BURMA ROAD

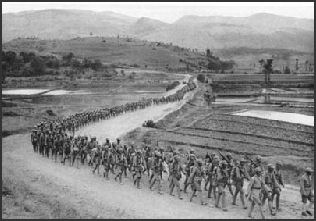

Chinese troops march on Ledo Road What is called the Burma Road was actually two roads: 1) the roughly 600-mile-long Burma Road, built in 1937 and 1938 between Lashio, Burma and Kunming, China under Chiang kai-shek to bring supplies through a backdoor of China after the Japanese invaded China; 2) and the roughly 500-mile-long Ledo Road (See Below). The roads cost 1,133 American lives, roughly a man a mile.[Source: Donovan Webster, National Geographic, November 2003]

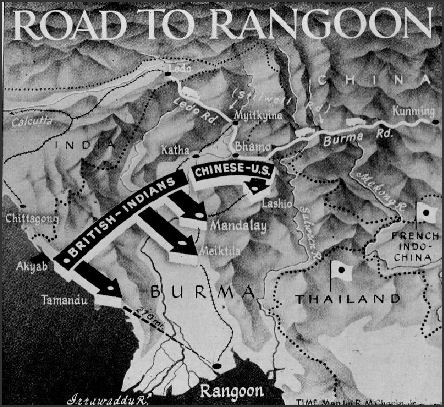

The straight line distance from Ledo to Kunming is about 460 miles. The Burma and Ledo Roads, built through some of the world’s most difficult terrain in India, Burma and China, covered more than twice that distance and hooked southward to avoid the Himalayas. The idea was ultimately to use the roads for an invasion of China and from China an invasion of Japan. Churchill called the entire project “an immense, laborious task, unlikely to be finished, until the need for it had passed.” The project was not completed until just six months before the war ended.

The Burma Road was the major overland supply route to China after the Japanese took over much of coastal China in 1937 and 1938 and blockaded its seaports. It was built at a break-neck pace, often by Chinese laborers forced to work for the Nationalists for two years without pay. When it was finished it was little more than a supply track that could only be used by trucks in the dry season.

The Burma Road was built by 160,000 Chinese laborers with virtually no machinery. One worker, who worked on the road between Ruili in Burma and Kunming in China told National Geographic, “It was not easy. I was a boy. In 1937 the engineers came through with stakes, marking where they wanted the roadway. We worked seven days a week, from sunrise to sunset.”

LINKS IN THIS WEBSITE: JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE COLONIALISM AND EVENTS BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE OCCUPATION OF CHINA BEFORE WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; SECOND SINO-JAPANESE WAR (1937-1945) factsanddetails.com; RAPE OF NANKING factsanddetails.com; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II factsanddetails.com; FLYING THE HUMP AND RENEWED FIGHTING IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; JAPANESE BRUTALITY IN CHINA factsanddetails.com; PLAGUE BOMBS AND GRUESOME EXPERIMENTS AT UNIT 731 factsanddetails.com

Book: The Burma Road by Donovan Webster (Macmillan, 2004)

Good Websites and Sources on China during the World War II Period: Wikipedia article on Second Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ; Nanking Incident (Rape of Nanking) : Nanjing Massacre cnd.org/njmassacre ; Wikipedia Nanking Massacre article Wikipedia Nanjing Memorial Hall humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre ; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/China ; Good Websites and Sources on World War II and China : ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; U.S. Army Account history.army.mil; Burma Road book worldwar2history.info ; Burma Road Video danwei.org

Good Websites and Sources on China during the World War II Period: Wikipedia article on Second Sino-Japanese War Wikipedia ; Nanking Incident (Rape of Nanking) : Nanjing Massacre cnd.org/njmassacre ; Wikipedia Nanking Massacre article Wikipedia Nanjing Memorial Hall humanum.arts.cuhk.edu.hk/NanjingMassacre ; CHINA AND WORLD WAR II Factsanddetails.com/China ; Good Websites and Sources on World War II and China : ; Wikipedia article Wikipedia ; U.S. Army Account history.army.mil; Burma Road book worldwar2history.info ; Burma Road Video danwei.org

RECOMMENDED BOOKS: “The Burma Road” by Donovan Webster(Macmillan, 2004) Amazon.com; “The Imperial War Museum Book on the War in Burma, 1942-1945" by Julian Thompson (Pan, 2003) Amazon.com; “Burma: The Longest War 1941-1945" by Louis Allen Amazon.com; “Famine, Sword, and Fire: The Liberation of Southwest China in World War II” by Daniel Jackson Amazon.com; “Clash of Empires in South China: The Allied Nations' Proxy War with Japan, 1935-1941 by Franco David Macri Amazon.com; “Chinese Civil War: A History from Beginning to End” Amazon.com “Chiang Kai-shek versus Mao Tse-tung: The Battle for China 1946–1949" (Images of War) by Philip Jowett Amazon.com “China's Civil War: A Social History, 1945–1949" by Diana Lary (Author) Amazon.com “China's World War II, 1937-1945" by Rana Mitter (Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2013) Amazon.com; Chiang Kai-Shek and the Struggle for Modern China" by Jay Taylor Amazon.com

Ledo Road

The Ledo Road was built between 1942 and 1945 between Ledo in India and the Burma Road. U.S. Gen. Joseph "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell, the abrasive commander of Allied troops in the region, insisted the project would work.. Gen. Lewis Pick was the chief engineer of the Ledo Road. Known to some as “Pick’s Pike,” he told his engineers in 1943: “The road is going to be built---mud, rain, and malaria be damned!” It is sometimes called the Stilwell Road.[Source: Los Angeles Times, December 30, 2008]

The U.S. spent almost $149 million to build the Ledo Road at the request of Nationalist Chinese leader Chiang Kai-shek. It took a little over two years to build. It was roughly 500 miles long and opened up a new supply route, as well as an oil pipeline, from India to China. Military strategist felt the road was necessary to supply China in the war. More than 28,000 Americans and 35,000 Asian workers participated in the project. Not long after the thankless job was done, two atomic blasts finished the war with Japan, and a hard-won passage that soldiers called "the Big Snake" was abandoned to the rain forest.

Construction of the Ledo Road began in 1942. The first true bridge was built over the Khtang Nall in northeastern India In October 1943, American-trained Chinese divisions entered Burma from Assam, India and drove down the Japanese road from the Hukawag Valley in northern Burma. In February 1945, Gen. Pick led a convoy into Kunming.

In 15 months construction battalions moved 13.5 million cubic yards of earth to cut the roadbed. the New York Times correspondent Tillman Durbin said there was enough dirt to build a 10-foot-high, three-foot-think wall between New York City and San Francisco.

Building the Ledo and Burma Roads

William Stronks wrote in a letter to National Geographic : “I was an officer in the 1340th Engineering Battalion. With very limited equipment we built every pile-driven bridge from Ledo to Myitkyina. Chinese troops were brought in to cut down trees and hand-hew them into 12-inch-by-12-icnh timbers. We used elephants brought in from India to drag the timbers to the bridge site, using a portable generator, we worked day and might. We lived like gypsies and moved our camps from bridge to bridge—often before any bridge was available.”

An engineer and shovel operator who worked the project told National Geographic, “It was crazy, and it was miserable. Every day was the same. Up at dawn, sweat and work until dark. It was so hot sometimes, where we’d lay concrete, it would be dry in an hour. We’d cut a stretch of road over some jungle mountain, and the monsoon would wash it out. But we kept going. We had no choice.”

Obstacles included landslides, man-eating tigers, swarms of bugs, leeches and mosquitoes, vertical jungles and 150 inches (380 centimeters) of rain in the three month rainy season. Crews worked at night under light provided by diesel fuel burning in sawed off oil barrels. The Ledo Road was nicknamed the “man a mile road” for the frequency in which workers died. Hundreds were killed by disease, accidents and Japanese attacks, mainly from snipers and mortars. More were killed from disease and starvation than from fighting.

Kunming, Lashio, Ledo and Hump Fliers

Kunming in the Yunnan province of southwest China was the main distribution point for supplies arriving from the Burma and Ledo Roads. It was controlled by the Nationalists forces of Chiang kai-shek even after the Japanese claimed Burma in May 1942. In the early stages of the war entire factories were moved to Kunming to keep them out of the hands of the Japanese.

Lashio in Burma was a critical entrepot for the Allies in Southeast Asia. Food, fuel, medicines, and other supplies reached Lashio by railroad from Rangoon and were then carried by truck to Kunming.

Ledo in India was connected to the port of Calcutta by rail. It was the main source of material to China after Lashio and the Burma Road were captured by the Japanese. Ledo was important to the British mainly as a coal source. In the 1870s, a 2.4 billion metric ton coal supply was discovered here and the railroad was built primarily to bring this coal to Calcutta.

After the Burma Road was cut off military cargo was brought into China by "Hump Fliers" who flew through 15,000-foot-high passes in the Himalayas. Planes flying over the "Hump" arrived in Asia from America via South America and Africa. On their missions they departed from India and flew over the mountains on the China-Burma border to Kunming.

About 1,000 planes went down over China during World War II. A total of 607 of them were hump fliers. Others were Flying Tigers who fought for the Nationalists.

Stilwell and Merill's Raiders

Generals Stilwell and Merrill

Stilwell commanded the Allied forces in the China-Burma-India theater and was the first foreign commander to lead regular Chinese troops in combat. His mission was to keep China fighting, drive the Japanese out of Burma and reopen the Burma Road. The Ledo and Burma Roads were sometimes collectively called the Stilwell Road in his honor.

Stilwell was a controversial figure. He described himself as impatient and vulgar. In his diaries he referred to the Japanese as "bow-legged cockroaches," Chiang kai-shek as "ignorant" and "grasping," British supreme allied commander Lord Lois Mountbatten as a "glamour boy," and Roosevelt as a "rank amateur in all military matters" prone to "whims, fancy and sudden childish notions." One of the few people he admired was Mao Zedong

Stilwell had been the unofficial commander of several Chinese divisions that, with British help, defended Burma against Japanese attack. Stilwell, was driven out of Burma in 1943 in a legendary march from Myitkyina after the completion of the Ledo Road to the pipelines from India. But returned two years later to help drive the Japanese out of Burma.

Another important American fighter in the China-Burma theater was Frank Merrill. He headed an American commando unit, known as Merrill's marauders, that landed in China on parachutes and gliders and helped reinforce the Nationalist forces.

Black American Soldiers Build the Stilwell Road

Most of the men ordered to make the Stilwell Road were African American soldiers sorted into Army units by the color of their skin. The Los Angeles Times reported: “As World War II raged, they labored day and night in the jungles of Burma, sometimes halfway up 10,000-foot mountains, drenched by 140 inches of rain in the five-month monsoon season. They spanned raging rivers and pushed through swamps thick with bloodsucking leeches and swarms of biting mites and mosquitoes that spread typhus and malaria. Some died from disease or fell to their deaths when construction equipment slid along soupy mud tracks and dropped off cliffs. Others drowned, or were killed pulling double duty in combat against the Japanese. [Source: Los Angeles Times, December 30, 2008]

Evelio Grillo was one of the African-American that helped build the Stilwell Road. He told the Los Angeles Times he had to suffer the indignities of racial segregation on the 58-day passage to India aboard the Santa Clara, where the only comforts were reserved for the white officers. Grillo remembers most of them as vulgar racists, and wrote in his memoir, "Black Cuban, Black American," that the road builders assumed that the white men giving them orders in Southern drawls had been selected because they were "deemed to know how to handle black men."

The black GIs had to bunk in the ship's windowless, foul-smelling hold, stewing in the "stench cooked up by the sweat, the farts and the vomit of 200 men," he recalled in the memoir. "White troops had fresh water for showering," Grillo continued. "Black troops had to shower with sea water. White troops had the ample stern of the ship to lounge during the day. Black troops were consigned to the narrow bow, so loaded with gear that it was difficult to find comfortable resting places."

Things only went downhill in the jungle. In a letter home, handwritten on Red Cross stationery and dated June 7, 1943, Grillo was looking forward to taking leave in a big city where he could sit on a toilet again. "We'll just have to make the best of whatever comes until such time as this nightmare shall spend itself," he wrote, "and a box of candy or a bunch of flowers shall again be thought of as some of man's most effective and most important 'weapons.' " Grillo fought off malaria 14 times during the war.

The men who built the road weren't honored for their feat until 2004, when the Defense Department marked African American History Month at Florida A&M University. By then, most of the veterans were long dead. The Pentagon could locate only 12 to invite to the ceremony in Tallahassee, and only six were well enough to travel, the American Forces Press Service reported at the time. When Grillo was asked: “Do you think Winston Churchill was right when he said it was a waste of lives building the road?" Grillo closed his eyes and nodded.

Serving in Burma

Albert John Harris wrote in the BBC’s People’s War: “When we flew into Burma I was 21 and our Officer was younger than me, he was just out of Sandhurst. He was what we called a VC man, we wondered where he got his information on Japanese fighter planes! We were flying into Burma in a Dakota with 29 fully equipped soldiers and behind me there were 4 parachutes. We flew at 8000 feet over thick jungle during the monsoon season. The officer told me to put the Bren gun (there were no doors on the plane) towards the open door and lay on the corrugated floor with the muzzle pointing outwards. When I asked the officer what would stop me sliding out---he said 2 other men would hold my ankles! All 3 of us would have gone out the plane if we had done this. The plane was yawing and pitching. I asked the Officer if he had told the pilot because all I would have shot was the tail of the plane. That was my introduction into North Burma. We all felt that life in the war was very cheap. [Source: BBC’s People’s War]

We were under the command of the Americans General “Vinegar Joe” Stilwell and our job was to take over from Merills Ms.. who had captured Mychyna Airfield and reopen the Ledo Road. Originally the Burma Road went up through into Mandalay and supplied China with arms. By occupying Burma they shut the road so the road was reopened further north by the allies. It was a fantastic feat of engineering. We were in Burma for 18 months and all supplies were dropped by parachute the whole time from Dakota planes. The American Dakota planes could accommodate 29 fully armed soldiers, fly on one engine, not fast but reliable. From 1936 for the next 20 years ½ million of these aircraft were built. They were made under licence in Japan. The Japanese called them Topsys. They are still flying somewhere. Fighting in the jungle, there were no front lines, they could get round you and we could get round them. We formed perimeters and waited for their attack. Fighting was mostly at night. The Japanese were masters of camouflage---you could almost walk on them before you realised they were there. It meant that we had to stay in our positions for long periods and could not fire mortars or use the guns.

Our first experience was in the Arakan in 1944. Whatever they did we were never surprised. There was a hill called 551 like a block pyramid---you could not get up to the top except on your hands and knees as it was sheer. They picked this place because it covered a tunnel going through the road to Buithidang and by holding this hill 551, they controlled the road. They could not reinforce it because we were surrounding it . No one really knew how many Japanese were up on top of hill 551. We were there with the largest field gun in Burma, 7.2 inches and the shells weighed 94 lbs. It was like a turkey shoot, the air was so clear you could see 4 ½ miles as the crow flies without your field glasses and they were firing these field guns every day from 9am till 4pm. Our planes (RAF Vengeance Dive Bombers) fired bombs too, 2 x 500 lb bombs strapped to each wing. Eventually the hill was reduced in size by 6 ft! We could not believe that the Japanese were still at the top of hill 551 and it took 2 attempts to capture it. These Japanese troops were crack troops who had captured Singapore---their best troops called the Imperial Guard. In one night 5000 Japanese marched from Buithidang. In 12 hours they marched 30 miles (or more really considering the terrain). All they had was what they carried on their backs and their mules. Their idea was to capture these big guns and go on to India . We were the second lot of troops to relieve battle of the Admin Box---they weren’t. They died of starvation, the Admin troops held their ground. They were supplied by air for 3 weeks. The wounded in the field hospital were bayoneted . In the end no one surrendered to the Japanese. Bodies were left in jungle where they fell. For the Admin Troops of the 7th Indian Division the Battle of the Admin Box in the Arakan Yomas must have been a nightmare. I never saw one Japanese plane, we had air superiority. Japanese supplied by Burmese---plenty of rice around.

“Although I came from London it was amazing how quickly we adapted to the noises, heat, monkeys of the jungle. A panther used to come to our camp every night because we had taken his water hole! He didn’t attack us---there was no chance against a Bren gun! We had boa constrictors, tigers. We were 7000 feet up and had the monsoons---when they started they came across the Bay of Bengal, the cloud was almost at sea level. I reckon we had 200 inches of rain in 2 or 3 months. You could be on dry land and the following morning be in 2 feet of water. It affected the equipment---you filled up your mess tin with food and walked back to your bivvy and the food was swimming in water. Luckily the rain was warm! Temperatures were100 degrees F. We were ready to take Malaya in 1945 (Operation Zipper scheduled for 9 September 1945) when the 2 atom bombs were dropped on Japan. This saved hundreds of thousands of lives because 10,000 Chinese communists in Malaya 1948 held up the British for 2 years. There were 100,000 allied troops and if fighting the Japanese had continued many lives would have been lost.

Long Trek from Burma to China

Describing what he did after he got stranded in Burma after the Japanese captured Mandalay, Ronald Schofield wrote in the BBC’s People’s War: In 1942 I found myself in Burma, in the Shan States. I was 22 years old and had been in the army for a few years already, but it was still a long way from Batley in West Yorkshire where I had been brought up![Source: BBC’s People’s War website]

“I was stuck in the middle of nowhere and had to find somewhere to go before the Japanese came. There were no proper roads. Even now the area is very desolate. A small group of men and I decided that the only way out was to walk out. We had to cross the foothills of the Himalayas, which rise to over 8,000ft. There were many rivers, which ran in steep gorges and were difficult to cross. To cross we had to climb down 2,000ft through very thick jungle. The wide, fast-flowing river at the bottom was made up of 'ice melt' water from the mountains, so it was very cold. Once we had crossed the river, we then had to climb all the way back up to 8,000ft.

“The jungle was so thick that we couldn't walk in a straight line. We often walked five or six miles to climb back up to the top of the gorge, which may only have been three quarters of a mile as the crow flies. On the map it looks as though I walked about 400 miles, but in reality, because of the number of rivers to cross and the difficult terrain, it was much further. When we got to the top of each gorge, we would look back and could see the other side. We had probably only travelled half a mile and it had taken several days.

“ I had a map made of silk, so that it could be stuffed into a pocket. However, only parts of this region were mapped. Most of the map was just white! I still have this map on my wall today. Even a current map of the area describes the roads as very primitive and there are still large areas of the map that are shown as 'Relief Data Incomplete'. The villages were very small and we didn't dare stay in them for health reasons. We always camped a mile or two away, and usually upstream. The villages were always by a mountain stream and the people who lived there drew their water from upstream and used the lower stream as a sewer.

“Our route: On 28 April 1942 we left Kentung in the Shan States in an old lorry, heading north west. Day 4 - Mongnoi, Wa State. On foot with ponies. Day 11 - Crossed Nam Loi River. Originally heading for Lashio but we changed plans here and decided to head for China. Day 12 -Tolou, Wa State. Day 22 - Crossed Nam Lan River. Now in China. Day 27 - Ta Ya Koi, Yunnan Province, three miles from Mekong River. We were warned not to go to crossing point at Sau Mao as it was held by Chinese army deserters and bandits. Camped up river. Day 28 - Crossed Mekong River. The Mekong River is approximately 2,800 miles long. It runs in steep gorges for most of the upper course. Where I crossed the river the gorge was an incredible 8,000 feet deep.

“Day 29 - Crossed Taku River. Camped here. Day 41 - Hsia Pa. Crossed Black River. Day 42 - Tung Kuan. A broad cultivated valley. Day 48 - Yuan Chiang Chou. A walled city approximately 1,600 feet above sea level. Camped here preparing to cross the Red River. The delta of the Red River is in Vietnam. Day 51 - Crossed Red River. Day 56- Hsin-Haing Chou. Also called Ishi or Yu-Hsi. Start of motor road to Kunming. We did the last 80 miles in a battered old lorry! What luxury!

“I got to Kun Ming after 62 days of walking. I am quite a tall man and when I got there I was very, very thin and weighed less than eight stone. We had to eat our ponies on the way to stay alive. In Kun Ming I stayed with the American Volunteer Group (AVG), who were American civilians flying fighter planes and transport planes for China.

Fighting in Burma

Japanese soldiers fighting

Both in the The Allies supplied the Nationalists forces of Chiang kai-shek in Kunming using the Burma Road. In the spring of 1942 the Japanese captured Lashio, during their conquest of Burma, and cut off the Burma Road and severed the Allies overland supply line to China. The worker quoted above said, “The Japanese came up the road from Burma. They asked: “Are you a farmer, a laborer, or a rifleman?” If you said you were a rifleman, as three in my village did, the Japanese shot you.”

During the Burma campaign the Japanese often attacked in the middle of the afternoon because they knew that is when the British took their tea time breaks. The Allies parachuted pigs from planes to fed starving populations. Among the colorful characters who took part in the effort was British Gen. Orde Wingate., the head of the legendary Chindit guerillas. He was given his job after a failed suicide attempt and often conducting meetings in the nude while he scrubbed himself with a brush.

The Japanese suffered in Burma. When food supplies ran short, men subsisted on rats, frogs and boiled grass. In some cases they used gasoline to clean their wounds and keep maggots from eating their flesh. By one estimate more 180,000 Japanese soldiers were killed or died of illness in Burma.

Kachin guerillas that fought for the Allies cut of the ears of the Japanese, which left them terrified that they could not ascend to heaven because their bodies were not intact. For their part the Japanese killed their wounded so they could not be captured and killed Allied soldiers instead of taking them prisoner so they wouldn’t be slowed down.

Describing his experience in Burma in World War II one former Japanese soldier told the Washington Post, "So many friends of mine were killed...I hated war. I didn't like fighting I could not tell the general, but I could tell my friend. He died in Mandalay. He died from cholera and lack of food. He was 27. I will go to Mandalay and pray for him." Another Japanese soldier recalled how when the frogs suddenly stopped croaking it meant that British warplanes would soon pass overhead and drop their payloads.

Ronald Needham wrote in the BBC’s People’s War: "We were in the wilds when we were surrounded. I was going for a shave. There was a hill about 500 to 600 yards away where some men were digging in. I was told they were from the Ox and Bucks (Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire) Regiment. I waved to them and walked on as they waved back. I was part-way through my shave when all hell broke loose. There were bullets everywhere. It was the Japanese on the hill! [Source: BBC’s People’s War]

“I was a Bren gunner and ran back to my post at the edge of some trees. I remember there being a Mahratta unit with us. The attack went on for two hours - bullets all over the place. While we were firing a bloke came crawling through the undergrowth on his stomach. "Just you three?" he asked. We said, "Yes," and he replied, "Right. Breakfast's up!" So we crawled through the wood to a hedge and then ran through an open space to some bushes about 20 yards away. Then we ran to the side of a hill another 20 feet or so away. Round the corner they were cooking breakfast. I remember how strange it seemed to be in the middle of a battle and be called to breakfast. At least we could eat in peace!

“On another occasion I was blown up. I can't remember a thing. I woke up days later being asked for my name by a chap. I was told a shell had landed close by. I wasn't wounded. It just shook my brains apart. I was sent home soon after that."

Allies Retake Burma

Stilwell’s troops invaded Burma from India in October 1943. Around the same time a force of British Chindits known as Wingate's Raiders advanced from the south. The fighting turned in the Allies favor after these veteran jungle fighters defeated the Japanese 15th Army at the battles at Kohima and Imphal

Stilwell’s troops invaded Burma from India in October 1943. Around the same time a force of British Chindits known as Wingate's Raiders advanced from the south. The fighting turned in the Allies favor after these veteran jungle fighters defeated the Japanese 15th Army at the battles at Kohima and Imphal

Stilwell’s forces engaged 3,500 Japanese soldiers defending Myitkyina, a strategic port on the Irrawaddy River. The Battle of Myitkyina was fierce. It lasted for ten weeks from May to August in 1944. Some of the fighting was done by Chinese troops under U.S. command. Before the siege was over and the Allies claimed the Myitkyina on August 3, 1944, a total of 790 Japanese were killed and 1,180 were wounded. The Allies suffered 1,244 dead with and 4,139 wounded.

In September 1944, more than 9,000 Chinese and 2,000 Japanese were killed at a battle in Tengchong, China. Here above the raging Salween River, Chinese tried to reach the top of an imposing, 26-mile-long ridgeline on Songshan (Pine Mountain) after a month-long battle that left 1,300 Chinese and 7,675 Japanese dead. Many died in hand-to-hand combat. Sixty-two pairs of Chinese and Japanese soldiers were found dead in each other’s grasp.

As part of Operation Dracula, British soldiers led by Gen. William Mith moved southward and captured Mandalay and Rangoon. Forces under Britain’s General William Slim recaptured Rangoon after a six month campaign.

The Burma Road opened completely between India and China in January 1945, allowing supplies to more easily be brought into China. On May 8, 1945 Supreme Allied Commander Lord Louis Mountbatten declared the Burma campaign a success even though sporadic fighting continued for several weeks. The victory signaled the collapse of the Japanese effort in Southeast Asia.

Image Sources: National Archives of the United States; Wikimedia Commons; Gensuikan;

Text Sources: National Geographic, Smithsonian magazine, New York Times, Washington Post, Los Angeles Times, Times of London, The Guardian, Yomiuri Shimbun, The New Yorker, Lonely Planet Guides, Time, Newsweek, Reuters, AP, AFP, Wikipedia, BBC, "Eyewitness to History", edited by John Carey ( Avon Books, 1987), Compton’s Encyclopedia, "History of Warfare" by John Keegan, Vintage Books, Eyewitness to History.com, "The Good War An Oral History of World War II" by Studs Terkel, Hamish Hamilton, 1985, BBC’s People’s War website and various books and other publications.

Last updated November 2016