COMFORT WOMEN

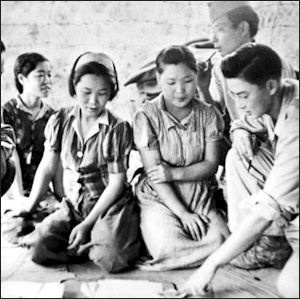

Comfort women in Myitkyina in Burma in 1944

Between 1932 and the end of World War II in 1945, an estimated 100,000 to 200,000 women served as "comfort women" (sex slaves) for Japanese soldiers in huge Japanese-run brothels. The majority came from Korea. Most of the others came from the Philippines and China. The remainder came from Indonesia, Taiwan, Thailand and Burma. Even some Dutch women in Indonesia were forced to participate. The Japanese claim there were fewer than 20,000 women in brothels used by Japanese soldiers. No definitive records have surfaced.

Comfort women is a euphemism for prostitutes enslaved to service members of the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II. According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: The so-called “comfort women” (the term is a translation of a Japanese/Korean euphemism) were sexual slaves who were often recruited by trickery and forced to serve the Japanese military in the field in Asia and the Pacific during the Pacific War. These women were drawn from throughout the Japanese empire, though many were Korean. [Source:Asia for Educators Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

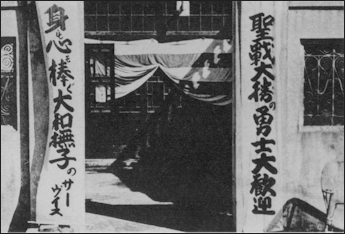

Some 2,000 "comfort stations" were set up in Manchuria, Burma, Borneo and other places in Asia, where Japanese soldiers were stationed. As of late 2015, 46 known comfort the women were still alive in South Korea. Japan’s first comfort station, Dai Salon in Shanghai, was established in 1932. A typical “comfort station” serviced 10 to 100 soldiers a day. A typical room was simply furnished with a tatami mat, futon, a washbowl and plaques with the Japanese name given to the comfort woman kept there. Outside, welcome banners for soldiers were sometimes hung. Korean-born, New York-based Lee Chang-jin, creator of the “Comfort Women Wanted” art exhibit, said: “One of the women said they used to get raped by 50 soldiers a day.”

A number of Japanese soldiers have come forward and admitted their role in forcibly taking women and girls on orders of the military. In 1993, documents found in the archives of Japan’s Defense Ministry indicated that the military was directly involved in running the brothels. Reasons offered for running the brothels were; 1) they prevented Japanese soldiers from raping women and committing sex crimes in occupied areas: 2) they prevented the spread of venereal diseases (prostitutes had regular medical check-ups); and 3) they prevented the loss of military secrets by limiting the women soldiers and officers were exposed to.

RELATED ARTICLES IN THIS WEBSITE: PEARL HARBOR, JAPANESE VICTORIES AND OCCUPATION IN SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com; BEGINNING OF WORLD WAR II IN ASIA AND THE PACIFIC factsanddetails.com; PEARL HARBOR AND EYEWITNESS ACCOUNTS OF THE ATTACK factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE INVASION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA factsanddetails.com; JAPAN DEFEATS THE BRITISH AND TAKES MALAYA AND SINGAPORE factsanddetails.com; JAPAN TAKES THE PHILIPPINES: MACARTHUR, CORREGIDOR AND THE BATAAN DEATH MARCH factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF SOUTHEAST ASIA AND THE PACIFIC DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com INTERNED JAPANESE AMERICANS DURING WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; FORCED LABORERS IN ASIA IN WORLD WAR II AND THE DEATH RAILWAY IN THAILAND AND BURMA factsanddetails.com; BRUTAL TREATMENT OF POWS BY THE JAPANESE AND ATROCITIES BY U.S. SOLDIERS factsanddetails.com

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “Comfort Woman” by Nora Okja Keller Amazon.com; “The Comfort Women: Japan's Brutal Regime of Enforced Prostitution in the Second World War” by George Hicks Amazon.com; “Chinese Comfort Women: Testimonies from Imperial Japan's Sex Slaves (Oxford Oral History Series) by Peipei Qiu , Su Zhiliang, et al. Amazon.com; “Comfort Woman: A Filipina's Story of Prostitution and Slavery under the Japanese Military” by Maria Rosa Henson , Sheila S. Coronel, et al. Amazon.com

How Women Became Comfort Women

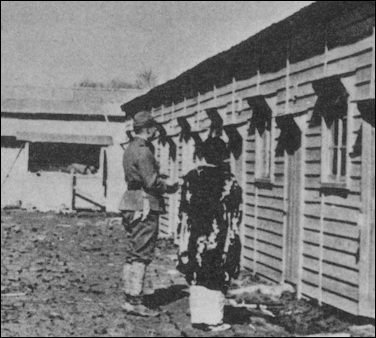

Registration of comfort women

Women between 11 and 40 served as sex slaves. Many of the women were kidnapped and raped. Others were tricked and defrauded. Some women claim they were taken from their villages at gunpoint and told they were being taken to work in factoriesThey often had sex with between 20 and 50 men a day in dirty barracks and bare wooden rooms with a sign over the door that read "total heart and physical service by devoted girls." One Korean woman who was taken to a military brothel in Borneo said she was forced to have brutal sex as often as 20 times a day.

Ho Yi wrote in the Taipei Times, “One victim is Chen Lien-hua from Taiwan, who at age of 19 was lured into prostitution by the false promise of a job abroad that could help support her poor family. According to the information compiled by the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, which has worked with survivors in Taiwan since 1992, women were sometimes directly recruited to be comfort women, but were more often the victims of deception or coercion. “They were usually tricked and lied to, believing that they were to work as nursing assistants overseas. Some were recruited by the district offices. You couldn’t say no to the recruitment. It was mandatory,” says Kang Shu-hua, executive director of Taiwan-based foundation that helps comfort women. [Source: Ho Yi, Taipei Times, December 29, 2013 +++]

Korean survivor Lee Oak-seon said she was kidnapped on the street and sent to China at the age of 16. Many Korean girls, some as young as 11, endured similar fates. Those who dared to disobey were tortured and killed at comfort stations. +++

Japanese Government Involvement in the Comfort Women Brothels

The brothels were either run by or set up with the cooperation of the Japanese military. . Jake Adelstein wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “Historical documents unearthed in the 1990s, along with accounts from soldiers and victims, suggested that military authorities had a direct role in working with contractors to forcibly procure women to work in brothels. Nobutaka Shikanai, the former president of Japan’s most conservative paper, the Sankei Shimbun, and an officer in the Imperial Japanese Army’s accounting department during the war, has acknowledged the government’s role in building wartime sex-trafficking networks.[Source: Jake Adelstein, Los Angeles Times, December 28, 2015 ***]

“When we procured the girls, we had to look at their endurance, how used up they were, whether they were good or not,” he was quoted as saying in a book of interviews and memoirs, “The Secret History of the War.” “We had to calculate the allotted time for commissioned officers, commanding officers, grunts, how many minutes. We also had to fix prices according to rank. There was even a prospectus we learned in [military] accounting school.”

Comfort Women in Korea

One former comfort woman and slave laborer told the Korean Herald that she was 15 when her Japanese teacher forced her to join a group of Korean girls on a ship bound for Japan. "There was no one who could reject an order from a Japanese teacher," she said. "I was forced to work at a military weapons factory under very harsh circumstances." Suffering from extremes exhaustion and hunger, she tried to escape from the factory but was caught and raped by a Japanese soldier. After that she was forced to serve two years as a comfort woman. "I was raped, and raped and raped...by Japanese military forces," she said. When the war ended she returned to South Korea, and spent most of her life drifting from city to city performing menial jobs. She had difficulty saving money and getting ahead because she spent most of her "money visiting hospitals to cure venereal diseases" which she "contacted from the Japanese soldiers."

Choe Sang-Hun wrote in the New York Times: "The hairy middle-aged man held down my arms and legs," said one of the women, Yun Soon Man, describing the night a Japanese soldier violated her 14-year-old body in a military-run brothel. Yun, 77, shut her eyes and trembled with both fists clenched as her mind traveled back to the three-story brothel in southern Japan, up to the second floor, down the hall to a third room where she and another Korean woman wearing nothing but kimonos were assigned to the room's two beds to provide "comfort" for Japanese soldiers. When she opened her eyes with a sigh, she raised her crooked left arm and pointed at her bared teeth. "You see I had a strong set of teeth. I bit his ear with all my strength left," she said. "The man screamed and went wild. He grabbed my arm and snapped it until it broke." [Source: Choe Sang-Hun, New York Times, October 15, 2005]

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: As a teenager a former comfort woman named Kang recalls “she was lured from her home by Japanese soldiers who offered her caramel candy....Without prompting, Park Ok-ryun, 86, launches into an account of how, as an 18-year-old, she was abducted by two Japanese soldiers. She and a friend had gone to a stream to get water. "Don't cry," she remembers the soldiers saying. "If you go with us, you can get some nice food and nice clothes." Park grabs a listener's arm. "I was thrown into the truck and covered with a red-and-blue fabric," she says. She begged to be released, explaining that she had to return home to make dinner. "But they said, 'Jackass, stop nagging,' and kicked me," she says, showing a jagged scar on her leg. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, April 30, 2009]

Story of Kim Tokchin

comfort station entrance

According to Columbia University’s Asia for Educators: The story of Kim Tokchin has many elements common to the experiences of “comfort women,” including the initial promise of factory employment, the role of recruiting agents (Korean in this case), the initial rape by a Japanese officer, and the arrangement of the brothel in which she was forced to serve. [Source: Asia for Educators Columbia University afe.easia.columbia.edu ]

“It was the middle of January or perhaps a little later, say the beginning of February, 1937. I was 17 years old. I heard girls were being recruited with promises of work in Japan. It was said that a few had been recruited not long before from P’y.ngch’on where we had lived with my uncle. I wished that at that time I had been able to with them, but I suddenly heard a Korean man was in the area again recruiting more girls to work in the Japanese factories. I went to P’yongch’on to meet him and promised him I would go to Japan to work. He gave me the time and place of my departure and I returned home to ready myself to leave. In those days people were rather simple, and I, having had no education, didn’t know anything of the world. [Source: “True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women,” edited by Keith Howard and translated by Young Joo Lee (London: Cassell, 1995), 42.

“All I knew — all I thought I knew — was that I was going to work in a factory to earn money. I never dreamed that this could involve danger. … We arrived at Kunbuk station and transferred to a train. It was a public slow train, and traveled slowly down to Pusan, where we boarded a boat. The man who had brought us this far left us, and a Korean couple who said their home was in Shanghai took charge of us. The boat was huge. It had many decks, and we had to climb down many lights of stairs, right to the bottom of the boat to find our bunks. It was a ferry and took many other passengers. The crew brought us bread and water, and we sailed to Nagasaki. At Nagasaki, a vehicle resembling a bus came and took us to a guest.house. From that moment on we were watched by soldiers. I asked one of them: “Why are you keeping us here? What kind of work are we going to do?” He simply replied that he only followed orders. On the first night there I was dragged before a high.ranking solder and raped. He had a pistol. I was frightened at seeing myself bleed and I tried to run away. He patted my back and said that I would have to go through this experience whether I liked it or not, but that after a few times I would not feel so much pain. We were taken here and there to the rooms of different high.ranking officers on a nightly basis. Every night we were raped. On the fifth day, I asked one of the soldiers; “Why are you taking us from room to room to different men? What is our work? Is it just going to be with different men?” He replied: “You will go wherever orders take you. And you will know what your job is when you get there.” We left Nagasaki after a week of this grueling ordeal.

“Led by our Korean guides, we boarded another boat for Shanghai. … There was a truck waiting for us at the pier, which whisked us away. There were not rail.tracks, and no buses or taxis to be seen. We passed through disordered streets and arrived in a suburban area. There was a large house right beside an army unit, and we were to be accommodated there. The house was pretty much derelict and inside was divided into many small rooms. There were two Japanese women and abut 20 Koreans there, so with the 30 of us who had arrived from Uiryong there were about 50 women in total. The two Japanese were said to have come from brothels. They were 27 or 28, about ten years older than all the Koreans. The soldiers preferred us Korean girls, saying we were cleaner. Those who had arrived before us came from the south.western provinces of Cholla and the central provinces of Ch’ungch’ong and were of similar age to us. Those of us who had traveled together kept ourselves very much to ourselves. I was called “Langchang” there. From the 50 of us, excluding those who were ill or had other reasons, 35 girls on average worked each day. … We rose at seven in the morning, washed and took breakfast in turns. Then from about 9 o’clock the soldiers began to arrive and form orderly lines. From 6 o’clock in the evening highranking officers came, some of whom stayed overnight. Each of us had to serve an average of 30 to 40 men each day, and we often had no time to sleep. When there was a battle, the number of soldiers who came declined. In each room there was a box of condoms which the soldiers used.

“There were some who refused to use them, but more than half put them on without complaining. I told those who would not use them that I had a terrible disease, and it would be wise for them to use a condom if they didn’t want to catch it. Quite a few would rush straight to penetration without condoms, saying they couldn’t care less if they caught any diseases since they were likely to die on the battlefield at any moment. On such occasions I was terrified that I might actually catch venereal disease. After one use, we threw the condoms away; plenty were provided.

Comfort Women in Cambodia and the Philippines

sex slave memorial in Manila

Filipino women were forced into sexual slavery as comfort women for Japanese soldiers during the Japanese occupation of the Philippines. Some half Japanese children in the Philippines were the result of unions between these women and Japanese soldiers.

One Filipina told William Branigin of the Washington Post that she was abducted from her village when she was only 14 and raped day and night for a week before she escaped. Another said she was raped repeatedly for three weeks after being abducted in Manila when she was 18.

There have been demonstrations in Manila on the comfort woman issue, some of them by Japanese-Filipino children who want child support from their Japanese "dead beat dads." The Japanese government didn’t admit until 1992 that comfort women brothels existed in the Philippines. The next year they admitted the brothels were organized by the military but said there was no evidence that women were forced to work in them. In 1994, Japanese apologized, offered $1 billion compensation payment to several nations, and built a vocational training center in Manila.

The most well-known comfort woman is South Korea is Grandma Hun, a woman who was discovered in Cambodia in 1997 when she 73 years old. She said she had been taken to Cambodia when she was a teenager and eventually became the mistress of a Japanese soldier who fathered her child. The soldier eventually abandoned her in Cambodia, where she married a Cambodian man and had two children. She was survived the Khmer Rouge reign of terror and was brought back to Korea after being discovered by a Cambodian newspaper.

Comfort Women in Indonesia and East Timor

Jan Ruff O’Herne, a Dutch woman who spent her childhood in Indonesia, became a Comfort woman. In a film called “Comfort Women Wanted” made Korean-born, New York-based Lee Chang-jin, O’Herne said: ““The first night we didn’t know what we were there for. We thought that perhaps we would work there. We were so scared ... The next night we realized we were in a brothel for the sexual pleasure of the Japanese officers ... We were dragged back and it started again. To think that this is going to happen every night. I can never describe the fear every day when it starts to get dark. Fear, all over your body. There is nothing you can do about it.” In 2007, O’Herne and other victims went to the U.S. House of Representatives, requesting that the US demand the Japanese government’s acknowledgment of the sexual enslavement of comfort women. [Source: Ho Yi, Taipei Times, December 29, 2013]

Stephanie Coop wrote in the Japan Times, “Ines de Jesus was a young girl during World War II when she was forced to become a sex slave, or “comfort woman,” for Japanese troops in the then Portuguese colony of East Timor. By day, de Jesus carried out various kinds of menial labor, and each night was raped by between four to eight Japanese soldiers at a so-called comfort station in Oat village in the western province of Bobonaro. While horrific, de Jesus’ experience with sexual abuse under military occupation is by no means unusual among East Timorese women, as a special exhibition at the Women’s Active Museum on War and Peace in Tokyo’s Shinjuku Ward makes clear. [Source: Stephanie Coop, Japan Times, December 23, 2006 |::|]

Twenty-one comfort stations were identified by a team led by Kiyoko Furusawa, an associate professor of development and gender studies at Tokyo Woman’s Christian University. “Japanese landed in East Timor in February 1942 to oust a contingent of Australian troops that had entered the neutral territory the previous December, it ordered “liurai” (traditional kings) and village heads to supply women to serve the troops. Some of those who refused to comply were executed. “Women enslaved in comfort stations were forced to serve many soldiers every night, while others were treated as the personal property of particular officers,” she said. “Some women were specifically targeted for enslavement because their husbands were suspected of aiding the Australian troops. “As well as being physically and psychologically traumatized by the sexual abuse, the women were also made to work at tasks such as building roads, cutting wood, growing and preparing food, and doing laundry during the day, so they were constantly exhausted. They were also forced to dance and were taught Japanese songs to entertain soldiers,” Furusawa said. |::|

“Comfort women received no payment for their work and little or no food, she added. Family members either brought food to the comfort stations or the women were sent home to obtain it. There was little likelihood of women trying to escape at such times, she explained. “There were around 12,000 Japanese troops in a country with a population of only about 463,000, so the whole island was like an open prison. There was nowhere for the women to go, and at any rate, they were terrified about reprisals against their families if they did try to escape.” |::|

Comfort Women in Taiwan

Comfort station

In Taiwan, over 2,000 women are believed to have been comfort women. According to Kang Shu-hua, executive director of the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, of the 58 former comfort women the foundation has found in Taiwan and worked with since 1992, only five were still alive in 1992.

Ho Yi wrote in the Taipei Times, “One victim is Chen Lien-hua from Taiwan, who at age of 19 was lured into prostitution by the false promise of a job abroad that could help support her poor family. According to the information compiled by the Taipei Women’s Rescue Foundation, women were sometimes directly recruited to be comfort women, but were more often the victims of deception or coercion. “They were usually tricked and lied to, believing that they were to work as nursing assistants overseas. Some were recruited by the district offices. You couldn’t say no to the recruitment. It was mandatory,” says Kang Shu-hua, executive director of the foundation, which organized the Comfort Women Wanted exhibition. [Source: Ho Yi, Taipei Times, December 29, 2013]

Comfort Women After World War II

Many of the Korean "comfort women" were in their teens when they were captured and decades after the war they were ostracized and humiliated by their own people for the experiences that had been imposed on them. After the war many former comfort women were crippled from syphilis and beatings, psychologically scared from their ordeal and shamed for life. Those that survived were ostracized and humiliated by their own people when they returned to their homes after World War II.

Japan denied the existence of comfort until 1993, after Chou University history professor Yoshiaki Yoshima went public with documents from government archives that provided details of government complicity in the establishment of "comfort stations" to reduce the number of rapes on local women. Yoshima told Time, "The government is trying to cover up evidence that it broke international law. Otherwise it would be required to pay individual compensation to victims."

In 2009, John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Now time is running out for the halmoni, or Korean grandmothers. About 150,000 to 200,000 Korean women served as Japanese sex slaves, most living out their lives in humiliated silence. When activists brought the issue to light in the early 1990s, officials sought out survivors. While many were too ashamed to come forward, officials registered 234 women. Ninety-three are still alive, according to a nonprofit group that looks after them. [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, April 30, 2009]

Japan’s Efforts to Address the Comfort Women Issue

Comfort women in the Andaman Island

John M. Glionna wrote in the Los Angeles Times: “Japan's response has been mixed. After the war, the government maintained that military brothels had been run by private contractors. But in 1993, it officially acknowledged the Imperial Army's role in establishing so-called comfort stations. Conservatives in the political establishment still insist there is no documentary evidence that the army conducted an organized campaign of sexual slavery — a contention challenged by many researchers.” [Source: John M. Glionna, Los Angeles Times, April 30, 2009]

Jake Adelstein wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “The legal controversy over former comfort women began in late 1991 when a group of South Korean women filed a lawsuit with a Tokyo court, demanding that the Japanese government formally apologize and compensate them for their suffering. During a visit to Seoul in January 1992, then-Prime Minister Kiichi Miyazawa officially apologized to South Koreans for the suffering inflicted upon comfort women by the Japanese army. In 1993, Japan issued a formal apology for the wartime network of brothels and frontline stations that provided sex for the military and its contractors. [Source: Jake Adelstein, Los Angeles Times, December 28, 2015 ***]

Japan’s more conservative politicians have criticized the 1993 apology, despite substantial evidence that the Japanese government was involved in trafficking the women. In June 1995, the Japanese government announced details to creating a special fund to provide allowances to former comfort women. However, many South Koreans criticized the fund — which consisted of money raised from private donors — for glossing over the Japanese government’s role in perpetrating wartime atrocities. The fund was dissolved in 2007.

Japan: No Documents Confirm Military Coerced Comfort Women

Kyodo, the Japanese news service, reported in 2016: Japan has found no documents confirming that the “comfort women” were forcefully recruited by military or government authorities, a Japanese envoy told a U.N. panel. Deputy Foreign Minister Shinsuke Sugiyama made that claim during a session in Geneva of the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women. The belief that women were forced into sexual servitude is based on the false accounts of the late Seiji Yoshida, Sugiyama said. Yoshida claimed to have forcibly taken women from the island of Jeju, then under Japanese colonial rule and now part of South Korea, and forced them into sexual labor for the Japanese military before and during World War II. The Asahi Shimbun in 2014 retracted articles that reported Yoshida’s accounts, Sugiyama noted. [Source: Kyodo, February, 2016]

According to the Yomiuri Shimbun, : The government has admitted the Imperial Japanese Army's involvement in brothels, saying that "the then Japanese military was, directly or indirectly, involved in the establishment and management of the comfort stations and the transfer of comfort women." The "involvement" refers to giving the green light to opening a brothel, building facilities, setting regulations regarding brothels, such as fees and opening hours, and conducting inspections by army doctors. [Source: The Yomiuri Shimbun, April 1, 2007]

“However, the government has denied that the Japanese military forcibly recruited women. On March 18, 1997, a Cabinet Secretariat official said in the Diet, "There is no evidence in public documents that clearly shows there were any forcible actions [in recruiting comfort women]." No further evidence that could disprove this statement has been found.

“The belief that comfort women were forcibly recruited started to spread when Seiji Yoshida, who claimed to be a former head of the mobilization department of the Shimonoseki branch of an organization in charge of recruiting laborers, published a book titled "Watashi no Senso Hanzai" (My War Crime) in 1983. Yoshida said in the book that he had been involved in looking for suitable women to force them into sexual slavery in Jeju, South Korea. "We surrounded wailing women, took them by the arms and dragged them out into the street one by one," he said in the book. But researchers concluded in the mid-1990s that the stories in the book are not authentic.

Comfort women

Comfort Women Compensation

In 1993, the Japanese government formally apologized to the women described as comfort women. Since then, the government stances seems to have been to admit moral but no legal responsibility. A private fund was set up to compensate comfort women, and two Japanese prime ministers wrote formal letters of apology to women who received the payments. Some women found this arrangements unacceptable and refused to accept compensation. Japanese courts have recognized that women from Korea were brought to Japan under false pretenses and forces to work in military factories but dismissed claims for damages and compensation, citing the 1951 U.S.-Japan San Francisco Treaty and the 1965 compensation rights treaty between Japan and South Korea.

In September 1994, the Japanese government announced it would spend US$1 billion over the next 10 years on a "Peace, Friendship and Exchange Initiative" in Asian counties as way of atoning for hardships endured by "comfort women" before and during World War II. A Japanese cabinet secretary apologized for the actions that "stained the honor and dignity of many women." Japan helped established the Asia Women's Fund to raise money from businesses to compensate comfort women from South Korean and Taiwan. The women were scheduled to receive $23,000 a piece over five years while those from the Philippines were scheduled to receive $9,200. The difference in payments was due to the fact that the Philippines has a lower cost of living. The fund had trouble raising money. Many former comfort women said that the "initiatives" were not nearly enough and demanded to be compensated directly. In Seoul, South Korean women hurled eggs at the Japanese embassy.

In April 1998, the South Korean government said it would end its effort to win compensation from the Japanese government on the comfort women issue. Instead the South Korean government promised to pay 152 registered comfort women in South Korea $22,700, which would be supplemented by $4,700 from victims rights organizations. A poll found 70 percent of Japanese believe Japan didn't pay enough compensation for victims of war crimes.

In 2000, a Tokyo District Court dismissed a case brought by 46 former sex slaves from the Philippines who accused Japan of war crimes and crimes against humanity. In 2001, a reparations claim by South Korean women who had been held as sex slaves failed in a Hiroshima High Court on the grounds that coerced sex was not illegal when it was carried out. The Japanese government fears that acknowledging the comfort women will open it up to claims from other victims — British prisoners of war, Koreans forced to work in Japanese factories or Koreans force to fight against the US army. The Japanese defense is that: 1) even if the women were held involuntarily there was no law against that at the time; 2) if coerced sex was illegal these laws did not apply in military-occupied territories; and 3) whatever misconduct occurred was settled by peace treaties at the end of the war. The Japanese have stood by these arguments even though it has signed four treaties barring forced labor and sexual trafficking of women.

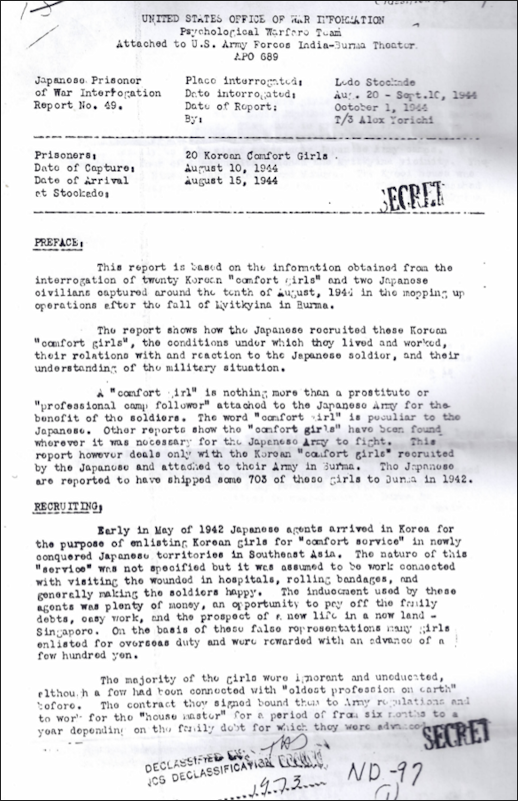

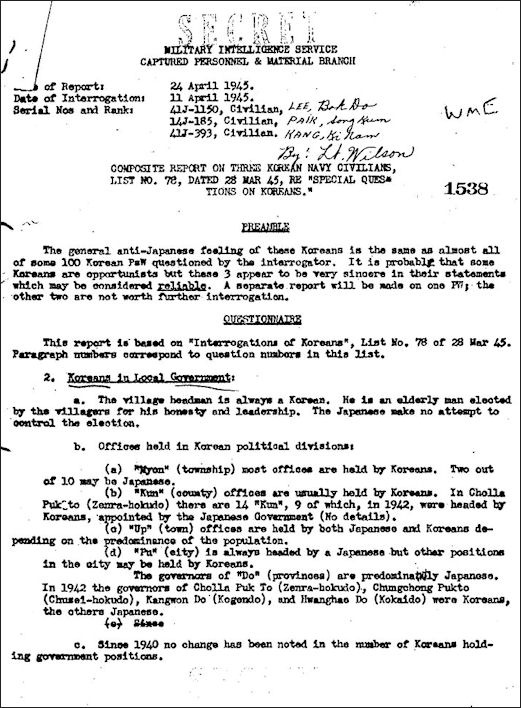

US document related to comfort women

South Korea and Japan Make Deal on Comfort Women

In December 2015, Japan and South Korea reached a breakthrough agreement to “irreversibly” end to the controversial “comfort women” issue which refers to women — many of them Korean — forced to work in Japan’s wartime brothels. The issue has stirred animosity between the neighbors for decades.Jake Adelstein wrote in the Los Angeles Times, “After a meeting in Seoul, the two countries’ foreign ministers said Japan will contribute 1 billion yen ($8.3 million) to a fund for the surviving elderly comfort women; in return, South Korea will refrain from criticizing Japan over the issue and work to remove a statue representing the victims from in front of the Japanese Embassy in downtown Seoul. [Source: Jake Adelstein, Los Angeles Times, December 28, 2015 ***]

“South Korean Foreign Minister Yun Byung-se told reporters that the issue would be “finally and irreversibly resolved” if Japan fulfilled its obligations.The agreement dovetails with the United States’ geopolitical priorities. Washington has long hoped for improved relations between its two major Asian allies to counterbalance an increasingly aggressive China and the erratic behavior of North Korea. ***

“South Korean President Park Geun-hye and Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe pledged to use the agreement to improve bilateral ties. Abe told reporters in Tokyo that Japan apologizes to the women for their pain; yet he added that future Japanese generations should not have to keep on doing so. “We should not allow this problem to drag on into the next generation,” he said, echoing remarks he made marking the 70th anniversary of the end of World War II on Aug. 15. “From now on, Japan and South Korea will enter a new era.” ***

“The agreement was unexpected, especially under the conservative Abe administration. Until quite recently, Abe has been critical of attempts by previous administrations to acknowledge Japanese military involvement in the enslavement of the comfort women before and during World War II. Critics have called him a historical revisionist, but he appeared to be echoing a widespread belief among Japanese nationalists that many of the Korean women were sold by their families, or worked willingly as prostitutes. In 2007, Abe said there was “no evidence to prove there was coercion.” ***

In April 2016, Abe and South Korean President Park Geun-hye confirmed the importance of implementing the December 2015 agreement to settle the comfort women issue. Kyodo reported: “Abe and Park met one-on-one in Washington on the fringes of the Nuclear Security Summit, following their high-profile meeting in November, the first since the two leaders took office in 2012 and 2013, respectively. Abe was quoted by a Japanese official as telling Park that he is willing to follow up on the deal to help the women, euphemistically called “comfort women,” though some problems remain surrounding the matter in both countries. Park said South Korea intends to implement the deal in a sincere manner, according to Deputy Chief Cabinet Secretary Koichi Hagiuda. Tokyo has promised to provide the money to a foundation to be set up by the South Korean government. Seoul, however, has yet to create such a body as many former comfort women have criticized the Tokyo-Seoul deal, calling on Japan to admit legal responsibility for compensation. The deal was clinched without any consultation with surviving victims.”[Source: Kyodo, April 1, 2016]

Korean Professors Imprisoned and Fined for “Insulting” Comfort Women

In November 2018 a district court in Gwangju sentenced former Sunchon National University professor Park Yu-ha to six months in prison for defaming the comfort women, overturning the defendant’s appeal and reinforcing the original sentence once again. Lee Tae-hee wrote in the Korea Herald: “The court ruled that the professor insulted the sex slaves with remarks such as, “(The comfort women) were taken for sexual slavery, or they voluntarily followed, because they were ‘seductive.’ In my opinion, they probably had a clear idea what they had to do.” The professor reportedly made the controversial remarks during a university lecture on April 26, 2017. [Source: Lee Tae-hee, Korea Herald, November 15, 2018]

“A few months after the incident on Sept. 26 of the same year, human rights group Sunchon Nabi accused the professor of spreading false information and defaming the comfort women. After the first court ruling the professor appealed, saying that his words were not ill-intended. The defendant said that “considering the overall context of the class, I did not intend to say that the victims voluntarily participated in sexual slavery.” The Gwangju High Court dismissed the appeal Thursday and issued a six-month prison term. The court said, “In spite of his position as a national university professor, the defendant committed a serious crime of spreading false information and defaming the comfort women. Also, there had been no attempt to repair the damage.” After the incident, Sunchon National University officially expelled the professor from his position on Oct. 12, 2017.

US document on comfort women

On a different professor, Andrew Salmon of Forbes wrote: A South Korean professor who has questioned key elements of an explosively emotive national narrative has been ordered by a Seoul court to pay nine former “comfort women” KRW10 million (US$8,262) each for defaming them in a book. It was the second court action against Park Yu-ha, the author of 2013’s “Comfort Women of Empire,” who was, in February 2015, ordered to redact 34 passages in the book. The latest judgment, found her guilty, in a civil case, of defaming surviving Korean “comfort women“ who toiled in Japanese military brothels during World War II. [Source: Andrew Salmon, Forbes, January 14, 2016]

Park, a professor of Japanese literature at Seoul’s Sejong University and a former resident of Japan wrote a previous book, “For Reconciliation,” designed, she told foreign reporters last month, to bring Japan and Korea closer. “Comfort Women of Empire,” she said, was written to provide “different perspectives” on the issue. Those perspectives – drawn from research in both Korea and Japan – have generated a storm of controversy in Korea where the comfort woman issue represents hair-trigger sensitivities.

“Park suggests that there were different comfort women had a range of experiences; not all were forced, tricked or coerced into service; some even volunteered to do work in military brothels as their patriotic duty. Her research also indicates that the recruiters of comfort women were Japanese and Korean “agents” engaged in human trafficking, rather than government officials. Widespread opinion in Korea, on the other hand, holds that they were forcibly recruited or kidnapped by the Japanese Imperial Army or police. Park says some comfort women were well paid. In Korea, and elsewhere, they are widely portrayed as “sex slaves.” She also questions a vaguely sourced figure of “200,000 comfort women, mostly Koreans,” that is widely quoted in Korean and international media. She stated her belief that the actual number of was closer to 50,000.

“Park’s “perspectives” have not been welcomed in Seoul. The Seoul Eastern District Court said Wednesday that the findings in her book were invalidated by previous research and governmental statements, and turned down her plea for academic freedoms. “Considering the fact that the victims are still alive, her right to academic freedom does not supersede that of the victims’ right to dignity,” the court said, according to local news reports. The court indicted Park for defamation last November, and reached a swift verdict on January 13. By contrast, a landmark libel case bought to a British court by Holocaust denier David Irving lasted from September 1996 to April 2000 and the court only found against Irving after hearing detailed evidence from an international team of historians.”

‘Comfort Women’ Groups Accused of Embezzling Millions

In May 2020, a support group for South Korean comfort women were accused of embezzling millions of dollars worth donations meant for the comfort women. Julian Ryall wrote in The Telegraph: “A manager and six staff at the House of Sharing have claimed that around $5 million in donations has been siphoned off for unrelated projects and that the residents of the facility do not receive the care that they require. [Source: Julian Ryall, The Telegraph, May 20, 2020]

“The accusations come just days after the other major support organisation for former comfort women was similarly accused of embezzling donations. Those allegations have lead to demands for an official investigation into Yoon Mee-hyang, a former head of the Korean Council for Justice and Remembrance for the Issues of Military Sexual Slavery by Japan. Ms Yoon was elected as a member of the ruling Liberal Party to the South Korean parliament in last month’s elections, but opposition parties are now claiming that the organisation and Ms Yoon personally exploited surviving comfort women and embezzled donations.

“Korean media have reported that Ms Yoon is suspected of pocketing donations and government subsidies and using those funds for her own purposes. One outlay that has attracted attention was the payment of more than £22,000 to a bar for an event allegedly to promote the council’s work. The operator of the bar has stated, however, that the cost of the event was only £6,440 and that it returned more than £3,500 as a donation.” Further questions are being raised over a large house that was purchased in 2013 with the organisation’s funds to serve as a mountain retreat for the former comfort women. According to the reports, the women never visited the property and the organisation paid Ms Yoon’s father nearly £50,000 over six years to live at the house as a “caretaker”.”

Image Sources: Japan Focus; National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons;

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, “Eyewitness to History “, edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, “History of Warfare “ by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, “The Good War An Oral History of World War II” by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated December 2020