckets of water to the sanatorium, he was savagely beaten.

“This guard beat me up until I was really black and blue,” Bras says. He is matter-of-fact when he talks about this, and refuses to dwell on either the pain or the injustice. Almost immediately, he manages to seize on the slenderest filament of a positive: “One of the good things he did was that he never kicked my testicles, which he could easily have done. It sounds silly to you, but I could see there was some sort of honour in him. He beat me up terribly, but he didn’t kick my testicles or my stomach. In those days I believed in God. I was really very religious and I think it might have helped me...It never occurred to me to question God at that time...Since then I have completely changed my mind.”

The camp was liberated in September 1945. Bras vividly recollects the American planes flying overhead, dropping shoes, biscuits and cheese on to the ground below. Waiting in a truck by the train station, Bras remembers a Japanese camp guard meeting his eye. This particular guard had never beaten him and had always been polite. The guard saluted Bras. Bras looked away, refusing to return the salute. “Until now, I regret it,” Bras says. “I often think of it.”

Gruesome Experiments on American Airman at Kyushu University

Allied POW

Eight American airmen recovered from a B-29 shot down near the end of the war were taken to the anatomy department at Kyushu University where they had their organs ripped out of their body while they were still alive. One prisoner was shot in the stomach to give surgeons practice removing bullets. Another had parts of his body amputated while he was till alive. Another had one of his lungs removed and then was stitched back up to see what would happen. “The Sea and Poison” (1957) by Shusaku Endo is a novel based on the real-life vivisections of American prisoner of war at Kyushu University.

In early May 1945, a US B-29 Superfortress crashed in northern Kyushu after being rammed by a Japanese fighter plane. The US plane, part of the 29th Bomb Group, 6th Bomb Squadron, had been returning to its base in Guam from a bombing mission against a Japanese airfield. Justin McCurry wrote in The Guardian, “One of the estimated 12 crew died when the cords of his parachute were sliced by another Japanese plane. On landing, another opened fire on villagers before turning his pistol on himself. Local people, incensed by the destruction the B-29s were visiting on Japanese cities, reportedly killed another two airmen on the ground.“The B-29s crews were hated in those days,” Toshio Tono, now the 89-year-old director of a maternity clinic in Fukuoka, told the Guardian. [Source: Justin McCurry, The Guardian, August 13, 2015 ]

“The remaining airmen were rounded up by police and placed in military custody in the nearby city of Fukuoka. The squadron’s commander, Marvin Watkins, was sent to Tokyo for questioning. There, Watkins endured beatings at the hands of his interrogators, and is thought to have died in his native Virgnia in the late 1980s.The prisoners were led to believe they were going to receive treatment for their injuries. But over the following three weeks, they were to be subjected to a depraved form of pathology at the medical school – procedures to which Tono is the only surviving witness.

“One day two blindfolded prisoners were brought to the school in a truck and taken to the pathology lab,” Tono said. “Two soldiers stood guard outside the room. I did wonder if something unpleasant was going to happen to them, but I had no idea it was going to be that awful.” Inside, university doctors, at the urging of local military authorities, began the first of a series of experiments that none of the eight victims would survive. According to testimony that was later used against the doctors and military personnel at the Allied War Crimes Tribunals, they injected one anaesthetised prisoner with seawater to see if it worked as a substitute for sterile saline solution.

“Other airmen had parts of their organs removed, with one deprived of an entire lung to gauge the effects of surgery on the respiratory system. In another experiment, doctors drilled through the skull of a live prisoner, apparently to determine if epilepsy could be treated by the removal of part of the brain. The tribunals also heard claims from US lawyers that the liver of one victim had been removed, cooked and served to officers, although all charges of cannibalism were later dropped owing to a lack of evidence.

“Medical staff preserved the POWs’ corpses in formaldehyde for future use by students, but at the end of the war the remains were quickly cremated, as doctors attempted to hide evidence of their crimes. When later questioned by US authorities, they claimed the airmen had been transferred to camps in Hiroshima and had died in the atomic bombing on 6 August. On the afternoon of 15 August, hours after the emperor had announced Japan’s surrender, more than a dozen other American POWs held in Fukuoka camps were taken to a mountainside execution site and beheaded.”

Japanese Doctor Who Witnessed Human Experiments on U.S. POWS

Japanese propaganda poster

In 1945, Toshio Tono was a first-year student at Kyushu Imperial University’s medical school. Justin McCurry wrote in The Guardian, “For a while after the end of the second world war, Toshio Tono could not bear to be in the company of doctors. And the thought of putting on a white coat filled him with dread. Amid widespread criticism, including in the US, that under Abe Japan is attempting to expunge the worst excesses of its past brutality from the collective memory, Tono believes his “final job” is to shed light on one of the darkest chapters in his country’s modern history. [Source: Justin McCurry, The Guardian, August 13, 2015 ]

“As an inexperienced medical student, Tono’s job was to wash the blood from the operating theatre floor and prepare seawater drips. “The experiments had absolutely no medical merit,” he said. “They were being used to inflict as cruel a death as possible on the prisoners. “I was in a state of panic, but I couldn’t say anything to the other doctors. We kept being reminded of the misery US bombing raids had caused in Japan. But looking back it was a terrible thing to have happened.”

“Of the 30 Kyushu University doctors and military staff who stood trial in 1948, 23 were convicted of vivisection and the wrongful removal of body parts. Five were sentenced to death and another four to life imprisonment. But they were never punished. They were the beneficiaries of the slow pace of justice as US-led occupation authorities attempted to deal with large numbers of military leaders and civilian collaborators suspected of war crimes. One of the most senior doctors, Fukujiro Ishiyama, killed himself before his trial.By the early 1950s the Korean peninsula was in the midst of a bloody civil war, while Japan had been officially recognised as a US ally under the terms of the San Francisco peace treaty.With a politically stable Japan regarded as key to preventing the spread of communism in the region, President Truman issued an executive order that led to freedom for imprisoned war criminals, including those awaiting execution.

“By the end of 1958, all Japanese war criminals had been released and began reinventing themselves, some as mainstream politicians, under their new, US-authored constitution. “The way Japan was during the war, it was impossible to refuse orders from the military,” Tono said. “Dr Ishiyama and the other doctors committed crimes, but in a way they were also victims of the war. But I hated doctors for a while. I couldn’t get to sleep without pills.”

“After the war, Tono spent years examining documents and revisiting relevant locations in an attempt to establish what had happened. Ignoring pleas from his former superiors not to disclose the truth about the POWs’ treatment, Tono revealed all in Disgrace, his meticulously researched account of the crimes. Like the leaders of Unit 731, the doctors who conducted live vivisection re-entered postwar society as respectable members of the medical community. Most never spoke of their wartime experiences.”

In 2015, “the university, which has long since dropped its imperial title, made the surprising decision to acknowledge the darkest chapter in its history with the inclusion of vivisection exhibits at its new museum. Tono, too, is currently displaying photographs and documents at his clinic. Seven decades on, a simple stone monument erected by a local farmer marks the spot where the B-29 came down, and where the airmen’s terrifying ordeal began. “The job of a doctor is to help people, but here were doctors doing exactly the opposite,” Tono said. “It’s difficult to accept, but this really happened. I decided to tell the truth because I don’t want anything like this to ever happen again.”“

Japanese Propaganda

The Japanese press ran fanciful tales of U.S. planes being downed by rice balls.

Tokyo Rose — who infamously dished out Japanese propaganda in English aimed at American GIs fighting against the Japanese — was Iva Toguri D’Aquino, an English-speaking woman working for the Japanese propaganda outlet Radio Japan . D’Aquino was a U.S. citizen. In 1941, she went to Japan to care for a sick aunt and got stuck there during the Pearl Harbor bombing. Suddenly an enemy, she was forced to work for Radio Japan. Although she made an effort to get food for Allied POWs and remained loyal in her heart to Americans — referring to her audience in her radio shows as “our friends-I mean out enemies” — she was convicted of treason in 1949 and jailed for six years. She was given a pardon by U.S. President Gerald Ford in 1977. She died in Chicago at the age of 90 in 2007.

See Kamikaze Pilots

Japanese Prisoners of War Held by the Allies

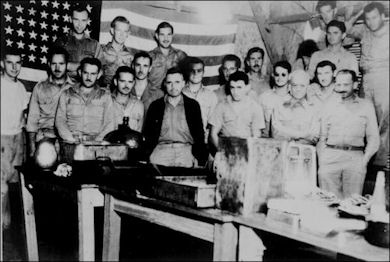

Americans with Japanese POW

There were relatively few Japanese prisoners of war: only around 20,000 were captured between 1939 and 1940. This was because it was considered shameful and sacrilegious to surrender rather than die. Those that did become prisoner were found unconscious or wandering in the jungle or were lured out of the caves and bunkers by skilled negotiators. Some had simply had enough.

The historian Peter Straus said, "It had been thoroughly planted in the minds of all Japanese that to become a prisoner of war was by far the worst thing that they could do, that they would cast dishonor not only on themselves but also on their families and nation." In Japan the media made "a big deal of those who... had gone back to the Japanese lines and then killed themselves, or those who had heroically given their lives in suicide missions.

Japanese POWs turned out to be an extraordinary intelligence coup for the Allies. Many felt they had already dishonor themselves by surrendering and had no hope of returning home so they had little to loose by giving up important information. The Japanese POWs were also generally astounded at how well they were treated after they were captured.

Atrocities by U.S. Soldiers in World War II: Not Taking Japanese Prisoners

American soldiers in the Pacific often deliberately killed Japanese soldiers who had surrendered. According to Richard Aldrich, who has published a study of the diaries kept by United States and Australian soldiers, they sometimes massacred prisoners of war. Dower states that in "many instances ... Japanese who did become prisoners were killed on the spot or en route to prison compounds." According to Aldrich it was common practice for U.S. troops not to take prisoners.This analysis is supported by British historian Niall Ferguson, who also says that, in 1943, "a secret [U.S.] intelligence report noted that only the promise of ice cream and three days leave would ... induce American troops not to kill surrendering Japanese." [Source: Wikipedia +]

Ferguson states such practices played a role in the ratio of Japanese prisoners to dead being 1:100 in late 1944. That same year, efforts were taken by Allied high commanders to suppress "take no prisoners" attitudes, among their own personnel (as these were affecting intelligence gathering) and to encourage Japanese soldiers to surrender. Ferguson adds that measures by Allied commanders to improve the ratio of Japanese prisoners to Japanese dead, resulted in it reaching 1:7, by mid-1945. Nevertheless, taking no prisoners was still standard practice among U.S. troops at the Battle of Okinawa, in April–June 1945. +

Ulrich Straus, a U.S. Japanologist, suggests that frontline troops intensely hated Japanese military personnel and were "not easily persuaded" to take or protect prisoners, as they believed that Allied personnel who surrendered, got "no mercy" from the Japanese. Allied soldiers believed that Japanese soldiers were inclined to feign surrender in order to make surprise attacks.[88] Therefore, according to Straus, "Senior officers opposed the taking of prisoners on the grounds that it needlessly exposed American troops to risks..." When prisoners nevertheless were taken at Guadalcanal, interrogator Army Captain Burden noted that many times these were shot during transport because "it was too much bother to take him in". +

Ferguson suggests that "it was not only the fear of disciplinary action or of dishonor that deterred German and Japanese soldiers from surrendering. More important for most soldiers was the perception that prisoners would be killed by the enemy anyway, and so one might as well fight on." U.S. historian James J. Weingartner attributes the very low number of Japanese in U.S. POW compounds to two important factors, a Japanese reluctance to surrender and a widespread American "conviction that the Japanese were "animals" or "subhuman'" and unworthy of the normal treatment accorded to POWs. The latter reason is supported by Ferguson, who says that "Allied troops often saw the Japanese in the same way that Germans regarded Russians—as Untermenschen."

Mutilation of Japanese War Dead

Some Allied soldiers collected Japanese body parts. The incidence of this by American personnel occurred on "a scale large enough to concern the Allied military authorities throughout the conflict and was widely reported and commented on in the American and Japanese wartime press." [Source: Wikipedia +]

The collection of Japanese body parts began quite early in the war, prompting a September 1942 order for disciplinary action against such souvenir taking. Harrison concludes that, since this was the first real opportunity to take such items (the Battle of Guadalcanal), "[c]learly, the collection of body parts on a scale large enough to concern the military authorities had started as soon as the first living or dead Japanese bodies were encountered." When Japanese remains were repatriated from the Mariana Islands after the war, roughly 60 percent were missing their skulls. +

In a 13 June 1944 memorandum, the U.S. Army Judge Advocate General, (JAG) Major General Myron C. Cramer, asserted that "such atrocious and brutal policies," were both "repugnant to the sensibilities of all civilized people" and also violations of the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armies in the Field, which stated that: "After each engagement, the occupant of the field of battle shall take measures to search for the wounded and dead, and to protect them against pillage and maltreatment." Cramer recommended the distribution to all commanders of a directive ordering them to prohibit the misuse of enemy body parts. +

These practices were in addition also in violation of the unwritten customary rules of land warfare and could lead to the death penalty. The U.S. Navy JAG mirrored that opinion one week later, and also added that "the atrocious conduct of which some US personnel were guilty could lead to retaliation by the Japanese which would be justified under international law". +

Rape of Japanese Women by American Soldiers in Okinawa

U.S. soldiers raped Okinawan women during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945. Okinawan historian and former director of the Okinawa Prefectural Historical Archives Oshiro Masayasu wrote: Soon after the U.S. Marines landed, all the women of a village on Motobu Peninsula fell into the hands of American soldiers. At the time, there were only women, children and old people in the village, as all the young men had been mobilized for the war. Soon after landing, the Marines "mopped up" the entire village, but found no signs of Japanese forces. Taking advantage of the situation, they started "hunting for women" in broad daylight and those who were hiding in the village or nearby air raid shelters were dragged out one after another.” [Source: Tanaka, Toshiyuki, “Japan's Comfort Women: Sexual Slavery and Prostitution During World War II,” Routledge, 2003, p.111]

American soldier with civilians in Okinawa

There were also 1,336 reported rapes during the first 10 days of the occupation of Kanagawa prefecture after the Japanese surrender. According to interviews carried out by the New York Times and published by them in 2000, multiple elderly people from an Okinawan village confessed that after the United States had won the Battle of Okinawa three armed marines kept coming to the village every week to force the villagers to gather all the local women, who were then carried off into the hills and raped. The article goes deeper into the matter and claims that the villagers' tale - true or not - is part of a 'dark, long-kept secret' the unraveling of which 'refocused attention on what historians say is one of the most widely ignored crimes of the war': "the widespread rape of Okinawan women by American servicemen." Although Japanese reports of rape were largely ignored at the time, academic estimates have been that as many as 10,000 Okinawan women may have been raped. It has been claimed that the rape was so prevalent that most Okinawans over age 65 around the year 2000 either knew or had heard of a woman who was raped in the aftermath of the war. Military officials denied the mass rapings, and all surviving veterans refused the New York Times' request for an interview. [Source: Wikipedia +]

Professor of East Asian Studies and expert on Okinawa Steve Rabson said: "I have read many accounts of such rapes in Okinawan newspapers and books, but few people know about them or are willing to talk about them." Books, diaries, articles and other documents refer to rapes by American soldiers of various races and backgrounds. Samuel Saxton, a retired captain, explained that the American veterans and witnesses may have believed: "It would be unfair for the public to get the impression that we were all a bunch of rapists after we worked so hard to serve our country." Masaie Ishihara, a sociology professor, supports this: "There is a lot of historical amnesia out there, many people don't want to acknowledge what really happened." +

An explanation given for why the US military has no record of any rapes is that few - if any - Okinawan women reported abuse, mostly out of fear and embarrassment. Those who did report them are believed by historians to have been ignored by the US military police. A large scale effort to determine the extent of such crimes has also never been called for. Over five decades after the war has ended the women who were believed to have been raped still refused to give a public statement, with friends, local historians and university professors who had spoken with the women instead saying they preferred not to discuss it publicly. According to a Nago, Okinawan police spokesman: "Victimized women feel too ashamed to make it public." +

In his book "Tennozan: The Battle of Okinawa and the Atomic Bomb," George Feifer noted that by 1946 there had been fewer than 10 reported cases of rape in Okinawa. He explains that it was: "partly because of shame and disgrace, partly because Americans were victors and occupiers." Feifer claimed: "In all there were probably thousands of incidents, but the victims' silence kept rape another dirty secret of the campaign." Many people wondered why it never came to light after the inevitable American-Japanese babies the many women must have had. In interviews, historians and Okinawan elders said that some Okinawan women who were raped did give birth to biracial children, but that many of them were immediately killed or left behind out of shame, disgust or fearful trauma. More often, however, rape victims underwent crude abortions with the help of village midwives. +

However, American professor of Japanese Studies Michael S. Molasky argues that Okinawan civilians "were often surprised at the comparatively humane treatment they received from the American enemy." According to Islands of Discontent: Okinawan Responses to Japanese and American Power by the American Mark Selden, the Americans "did not pursue a policy of torture, rape, and murder of civilians as Japanese military officials had warned."

Image Sources: National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons; Gensuikan;

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, “History of Warfare “ by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, “The Good War An Oral History of World War II” by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016